Hope Never to See It Anderson Carman

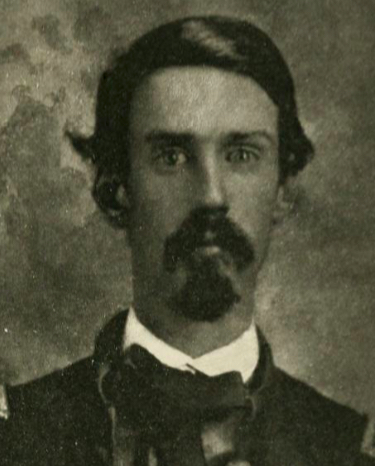

Anderson Carman

In this era of rapidly changing communications technology—alongside the growing ubiquity of misinformation—the need for professional historians to spread peer-reviewed scholarship outside their academic circles is more important than ever. That imperative is particularly pressing in the area of my own research, the Civil War’s “irregular” conflict. While the story of guerrilla violence and the Union army’s increasingly hard counterinsurgency policies may be known to academics like me and to dedicated history buffs, that story remains a sideshow for much of the American public. And with the country’s recent history of increasingly costly military occupations in places like Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, it’s important that Americans have a working historical knowledge of this type of unconventional combat.

That need motivated me to find an innovative way to synthesize the literature on Civil War guerrilla violence and bring it to a mass audience—without sacrificing any scholarly rigor. The result, Hope Never to See It (University of Georgia Press, 2025), is a graphic history that combines academia’s rigorous research processes with the comic industry’s talent for storytelling to take readers deep into the Missouri bush and unveil irregular conflict at its worst, men at their most stressed, and the laws of war at a breaking point.

In his 1838 book The Art of War, Swiss military officer and theorist Antoine-Henri Jomini called guerrilla-style violence “so terrible that, for the sake of humanity, we ought to hope never to see it.” Guerrillas have played a role in every American war since then. On the following pages, we highlight a sample from Hope Never to See It, with a behind-the-scenes look at how it came together. In the end, by sharing historians’ larger body of work on guerrilla and occupational violence, we hope the book influences the way readers think about this kind of irregular warfare, both as it occurred during the Civil War and how it continues in conflicts today.

