In the fall of 1860, Abraham Lincoln seemed unlikely to win future renown either as a president or an intuitive military genius. Aside from a few weeks in the militia in 1832—something he joked about—the Republican candidate possessed no military expertise. Democrats targeted him as antiwar because of his opposition to the Mexican War. As a congressman, he had voted against funding West Point and ridiculed military pomp. Yet he is remembered today as the nation’s greatest wartime president. How that happened is a complicated tale of history and memory, but it begins with Lincoln’s sometimes troubled apprenticeship as commander in chief in the Civil War’s first years.1

Until December 20, 1860, when South Carolina seceded, President-elect Lincoln had assumed the disunionists were bluffing. A day later, he began writing confidential letters to Republican leaders supporting the use of force if ultimately necessary to preserve the Union, although even then he could only imagine a limited conflict. In one of them, he sent word to Winfield Scott, commanding general of the U.S. Army, to prepare to “either hold, or retake” federal forts in Charleston “after the inauguration.”2 Corresponding further with Scott, Lincoln sketched out nascent strategic views that centered on holding or retaking other federal properties in the seceding states. By March 4, 1861, cautioned by his advisers not to risk further agitating southern secessionists, Lincoln pledged in his inaugural speech only to “hold, occupy, and possess” federal property. He further swore off any aggression or preemptive strike, assuring secessionists that “in your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.”3

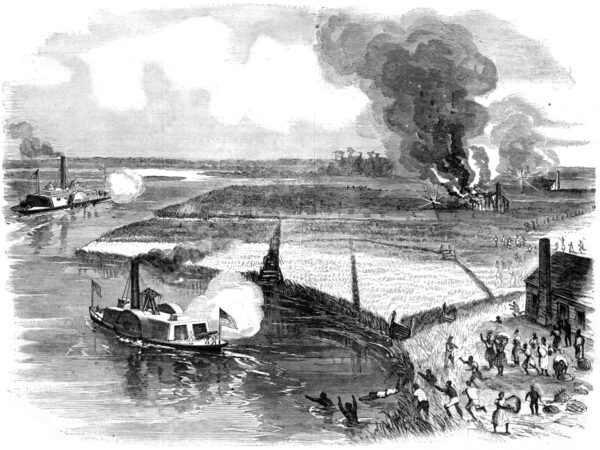

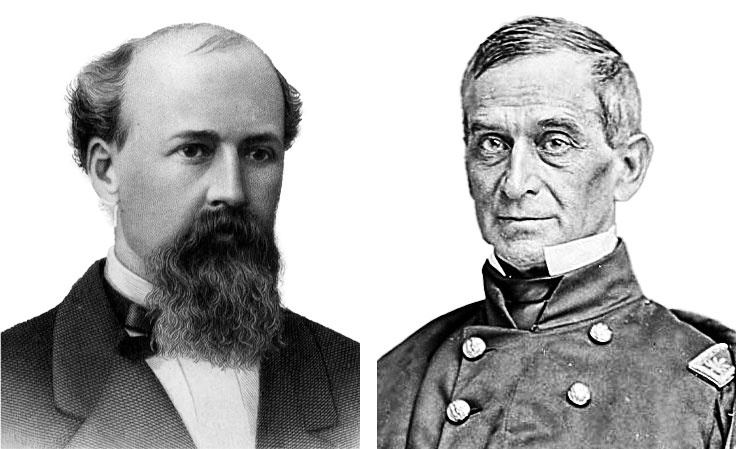

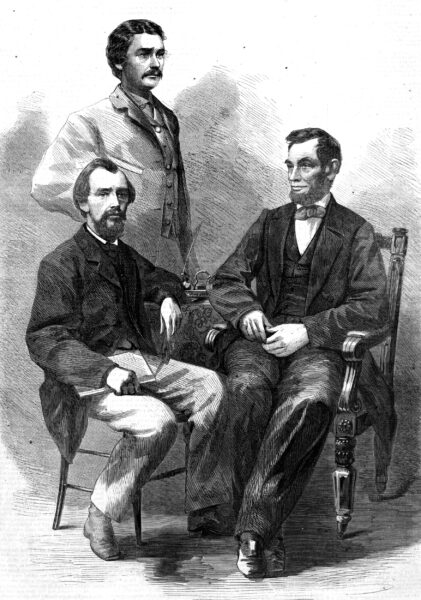

USAHEC (Fox); National Archives (Anderson)

USAHEC (Fox); National Archives (Anderson)Gustavus Fox (left) and Robert Anderson

Lincoln assumed that day that he still had time to reach a peaceful solution to the crisis. One day later, he learned the federal garrison at Fort Sumter was running out of food. Scott advised evacuation. Except for Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, the balance of Lincoln’s cabinet agreed, rejecting an aggressive plan suggested by former naval officer Gustavus Fox (Blair’s brother-in-law) to run the secessionist batteries and resupply the fort. But Lincoln liked Fox’s idea and refused to bow to Scott’s military expertise. He also feared that Republicans would turn on him if he abandoned Fort Sumter. Nor did he quite trust Colonel Robert Anderson, the southerner commanding the garrison. Prone to deliberateness in decision-making, Lincoln was not sure what else to do. His inaugural pledges to reject secession and hold federal properties, but also to not fire the first shot, boxed him in. Hoping to buy time, he sent Fox and two others to Charleston. Their reports were dim: Unionism was dead in the city and Anderson could hold out only to mid-April. The news depressed Scott so much that he advised evacuating both Sumter and Fort Pickens, near Pensacola, Florida, the only other significant federal post left in the self-proclaimed Confederacy. Ignoring the advice of most of his cabinet, Lincoln again rejected Scott’s counsel.4

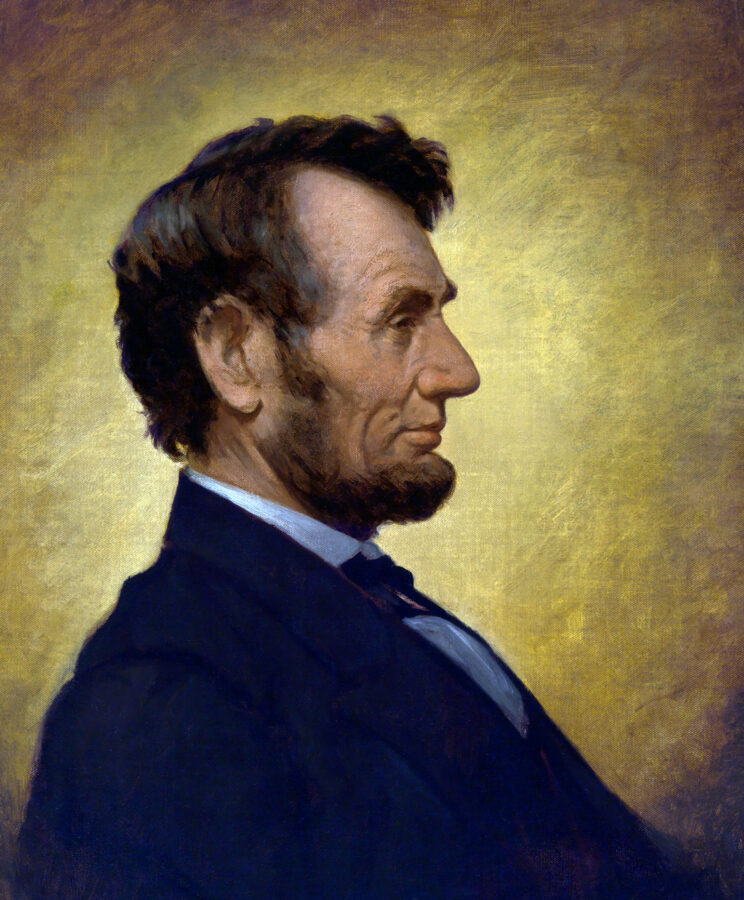

National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GalleryEarly in his presidency, Abraham Lincoln’s barely rudimentary knowledge of military and executive matters manifested itself in many ways, including his support for the ambitious plans of his young and inexperienced former law clerk, Elmer Ellsworth.

