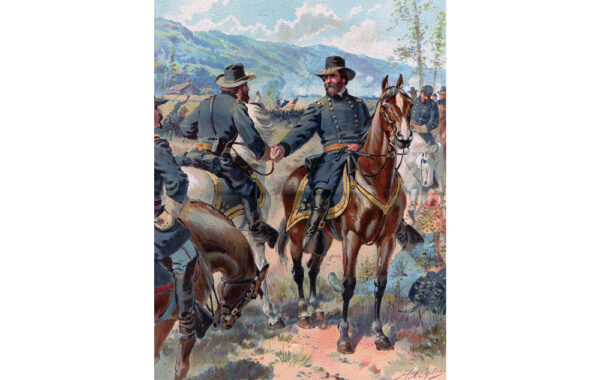

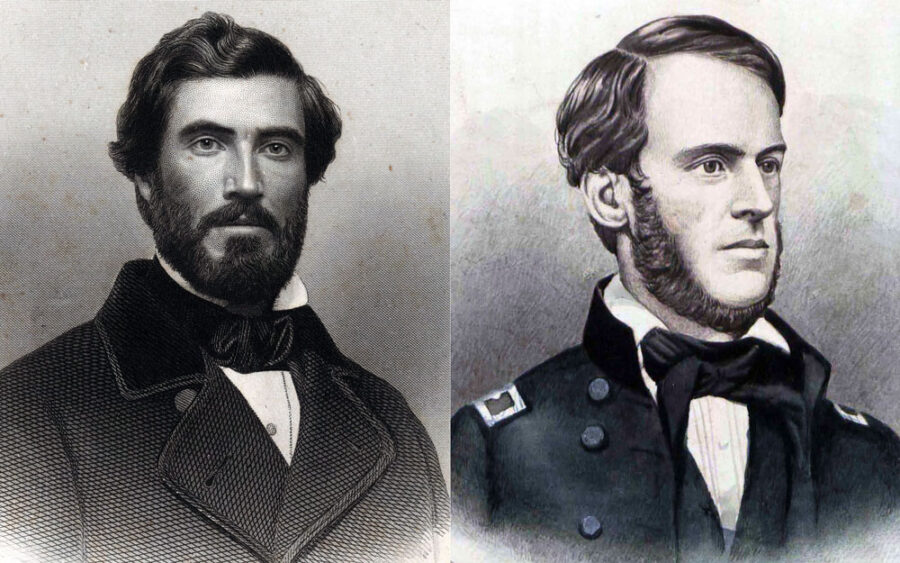

National Portrait Gallery; Library of Congress (right)

National Portrait Gallery; Library of Congress (right)Wartime images of Union General William T. Sherman (left) and his younger brother U.S. Senator John Sherman.

One day in late August 1862, John Sherman, a freshman U.S. Senator from Ohio, wrote his older brother Major General William Tecumseh Sherman with important news from the nation’s capital: “You can form no conception at the change of opinion here as to the Negro Question,” he wrote, meaning the issue of emancipation. As John explained, the necessity of emancipation as a war measure was now widely accepted by northern men of both major political parties, making a drastic change in federal emancipation policy no longer a matter of if, but rather when and how.1

William received the news while serving as the military governor of Memphis, Tennessee. That his younger brother had written was no surprise; they had remained family even when death and distance had separated them as boys. John was 6 and William 9 when their father, a justice on the Ohio Supreme Court, died in 1829, leaving them, their mother, and their nine siblings with no inheritance. William was fostered out and John was kept home. The brothers began corresponding in the 1830s and would continue for 50 years, well into their old age. By then, William had retired as the overall head of the U.S. Army, and John was serving out the last of his 30-plus years in the U.S. government, a tenure that included two cabinet positions and more than one aborted attempt at winning a presidential nomination.

Yet the Civil War was the central event of the brothers’ lives. William would rise from obscurity during the war before claiming fame and suffering infamy as the man who burned Atlanta and conquered the South. John, a successful lawyer in Cleveland, would run for Congress on the winds of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 and never look back. He entered the Senate in 1861 and became one of the war’s most important legislators. Through it all, their relationship remained as strong as ever. Letters flowed back and forth from D.C. to the front, one proof that, for the Shermans, the American Civil War was truly a “brothers’ war”—not because they fought each other, but because they fought together.

