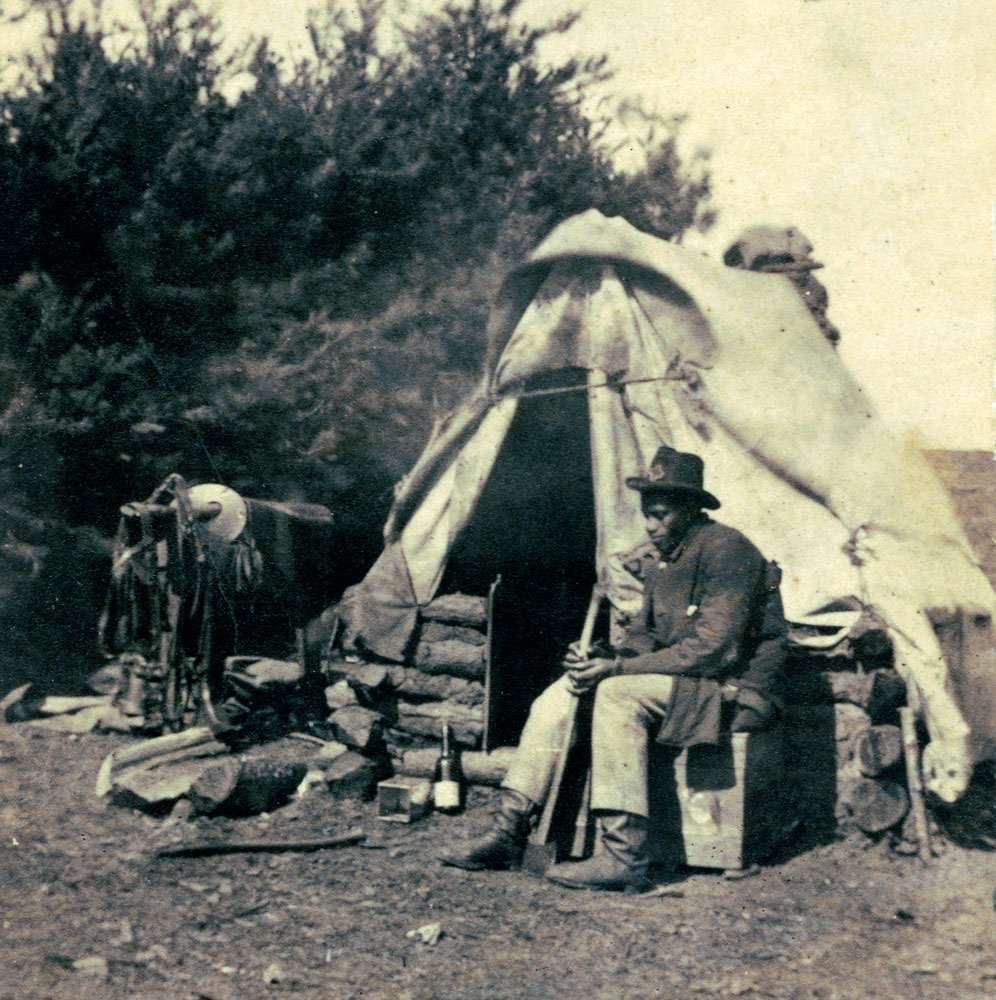

She•bang | noun | A strange word that had its origin during the late civil war. It is applied alike to a room, a shop, or a hut, a tent, a cabin; an engine-house.1

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAn unidentified soldier from the Union army’s X Corps sits outside his makeshift living quarters, or “shebang,” in an undated wartime image.

“I hardly think there will be a fight here at Fredericksburg, as we have orders to fix up our tents as though we were expected to stay here some time. The rebels seem to be buisy, building breastworks, and prepareing for us, but I should think it would not be much trouble for us to drive them out of Fredericksburg if we went about it,” wrote George Washington Whitman, an officer in the 51st New York Infantry, in a letter to his wife on December 8, 1862.2

Yet five days later, Major General Ambrose Burnside led the Army of the Potomac in a series of futile attacks against for tified Confederate positions west of the city on Marye’s Heights. Leaden bullets fell like hail, cutting down the men in blue. The 51st New York “was ordered to support a battery” and the Confederates “completely swept the position with grape and cannister and our battery was soon obliged to haul off with nearly half of their men either killed or wounded.” Once again ordered to the front, the regiment marched “in line of battle over a plain about 200 Yards wide that was entirely swept by the enemys guns.”