Risking war was not easy for a new president lacking both military and executive backgrounds. One example of Lincoln’s inexperience was his enthusiastic support of a bizarre plan hatched by a young favorite, Elmer Ellsworth. Despite no actual military experience, Ellsworth’s passion in life was militia drill. Having studied the Zouave soldiers (the French colonial troops in Algeria) with their quick drill and fanciful turbaned uniforms, he taught himself French and mastered their manual. In 1860, his Chicago-based United States Zouave Cadets toured the North and launched a Zouave fad with their mock battles and exciting performances. Among his fans was Lincoln. Ellsworth, who subsequently clerked for Lincoln the lawyer in Springfield, became an active participant in the presidential campaign. After his inauguration, Lincoln proposed making Ellsworth, 23, the chief clerk in the War Department. Ellsworth countered with an even more ambitious plan. He convinced Lincoln to create a new federal Bureau of Militias, with Ellsworth serving as adjutant and inspector general. The new bureau would coordinate organizing and equipping state militia units while providing standard drill and moral parameters. In essence, Ellsworth would become the nation’s drillmaster. Lincoln beamed that his untried young protégé possessed “a real genius for war.” The military establishment was aghast, however, and the plan went nowhere when Attorney General Edward Bates warned Lincoln that the whole scheme was unconstitutional.5

The Ellsworth gambit was only one example of Lincoln’s shaky beginnings as commander in chief. Anxiety, inexperience, and confusion would stalk him. So did Secretary of State William Henry Seward, who had expected to receive the Republican nomination for the presidency in 1860 until Lincoln defeated him at the Chicago convention. Seward initially had little respect for the prairie lawyer. Imagining himself as a sort of prime minister, he went over the president’s head to engage in covert talks to prevent Virginia’s secession, offering to evacuate Fort Sumter without a fight. Seward also concocted the odd diversion of reinforcing the relatively unimportant Fort Pickens on the Florida coast. Lincoln approved. Seward then convinced Lincoln not to tell anyone, including Scott, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, and Secretary of War Simon Cameron. Planning for the Pickens and Sumter operations proceeded in parallel silos until Lincoln blundered egregiously, assigning to both the most powerful ship available, USS Powhatan. He later confessed that he signed a stack of orders Seward gave him without reading them. Welles later complained that Seward’s real aim in sending the ship to Florida was to kill the Sumter expedition entirely by denying it the protection of Powhatan’s 16 guns. Lincoln apologized, but the damage was done. That ship had sailed—to Florida, not Charleston.6

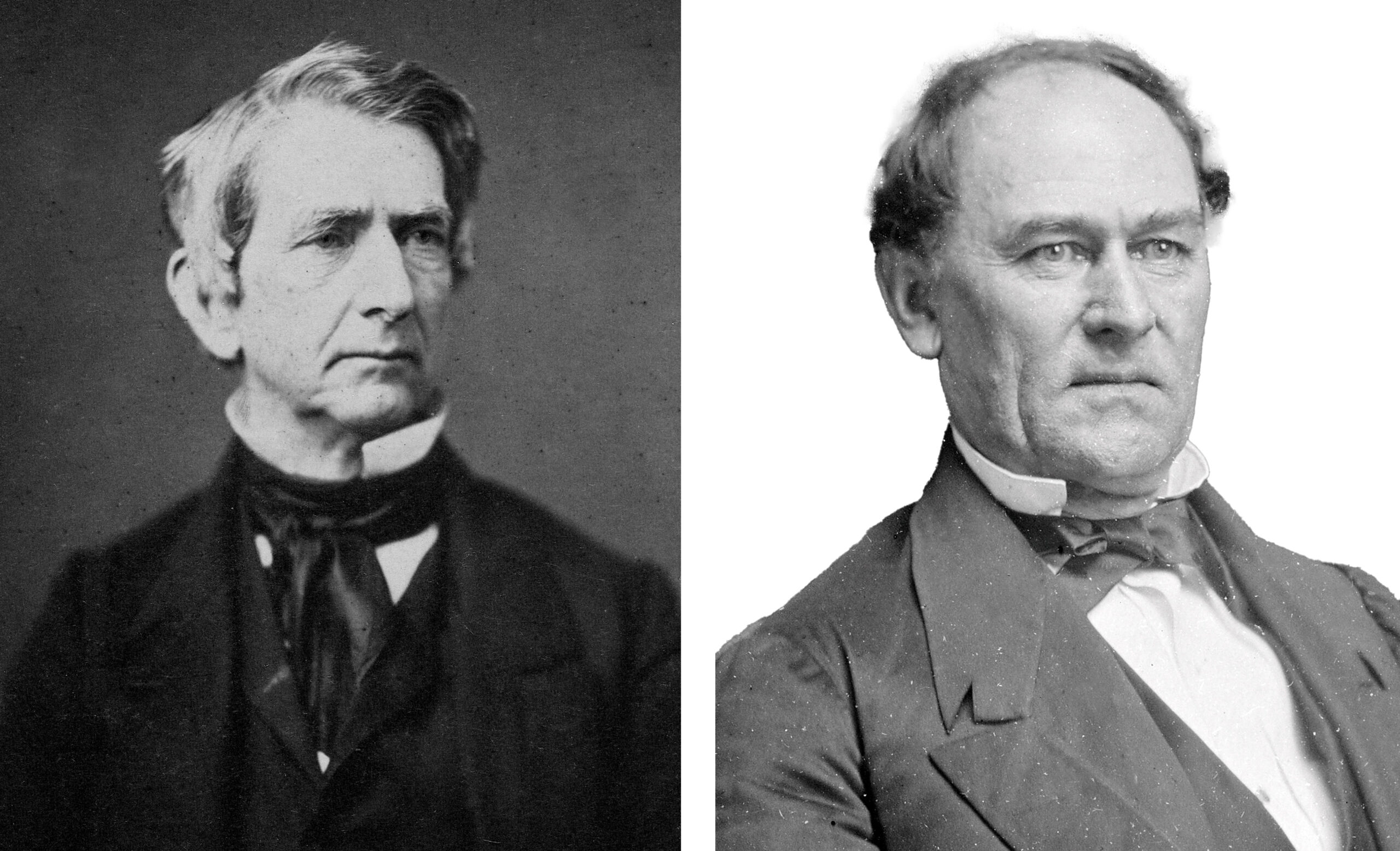

National Portrait Gallery (Seward, Browning)