But John knew to broach this issue with caution. Emancipation represented the one subject on which the brothers could never agree: John, like most Republicans, came to see it as essential to the war effort; William believed it only deflected attention away from the primary goal of winning the war and restoring the Union. This conflict persisted even after the war evolved in a way that made emancipation its defining issue.

We can only imagine how John might have winced, preparing for the blowback when he told William that he was now ready to “meet the broad issue of universal emancipation.”2

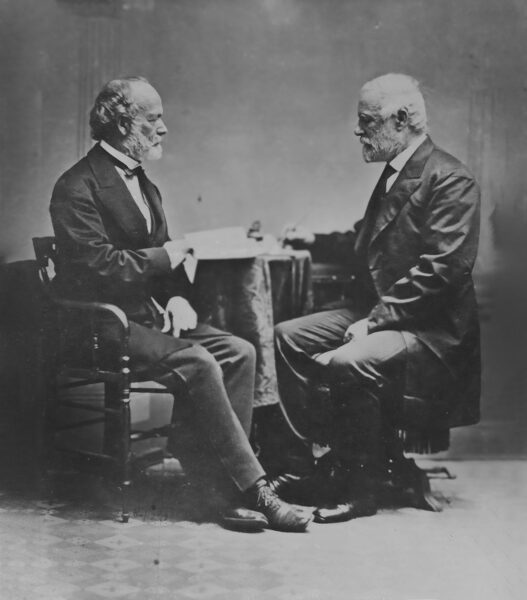

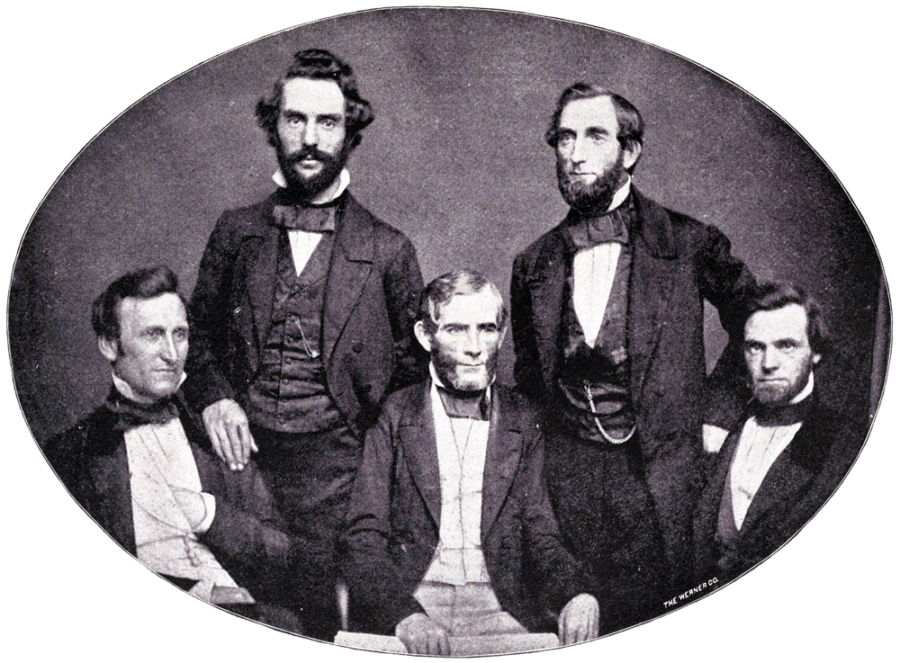

"Recollections of Forty Years in the House, Senate, and Cabinet" (1896); Library of Congress (Sherman house)

"Recollections of Forty Years in the House, Senate, and Cabinet" (1896); Library of Congress (Sherman house)After their father died in 1829, John Sherman (shown above left at age 19) remained in the Lancaster, Ohio, family home (shown here in a 20th century photo), while William was fostered out to a friend’s family. The brothers soon began a correspondence that would continue for 50 years.

Neither brother knew much of slavery in their youth in eastern Ohio. Back in the 1780s, when Ohio was little more than an unsurveyed expanse on the nation’s western frontier, the Confederation Congress, the predecessor to the first national congress, issued an edict known as the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. The ordinance created the “Northwest Territory,” which was soon divided into the states of the modern Midwest: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and parts of what is now Minnesota.

