Library of Congress

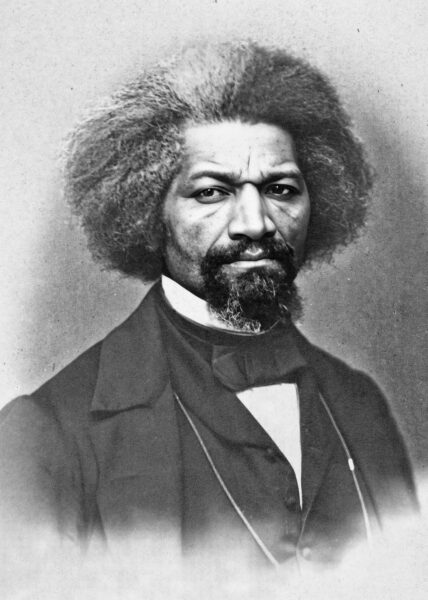

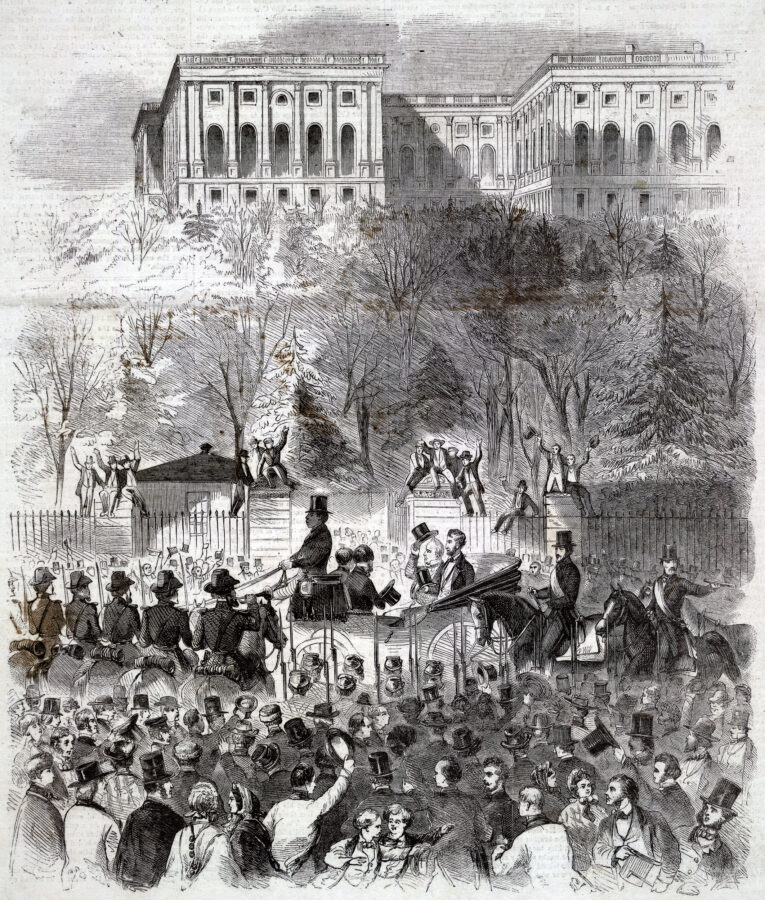

Library of CongressPeople crowd the grounds of the U.S. Capitol’s East Portico to witness the inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln on March 4, 1861.

Over the first few days of March 1861, the weather in Washington, D.C., turned deceptively warm, up to the low 70s, and the iron hand of winter appeared to have lost its grip, raising hopes for an early spring. But things in Washington are never quite what they seem. In the early morning hours of March 4, the temperature dropped 30 degrees and took the city’s citizens by surprise. The early thaw had been nothing more than a tease. Trees were still bare, the earth still hard in places, the streets dry and dusty. The entire city looked and felt in disarray.