The Process

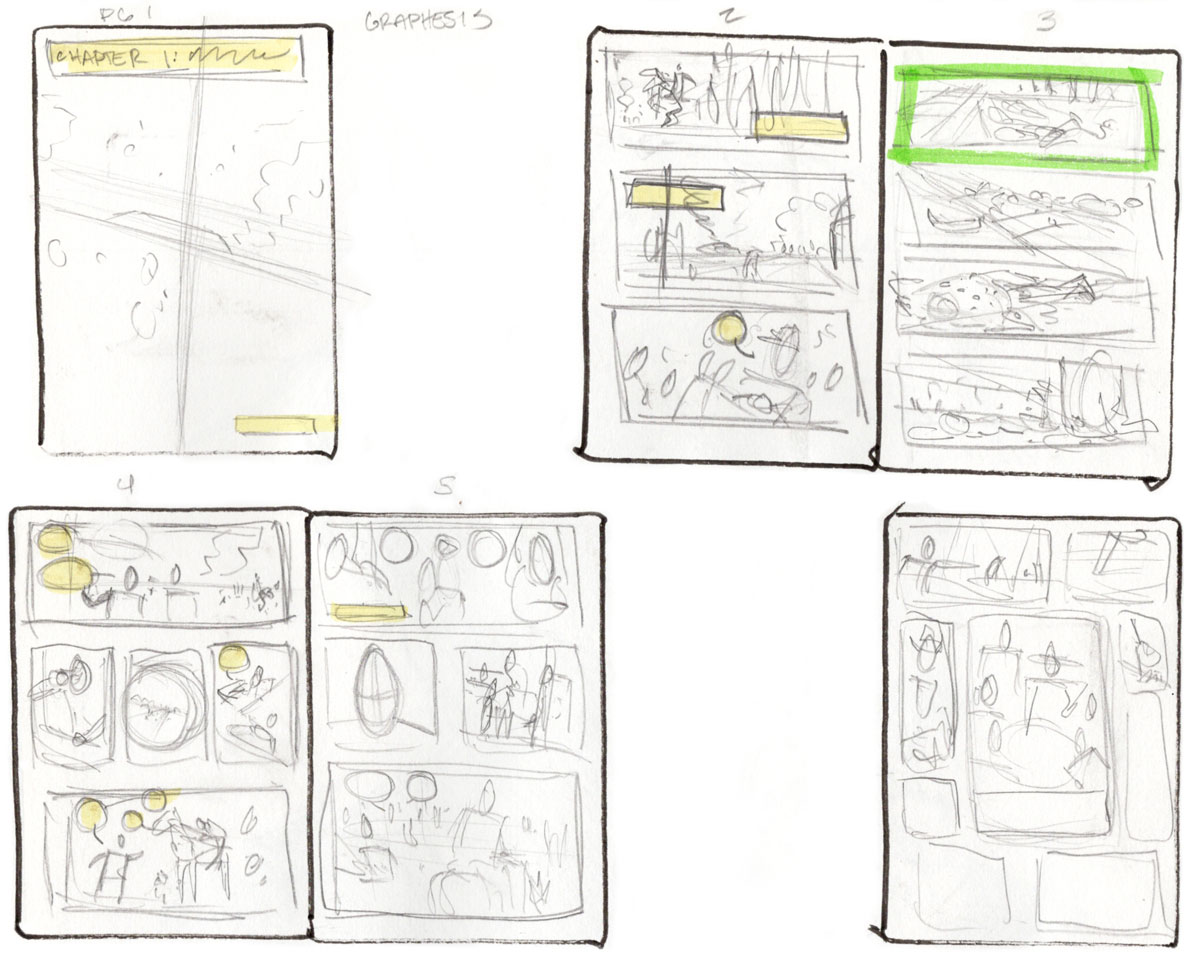

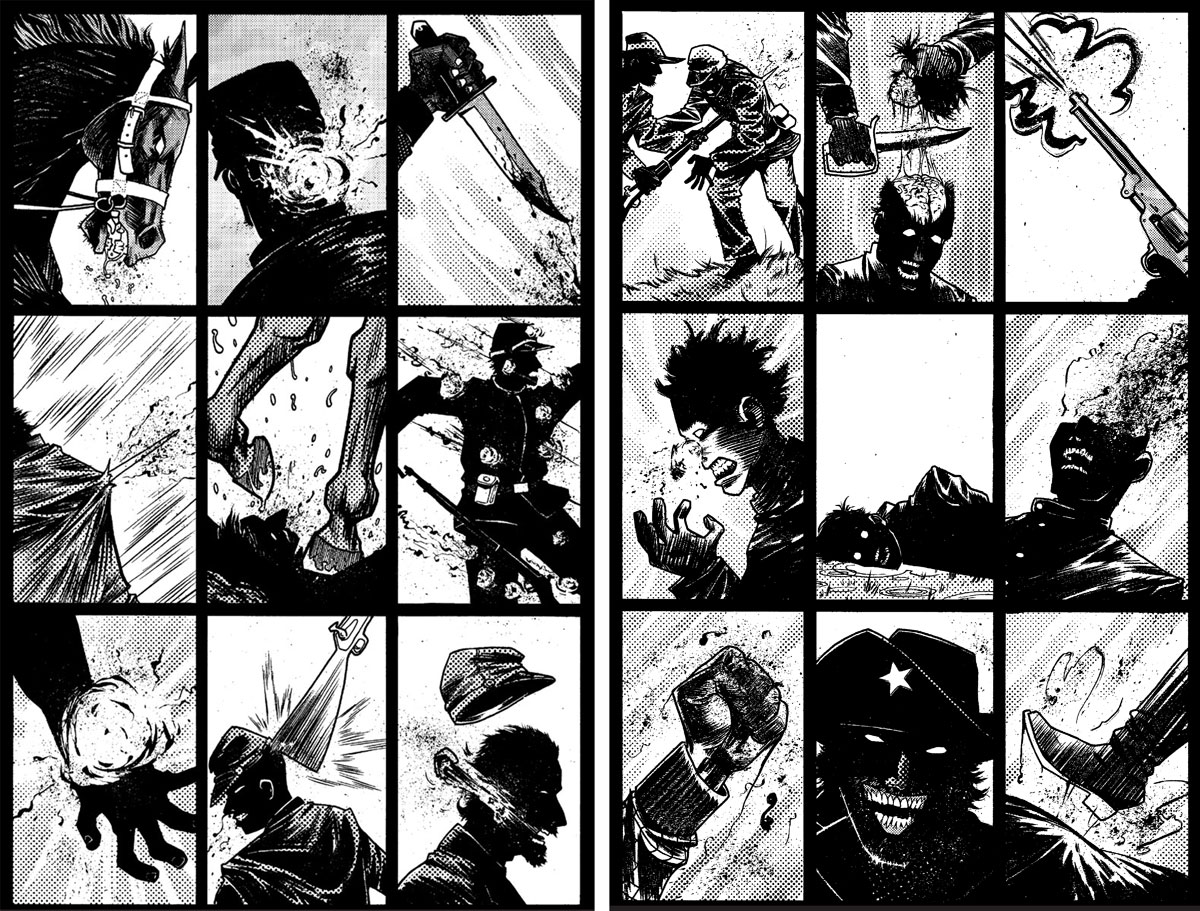

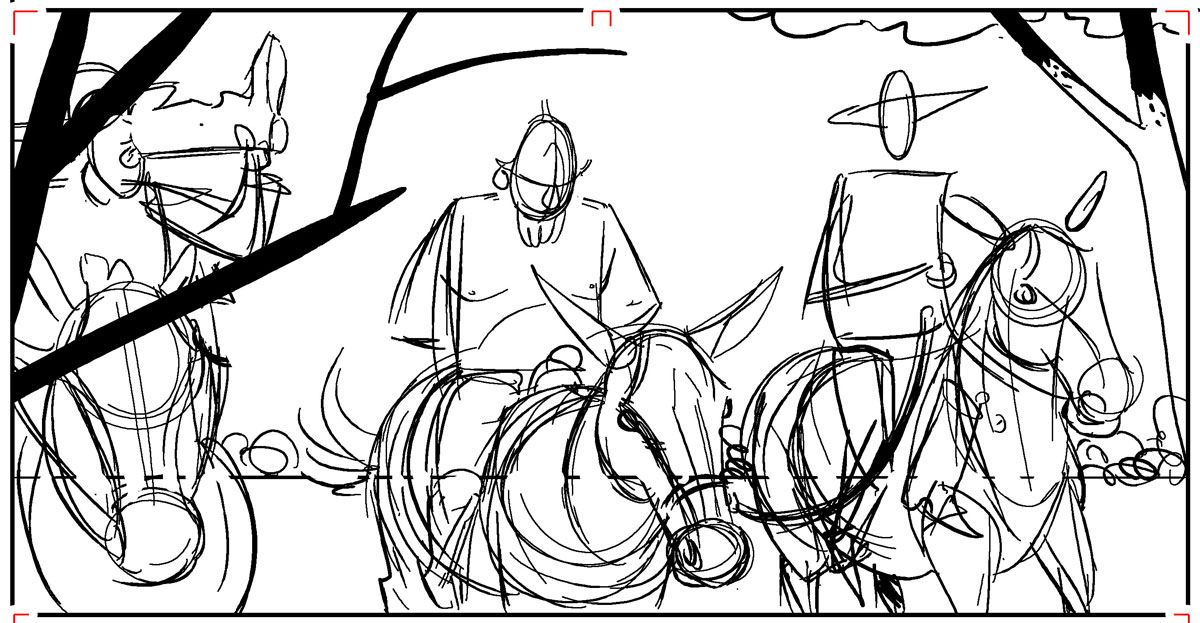

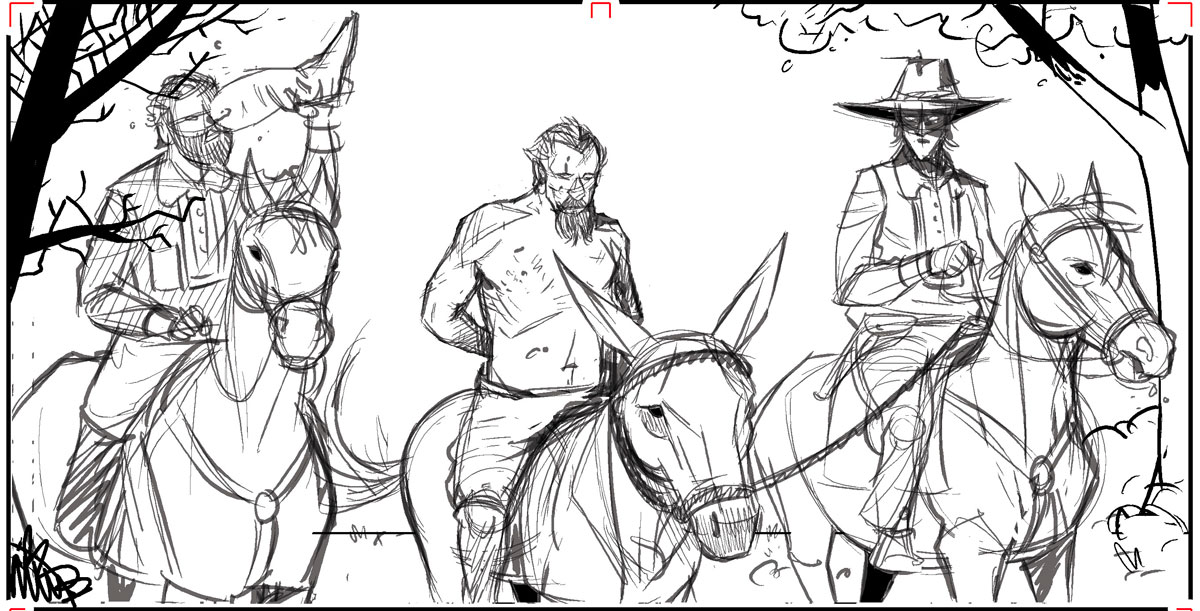

While unconventional in presentation, Hope Never to See It is not a work of historical fiction. The book is the product of a rigorous historical fact-checking process. We started with a script, which—from narrative descriptions to dialogue—is based on cross-checked, archival source material. Illustrator Anderson Carman then interpreted that script to produce a rough layout, or thumbnails (above).