Though primarily a land scheme, the Northwest Ordinance contained a critical provision outlawing slavery and involuntary servitude, which is why those states remained free of slavery, even as neighboring states like Kentucky or Missouri allowed it. Later, in the years before the Civil War, when slavery’s status in the American West emerged as a crucial issue, radical antislavery forces would once again turn to the Northwest Ordinance and its antislavery provision, arguing that it represented the true vision of the Founding Fathers when it came to settling western lands. So, the Ohio these Sherman brothers were born into—in 1820 and 1823—was an Ohio free of slavery.

As teenagers, the brothers’ paths diverged again. William entered West Point at 16, and after graduating, his early army career took him to postings across the South. It was in these places that he saw slavery for the first time and began to form his own views of the institution, which, as many biographers have noted, were not all that different from those of most southerners. For instance, he believed the value of enslaved labor was far too essential to the southern economy to ever give up. He also considered the American slave system mild compared with other systems in the history of the world. He once wrote John saying that it would be a “folly to liberate or materially modify the condition” of enslaved people in America. These and other such statements show that when William spoke about slavery he did so with a southern accent.3

John, meanwhile, stayed in Ohio, eventually studying the law. His expanding world as a young man was one in which slavery was becoming increasingly unpopular. Not only was Ohio a free state, it was one of the early cradles of abolitionism. The state’s “Western Reserve”—the northeastern corner of Ohio, which originally belonged to Connecticut—had been both a thoroughfare and a landing spot for New Englanders traveling west, making it a little New England west of the Alleghenies. For this reason, northeastern Ohio was about as welcoming of abolitionism as any place in the country. John’s eventual hometown, Mansfield, lay on the Western Reserve’s edge, about equidistant from Columbus and Cleveland.

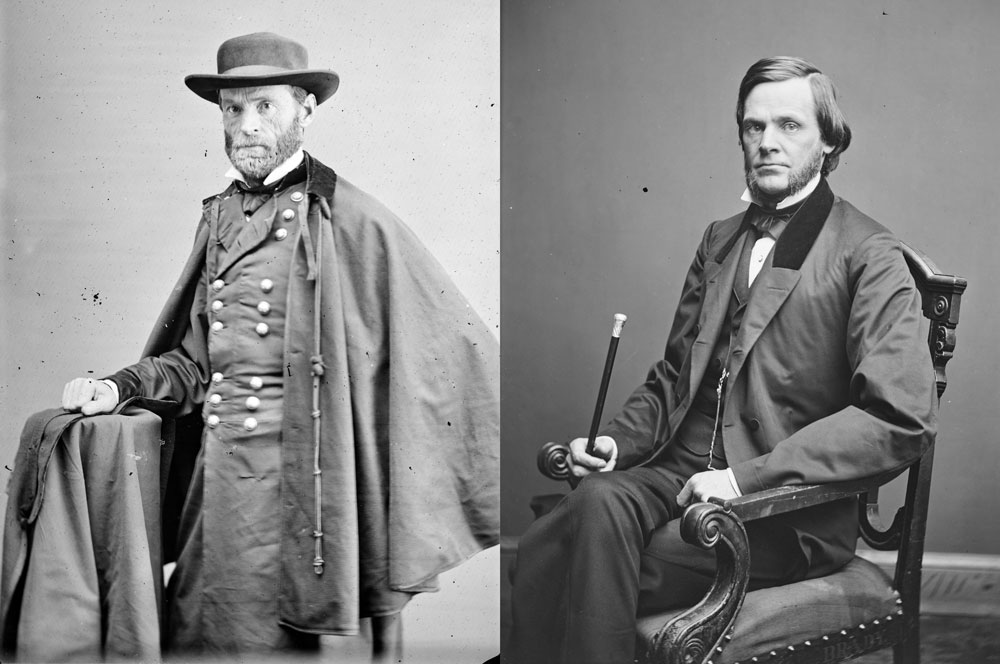

"Recollections of Forty Years in the House, Senate, and Cabinet" (1896); North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library.

"Recollections of Forty Years in the House, Senate, and Cabinet" (1896); North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library.Though he didn’t consider himself an abolitionist, John Sherman’s move into politics was spurred by passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which threatened an expansion of slavery into the West. John Sherman (far right) sits beside fellow congressmen in an 1856 photo.

In short, where William spent some formative years in places where antislavery sentiment was tantamount to heresy, John spent his in an environment where it had cultural purchase. Yet John was never an abolitionist. Instead, he considered himself a moderate Republican. He opposed slavery’s expansion, not necessarily its existence, recognizing, like most Republicans, that there was little Congress could do about it in places where it existed. The issue that brought him into politics was the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which threatened an expansion of slavery into the West. Opposing any such expansion formed one of John’s first principles in politics, but as a candidate for Congress, that was as far as he would go. In his initial campaign, he ran on restoring the Missouri Compromise, which banned slavery in the lands north of the parallel that marked (slave state) Missouri’s southern border.