On that day, which began with overcast skies and a chill wind that drove away the March thaw, John Hay couldn’t decide if he liked or detested the nation’s capital. A dapper young man of 22 who always dressed to the nines, but whose boyish face and gleaming dark eyes made observers think he looked like a teenager, he did marvel at the city’s broad avenues and the stupendous view of the surrounding countryside gained by climbing the iron tiers of the Capitol’s unfinished dome. But for Hay, the city only escaped “squalor by a hair’s breadth.” Charles Dickens had agreed wholeheartedly. In 1842, when the British novelist visited America’s capital, he named it “the City of Magnificent Intentions,” failing to understand its “spacious avenues, that begin in nothing, and lead nowhere.” Dickens also mentioned that the place was “very unhealthy” and that occasionally a “tornado of wind and dust” could be seen drifting its way down the streets to nowhere.1

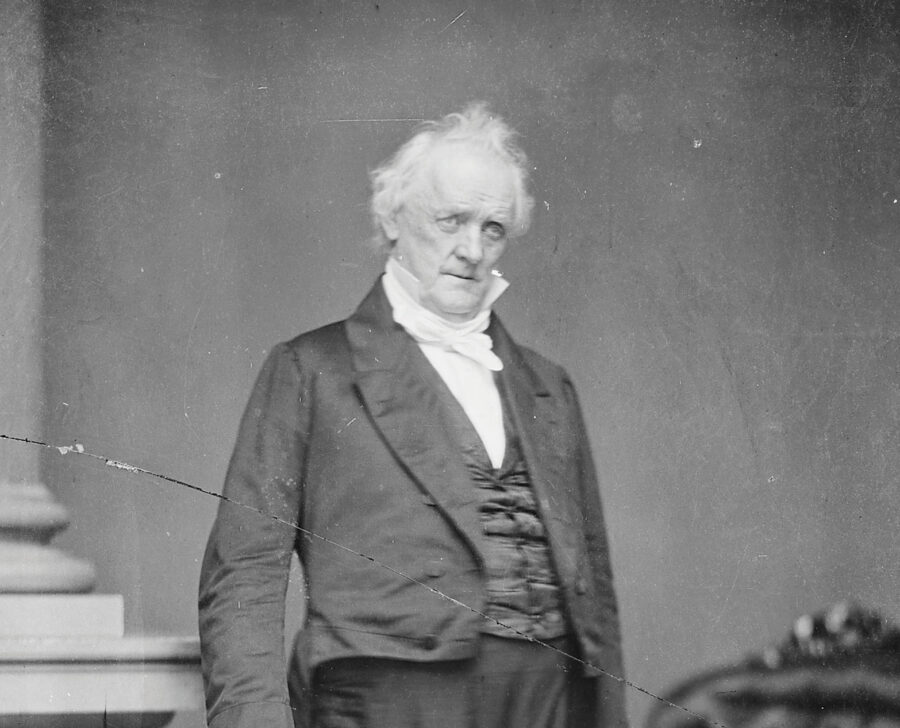

National Archives

National ArchivesOn the day of Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, President James Buchanan (above) was in the Capitol endorsing bills “until after his term of office had expired,” causing him to be late to pick up his successor and accompany him to the ceremony.

Throughout this morning in 1861, the lawyer from Illinois on whose campaign Hay had worked waited patiently in Parlor Six of Willard’s Hotel to be picked up. Then he and President James Buchanan would ride together to the Capitol’s East Portico, where Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration would take place at noon. Buchanan was late. His tardiness did not help Lincoln’s nerves. According to the New York Herald, Buchanan was at the Capitol, where he kept endorsing bills “until after his term of office had expired” (but actually the congressional clock was turned back to make his signatures “legal”).2 When he was finished signing, he returned to the Executive Mansion, where an extravagant, open barouche, accompanied by livery and drawn by two horses, stood ready for him. He was taking his time.