We then collaborated on panel configuration and content details to produce a storyboard.

Storyboard Anderson Carman

Anderson Carman

Carman then penciled artwork, which, along with the script and endnotes, underwent a final round of scrutiny, making their way through the University of Georgia Press’ peer-review process.

Pencils Anderson Carman

Anderson Carman

Once all was approved, Carman inked the artwork.

Ink Anderson Carman

Anderson Carman

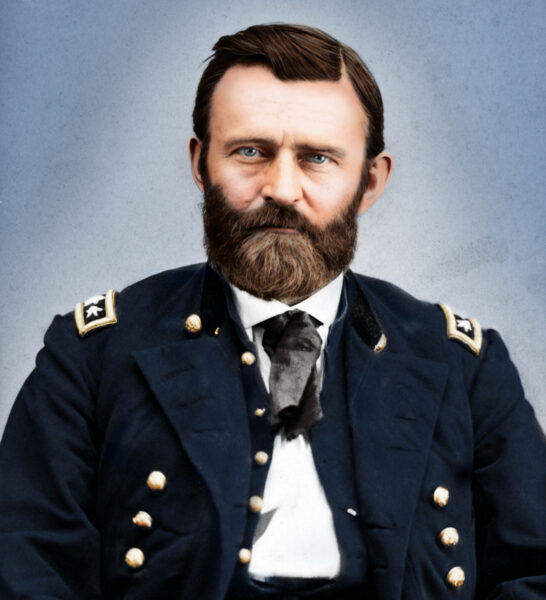

Whenever possible, Carman depicted the story’s characters from historical photographs. In other cases, character depictions are Carman’s interpretations based on demographic information available in census records (age, sex, race, occupation, etc.) and military records (height, weight, etc.). Furthermore, he depicted landscapes and ephemera—camp scenes, uniforms, weapons, buildings—based on historical photographs, typically those made by Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner.