Evidence of how far the brothers would drift on the issue showed up in the waning days of 1859. William was hired that year as superintendent of a new state military college in Alexandria, Louisiana, a predecessor to today’s Louisiana State University. The position was a lifeline for William, who had struggled in civilian life after resigning his army commission in 1853.

But John’s status as a rising Republican in Congress put something of a target on William’s back, threatening to end his tenure in Louisiana. The higher John rose in the party and the more outspoken he became in his antislavery views, the bigger the bull’s-eye on William for his association with a prominent antislavery Republican. “John’s position [on slavery] may at times force me to appear opposed to extreme Southern views, or they may attempt to extract from me promises I will not give,” William wrote in late 1859 to his wife, Ellen, acknowledging the delicacy of his situation.4

In short, where William spent some formative years in places where antislavery sentiment was tantamount to heresy, John spent his in an environment where it had cultural purchase.

The popular reprinting of Hinton Rowan Helper’s 1857 book, The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It, a sociological study of the country’s slaveholding region, wound up affecting John in his free state more than William in his slave state. Helper, a child of the North Carolina piedmont who was both a fierce antislavery advocate and white supremacist, offered a scorching assessment of the South’s future that targeted slavery as the source of its ills. He argued that slavery effectively stunted southern growth, fostering not just a retrograde economy, but a stifled and regressive culture. Even more, he concluded that the North, so long as it continued to diversify and industrialize, would continue to lead the nation in the arts, culture, and literacy while the South remained a cesspool of ignorance and degradation. Helper’s solution to the crisis: class war. He encouraged the poor farmers of the South to rise up and eliminate slavery as a system, extinguish slaveholders as a class, and remake the South by toppling the plantation system. After their emancipation, blacks, whom Helper considered an inferior race, were to be removed from the country.

Helper’s book, condensed and republished in 1859, raised a riot in the South, becoming the nonfiction equivalent to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The already awkward situation for William in Louisiana suddenly became worse, however, when copies of The Impending Crisis of the South began circulating with an endorsement from John. The younger Sherman, along with several other Republicans in Congress, had signed copies of the book with plans to distribute it throughout competitive states in advance of the coming presidential election. It was a clever political ploy, but now John had been outed and cast as the ringleader of the whole affair. The vehement reaction from aggrieved southerners in the House resulted in their scuttling John’s bid for the Speaker’s gavel.

Yet while John paid a price politically, it was William in Louisiana who feared worse. He had worked hard to shore up his status in Louisiana, but his brother’s endorsement of such a controversial book made his situation as tenuous as ever. He immediately wrote John, who responded by repudiating Helper’s claims and disavowing his role in the controversy. John claimed to have never read the book, much less consented to having his signature on it, which was little more than a classic political disclaimer. But John’s repudiation of the book was all the cover William needed. He circulated John’s disavowal among members of the Louisiana Legislature, which eased the tension, but William’s worries remained.

“What I apprehend is because John has taken such strong ground on the question of slavery, that I will first be watched and suspected, then may be addressed officially to know my opinion, and lastly some fool in the Legislature will denounce me as an abolitionist spy,” he told his wife.5

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Helper), USAHEC (Sherman)

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Helper), USAHEC (Sherman)Portraits of Hinton Rowan Helper (left) and William T. Sherman

The Helper controversy revealed to each brother where he stood on the issue cleaving the country. For William, the threat of a crisis forced to him consider just how far he would go to remain in Louisiana. He wouldn’t fight against Ohio, and he abhorred the idea of secession, considering it plainly illegal and unpatriotic. Yet he laid blame for the political tension not with southerners, but with northerners, especially those pesky abolitionists, for essentially provoking the slaveholding South. He made it clear that he would not fight a war in the name of abolitionism or support an abolitionist government.