National Portrait Gallery (Seward, Browning)William Henry Seward (left) and Orville Browning

On April 6, Lincoln dispatched the Fort Sumter expedition under Fox to feed the garrison. While he hoped the Confederates would let the relief party land, he expected resistance. Before dawn on April 12, Confederate shore batteries opened fire on Fort Sumter. Denied Powhatan’s covering firepower—an uninformed Fox awaited the ship in vain—no supplies landed. Anderson surrendered 34 hours later. Farther south, U.S. Marines easily secured Fort Pickens. Afterward, Lincoln insisted that he had made no mistakes. His friend Orville Browning, the Illinois senator, wrote weeks later that Lincoln told him, “The plan succeeded. They attacked Sumter—it fell, and thus, did more service than it otherwise could.”7 This was spin. Lincoln’s halting response from the inauguration to the attack on Sumter reveals no concise “plan” at all beyond keeping his vows to the voters to resist secession, accept a limited military solution if necessary, and not fire first.

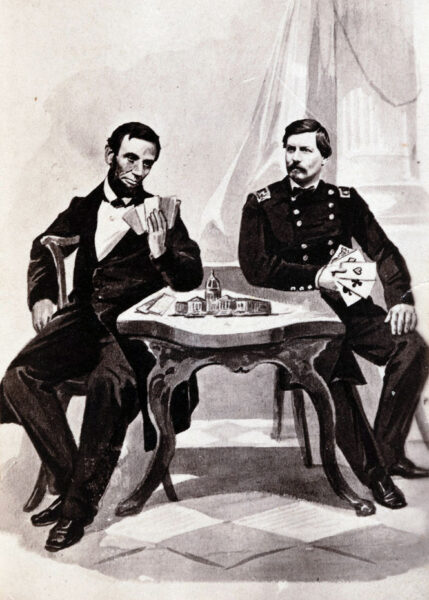

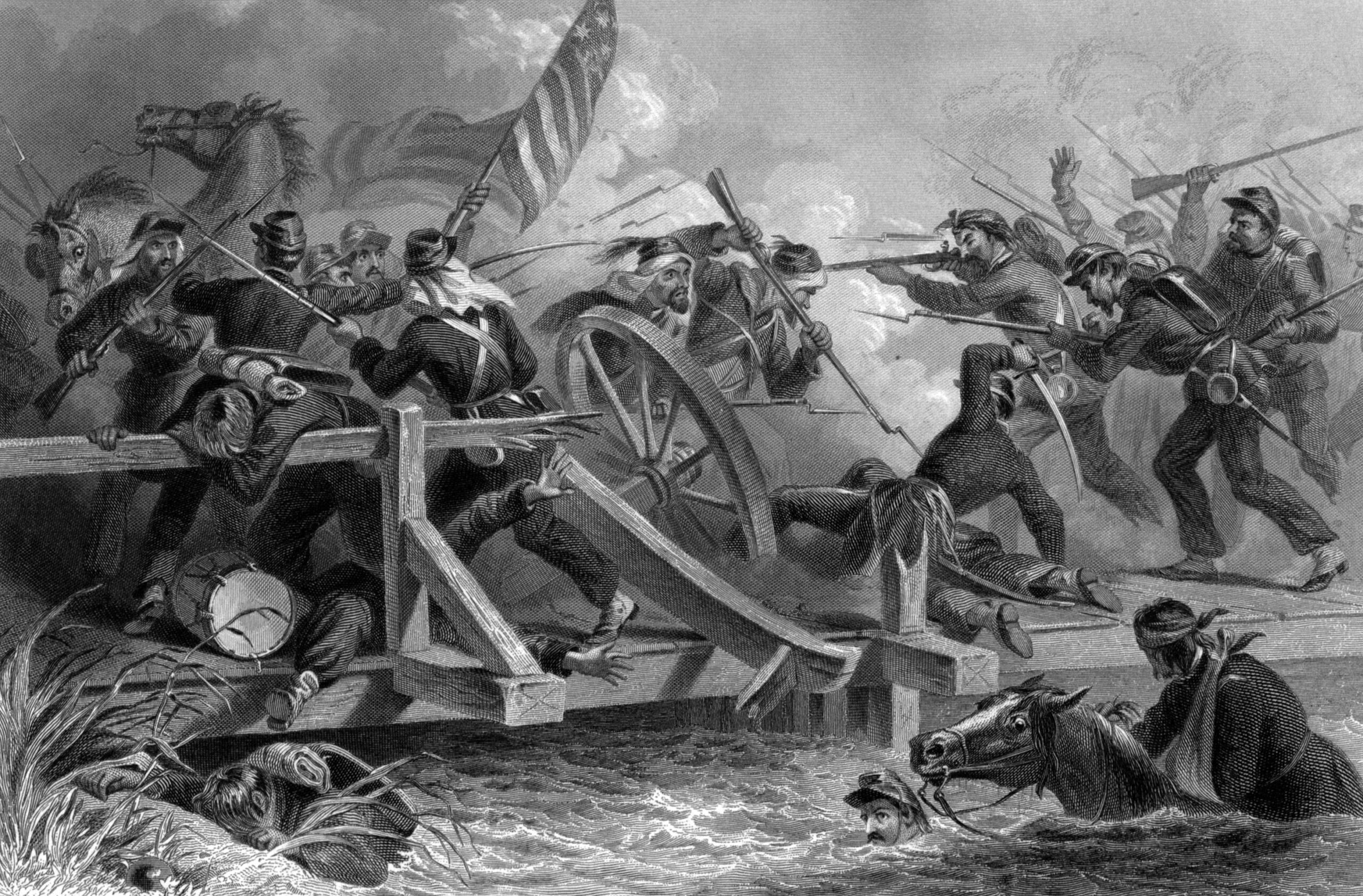

The War with the South, vol. 2 (1862)

The War with the South, vol. 2 (1862)The Union army’s defeat at the Battle of Bull Run (depicted above in an illustration by F.O.C. Darley) changed Lincoln’s perspective on the war, and prompted him to craft a nine-point memorandum on “Military Policy,” his most extensive strategic vision to date.

Once the shooting started and Virginia seceded, Lincoln still expected to send troops “down to Charleston” to “pay her the little debt we are owing her,” but he realized that first he needed to secure Washington, Baltimore, and Fort Monroe, on Virginia’s Peninsula.8 While he envisioned a limited east coast war, with a naval blockade of southern coasts doing the rest, others saw a larger conflict unfolding. On April 27, four days after assuming command of all volunteer troops in Ohio, George B. McClellan sent Scott an unsolicited plan to win the war. He imagined massive armies, coordinated and decisive campaigns across the Confederacy, and gentle treatment of white southerners to hasten reunion. Like many West Pointers and Mexican War veterans, McClellan distrusted volunteers and was wary of costly frontal assaults. Scott passed McClellan’s thoughts on to Lincoln, with his reservations. Even more convinced than McClellan that many white southerners still supported the Union, Scott was loath to send armies across their territory, sowing seeds of resentment and hatred. Better to build up the army, isolate the Confederacy with the blockade, and launch a campaign down the Mississippi River. In time, the bisected and isolated Confederacy would implode. Scott’s “Anaconda” plan, once it was leaked, met with derision.9

Library of Congress

Library of CongressIn the wake of the defeat at Bull Run, Lincoln ignored the chain of command by bringing George McClellan (above) to Washington to rebuild the beaten army and draw up new war plans, bypassing General-in-Chief Winfield Scott.