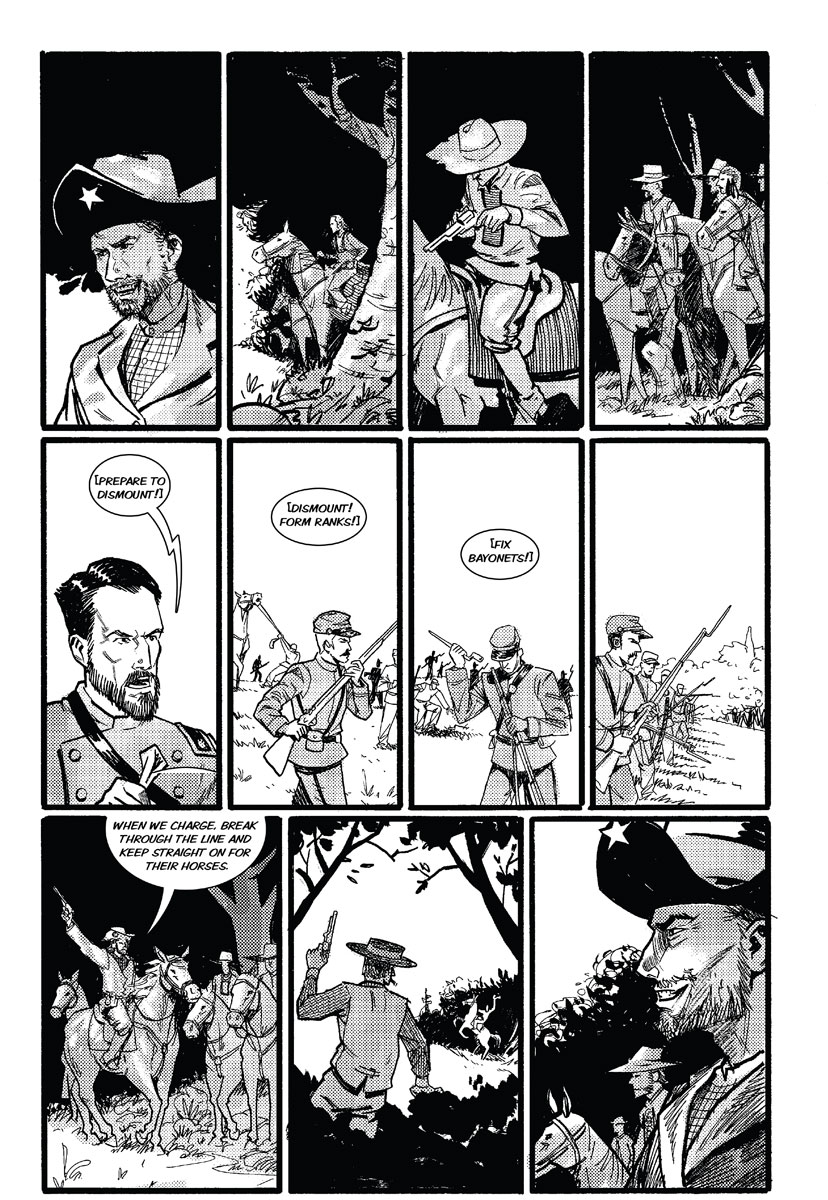

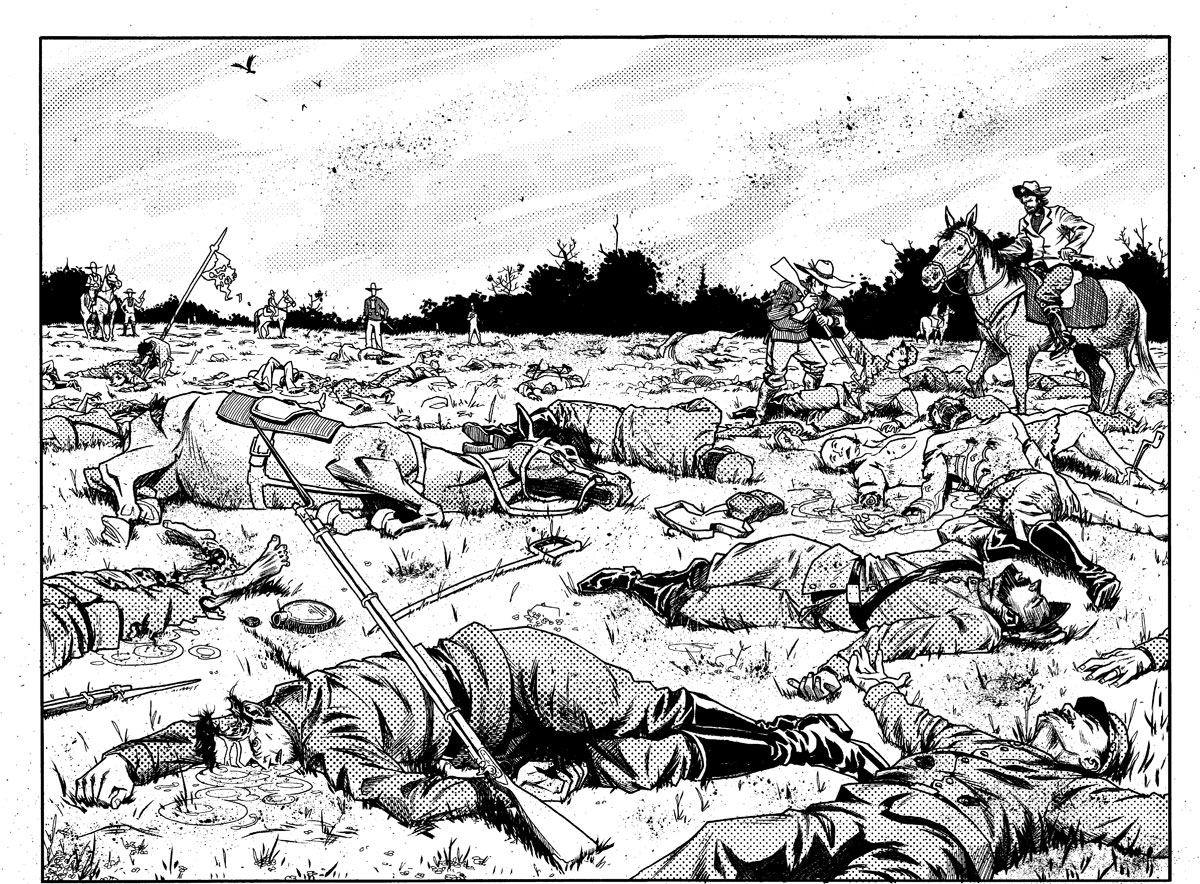

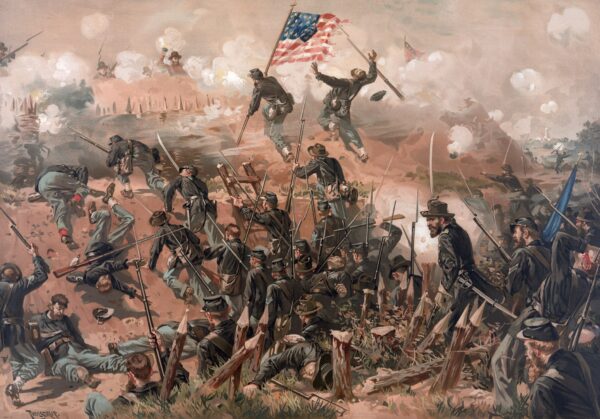

The book highlights two incidents of irregular violence in Civil War Missouri, one of which occurred outside Centralia on September 27, 1864. Guerrillas under “Bloody Bill” Anderson (shown here with a star on his hat) lured three companies of Union soldiers into an ambush. Major A.V.E. Johnston and the 39th Missouri Infantry rode to Centralia after seeing a plume of smoke from their post 20 miles away. They were greeted by a burned railroad depot, a looted town, and the mutilated remains of a recent guerrilla-led train-robbery-turned-massacre.