“If they [southerners] design to protect themselves against negroes, or abolitionists, I will help,” he wrote his wife in October 1859, adding the qualifier that “if they propose to leave the Union on account of the supposed fact that the northern people are all abolitionists … then I will stand by Ohio and the North West.”6

John moved in the other direction. Though he disavowed The Impending Crisis, saying that its “ultra” sentiments offended him, the scandal nevertheless shows how combative John had become in his antislavery views. He still considered himself a moderate, and he would pursue sectional compromise right up until the eve of the war. Yet he yielded not an inch on barring slavery’s expansion into the West and had grown more comfortable speaking of an aroused “anti-slavery feeling” in the North that just might make “war against slavery everywhere.” The implication: While he still wanted a restoration of the old Missouri Compromise line, he was open to the overall destruction of slavery—even if it meant breaking precedent or using federal power to do so.7

William resigned his military college position in late January 1861, well after the Helper controversy had faded. As he saw it, he had no choice. South Carolina had seceded from the Union the previous month. It was only a matter of time before Louisiana did the same. The state’s governor, Thomas O. Moore, whom William knew and liked, had already ordered the seizure of the federal military arsenal at Baton Rouge—a hostile action William considered an open act of war. He would resign about one week later, though he remained in Louisiana for another month arranging his and the college’s affairs. He regretted having to leave, but he also knew it was time. War was now practically inevitable.

Once William informed his brother of his plan to resign, John began trying to find him work with the federal government. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase—a fellow Ohioan, whose old Senate seat John would fill later that spring—promised William a job. He had options in the War Department as well. But John cautioned his brother against accepting anything too quickly, knowing that William would likely receive a battlefield commission should he wait. William delayed joining the army, although this didn’t stop him from playing parlor-room general. With his knowledge of military strategy and familiarity with the South, William spent the spring of 1861 writing to John about the war and how he envisioned it playing out.

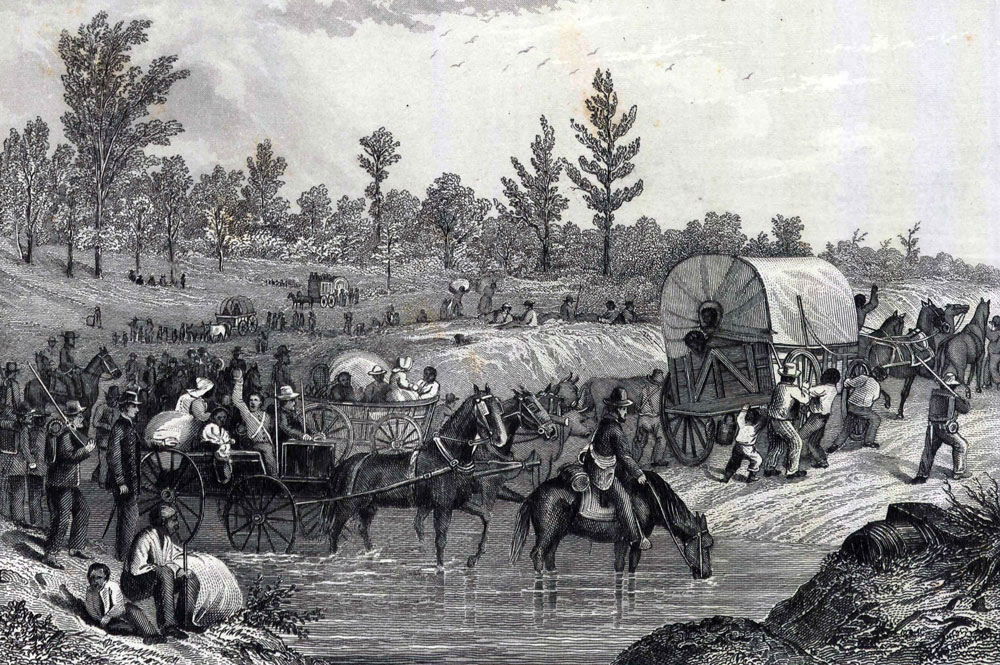

Library of Congress

Library of CongressWell before the first major land battle at Bull Run, William Sherman suspected the war would be anything but civil, describing the coming conflict as one of complete devastation in which formal military bodies would give way to a guerrilla or paramilitary struggle—which it did in the war’s western theater, as depicted above in an 1862 illustration by Thomas Nast.