The Confederates recast the situation in early May when they moved their capital from Alabama to Virginia. Lincoln suddenly faced numerous pressures to respond. The Senate debated New York editor Horace Greeley’s demand for a quick march to Richmond. The 90-day enlistment terms of early war volunteers would soon expire, European involvement on behalf of the Confederacy remained a possibility, and the federal government was running on borrowed money. In response, Lincoln grasped Brigadier General Irvin McDowell’s proposal to march his gathering Army of Northeastern Virginia (the nucleus of the future Army of the Potomac) to Richmond via Manassas, hoping to end the widening conflict quickly.10 In historian T. Harry Williams’ words, Lincoln “initiated and planned” the war’s first major campaign, “forced” it upon Scott, and hurried McDowell. Doing so comprised the “first important exercise of his power as commander in chief.”11

It almost worked. On the morning of July 21, McDowell attacked the enemy at Manassas. At first, McDowell’s army seemed destined for victory, but a Confederate counterattack that afternoon sent his men reeling back to Washington in defeat. Afterward, Lincoln feared viscerally for the safety of the capital and the potential ramifications of losing it; he never really recovered from the shock. As White House secretaries John Nicolay and John Hay recalled, “all available troops were hurried forward to McDowell’s support; Baltimore was put on the alert; telegrams were sent to the recruiting stations of the nearest Northern States to lose no time in sending all their organized regiments to Washington; McClellan was ordered to ‘come down to the Shenandoah Valley with such troops as can be spared from Western Virginia.’”12

Manassas changed Lincoln’s perspective on the war. Ignoring Scott but still influenced by the general-in-chief’s views of a continental war effort, Lincoln on July 23 compiled a nine-point memorandum on “Military Policy.” It was his most extensive strategic vision to date. Some of it already was familiar, such as the blockade and maintaining control of Washington, Baltimore, and Fort Monroe. But Lincoln now also called for reinforcing troops in western Virginia. He looked west for the first time, directing Major General John C. Frémont to build an army in Missouri. On July 27, Lincoln added two more items to his list of priorities: first, control of Manassas and its railroads to Washington and Harpers Ferry; and second, “a joint movement” of two armies from Cairo, Illinois—one down the Mississippi to Memphis, the other from Cincinnati into East Tennessee, where diehard Unionists had won his admiration.13 “Lincoln never swerved from his memorandum of July 27, 1861,” historian and soldier Francis V. Green wrote nearly a half-century later.14

But he did tack and jibe. A month after Manassas, Lincoln brought McClellan to Washington to rebuild the beaten army. In a new proposal that Lincoln solicited from him directly, bypassing Scott (ignoring the chain of command became a common and corrosive feature of the Lincoln presidency), McClellan again envisioned massed armies launching coordinated Federal thrusts meant to smother the Confederacy in its crib. The main effort would take place in Virginia, where McClellan now found himself. The young general would lead an army of 273,000 men (including all the army’s regulars) out of Washington and march it clockwise along the Confederate coast to New Orleans. Smaller armies would operate on the Mississippi River, in East Tennessee, and in the southwest. When his plan went nowhere due to the cost, manpower, and time required, McClellan, at the president’s request, sent a new proposal that still involved massing a huge army in Virginia.15 Scholars usually chide McClellan as unrealistic, but as historian Donald Stoker observed, he at least saw the need for “unity of command and planning, coordinating various armies, vigorous action, viewing the various fields of conflict as parts of a contiguous whole…. He was also correct to think of targeting the Confederate army; Lincoln would come to the same conclusion.”16

Nor was McClellan alone in drawing up questionable campaign plans that autumn. Lincoln did too. In October, British war correspondent William Howard Russell was at McClellan’s headquarters when the president—“a tall man with a navvy’s cap, and an ill-made shooting suit, from the pockets of which protruded papers and bundles”—arrived. Lincoln asked to see “George,” only to be told that McClellan was resting. “This poor president,” Russell wrote afterward, was a man to be “pitied … trying with all his might to understand strategy, naval warfare, big guns, the movements of troops, military maps, reconnaissances, occupations, interior and exterior lines, and all the technical details of the art of slaying.” Lincoln, Russell continued, “runs from one house to another, armed with plans, papers, reports, recommendations, sometimes good humoured, never angry, occasionally dejected and always a little fussy.”17

Often obscured in the perpetual fascination with the deteriorating Lincoln-McClellan relationship that fall are Lincoln’s evolving military ideas. He increasingly championed a campaign into Confederate-controlled East Tennessee, not only to liberate its Unionist population (tales of whose suffering he had heard throughout recent months), but also to gain control of the vital railroad supply line that ran through the region and connected Richmond to the rest of the South. Around October 1, after Confederate forces violated neighboring Kentucky’s declaration of neutrality by occupying the strategically important town of Columbus, Lincoln drew up a plan for securing East Tennessee in the form of a memorandum (not an express order), which he delivered to the War Department. Union forces would seize and hold “the railroad connecting Virginia and Tennessee” in conjunction with a planned naval campaign against Port Royal, South Carolina, designed to acquire a safe harbor to be used as a base of future operations along the southern coast. Lincoln’s vision was so detailed that he even suggested specific troop movements and the establishment of various supply lines. The War Department and Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, who had principal military responsibility in Kentucky as commander of the Department of the Cumberland, were “in no mood for the enterprise” and dismissed the memorandum out of hand as foolishness. Lincoln had also suggested an additional western “plan of campaign” in Missouri, but it too went nowhere.18 Yet he was learning. In addition to setting strategic goals, Lincoln by October 1861 had begun to formulate operational plans with tactical elements, albeit with shaky logistics.

Harper’s Weekly

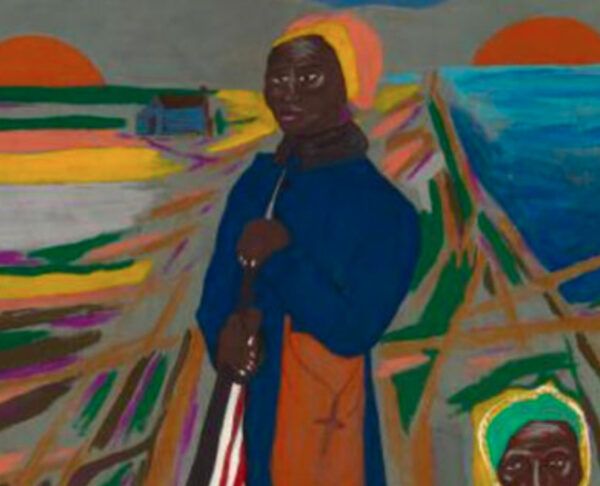

Harper’s WeeklyAfter the war, Lincoln’s secretaries John Nicolay and John Hay helped popularize the notion that the president had quickly mastered military strategy through deep study, but red flags abound in their narrative. Nicolay (left), Hay (center), and Lincoln depicted in a wartime illustration from Harper’s Weekly.