In due course, Buchanan’s barouche pulled up to the ladies’ entrance of Willard’s on Fourteenth Street. As the crowd offered him polite applause, the president alighted gracefully and walked into the hotel. Although splendidly dressed, with stiff upturned paper collars hiding his neck, Buchanan always seemed a little off-kilter to observers. His head, covered by a “low-crowned, broad-brimmed silk hat,” was permanently tilted to the left.3 This was caused by a medical condition called “wryneck” (torticollis), which may have resulted from an unusual eye affliction: One of Buchanan’s brilliant blue eyes was nearsighted, the other farsighted, and his left eye socket was higher than the right one. He had learned early on to accommodate his optical problems by tipping his head toward his left shoulder and closing one of his eyes.

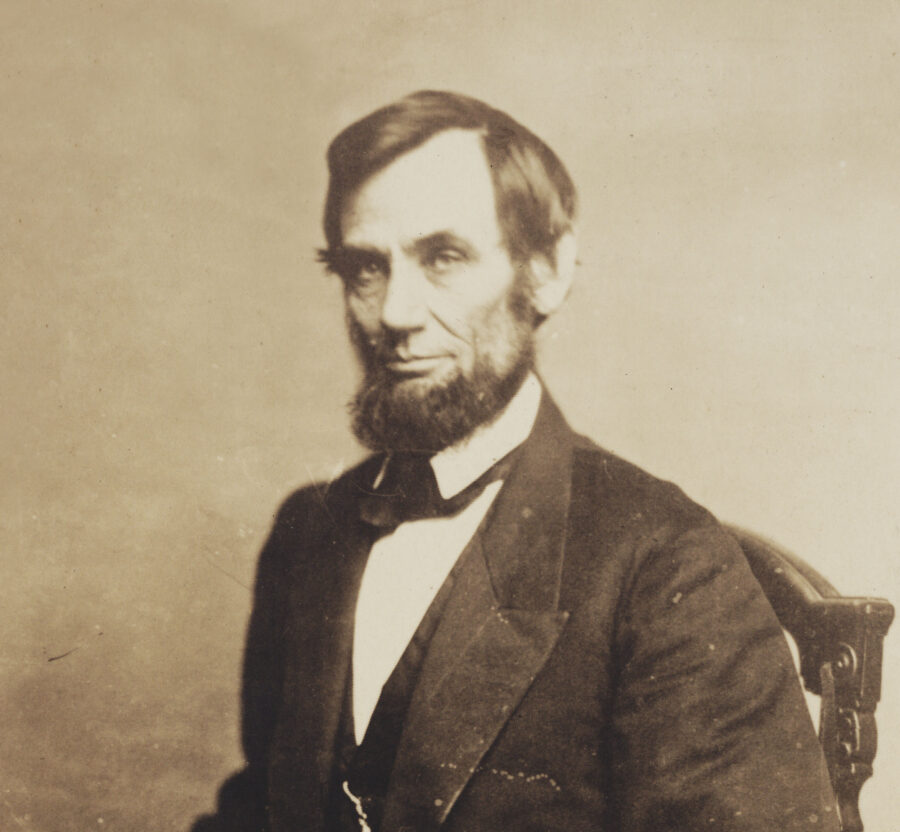

Library of Congress

Library of CongressLincoln as he appeared in May 1861.

For those in the crowd seeing Lincoln for the first time, his looks were sharp and striking. “His face,” wrote one news reporter, “though not handsome, has a pleasant and intelligent expression, and the reason for the ugliness of some of his portraits is, as he facetiously alleges, because they are ‘devoid of his accustomed grace.’” But William H. Herndon, Lincoln’s loyal and admiring law partner in Springfield, Illinois, supplied a lengthy and splendid description of him that suffered only in its redundancy: “Abraham Lincoln was about six feet four inches high…. He was thin—tall—wirey—sinewy, grisly—raw boned man, thin through the breast to the back—and narrow across the shoulders, standing he leaned forward—was what may be called stoop shouldered, inclining to the consumptive by build. His usual weight was about 160 pounds…. He was a sad looking man: his melancholy dript from him as he walked.”4