Even in these early days, well before the first major land battle at Bull Run, William suspected this “civil war” would be anything but civil. Indeed, at a time when Americans of both sections believed the war could be contained or that one battle would decide the issue entirely, William suspected otherwise. He began describing the coming conflict as one of complete devastation, of one side annihilating the other. He fully expected that formal military bodies would give way to a guerrilla or paramilitary struggle, leading to a slaughter of American lives, civilians as well as soldiers. And he would soon come to believe that the only way to reform the South was to strip Confederates of their land and repopulate the region with loyal citizens from the North. As he told his brother in May 1861, “The greatest difficulty in the problem now before the country is not to conquer but so conquer as to impress upon the real men of the South a respect for their conquerors.”8

Long before he implemented his famous “hard war” tactics on the battlefield, William foresaw the inevitability of the war becoming all-encompassing. His early letters to John reveal an anxious pessimism that enough wasn’t being done to prepare for a conflict of this magnitude, and he entreated John or whoever would listen about the need to preempt this totalizing turn. Yet military emancipation remained a bridge too far. William maintained that interfering with slavery would only make a volatile situation worse. As he told John barely a week after the firing on Fort Sumter, “The question of the national integrity and slavery should be kept distinct, for otherwise it will be a war of extermination—a war without end.”9

By early 1862, however, John had begun to view things differently. Prompted by the large numbers of enslaved people who fled to Union army lines in the war’s early campaigns, he began to see emancipation as an integral piece of the war effort: “Seizure of the property of your enemy is justified by the same law that authorizes you to seize his person or destroy his life,” he explained in April 1862 to peers who questioned the constitutionality of wartime emancipation. “War is a horrible remedy,” he said on the floor of the Senate, “but when we are compelled to resort to it, we should make our enemies feel its severity as well as ourselves,” a sentiment eerily similar to statements his brother would become famous for later in the war.10

John backed up these statements in the summer of 1862 by supporting the Second Confiscation Act—an important piece of wartime legislation that acted as Congress’ official endorsement of military emancipation. But a sign of just how far John’s thinking had evolved showed in his support for abolishing slavery in the capital. Ending slavery in Washington, D.C., had long been a battleground issue for the antislavery movement and not just for symbolic purposes. Abolitionists and other antislavery advocates maintained as a legal truism that the federal government possessed the explicit right to legislate on slavery in places where it wasn’t protected by state law—or in places such as federal territories where the U.S. government existed as a lone sovereign. This claim was the key to an entire theory for how slavery could be constrained and placed on what abolitionists described as a path of ultimate extinction.

Of course, southerners disagreed, arguing that, as a property right, the U.S. government had no basis to interfere with slavery at all. Nevertheless, as a federal district, Washington became a test case for the antislavery movement, an example that would either make or break the entire antislavery strategy. Even more, should Congress assert this right, it would set a precedent for abolishing slavery elsewhere, making Washington a bellwether for abolition as a whole.

John recognized this dynamic and became an advocate for taking this extraordinary step. As he saw it, it boiled down to a simple calculation: If not now, when? “We are in the majority in this body. We are in the majority in the House. We have a Republican administration. If we do not show the people of the United States that we have a definite policy, and have the manhood to stand by it, and the intelligence enough to administer it, [then] we ought to be overthrown,” he would say when debating the issue in the Senate.11

John also knew that in advocating for this step he and the Congress ventured into uncharted waters. It was one thing to emancipate enslaved people in a state that was in open rebellion; it was quite another thing to abolish the institution of slavery as a whole. Military emancipation had occurred in wars throughout history and was supported by legal precedent. Outright abolition had far fewer precedents and remained legally questionable. Moreover, in passing the D.C. abolition bill, as Congress did later that summer, John knew the body did more than pursue a pragmatic policy, it levied a political judgment foreshadowing slavery’s demise. When he wrote his memoirs, John spent more time discussing the abolition of slavery in the capital than any other emancipation-related issue.

John’s evolution placed him on a collision course with his brother. Their conflicting views on slavery came to a head later in the summer of 1862. By this time, William had enlisted in the army and assumed the position of military governor of occupied Memphis. The older Sherman still held his previous position, arguing that emancipation was neither a priority nor a necessity. With the Second Confiscation Act on the books, Union commanders now had a mandate from Congress not to turn away enslaved people who fled to their lines. William relished responding to southern slaveholders who wrote asking him to return people who had escaped to Memphis for refuge.

At the same time, William employed a narrow reading of the law’s specifics. Part of what made the Confiscation Act so consequential was that it mandated that enslaved people who arrived at federal lines “shall be forever free of their servitude.” This represented an important change in emancipation policy—the first time that Congress brought freedom into the equation. William refused to enforce the bill’s freedom provision. Despite the fact that it seemingly authorized him with the power to declare enslaved people free, he held that only judges or courts had the power to adjudicate on an issue like freedom.