On November 1, Lincoln appointed McClellan general-in-chief, replacing Scott. Both Lincoln and McClellan agreed that the main Union military effort had to be focused in Virginia. But where? The president’s “Occoquan Plan,” which he presented to McClellan in early December, proposed sending half of the Potomac army against the Confederates at Centreville and Manassas while two smaller forces moved up the Occoquan River toward their rear. As historian Ethan Rafuse recognized, while the plan reflected McClellan’s earlier ideas, by then he had judged the enemy too strong to confront there. McClellan instead began conceptualizing a massive turning movement down the Virginia coast that would place his army between Manassas and Richmond. The latter would fall, and the war would end. But McClellan said nothing about this to the president, other than hinting at an East Tennessee campaign commanded by Sherman’s replacement, Major General Don Carlos Buell, a proposal that Lincoln liked. McClellan considered the talkative president a security risk.19

But no troops marched, and McClellan went to bed with typhoid fever just before Christmas. Radical Republicans on the newly established Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, a congressional oversight body, demanded that Lincoln fire the Democrat McClellan and bring back McDowell. The president reacted with a flurry of military activity designed to accommodate the Radicals. He wired his western commanders, Buell in Kentucky and Major General Henry Halleck (who had replaced Frémont) in Missouri, asking what McClellan’s plans were for them. They had no clue. When Lincoln and the cabinet received another earful from the Radicals, he fired off more telegrams to Buell, Halleck, and Ulysses S. Grant at Cairo, Illinois, pleading that they march into southern Kentucky and on to Tennessee in coordinated movements. Only Grant complied, with a limited demonstration up the Tennessee River into Kentucky that Halleck promptly recalled.20 “Delay is ruining us,” Lincoln wrote.21

Under such pressure to act, Lincoln began to study war even more intensively. On January 8, 1862, he checked out Halleck’s The Elements of Military Art and Science from the Library of Congress. Legend has it that Lincoln’s deep study—and quick mastery—of military literature that winter swiftly turned him into a war-making genius. Nicolay and Hay popularized the idea in their 1890 Lincoln biography. “He gave himself, night and day, to the study of the military situation,” they wrote. “He read a large number of strategical works. He pored over the reports from the various departments and districts of the field of war. He held long conferences with eminent generals and admirals, and astonished them by the extent of his special knowledge and the keen intelligence of his questions.”22

Lincoln’s self-education in military literature remains a cornerstone of evaluations of his conduct as commander in chief, and no wonder. Hay and Nicolay were the ultimate White House insiders. Yet red flags abound in their narrative. In addition to Hay and Nicolay, the only other eyewitnesses to describe such study by the president were their sometime assistant, William O. Stoddard, who made much the same claims in his 1885 and 1890 biographies of Lincoln, and Lincoln’s journalist friend Noah Brooks, who expected (with Mary Lincoln’s support) to replace Nicolay after the 1864 elections. Stoddard remembered “many books in the Executive business office…. They come and they go from this place and that. They litter the tables and they lean against the walls, and they look out from under the sofa, as if they were asking if their turn for consultation had come. Nobody knows when the President finds time for reading, but he does find it, somehow, between times and between days.”23

Nicolay and Hay’s precise wording deserves closer attention as well, as it is nothing less than a direct allusion to St. Luke’s biblical description of 12-year-old Jesus in the Temple. “And it came to pass,” Luke wrote, “that after three days they found him in the temple, sitting in the midst of the doctors, both hearing them, and asking them questions. And all that heard him were astonished at his understanding and answers.” Lincoln was more than a studious commander in chief according to Nicolay and Hay: He was another savior who “astonished” those around him with remarkable knowledge touched by divine genius.24

The notion of Lincoln’s intense study in a “large number of strategical works” further challenges what scholars otherwise know about his reading habits. Log-cabin legends aside, Lincoln was never a wide reader. He habitually read and returned to a few key books. He taught himself surveying from two standard texts. He enjoyed geometry so much that he slowly mastered Euclid. Lincoln’s law career began with reading a copy of William Blackstone’s standard Commentaries on the Laws of England over three years. As for pleasure reading, he turned repeatedly to newspapers and a few favorites, notably the Bible, Shakespeare, Robert Burns, and Lord Byron. During the war, he enjoyed Republican humorists Artemus Ward (Charles Farrar Browne), Orpheus C. Kerr (Robert Henry Newell), and Petroleum V. Nasby (David Ross Locke). Historian Robert Bray’s authoritative list of “what Lincoln read,” based upon Library of Congress circulation records and other sources, suggests that most of the books piled in Lincoln’s office as described by Stoddard must have been bound plays and poetry, along with some history, law, and reference books—not military treatises.25