The barouche carrying the two men jostled forward and turned onto Pennsylvania Avenue, where it joined a long procession on its way to the Capitol. Along the avenue, there was an eerie silence, broken only by the clopping of horses’ hooves and the pounding of marching feet. From the carriage, Lincoln and Buchanan occasionally doffed their silk hats, but said little or nothing to one another. One of the mounted guards riding beside them noticed that Buchanan looked nervous, “trembling as if to his execution.” With greater generosity, Ward Hill Lamon, a lawyer from Illinois who had appointed himself Lincoln’s personal bodyguard, commented that “Buchanan’s manner was as usual grave, thoughtful and dignified, silent and uncommunicative.” Breaking the eerie silence along the sidewalks, a shout came from the upper floor of a building along Constitution Avenue, a woman’s voice sounding sympathy with the South: “There goes that black Republican ape!” More soberly, another spectator, Margaret McLean, remarked that the carriage “might be said to contain the destiny of the United States.”5

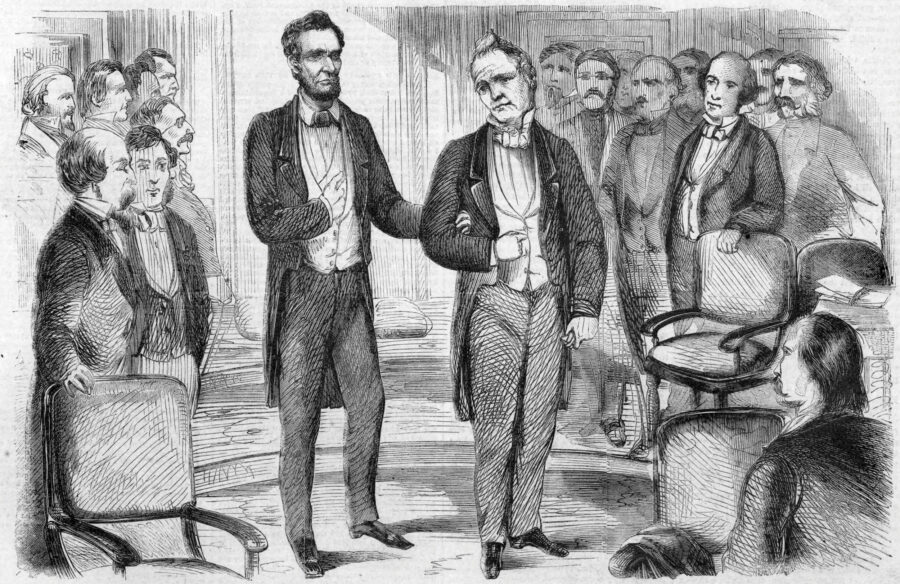

Harper’s Weekly

Harper’s WeeklyIn this Harper’s Weekly illustration of the inaugural procession, Lincoln and Buchanan ride in an elaborate barouche en route to the Capitol. One of the mounted guards riding beside them noticed that Buchanan looked nervous, “trembling as if to his execution.

Lincoln’s inaugural address, written and revised over the previous two months, rested in his coat pocket. Help in crafting the speech had come from trusted advisers, including David Davis, Orville H. Browning, Frances P. Blair Sr., and Carl Schurz. William H. Seward, the senator from New York whom Lincoln had appointed secretary of state, recommended the most useful changes, although Lincoln adopted only about half of them, often putting his former rival’s ideas into his own words. Seward’s deletions and emendations calmed the language of the speech and its overall message, especially those directed toward southerners and the various factions of the Republican Party.