“We received the most terrific fire of grape, cannister, percussion Shell musketry and everything else, that I ever saw,” Whitman recalled.3 As the evening sun dipped below the horizon, dry grasses caught fire and screams of the dying filled the air as the Union army retreated across the Rappahannock River.

On the morning of December 16, the New York Tribune published a list of the regimental casualties for 51st New York, and included among them was “First Lieutenant G.W. Whitmore [sic], Company D.”4 Without waiting to learn the extent of his brother’s battlefield injuries, poet Walt Whitman packed a bag, borrowed $50 from their mother, and joined the throng of people rushing from New York City to Washington, D.C., to learn of their loved ones’ fates. After going from hospital to hospital without finding his younger brother, Whitman secured a pass granting him authorization to travel aboard a military train to Falmouth, Virginia, where the 51st New York was encamped. There was his brother, who had escaped the battle with only a gash on his cheek.5

“When I found dear brother George, and found that he was alive and well, O you may imagine how trifling all my little cares and difficulties seemed—they vanished into nothing,” wrote Whitman.6

Yet the journey changed Whitman. In the aftermath of the Battle of Fredericksburg, “one of the first things that met my eyes in camp, was a heap of feet, arms, legs, &c. under a tree in front of a hospital.”7 He witnessed, firsthand, “the way that hundreds of thousands of good men are now living, and have had to live for a year or more, not only without any of the comforts, but with death and sickness and hard marching and hard fighting.”8

Writing about his experiences in late 1862 or early 1863, he recalled the journey back to Washington. Before dawn, “the soldiers guarding the road came out from their tents or shebangs of bushes with rumpled hair and half awake look. Those on duty were walking their posts, some on banks over us, others down far below the level of the track.”9 Although applying a vernacular expression rapidly becoming commonplace among Union soldiers, Whitman’s wartime account was the first time shebang appeared in print.

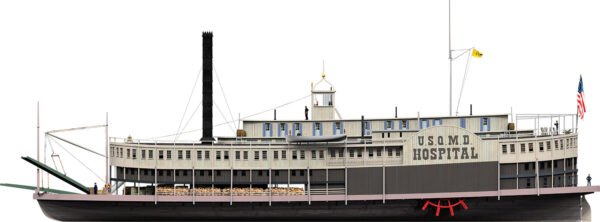

Distinguishable from a permanent dwelling, a shebang was a poorly made hut or shanty, oftentimes a temporary accommodation. During the war, Mary A. Livermore, a leading member of Chicago’s Northwest Branch of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, traveled south to provide care to Union soldiers hospitalized at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana. While in the vicinity, she journeyed inland to visit the soldiers of the Chicago Mercantile Battery, and “the boys swarmed from tents and ‘she-bangs’ … all shouting a hearty welcome.”

For her overnight accommodations, Livermore received the “best shebang of the encampment.” “Everything in the way of shelter, in camp parlance, that was not a tent, was a shebang,” she explained. “Mine was a rough hut made of boards, with a plank floor, roofed with canvas, with a bona fide glass window at one end, and a panelled door at the other. The furniture consisted of two bunks, one built over the other…. There was a rough pantry with shelves, holding rations, odd crockery and cutlery, … a home-made rickety table, a bit of looking-glass, sundry pails and camp-kettles, a three-legged iron skillet, and a drop-light, extemporized from the handle of a broken bayonet, and a candle, the whole suspended from the ridge pole by a wire.”10

In 1877, linguist John Russell Bartlett updated his Dictionary of Americanisms, adding myriad terms arising from “the late civil war.”11 One of those additions to the fourth edition was shebang: “a strange word that had its origin during the late civil war. It is applied alike to a room, a shop, or a hut, a tent, a cabin; an engine-house.”12

Shebang entered into common usage during the war as thousands of Union and Confederate soldiers found themselves sleeping in these shanties, but the term’s prewar origin is complex. Some linguists trace the term to Ireland where a shebeen or shebang indicated “a place where unlicensed liquor is sold.”13 Maximilian Schele De Vere’s Americanisms: The English of the New World (1872) attributed it to the French term cabane, claiming, “shebang … used even yet by students of Yale College and elsewhere to designate their rooms, or a theatrical or other performance in a public hall, has its origin probably in a corruption of the French cabane, a hut, familiar to the troops that came from Louisiana, and constantly used in the Confederate camp for the simple huts, which they built with such alacrity and skill for their winter quarters.”14

Publishing their Dictionary of Slang, Jargon & Cant in 1897, two British linguists traced the word’s origin to Hebrew: “Shebang (American), a shanty, or small house of boards. No one has ever explained the origin of this term, but it may be noted that there are exactly seven board-surfaces in a shanty, the four upright sides, the two sides of the roof, and the floor, and that the word shebang, in Hebrew, means seven.”15 Or, as others claimed, “any shanty where they play [gambling] at seven up.”16