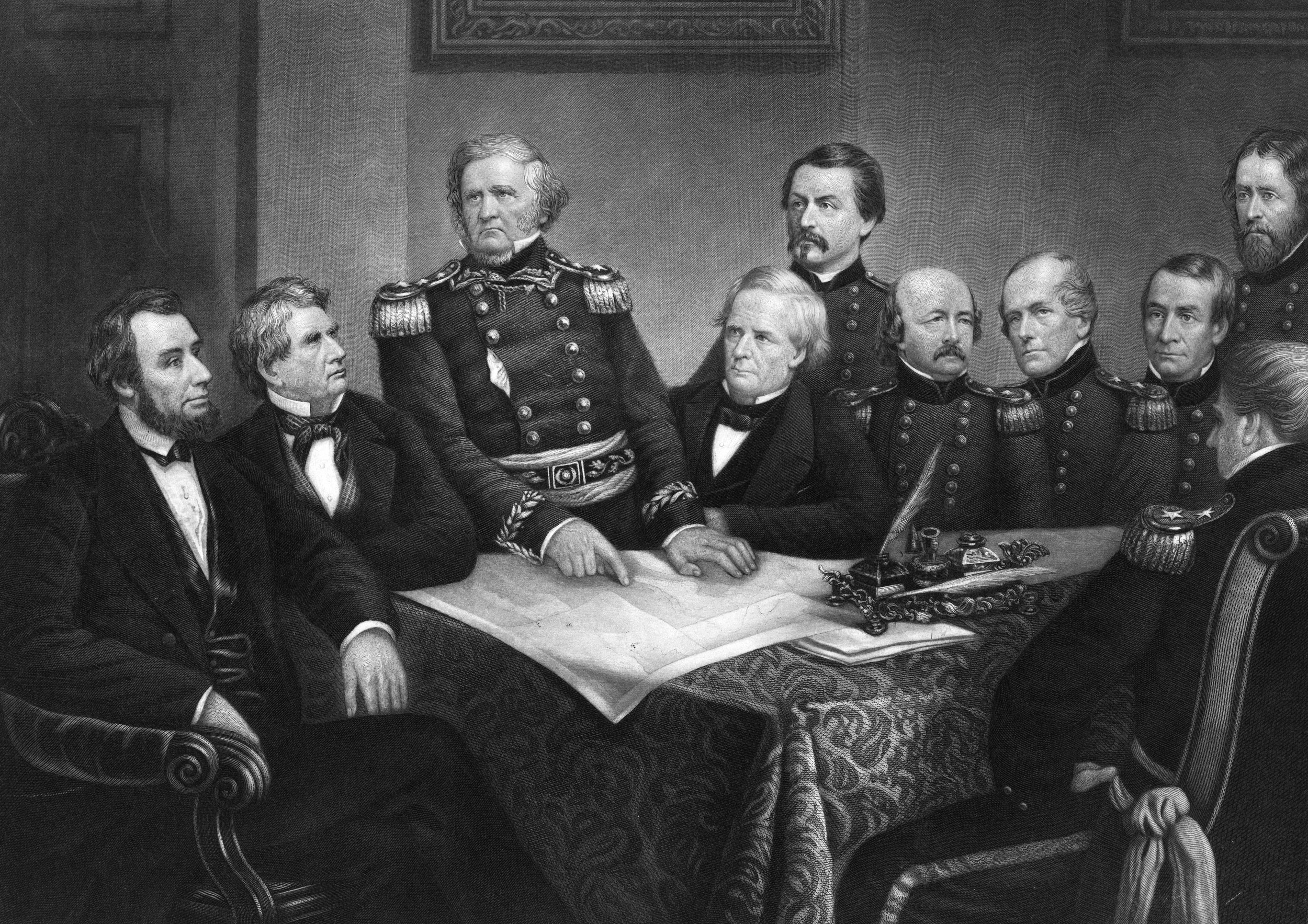

National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GalleryWinfield Scott points to a map as Lincoln, his top generals (including George McClellan, standing center), and cabinet members William Seward (seated next to Lincoln) and Simon Cameron look on in an illustration titled “Council of War in ’61.” After a slow start, Lincoln’s grasp of military basics began to take hold by 1862.

After Lincoln’s death, his former law partner William Herndon similarly recalled Lincoln saying, “I cannot read generally. I never read text books for I have no particular motive to drive and whip me to it. As I am constituted I don’t love to read generally, and as I do not love to read I feel no interest in what is thus read. I don’t, & can’t remember such reading.” But there was an exception. “When I have a particular case in hand I have that motive,” Lincoln added, “and feel an interest in the case—feel an interest in ferriting out the questions to the bottom—love to dig up the question by the roots and hold it up and dry it before the fires of the mind.”26 Even then, as historian David Donald admitted, Herndon did the lion’s share of their firm’s library research for citations and precedents.27

Still, did Lincoln “dig up” military theory while in the White House? Historian Carol Reardon makes a compelling case that he must have studied war, as his correspondence “reveals an increasing facility with the language and theoretical concepts of the professional soldier.” She adds, however, that we know almost nothing about what Lincoln read on the military arts except for the single book Bray identified as fitting the bill—the one book on the topic the president took from the Library of Congress, and the only volume that Stoddard identified by name—Halleck’s Elements.28

It was the obvious choice. Published in 1846 and revised in 1859, Elements had become the equivalent to Blackstone on law or Euclid on geometry, the one book that any would-be American military strategist had to master. In Elements, Halleck especially synthesized the ideas of his mentor, Dennis Hart Mahan, the West Point engineering professor and military theorist, and the Swiss officer Antoine-Henri Jomini as to the lessons of past wars, especially Napoleon’s. The 1859 edition also reflected more recent experiences in Mexico and the Crimea.29 The result, according to historian John Marszalek, became “essential reading for military men.”30

There simply remains no hard evidence that Lincoln read anything else on the topic. He did receive from the author, in June 1862, a free copy of Emil Schalk’s Summary of the Art of War, as Reardon has discussed. Schalk was an obscure German émigré and military theorist who lambasted McClellan in his later Campaigns of 1862 and 1863, in which he prioritized the destruction of enemy armies over seizing territory, just as Lincoln advocated. But as Reardon points out, that does not prove that Lincoln ever read Schalk. “Civil War historians frequently praise Abraham Lincoln’s foresight for urging Major General Joseph Hooker to make Lee’s army—and not Richmond—the objective of his Spring 1863 offensive,” Reardon observes, “but clearly the idea already had entered the public domain.”31

Lincoln kept Elements checked out for over two years, until mid-March 1864 and the ascension of Grant to overall command of Union forces. The president almost certainly read Halleck’s book. But Reardon is right. Lincoln already had started to grasp military basics by the time he began to read Elements. On January 10, 1862, only two days after he checked out the book and with McClellan still bedridden, Lincoln wandered into the office of Brigadier General Montgomery Meigs, the army’s quartermaster general. “General, what shall I do?” Lincoln pleaded. “The people are impatient; [Secretary of the Treasury Salmon] Chase has no money and tells me he can raise no more; the General of the Army has typhoid fever. The bottom is out of the tub. What shall I do?” Meigs was alarmed. Typhoid could keep McClellan out of action for weeks. Meigs advised Lincoln to meet with McClellan’s subordinates and decide who could command the Army of the Potomac in his absence.32

But who might that be? The Radicals still wanted McDowell, but he had lost the first major land battle of the war. Lincoln flirted briefly with a desperate idea. Attorney General Edward Bates had encouraged the president to take command of the army himself, although privately he did not think Lincoln was up to it.33 The day after meeting with Meigs, Lincoln informed his friend Browning that “he was thinking of taking the field himself, and suggested several plans of operation.” He even sketched out plans that reflected his growing determination to use superior Federal numbers against the enemy across the broad front, an approach that scholars later termed “concentration in time.” To overcome the Confederates’ ability to use interior lines to move elements of their smaller army to pressure points, Federal forces needed to “threaten all their positions at the same time with superior force, and if they weakened one to strengthen another seize and hold the one weakened &c.”34 But Lincoln did not invent the concept of concentration in time. For months, both Scott’s derided Anaconda Plan and McClellan’s grandiose plans in Virginia had advocated coordinated campaigns. Lincoln simply embraced it.35

In retrospect, the idea of Lincoln personally leading the main eastern Union army in January 1862 might seem little more than a cri de coeur—and most historians dismiss it as that—but it was not so far-fetched. Biographer Benjamin Thomas took Lincoln seriously, noting that he had as much, or more, military experience as many of the politicians upon whom he had bestowed generals’ stars. Still, Lincoln took Meigs’ advice and called a meeting with two of McClellan’s division commanders, McDowell and Brigadier General William B. Franklin.36 Lincoln—who, in his growing frustration with the general-in-chief, informed the two generals that “if General McClellan did not want to use the army, he would like to ‘borrow it’”—directed the pair to return the next morning with a plan of attack, in effect asking them to bypass McClellan’s authority, just as he had allowed McClellan to do with Scott.37 McDowell’s proposal looked much like Lincoln’s Occoquan Plan—“a remarkable fact,” according to Nicolay and Hay—while Franklin’s suggested turning movement via Chesapeake Bay reflected McClellan’s plans. Lincoln then called for a final session, asking the generals to consult with Meigs about the cost and time involved in Franklin’s proposal. The message was clear: Lincoln preferred his own ideas.38