On the rooftops along Pennsylvania Avenue, armed guards in uniform stood ready to shoot any intruder who might assault the coach. The recent secession of seven Deep South states and the current siege of Fort Sumter spread tension and fear throughout Washington, not only over the fate of the Union but also over the possibility that southern interests might try to disrupt the inauguration or attempt to kidnap or assassinate Lincoln. Shortly after his election, he had received a frightening letter. Calling himself Vindex, the writer declared: “Caeser had his Brutus! Charles the First his Cromwell[.] And the President may profit by their example. From one of a sworn Band of 10 who have resolved to shoot you from the south side of the Avenue in the inaugural procession—on the 4th of March 1861.” Another letter warned Lincoln that southerners would kill him if his inauguration went forward. The president-elect had only two choices: “death or resignation.”6 To make sure no serious mishap occurred that day, Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, with his rather addled inspector general of the district, Colonel Charles P. Stone, made careful deployments of armed fire companies, police, city militia volunteers, some engineers from the regular army, and a few cavalry companies along the mile from Willard’s to the Capitol. Stone took his duties very seriously. He was not the only one to feel the tension in the air. Almost 50 years after the event, Charles Francis Adams Jr., the grandson and great-grandson of presidents, remembered “a curious sense of uneasiness [that] prevailed—a sort of nervous expectancy.”7

Harper’s Weekly

Harper’s WeeklyLincoln and Buchanan walk arm-in-arm into the Senate chamber before the inauguration.

At last the barouche pulled up to the north door of the Capitol. Already the crowd on the hilltop, mostly men but with a scattering of women, was thick and impatient. Lincoln and Buchanan entered the temple of liberty arm-in-arm and walked to the Senate chamber, its gallery filled to the brim with spectators. There they witnessed the inauguration of Hannibal Hamlin as vice president. After that brief ceremony, Buchanan and his successor were led to the ornately designed President’s Room, where they waited, both men looking uneasy and uncomfortable.

Hay stood near them. He tilted his head in the direction of Buchanan and Lincoln because he anticipated that there would be “a certain significance in the conversation” between them, “between the petty past and the great future.” But his boyish wonder went unfulfilled. Casually Buchanan faced Lincoln and said: “I think you will find the water of the right-hand well at the White-House better than that at the left,” and then described sundry aspects of the kitchen and the pantry. Lincoln, said Hay, “listened with that weary, introverted look of his, not answering.” While Buchanan spoke trivialities to Lincoln, the president-elect’s youngest son, Thomas (“Tad”), lay down on the floor and, according to another witness, began “kicking his feet up against one of the great marble pillars and calling out with good lungs ‘I want my Paw, I want my Paw.’”8 Despite these banalities, the procession of dignitaries lined up and walked solemnly through a temporary wooden passageway that led to a clapboarded platform that had been erected over the main steps of the East Portico.

Mary Todd Lincoln, who had earlier been escorted to the Capitol, sat in the front row on the platform with Tad and his brother Willie. She had slept fitfully the night before. A large retinue of the Todd family sat near Mrs. Lincoln, whose eldest son, Robert, 17, along with Hay and his fellow secretary John G. Nicolay, occupied seats closer to the rectangular wooden canopy erected to shelter the president-elect from rain. Nearby waited Edward D. Baker, Lincoln’s old friend from Illinois and now senator from Oregon. In full view of the crowd below, Stephen A. Douglas, the short, bombastic Illinoisan who had beaten Lincoln in the race for the Senate in 1858 only to lose to him in the presidential election of 1860, remained silent and calm in anticipation of the pageantry that was about to begin. On the platform, it took time for everyone to take their seats and settle down.

National Archives (Barton); Library of Congress

National Archives (Barton); Library of CongressEdward D. Baker (left) and Clara Barton

A short distance away sat Roger B. Taney, chief justice of the United States, and the justices of the Supreme Court, all sharing the same expression of disinterest that judges worked so assiduously to achieve at public events. Wrinkled and worn, Taney, 84, appeared to be at death’s door. A reporter described him as “old, shriveled to the bone, with a face like parchment, muffled in his silken robes.” In his scrawny hands, Taney clenched the Bible he would use to administer the oath of office. Next to him sat Lincoln, looking “pale, and wan, and anxious.”9 No doubt Taney lacked any enthusiasm for reciting the oath of office to the man who had remorselessly condemned the chief justice’s majority opinion in the notorious case of Dred Scott v. Sandford.10

