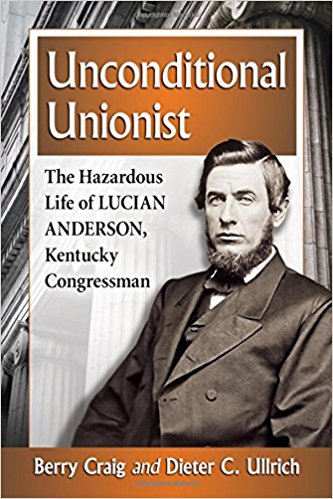

Unconditional Unionist: The Hazardous Life of Lucian Anderson, Kentucky Congressman by Berry Craig and Deiter C. Ullrich. McFarland & Company, Inc., 2016. Paper, ISBN: 978-1476663692. $35.00.

Kentucky is the sphinx on the landscape of the American Civil War, and those of us enamored of the riddle of Kentucky’s wartime loyalty and regional identity have no greater quandary to unpack than Lucian Anderson. The Congressman hailed from the heart of rebellion in the state—Mayfield—site of the regional secession convention that was the prelude to the formation of the provisional Confederate government.

Kentucky is the sphinx on the landscape of the American Civil War, and those of us enamored of the riddle of Kentucky’s wartime loyalty and regional identity have no greater quandary to unpack than Lucian Anderson. The Congressman hailed from the heart of rebellion in the state—Mayfield—site of the regional secession convention that was the prelude to the formation of the provisional Confederate government.

It would follow that a Unionist hailing from such a place might align himself with the most conservative elements of loyal Kentucky, those whose condemnations of rebel treason were matched only by their grumblings about Lincoln’s interpretations of the Constitution. Yet Lucian Anderson, antebellum Democrat, supported the Republicans’ prosecution of a hard war against his treasonous neighbors. Lucian Anderson, slaveholder, voted for the Thirteenth Amendment. Unlike his now more famous colleague George H. Yeaman (of Spielberg’s Lincoln fame), Anderson was not rewarded for his vote with a diplomatic post that removed him permanently from the reach of his angry constituents. Lucian Anderson—the embodiment of the unconditionally patriotic southern man that Abraham Lincoln prayed could overlook individual and regional interest to preserve the nation—lived his war and his long life afterwards at home, among his conservative friends and neighbors in the heart of Kentucky rebeldom.

The book is subtitled appropriately. Anderson lived a hazardous life indeed. Craig and Ullrich illuminate the shocking fact that Anderson was kidnapped and held by rebel guerrillas just before he assumed office. Think of the chaos of this Civil War era (and the preoccupation of us, its students, with battlefield glories) that a United States Congressman-elect was captured and nearly killed by armed enemies of the state, and hardly a soul who studies the war is aware of the fact today.

Why has Anderson gone so long unnoticed? The authors’ conclusion to a story of 1861 election violence in Mayfield says it all. “Anderson evidently escaped physical harm, though one must wonder how much derision he had to endure. Because there is no record, we can only guess at the fate of an outspoken Union man in a rabidly rebel town.” Lucian Anderson poses some of the most natural questions about communities torn by civil war—questions still relevant to global conflicts and a stark domestic political divide today. “Was he cursed and reviled as he walked the streets? Or was he such an affable fellow that most people looked past his ‘sins’[?]” (62).

As they underscore in that passage, Anderson left no papers, leaving this writing team—a university archivist and a respected historian of Anderson’s Jackson Purchase region—creatively filling in footnotes from scattered correspondence, official records both congressional and military, and newspapers. These limitations are lamentable but still frustrating. The partisan Kentucky press, led by the increasingly spiteful George Prentice of the Louisville Journal, did Anderson’s reputation no favors in 1864 and 1865, leaving the reader begging for some of Anderson’s words to reply in kind.

Compensating for a lack of Anderson, Craig and Ullrich sketch a memorable cast of Unionist characters in rebel Graves County. Some, like resourceful Judge Rufus Williams, manage to leverage their unionism to get safely out. Others were pitilessly murdered for their convictions, a fate that Anderson only too narrowly avoided. The chorus is useful at times to show us the shades of loyalty that constituted the spectrum of Unionism in Kentucky, but readers not already familiar with the rough and tumble of Western Kentucky politics might lose Anderson as the supporting cast moves on and off the stage.

Anderson’s biographers close the story quickly after the war ends, though Anderson was active for decades in the beleaguered Kentucky Republican Party. Anderson stayed out of office and largely out of the public eye—and, therefore, out of the documentary record. All the questions that lingered over that 1861 episode linger still. Do not mistake: Craig and Ullrich have done students of Kentucky’s Civil War a service. They have worked hard to raise questions about the depth of loyal sentiment in a region supposed to be the citadel of treason in the state. They have ensured that future statewide narratives cannot overlook the Purchase, and have plainly made the case for further biographies of Kentucky political leaders. Even if they are subjects as archivally challenging as Anderson proved to be, historians need to better understand the local context for stances on secession, emancipation, and war policy if we ever hope to answer the riddle of the Kentucky sphinx.

Patrick Lewis is Director of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Project at the Kentucky Historical Society.