American Freemasons attributed more symbolism to the number seven. “Among the Hebrews,” claimed A Lexicon of Freemasonry, in the 1850s, “the etymology of the word shows its sacred import; for, from the word שבע (shebang) seven, is derived verb שבע (shabang) to swear, because oaths were confirmed either by seven witnesses, or by some victims offered in sacrifice.”17 In 1854, a Pennsylvania newspaper, likewise, referred to an Odd Fellows Lodge as a “chebang.”18

The meaning of shebang expanded after the Civil War. In Roughing It (1873), Mark Twain wrote, “Say, Johnny, this suits me!—suits yours truly, you bet, you! I want this shebang all day. I’m on it, old man! Let ’em out! Make ’em go! We’ll make it all right with you, sonny!”19

Twain was referring not to a hut or shanty but to an omnibus or carriage. By the 1880s and 1890s, shebang referred to even more than a shack or vehicle.

Published in 1914, Henry Bradley’s A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles provided not one but three possible definitions for this “U.S. slang” term: 1a) “A hut, shed; one’s dwelling, quarters”; 1b) “Applied to a vehicle”; and 2) “More widely, almost any matter of present concern; thing; business; as tired of the whole shebang.”20

Since the 1990s, the word has added yet another definition—one that would have been unfathomable to Whitman and Twain. In Linux script, the shebang or hashbang (“#!”) character combination is currently used on the very first line of computer coding script to indicate which interpreter can process the commands in the digital file.21 This technical term is probably alien to most Americans today, who will instead hearken to the late-19th-century usage “the whole shebang,” when referring to the entirety of something. Although far from the soldiers’ shanties immortalized by Whitman, the Civil War-era usage of shebang lives on in conversation and of course in commerce. It is a branding tool to sell an array of spice mixes, hot sauces, and potato chips marketed as “The Whole Shabang Super-Seasoned Snacks.”

Tracy L. Barnett will receive her doctorate in American history from the University of Georgia in December 2024. Rifles—their meaning to men and their availability in 19th-century America—are at the center of her scholarship. With her feline familiar, she lives in Washington, D.C.

Notes

1. John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States, Fourth Edition (Boston, 1877), 578.

2. George Washington Whitman to Louisa Van Velsor Whitman, December 8, 1862, The Walt Whitman Archive. (Hereafter WWA.)

3. “Diary of George Washington Whitman, September 1861 to September 6, 1863,” December 13, 1862, WWA.

4. New York Tribune, December 16, 1862.

5. Roy Morris, The Better Angel: Walt Whitman in the Civil War (New York, 2000), 45, 47–51.

6. Walt Whitman to Louisa Van Velsor Whitman, December 29, 1862, WWA.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Walt Whitman, Specimen Days in America (London, 1887), 43–44.

10. Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War (Hartford, 1888), 304.

11. Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms, vi.

12. Ibid., 578.

13. James Maitland, The American Slang Dictionary (Chicago, 1891), 237; Max Cryer, Curious English Words and Phrases: The Truth Behind the Expressions We Use (New Zealand, 2012), 329.

14. Emphasis in the original. Maximilian Schele De Vere, Americanisms: The English of the New World (New York, 1872), 284.

15. Albert Barrère and Charles G. Leland Author, eds., A Dictionary of Slang, Jargon & Cant, Embracing English, American, and Anglo-Indian Slang, Pidgin English, Gypsies’ Jargon and Other Irregular Phraseology, Vol. II (London, 1897), 217.

16. Charles Godfrey Leland, Songs of the Sea and Lays of the Land (London, 1895), 189.

17. Although Albert G. Mackey conflated the Hebrew spelling of “seven” and “to swear,” the Hebrew spelling of “to swear an oath” is written as לְהִשָׁבַע. Albert G. Mackey, A Lexicon of Freemasonry: Containing a Definition of All Its Communicable Terms, Notices of Its History, Traditions, and Antiquities, and an Account of All the Rites and Mysteries of the Ancient World (Philadelphia, 1856), 438.

18. “Showing him the ‘Chebang,’” Raftsman’s Journal (Clearfield, PA), July 15, 1854.

19. Emphasis in the original. Mark Twain, Roughing It (Hartford, 1873), 326.

20. Henry Bradley, A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, Vol. VIII, Part II (Oxford, 1914), 656.

21. Abhishek Prakash, “What is Shebang in Linux Shell Scripting?” Linux Handbook.