At last, Senator Baker stood at the podium and announced plainly, “Fellow Citizens: I introduce to you Abraham Lincoln, the President-elect of the United States.” As Lincoln stood up, the crowd greeted him “with prolonged cheers.” He stepped to the podium and suddenly realized that he needed to sort himself out. First, he used his cane to hold down the pages of his address in the stiff breeze. Then he fumbled with his tall stovepipe hat, nervously exchanging it from hand to hand. Douglas saw his opponent’s dilemma and gallantly offered a hand, saying “Permit me, sir.”11 He held the hat in his lap throughout the speech. Meanwhile, Lincoln searched for his reading glasses and awkwardly retrieved them from a pocket, unfolding them in an elaborate fashion, like a magician making a feeble attempt at sleight of hand. Finally, spectacles in place, he began reading his address “in a loud, clear voice”: “Fellow citizens of the United States.”

As these opening words rang out, it appeared to at least one observer in the audience that Lincoln “loomed and grew, and was ugly no longer.” Seated not far away from the podium was 15-year-old Robert B. Stanton, who recalled that Lincoln “spoke so naturally, without any attempted oratorical effect, but with such an earnest simplicity and firmness, that he seemed to me to have but one desire as shown in his manner of speaking—to draw that crowd close to him and talk to them as man to man.” Clara Barton, then a clerk in the U.S. Patent Office, praised Lincoln for his “loud, fine voice, which was audible to many, or a majority of the assemblage.” Even as he spoke, people in the crowd remarked that they “didn’t know he wore glasses” or shouted out, “Take off them spectacles, we want to see your eyes.”12

Library of Congress

Library of Congress When it was time to deliver his inaugural address, a visibly anxious Lincoln approached the podium, fumbling with his stovepipe hat and awkwardly retrieving his reading glasses from a pocket. As he did so, the assembled crowd (shown above) greeted him “with prolonged cheers.”

At first, Lincoln spoke slowly and deliberately, as he often did in his public addresses, waiting for his words to fall into a pattern and rhythm as he warmed to the occasion. Any nervousness he may have felt disappeared, and he looked cheerful, composed, and relaxed as he continued reading from the marked-up page proofs in his hand. His country drawl marred his elocution, but he spoke carefully enough and moderated his tone to such a degree that easterners had no difficulty understanding what he was saying. After years of experience delivering political speeches, particularly over the past decade, Lincoln had mastered the skill of projection. His high tenor voice, which some listeners described as shrill, carried a vast distance—so much so, in fact, that Adams, reporting for the Boston Evening Transcript, wondered if he might not have “the lungs of Stentor.”13 Even so, Lincoln was not a brilliant orator—not like his political idol Henry Clay, or the thunderous Daniel Webster. He wrote his speeches relying on plain style and plain words.

As he spoke, a few clouds parted above the Capitol and a ray of sunshine flooded the East Portico in bright, almost searing light. Ward Hill Lamon knew that his friend would not have an easy time satisfying multiple interests in a single speech: “To moderate the passions of his own partisans, to conciliate his opponents in the North, and divide and weaken his enemies in the South, was a task that no mere politician was likely to perform, yet one which none but the most expert of politicians and wisest of statesmen was fitted to understand. It required moral as well as intellectual qualities of the highest order.” He used his head to draw attention to his words, “throwing or jerking or moving it now here and now there—now in this position, and now in that, in order to be more emphatic—to drive the idea home.” As Lincoln fell into his comfortable patterns of speech, his voice—still sailing over large crowds—“became harmonious, melodious—musical.” His grey eyes “would flash fire.”14

By focusing first on the national crisis, Lincoln reassured southerners and northerners alike that all the available evidence, including “nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you,” pointed to the policy of him and his majority party to halt the spread of slavery into the western territories without interfering with slavery where it already existed in 15 of the nation’s 34 states.15 In that regard, he called for the fair enforcement of “all those acts which stand unrepealed, than to violate any of them.” But purposeful enforcement of the law, including controversial ones like the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, would become impossible if the Union was cast asunder. He wanted those who would destroy the Union and everyone else to understand: “I hold, that in contemplation of universal law, and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual.” In his view, the Union remained unbroken, and it was his “simple duty” to enforce faithfully the nation’s laws. Despite his resolve to do that duty, he said with less heat, “there needs to be no bloodshed or violence; and there shall be none, unless it be forced upon the national authority.” Yet he wanted it clearly understood that he would use his authority as chief executive “to hold, occupy, and possess the property, and places belonging to the government, and to collect the [federal] duties and imposts.” In doing so, he vowed not to let Fort Pickens in Pensacola Bay and Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor fall into Confederate hands.