On January 13, when Lincoln submitted to Buell and Halleck an outline of his new military “views,” concentration in time was spelled out in almost Euclidian essence. “I state my general idea of this war to be that we have the greater numbers,” he wrote, “and the enemy has the greater facility of concentrating forces upon points of collision; that we must fail, unless we can find some way of making our advantage an over-match for his; and that this can only be done by menacing him with superior forces at different points, at the same time; so that we can safely attack, one, or both, if he makes no change; and if he weakens one to strengthen the other, forbear to attack the strengthened one, but seize, and hold the weakened one, gaining so much.”39

That same day, the next scheduled meeting with Franklin and McDowell went off the rails when a partially recovered McClellan showed up. McClellan had arrived unexpectedly at the White House the previous day, and Lincoln had invited him to return and detail his war plans to the president and his cabinet. Now he would only affirm that he had a general plan and a timetable to make an offensive in Virginia—providing no specific details—and that he would make Buell move on East Tennessee. That was just enough to satisfy Lincoln, who was not yet ready to replace McClellan. In the end, Lincoln did not “borrow” the army and rarely spoke again about leading troops, except in a few frustrated asides about McClellan’s lack of haste in February and March, and again in frustration with the Federal pursuit after Gettysburg. Yet from mid-January 1862 on, Lincoln became a more assertive commander in chief with well-defined strategic and operational ideas. Using McClellan as a whetstone, Lincoln further refined his views on warmaking. They clashed repeatedly over McClellan’s preference for a turning movement into the Chesapeake Bay that became the failed Peninsula Campaign, as opposed to Lincoln’s advocacy of a straight-ahead assault south from the capital that would crush the enemy while keeping Washington safe. Lincoln went on to reroute troops promised to McClellan as he and new Secretary of War Edwin Stanton tried by telegram but failed to direct the destruction of Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s Army of the Valley in the Shenandoah.40

Lincoln and McClellan came to loggerheads again after the Battle of Second Manassas in August 1862, when Lincoln questioned the general’s patriotism, and the next month, after the Battle of Antietam, when McClellan failed to mount a timely pursuit of the withdrawing Army of Northern Virginia. Lincoln’s last attempt to get McClellan moving displayed the president’s matured operational thinking, grounded in Euclidian geometry. “Exclusive of the water-line, you are now nearer Richmond than the enemy is by the route that you can and he must take,” he wrote McClellan on October 13. “Why can you not reach there before him, unless you admit that he is more than your equal on a march? His route is the arc of a circle, while yours is the chord.”41 When McClellan did little in response, Lincoln finally fired him. “I saw how he could intercept the enemy on the way to Richmond,” he told Hay. “I determined to make that the test. If he let them get away I would remove him. He did so & I relieved him.’”42

Mary Livermore, a Chicago journalist and relief worker, arrived in Washington just days before Lincoln axed McClellan. “It was a gloomy time all over the country” she remembered. “[T]he fruitless undertakings and timid, dawdling policy of General McClellan had perplexed and discouraged all loyalists, and strengthened and made bold all traitors.” When Lincoln invited her and her associates to the White House, they readily accepted. What she saw shocked her. Lincoln’s “introverted look and his half-staggering gait” reminded her of “a man walking in sleep. He seemed literally bending under the weight of his burdens. A deeper gloom rested on his face than on that of any person I had ever seen.”

Lincoln’s mood matched his mien. When someone asked for “a word of encouragement,” the president refused. “The military situation is far from bright,” Livermore remembered him replying, “and the country knows it as well as I do.” Instead, he let off steam. “The fact is,” Livermore recorded Lincoln as saying, “the people haven’t yet made up their minds that we are at war with the South. They haven’t buckled down to the determination to fight this war through; for they have got the idea into their heads that we are going to get out of this fix, somehow, by strategy! That’s the word—strategy! General McClellan thinks he is going to whip the rebels by strategy; and the army has got the same notion. They have no idea that the war is to be carried on and put through by hard, tough fighting, that will hurt somebody; and no headway is going to be made while this delusion lasts.”43

What did Lincoln mean by the word “strategy?” For readers of Halleck’s Elements, strategy was “the art of directing masses on decisive points,” involving almost everything “beyond the range of each other’s cannon…. [It] regards the theatre of war, rather than the field of battle. It selects the important points in this theatre, and the lines of communication by which they may be reached; it forms the plan and arranges the general operations of a campaign.”44 Modern commanders would use the term “operations.” But Lincoln meant more than that. The greatest “strategic” model to emerge from the wars in Mexico and the Crimea was the turning movement. Frontal assaults traditionally meant heavy casualties. Skillfully planned maneuvers around an enemy’s flank and into its rear, in contrast, could minimize or even eliminate the need for battles, while forcing the enemy to surrender defensive positions or territory and retreat before being enveloped and captured. That was the “strategy” that McClellan had followed on the Peninsula.45

By then, however, Lincoln trusted his own military ideas more than those of his generals, whom he believed had failed by ignoring his insights. Clever “strategy” was out. He wanted “hard, tough fighting, that will hurt somebody.” Successful generals would protect Washington, win a war-decisive battle between there and Richmond, coordinate Federal campaigns east and west, and follow the chord instead of the arc. As it turned out, accomplishing that was easier said than done. While no longer an apprentice, Lincoln had still more to learn as the Confederates fell back toward Fredericksburg in the fall of 1862.

Kenneth W. Noe is Draughon Professor Emeritus of Southern History at Auburn University. He is the author or editor of nine books on the Civil War, including the forthcoming Abraham Lincoln and the Heroic Legend (LSU Press, 2026).

Notes

1. The number of works that suggest Lincoln was a military genius is too vast to list here. That is the subject of my forthcoming book, Abraham Lincoln and the Heroic Legend: Reconsidering Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief, to be published by Louisiana State University Press.

2. Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ, 1953), 4: 157–160, 162 (hereafter cited as CW).

3. CW, 4: 157–160, 162, 164, 176, 183, 191–246, 249-71; John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln: A History (New York, 1890), 3: 321–323; Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln (Baltimore, 2008), 2: 2, 4–5, 8, 18, 30–31, 36, 40, 45–49, 65–66.

4. CW, 4: 279–280, 284–285; Howard K. Beale, ed., The Diary of Edward Bates, 1859–1866 (Washington, 1933), 177-80; Michael Burlingame, ed. With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860–1865 (Carbondale, IL, 2000), 46–47; Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay (Carbondale, IL, 1997), 5; Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 3: 375-95, 4: 288–290, 301–302; Theodore Calvin Pease and James G. Randall, eds., Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library, v. 20, Lincoln Series, vol. 2, The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, v.1, 1850–1864 (Springfield, IL, 1925); 476, 563; Edgar T. Welles, ed., Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson, Vol. 1: 1861-March 30, 1864 (Boston, 1911), 6–16, 47–48.

