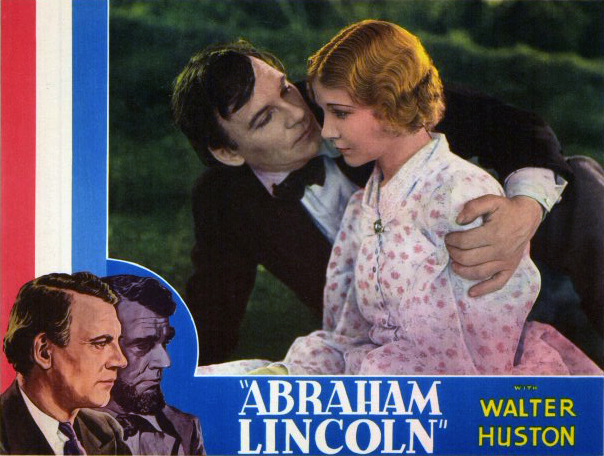

The infamous director’s 1930 biography of Lincoln was one of only two “talkies” made by Griffith, and stars Walter Huston in the title role. The screenplay is by Stephen Vincent Benét, who the year previous had won the Pulitzer Prize for his book-length poem, John Brown’s Body. The film is the earliest feature-length film on Lincoln.

As history, it’s a sloptastic mess. Here, secession features prominently in the Lincoln’s famous debates with Stephen Douglas, and near the end of the film, Huston gives a monologue just before being assassinated that’s a mishmash of lines from the Gettysburg Address and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural. Ann Rutledge wears her hair in a 1920s Marcel wave. In what may be an editing sequence error, Virginians react to the news of John Brown’s raid after Lincoln is approached to be a candidate for president on the Republican ticket. Winfield Scott is depicted as an overconfident fool, when in fact he was one of the few who saw early on the horrific cost the war would eventually claim. The assassination scene is almost comical, with Mary Lincoln seemingly unaware that anything had occurred, until someone in the audience shouts that the president had been shot. And oddly, it seems, the film closes with shots of models of both the Lincoln Memorial in Washington and Daniel Chester French’s famous statue within, rather than footage of the actual location.

As history, it’s a sloptastic mess. Here, secession features prominently in the Lincoln’s famous debates with Stephen Douglas, and near the end of the film, Huston gives a monologue just before being assassinated that’s a mishmash of lines from the Gettysburg Address and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural. Ann Rutledge wears her hair in a 1920s Marcel wave. In what may be an editing sequence error, Virginians react to the news of John Brown’s raid after Lincoln is approached to be a candidate for president on the Republican ticket. Winfield Scott is depicted as an overconfident fool, when in fact he was one of the few who saw early on the horrific cost the war would eventually claim. The assassination scene is almost comical, with Mary Lincoln seemingly unaware that anything had occurred, until someone in the audience shouts that the president had been shot. And oddly, it seems, the film closes with shots of models of both the Lincoln Memorial in Washington and Daniel Chester French’s famous statue within, rather than footage of the actual location.

And of course, being a D. W. Griffith production, it includes at least one white actor in blackface, in the Harper’s Ferry scene. (At about 33:40, if you want to skip it.)

But it also captures on film much of what we now expect to see in depictions of Lincoln on film — the bouts of depression, the folksy charm, and the keen politician hidden just beneath the veneer of a backwoods country lawyer. Huston brought to the screen, for the first time, many of the familiar elements of Lincoln that most Americans now take for granted.

I sometimes like to point out to friends that, when they see an actor playing Mark Twain on stage or screen, what they’re usually seeing is an actor playing Hal Holbrook playing Mark Twain, because Holbrook has, over the last five decades, completely shaped Twain’s persona in the public’s mind. (Wiki quips, “[Holbrook] has portrayed Twain longer than Samuel Langhorne Clemens did.”)

So here’s my question: how has Walter Huston’s performance 80 years ago shaped later actors’ portrayal of Lincoln? What do you see in this film, that would come to be repeated again and again? Should Spielberg be taking notes from this picture?

Andy Hall is a Texan and Southerner by birth, residence and lineage, with a family tree full of butternuts. With a background in history, museum studies and marine archaeology, Hall also writes at his own blog, Dead Confederates.