“I hold that I have no such power to ‘free a negro’ or ‘confiscate any estate,’” he told a friend, adding, “This is a judicial matter not mine.”

To John, he was much more direct, writing in September 1862, “I have your letter and Still think you are wrong in saying that Negroes are free and entitled to be treated accordingly by a simple declaration from Congress.” He would go on to argue that though universal emancipation would “of course be effectual” from a strategic standpoint, he felt it was “by no means conclusive,” especially if the army didn’t have “the machinery” to carry it out.12

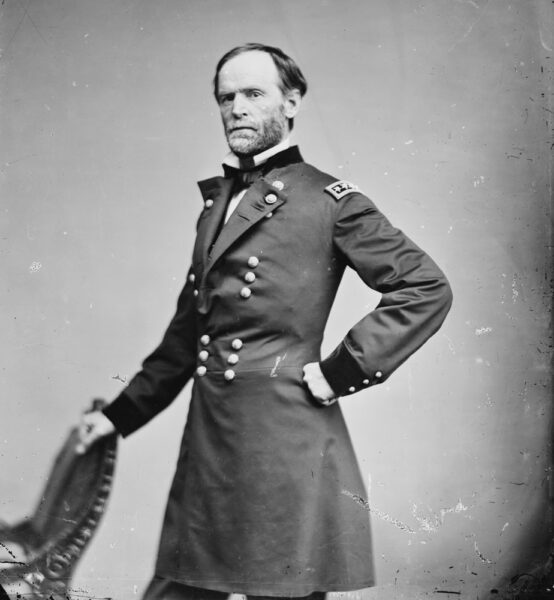

USAHEC

USAHECDespite his stubbornness on the issue of wartime emancipation, William Sherman’s army unwittingly became one of liberation on its march through Georgia and the Carolinas. Above: Slaves are depicted seizing their freedom by following Sherman’s army as it advances through the South.

John did his best to bring his brother around on the issue, writing that William should “presume the freedom” of refugees from slavery who reached his lines. But his elder held firm. He chastised John for thinking that politicians in Washington knew more than the generals made to manage the issue at the front. He also chided his brother on practical grounds, noting that it was hard enough to feed and provision his own men: “We cannot now give tents to our soldiers, and our wagon trains are now a horrible impediment, and if we are to take along & feed the negros who flee to us for refuge, it will be an impossible task,” he wrote.13

William maintained his position even after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which forever altered the meaning and purpose of the war. “They [freed people] are free but freedom don’t clothe them, feed them & shelter them,” he wrote to John. “The president declares Negros free, but makes no machinery by which such freedom is assured,” he complained, just before departing on the long campaign for Vicksburg. “I still see no solution of this Great problem except in theory,” he lamented to John, believing the issue was a social or political question and not a matter for him or his men. Their job was to wage war—and win.14

William’s obstinacy makes it all the more ironic that as he pushed out of Atlanta two years later, he would do so at the helm of an army of liberation. His famous advance through Georgia and the Carolinas, while remembered for the material devastation it wrought on the Confederate homefront, achieved in effect what the Emancipation Proclamation could only ever do on paper: It pummeled the planter class, leading to the destruction of slavery and the emancipation of tens of thousands of enslaved people. Sherman’s march through Georgia and the Carolinas probably represents the largest emancipation event in American history. So while William may have resisted emancipation as an official policy, he arguably did as much, if not more, than anyone to enforce it, making him, even if by default, one of the nation’s great liberators.

By the time William marched into the nation’s capital for the Grand Review of the Armies in late May 1865, “liberator” was a title he had grown more comfortable with. Despite his initial displeasure with emancipation, he eventually came to see it as a fait accompli and took pride in having helped stomp out the embers of a slave regime. His status as a great liberator was a label he now wore as a badge of honor, especially if it helped rebut allegations that he had failed to fully embrace emancipation or had once mistreated enslaved people.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressWilliam T. Sherman

Reconstruction was to pose a whole new set of questions, and again the brothers found themselves at odds over how to handle the war’s aftermath.

For one, they developed contrasting views of the new president, Andrew Johnson. John had served with Johnson in Congress, but it was on the stump during the election of 1864 that he began to appreciate Johnson’s future as a national figure in American politics. Like many others, John marveled at Johnson’s ability to whip up a crowd, which he had been doing since 1843, when the former accomplished tailor entered politics as a brawler from East Tennessee. Johnson entered the Senate in 1857, a few years before John, and gained recognition as the only southern senator not to resign his position as secession swept across the South. Lincoln viewed him as a Democrat he could trust, which is why he first tapped Johnson to serve as the military governor of Tennessee and later had him join his presidential ticket as a sign of national unity. The two men even shed their old political affiliations for a new one, running in 1864 as the “National Union Party.”