5. CW, 4: 177–178, 273; William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Abraham Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life (New York, 1892), 2: 319; Lesley J. Gordon, “‘Novices in Warfare’: Elmer E. Ellsworth and Militia Reform on the Eve of the Civil War,” Journal of the Civil War Era 11 (June 2021): 194–215; Lesley J. Gordon, “The Zouave,” The Civil War Monitor 14 (Fall 2024): 48–53, 57, 68; Meg Groeling, First Fallen: The Life of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the North’s First Civil War Hero (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2021), 1–212: David S. Reynolds, Abe: Abraham Lincoln in His Times (New York, 2020), 528–532.

6. CW, 4: 313–316; Beale, ed., Diary of Bates, 180; “General M.C. Meigs on the Conduct of the Civil War,” American Historical Review 26 (January 1921): 287–288, 299–302; Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 3: 434-41; Admiral [David Dixon] Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War (New York, 1885), 13–23.

7. Pease and Randall, eds., Diary of Browning, 1: 476.

8. Burlingame and Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White House, 11.

9. “Meigs on the Conduct of the Civil War,” 289–290; Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 4: 298–300, 303; Stephen W. Sears, ed., The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860–1865 (New York, 1989), 12–13; Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln, 2: 176; Ethan S. Rafuse, McClellan’s War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union (Bloomington, IN, 2005), 2–7, 96–98; Donald Stoker, The Grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War (New York, 2010), 36–37; T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and His Generals (New York, 1952; reprint, New York, 2000), 19–22.

10. Pease and Randall, eds, Diary of Browning, 1: 481; “Meigs on the Conduct of the Civil War,” 289–290; Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 4: 303, 321–23.

11. Williams, Lincoln and His Generals, 20.

12. Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 4: 352-56, 358–359.

13. CW, 4: 457–458, 460, 463, 468–469.

14. Francis V. Greene, “Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief,” Scribner’s Magazine 46 (July 1909): 106. Greene was the son of Brigadier General George Sears Greene of Gettysburg fame.

15. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series I, vol. 5, 6–8 (hereafter cited as OR); Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 4: 338–340; Sears, ed. Papers of McClellan, 28–30, 67, 70–75.

16. Stoker, The Grand Design, 63.

17. William Howard Russell, My Diary North and South, ed. by Eugene H. Berwanger (New York, 1988), 317–318. Since a “navvy” was an unskilled laborer on an engineering project, such as a canal or railroad, the condescending Russell essentially was describing Lincoln as someone from the lower classes. Note that William E. Gienapp, in Abraham Lincoln and Civil War America (Oxford, 2002), 87, dates this event to the period immediately after First Manassas.

18. CW, 4: 497; 544-45; Burlingame and Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White House, 29; Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 5: 60–64.

19. Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 4: 466–469, 5: 91-92, 99–100, 149–152.

20. OR, Series I, vol. 7, 530–535, 537–538, 545–546; Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 5: 69–74, 91–92, 98–100; John Niven, ed., The Salmon P. Chase Papers, Vol. 1, Journals, 1829-1872 (Kent, OH, 1994), 321–322; Sears, ed., Papers of McClellan, 147–150.

21. OR, Series I, vol. 7, 535.

22. Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 5: 155–156; Carol Reardon, With a Sword in One Hand & Jomini in the Other: The Problem of Military Thought in the Civil War North (Chapel Hill, 2012), 28.

23. William O. Stoddard, Abraham Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life. Showing the Inner Growth, Special Training, and Peculiar Fitness of the Man for His Work (New York, 1885), 245; William O. Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times (New York, 1890), 151–152; Noah Brooks, Abraham Lincoln and the Downfall of American Slavery (New York, 1888; new ed., 1894), 326–327.

24. Luke 2:46-47, King James Version.

25. Robert Bray, Reading with Lincoln (Carbondale, 2010), see esp. ix-x, 4, 10–13, 16–20, 28–29, 35, 41–42, 46–49, 69–80, 82–84, 87–118, 140–150, 168–170, 189–190, 194, 200–215; Robert Bray, “What Abraham Lincoln Read—An Evaluative and Annotated List,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 28 (Summer 2007): 28–81. Bray’s list of “what Lincoln read” suggests that he had on hand perhaps 50 books in the White House during his four-year term, an admittedly hefty number, with 21 taken from the Library of Congress. Bray warns, however, that it is impossible now to determine what books were read by Lincoln, his wife, sons, or secretaries.

26. William H. Herndon, “Analysis of the Character of Abraham Lincoln: A Lecture by William H. Herndon,” Abraham Lincoln Quarterly 1 (December 1941): 431.

27. David Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon (New York, 1948), 36–38.

28. Reardon, With a Sword in One Hand, 28; Bray, “What Abraham Lincoln Read,” 28–81; Stoddard, Inside the White House, 152.

29. H. Wager Halleck, Elements of Military Art and Science or, Course of Instruction in Strategy, Fortification, Tactics of Battles, &c., Embracing the Duties of Staff, Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery, and Engineers. Adapted to the Use of Volunteers and Militia (Boston, 1846); John F. Marszalek, Commander of All Lincoln’s Armies: A Life of Henry W. Halleck (Cambridge, 2004), 36–47, 98, 114, 125, 167.

30. Marszalek, Commander of All Lincoln’s Armies, 44, 46.

31. Reardon, With a Sword in One Hand, 32–40.

32. “Meigs on the Conduct of the Civil War,” 292; David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York, 1995), 355; Williams, Lincoln and His Generals, 257.

33. Beale, ed., Diary of Bates, 218–219, 220, 223–226.

34. Pease and Randall, eds., Diary of Browning, 1: 523.

35. OR, Series I, vol. 5, 9–11; CW, 4: 457-58, 544-45; Stoker, Grand Design, 36–43, 55–59; Williams, Lincoln and His Generals, 19–23, 27–33, 48. Stoker best makes the case about Lincoln not inventing Concentration in Time.

36. “Memorandum of General McDowell,” 772–774, in Henry J. Raymond, The Life and Public Services of Abraham Lincoln, Sixteenth President of the United States (New York, 1865); Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (New York, 1952), 291–292.

37. “Memorandum of General McDowell,” 773.

38. Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 5: 156–169.

39. CW, 5: 98-99.

40. CW, 6: 327–329; Nicolay and Hay, Abraham Lincoln, 5: 157–158; “Meigs on the Conduct of the War,” 292–293; Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln, 2: 220–221, 295; Donald, Lincoln, 330; William Marvel, Lincoln’s Autocrat: The Life of Edwin Stanton (Chapel Hill, 2015), 151–152, 153–155; Stoker, Grand Design, 54, 77–78; Williams, Lincoln and His Generals, 55–58.

41. OR, Series I, vol. 19, pt. 1, 13–14.

42. Burlingame and Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White House, 232.

43. Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War (Hartford, 1889), 554–561; Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, compilers and eds., Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln (Stanford, CA, 1996), 210, 300–302, suspected that Livermore’s account contains “a good deal of literary invention” and was doubtful as a true account, yet admitted that similar accounts existed, notably from Hay. Most scholars credit Livermore at least to a degree.

44. Halleck, Elements, 35–60; Fehrenbacher and Fehrenbacher, Recollected Words, 210, 300–302.

45. Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones, How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War (Urbana, IL, 1991),11–17.

Related topics: Abraham Lincoln