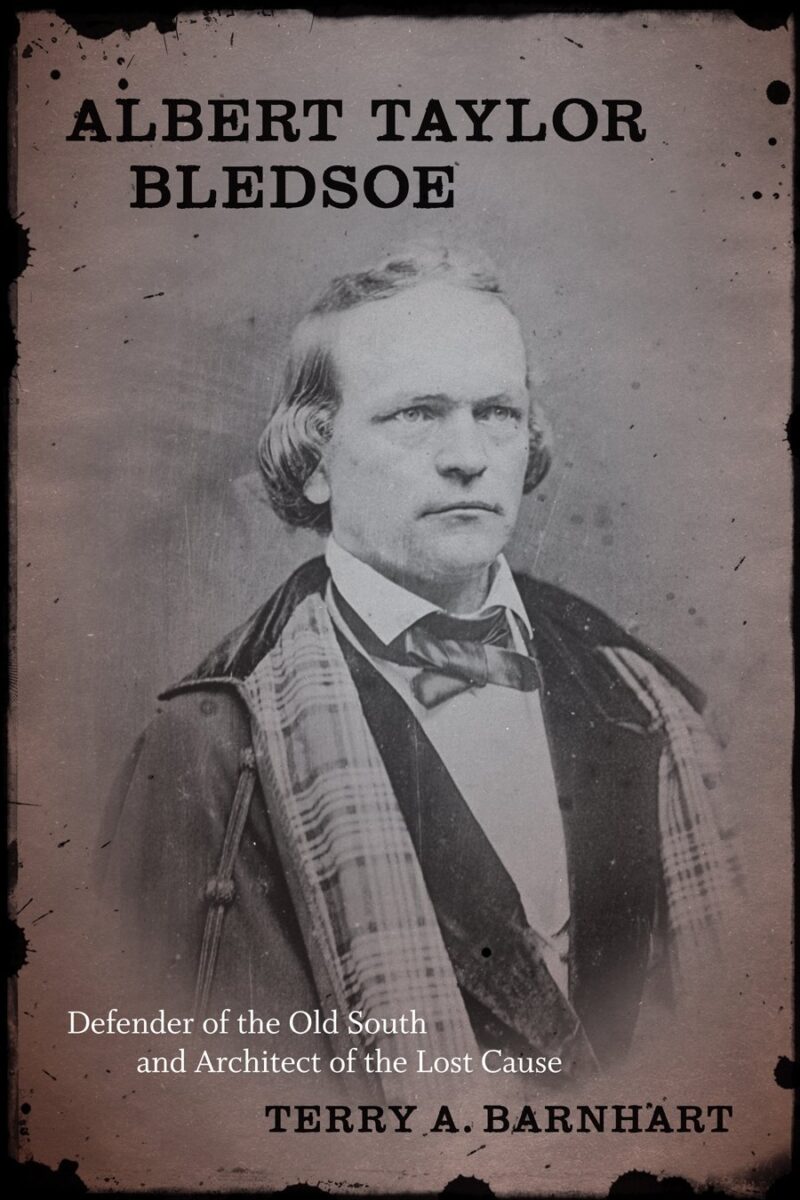

Terry Barnhart’s intriguing biography of Albert Taylor Bledsoe reveals that Bledsoe, like the Old South he cherished, was a paradox. Long recognized as one of the most respected—and most unrepentant—southern intellectuals of the nineteenth century, Bledsoe’s writing was and continues to be well-known. Although his prolific writing career made him a public figure Bledsoe himself remains a bit of a shadow—as Barnhart admits, little of his personal correspondence, papers, and manuscripts survive today. Despite the limited material available, Barnhart has made a worthy and instructive effort to explore the significance of the man who became “the architect of the Confederate interpretation of the conflict” (6).

Barnhart’s primary purpose in this work is to put Bledsoe’s writings in their proper context, and to that end he provides an engaging overview of a man whose life reflects the curiosities we have come to expect in the Civil War generation. Born in Kentucky and educated at West Point, Bledsoe lived much of his life in the North, even befriending his fellow Illinois lawyer and Whig supporter, Abraham Lincoln. But after 1848, when Bledsoe joined the faculty of the brand new University of Mississippi, his loyalties evolved. Along with cultivating an enduring friendship with Jefferson Davis, Bledsoe became a pro-slavery apologist, staunch defender of secession, and one of the formative influences on the post-war Lost Cause. Teasing out how this evolution occurred, Barnhart deftly, if unevenly at times, traces Bledsoe’s strange career. Although the author is careful to identify Bledsoe’s intellectual peculiarities and inconsistencies, particularly on the subject of race, he does so in moderation. The result is a tone of persistent admiration for Bledsoe that permeates, but does not dominate the book.

Bledsoe was a talented mathematician and a rigid logician, and he used these skills throughout his life to be a “controversialist” above all else (4). The pursuit of controversy comes at steep cost, however, and the real insight of Barnhart’s work is that it shows that while the courage of our convictions may animate us, they also contain the power to destroy. A man of faith, Bledsoe drifted from denomination to denomination. An esteemed professor, Bledsoe demonstrated a fragile pride, frequently changing jobs and arguing with colleagues. A famous author, Bledsoe’s insecurities manifested themselves in heated exchanges with his critics. Due to the fragmentary nature of the source material on Bledsoe, we will probably never know in more detail the origins of his restless personality, but it is fascinating that a man so central to the arguments of the Civil War era would so clearly be eternally at war with himself as well as with the changing ideas of the times in which he lived.

Given the somewhat mysterious personal background of his subject, it is appropriate that Barnhart chooses to focus on analyzing the significance of Bledsoe’s numerous publications. Barnhart is obviously not the first historian to comment on the impact of Liberty and Slavery (1856), or Is Davis a Traitor (1866), among many other works, or to point out the influence of the Southern Review, which Bledsoe edited from 1867 to 1877. But since Bledsoe wrote about such a variety of subjects, including mathematics and theology as well as slavery and the Civil War, it is helpful to identify, as Barnhart does throughout the book, how Bledsoe’s dogged attachment to the logic and precision of mathematics infused his passion for political and theological arguments as well. Taking the long view of Bledsoe’s work does shed light on how a former Whig could be transformed into a states’ rights secessionist and offers a valuable perspective on how Bledsoe and his contemporaries found themselves enveloped in the controversy that caused the Civil War.

There are occasional holes in Barnhart’s analysis—for example, he is mostly content to discuss Bledsoe’s frustrations as editor of the Southern Review rather than take the opportunity to explore how Bledsoe helped define the nascent Lost Cause mythology that would prove so enduring for white southerners. But such omissions aside, Barnhart deserves praise for presenting a balanced and nuanced portrayal of a man whose ideas have long been justifiably discredited. Despite being defeated in the end, it turns out that the fight Bledsoe waged to vindicate the Confederacy remains relevant. Part of our continued obsession with the Civil War and the Confederate cause comes from the recognition that while one cannot condone the twisted, racist dogma that endorsed the institution of slavery, there is at least a logical—one might say mathematical—proof that could be made (and of course, was) for the right of secession. No one argued that right with more precision and passion than Albert Taylor Bledsoe.

Benjamin Cloyd is an Instructor of History at Hinds Community College and the author of Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory (2010).