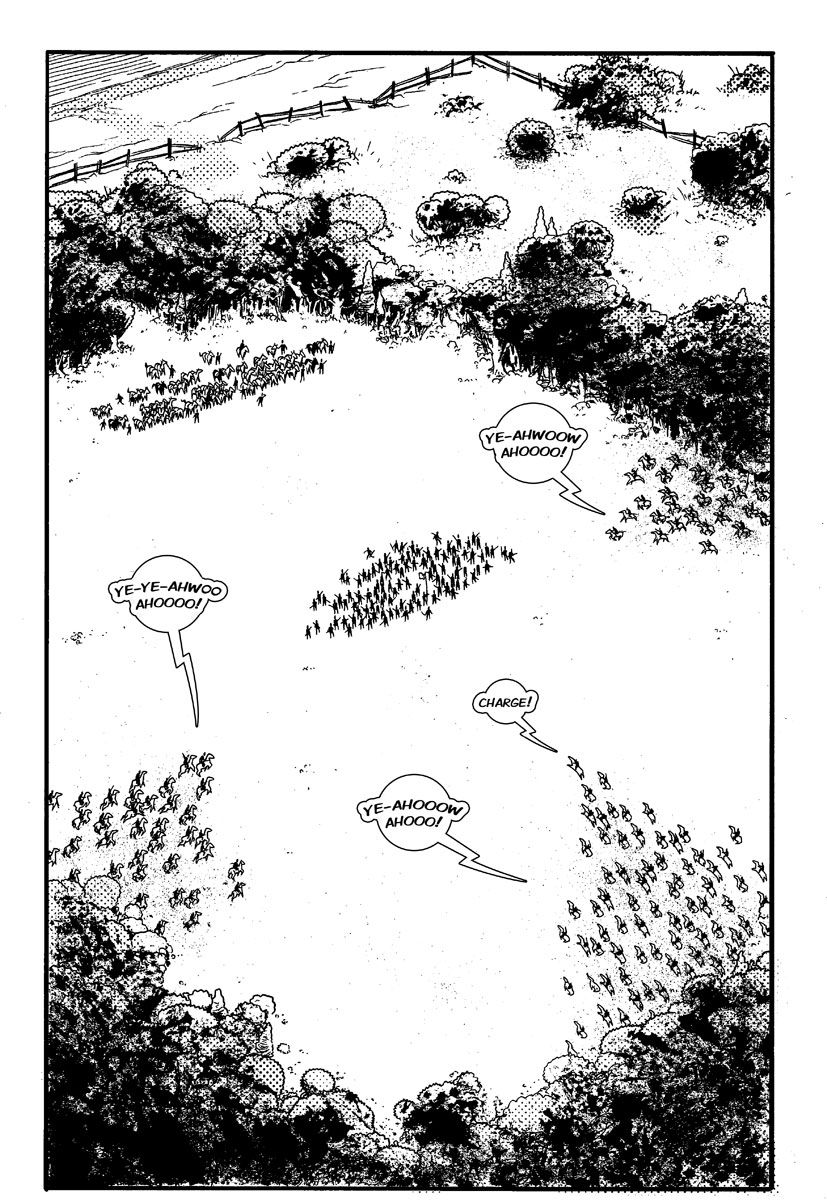

From a second-story window, Johnston spotted a small squad of mounted guerrillas leaving town (Anderson had directed them to be seen in hopes of encouraging the Union force toward a prearranged ambush site) and hastily pursued them into a field surrounded by thick timber before dismounting his troops. He did not realize he had led his approximately 150 men into a trap—the surrounding woods concealed Anderson’s waiting guerrillas—until it was too late.

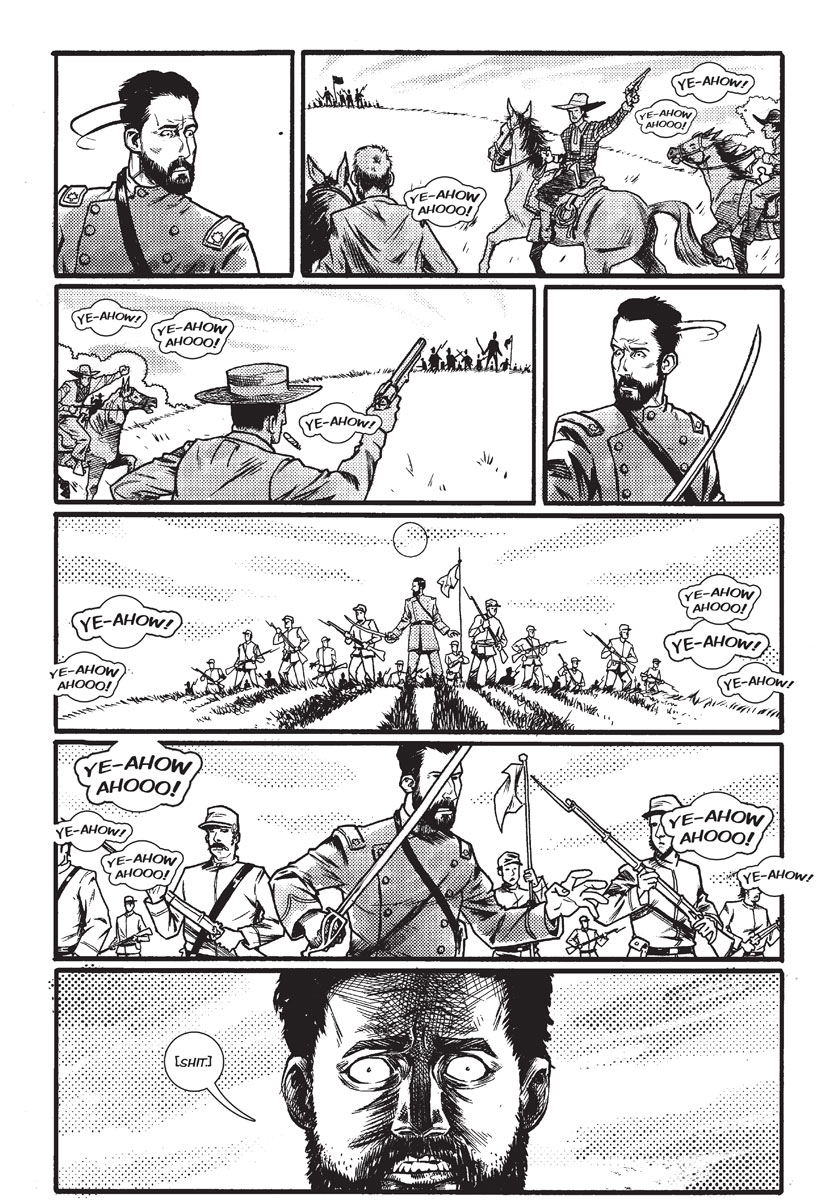

The guerrillas—approximately 400 of them—broke from their woodland cover, rushing on Johnston’s outnumbered men.

Some of Johnston’s men composed themselves long enough to fire a volley at the charging Rebels. The bullets whizzed over the heads of the oncoming guerrillas, who quickly overwhelmed the Union soldiers, nearly all of whom, including Johnston, were killed.

