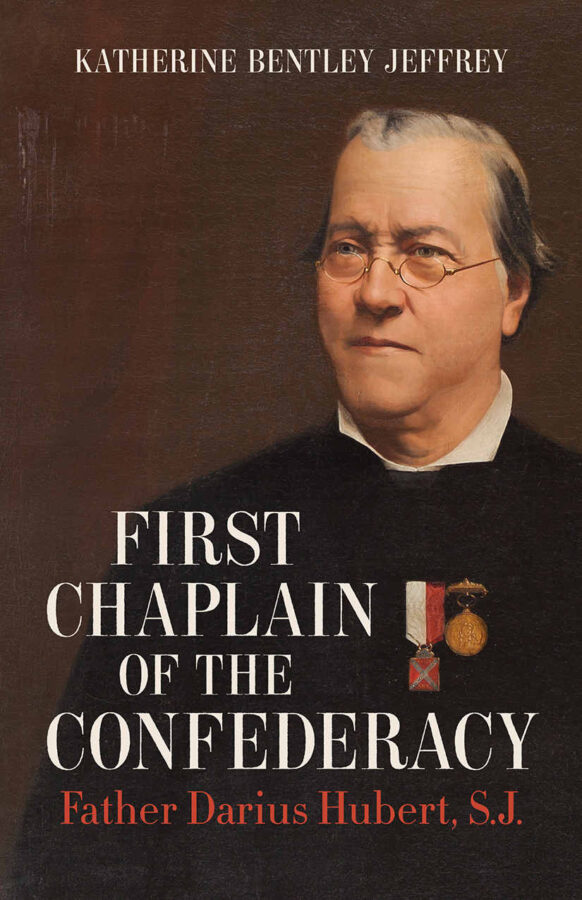

First Chaplain of the Confederacy: Father Darius Hubert, S. J. by Katherine Bentley Jeffrey. Louisiana State University Press, 2020. Cloth, ISBN: 978-0-8071-7337-4. $45.00.

Darius Hubert, a French-born, Louisiana-based Catholic Jesuit, was the “first person appointed as chaplain to any Confederate military unit.” He was attached to the First Louisiana Infantry Regiment in the Army of Northern Virginia throughout the duration of the Civil War (40). Katherine Bentley Jeffrey, an independent scholar, has meticulously resurrected Hubert’s life from historical obscurity. Jeffrey was faced with a “paucity of primary material, especially war correspondence or papers related to his lengthy pastoral tenure in New Orleans” (xiii). Yet despite these difficulties, Jeffrey succeeds admirably in telling Father Hubert’s story.

Darius Hubert, a French-born, Louisiana-based Catholic Jesuit, was the “first person appointed as chaplain to any Confederate military unit.” He was attached to the First Louisiana Infantry Regiment in the Army of Northern Virginia throughout the duration of the Civil War (40). Katherine Bentley Jeffrey, an independent scholar, has meticulously resurrected Hubert’s life from historical obscurity. Jeffrey was faced with a “paucity of primary material, especially war correspondence or papers related to his lengthy pastoral tenure in New Orleans” (xiii). Yet despite these difficulties, Jeffrey succeeds admirably in telling Father Hubert’s story.

Darius Hubert was born in Toulon, France, in 1823. He entered the Toulouse Jesuit novitiate in September 1843 and volunteered for the North American mission in 1848 (6-11). He arrived in Grand Coteau, Louisiana, where he first encountered African enslavement. He did not record his thoughts on the subject, but his involvement with the Confederate cause during the Civil War “would seem to suggest a largely benign and paternalistic view of slavery” (14).

Jeffrey’s biography addresses the local politics and religious landscape of nineteenth-century New Orleans. The work of Hubert brings into focus the immense power of local events and politics in the lives of common Americans during the period. His work with the First Louisiana Infantry Regiment in the Army of Northern Virginia was remembered in highly laudatory terms. The wartime ministry of Father Hubert was characterized by bravery and care for the ill and dying. The Catholic priest, “could not easily be pried away from his men, whatever their creed…nor would he leave them once the guns finally quieted in the spring of 1865” (69). After the war, as he was aging and becoming ill, he offered to resign his position, but “the veterans refused him gently but firmly and continued to list him on all programs until his death as ‘Chaplain to the Army of Northern Virginia’” (137).

Amidst the post-war racial violence that wracked New Orleans, Father Hubert “showed no tendency to ‘stand by’ one race over another” (110). He had instructed and catechized Black and white children, just as he had interacted with people of color throughout most of his adult ministry. Therefore, the author argues, he was able to focus on the “obligations of practical charity, and spiritual rather than political reconstruction” (111).

Still, in New Orleans, Father Hubert appears to have been one of the “spiritual” fathers of the Lost Cause. Jeffrey calls him “intercessor-in-chief,” as Hubert was invited to pray at various political and remembrance events (125). His prayers were “repeated for decades afterward” (124). Though he christened many Lost Cause statues and memorials, there were none erected in honor of Father Hubert. “Failure to bring the old priest home or to establish a tangible memorial to him in New Orleans hastened the time in which his name and legacy would fade from public memory” (145).

With this new biography, Jeffrey hopes her subject “has a modest monument at last” (xix). Though much of Hubert’s life is obscured by “holes” in the preserved, historical record, Jeffrey’s biography reminds us of the nuanced role Catholics played in the Confederate and Reconstruction South.

Caleb W. Southern is an MA candidate in the Department of History at Sam Houston State University.