During Lincoln’s long and fateful campaign for reelection, John could have never guessed the trouble Johnson would eventually cause. Following Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865 and Johnson’s swearing in as president, a rift emerged. Though the new president promised to “make treason odious,” he eventually did the opposite. By the summer, he embarked on a pardoning spree of ex-Confederates; pardon seekers lined up at the White House for a chance to grovel at Johnson’s feet. Then, early the next year Johnson did the unthinkable: He vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 along with a bill to reauthorize the Freedmen’s Bureau, both of which had wide support in the Republican Party. Congressional Republicans and the nation’s chief executive were now clearly on opposite sides of a brewing battle over just how far Reconstruction should go.

Johnson’s skullduggery reopened the old conflict between John and William. Ever since Johnson’s swearing-in, William had been his steadfast supporter. He viewed Johnson’s leniency toward ex-Confederates as pursuing a “soft peace”—the necessary carrot to the bloody stick of William’s “hard war” tactics, the president a kindred spirit of sorts. To Sherman, Johnson was a realist who served as a necessary buffer against Radical Republicans in Congress, whom William viewed as extreme ideologues.

John disagreed. While he had held out hope for Johnson, it vanished after the president’s two vetoes. In the summer of 1866, he would vote with the party to override Johnson on both bills. By then, it wasn’t just the vetoes that divided the president from the Republicans in Congress. Expanding the right to vote to African Americans had emerged as the latest attempt by Congressional Republicans to make good on the promise of emancipation. Johnson again opposed the issue and, worse, was trying to parlay his opposition into support from southerners and Democrats, a power play that would neutralize Republican plans for Reconstruction. To John and others in his party, Johnson’s treachery seemed to know no bounds.

This new issue of black suffrage triggered a return to the Sherman brothers’ wartime debate over emancipation, now centered on emancipation’s most immediate legacy. As he had throughout the war, John supported expanding black rights. He had spoken out in favor of African-American suffrage in the Ohio gubernatorial election, considering it the morally correct action to take as well as the most politically expedient. He, like others, hoped enfranchising African Americans might generate a permanent Republican majority in the South.

William had other ideas. While he would eventually moderate his stance, he generally opposed expanding suffrage, seeing it as an unnecessary policy that might reignite tensions between North and South. Enfranchising formerly enslaved people represented a third-rail issue that southerners would never consent to, suggesting the likelihood of a renewed conflict between the two sections. Such a prospect had always colored William’s perception of the president’s approach to Reconstruction. As he told John in February 1866, “the President’s antagonistic position saves us war save of words, and as I am a peace man I go for Johnson and the Veto.”15

William would later publicly declare his support for Johnson about the time that his brother and other Republicans in Congress began plotting the president’s removal from office. As they had in wartime, the Shermans again found themselves at opposite ends of a key issue.

Bennett Parten is an assistant professor of history at Georgia Southern University and the author of the forthcoming book Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman’s March and the Story of America’s Largest Emancipation (Simon & Schuster, 2025).

Notes

1. Rachel Sherman Thorndike, The Sherman Letters: Correspondence Between General and Senator Sherman from 1837 to 1891 (New York, 1894), 157.

2. Ibid.

3. Brooks D. Simpson and Jean V. Berlin, eds, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860–1865 (Chapel Hill, 1999), 16.

4. M.A. DeWolfe Howe, ed. The Home Letters of General Sherman (New York, 1909), 162.

5. Ibid., 169.

6. Ibid.,163.

7. Thorndike, Sherman Letters, 78, 99.

8. Ibid., 120.

9. Ibid. 118

10. Congressional Globe, Senate, 37th Congress, 2nd Session, April 24, 1862, 1783.

11. Congressional Globe, Senate, 37th Congress, 2nd Session, April 2, 1862, 1491.

12. See Section 9 of the Second Confiscation Act. See also, Simpson and Berlin, eds., Sherman’s Civil War, 303, 293.

13. Thorndike, Sherman Letters, 78, 99.

14. Simpson et al., Sherman’s Civil War, 596.

15. Thorndike, Sherman Letters, 263.

Related topics: William T. Sherman