Multiple primary sources—including official reports, newspaper coverage, and a Union survivor’s account—confirm that some guerrillas mutilated Union soldiers’ bodies in the bloodletting. We debated how to depict this without displaying gore only for its theatrical impact. In the end, we decided to illustrate this brutal violence in silhouette—and not to depict the instances of genital mutilation that were reported (shown above). We also transcribed all of the primary sources about the violence we found and included them in the book’s endnotes.

Brady’s and Gardner’s images of Civil War battlefield dead inspired this scene of the aftermath of the massacre. Multiple sources indicate that Union soldiers’ bodies had fallen close enough together that a guerrilla played “floor is lava” on them—jumping from one body to another without touching the ground.

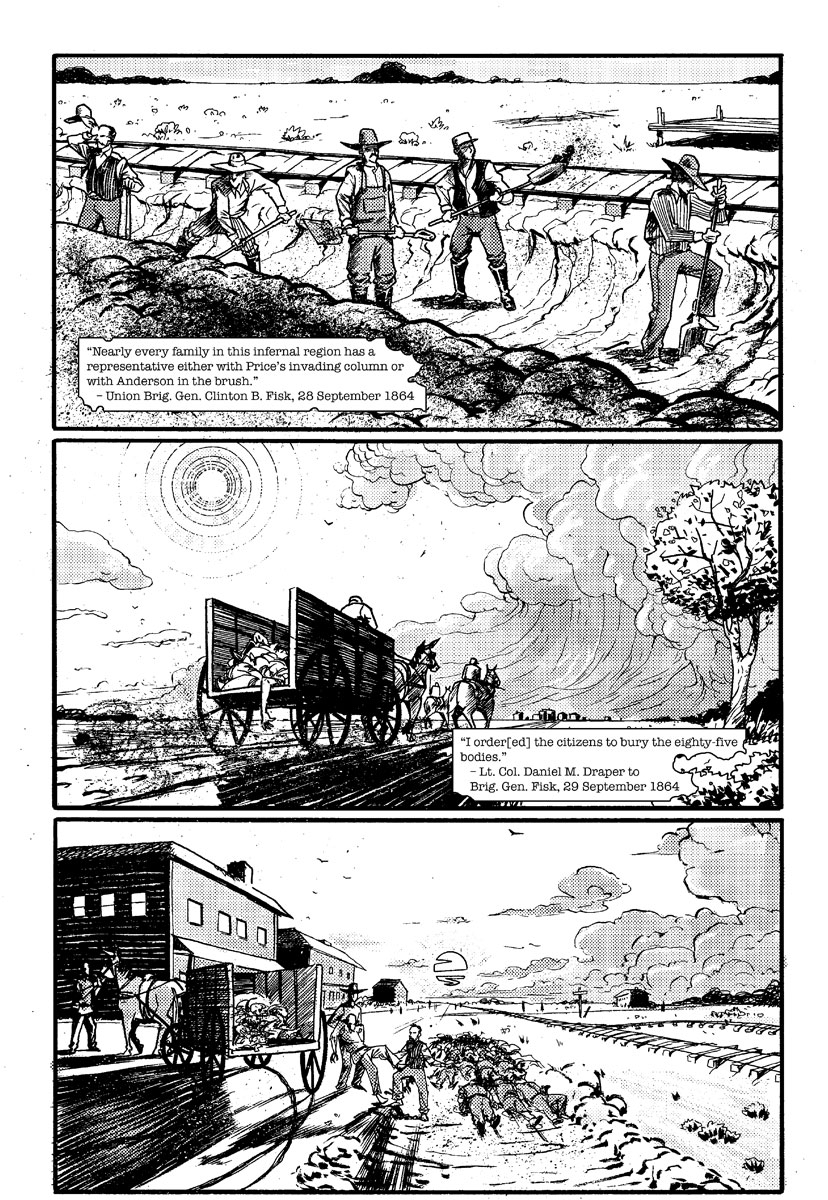

Historian Drew Gilpin Faust’s 2008 book, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, inspired these illustrations. Faust argued that the work of dealing with the war’s unprecedented death toll challenged Americans’ “most fundamental assumptions of life’s value and meaning.” Our aim with these scenes was to illustrate the horror of that challenge.

In addition to dealing with the death wrought by irregular violence, this page highlights the intimate connection between civilians and guerrillas—one that undermined the laws of war, dictated the U.S. military’s counterinsurgency policies, and influenced vigilante violence long after the conflict’s formal conclusion. Hope Never to See It explores these themes in depth.

Andrew Fialka is associate professor of history at Middle Tennessee State University. His research uses spatial analyses to interpret guerrilla violence. He lives in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Anderson Carman is an award-winning illustrator and sequential artist specializing in traditional ink, watercolor, and digital illustration in Atlanta, Georgia.