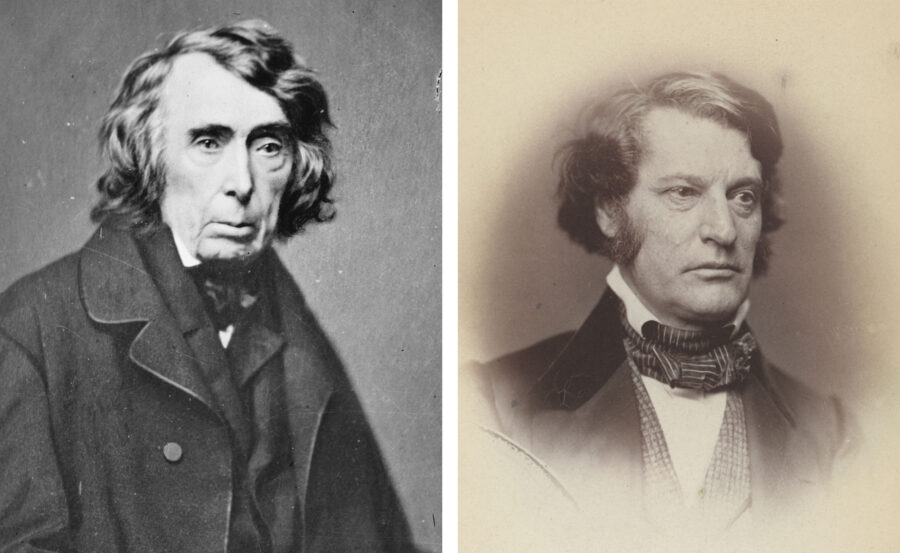

Library of Congress

Library of CongressRoger B. Taney (left) and Charles Sumner

Next he turned his attention not to the southern secessionists (in an earlier draft he wanted to call them traitors) but to “those … who truly love the Union.” Warning them of the dangers of disunion and “the destruction of our national fabric, with all its benefits, its memories, and its hopes,” he spoke of the possibility that a decision in favor of secession might saddle them with more woes than the ones they faced by remaining in the Union. “Physically speaking,” he said, “we cannot separate.” Pragmatically, he rightly pointed out that “we cannot remove our respective sections from each other, or build an impassable wall between them.”

But then, rather swiftly, Lincoln’s tone changed. Directing his concluding words toward hotheaded and intransigent southerners more than anyone else, he made in the penultimate paragraph this bold declaration: “In your hands, my dissatisfied countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict, without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to ‘preserve, protect and defend’ it.”16 That was not all. In concluding, Lincoln altered his tone once more, this time to an avuncular one meant to sooth all of his countrymen, North and South. Echoing Thomas Jefferson’s first inaugural address, Lincoln pleaded with his fellow Americans to recognize that “we are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies.” What followed became the most famous passage of the address: “Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as they surely will be, by the better angels of our nature.”17 It had taken him only 35 minutes to address the nation.

All during the speech, various people in the crowd heckled Lincoln with loud shouts of “That won’t do”; “Never, never”; “Worse than I expected”; “Too late!”; “We defy your threats”; and “We are for Jeff Davis.” One of Lincoln’s Republican supporters, James W. Nye, tried to drown out the naysayers by sparking applause among the onlookers. For the final two paragraphs of the address, however, the crowd listened “in hushed expectancy.” At the close, Lincoln received a long and loud ovation. Meanwhile, the denunciations against him resumed, but Nye stood on a stretch of a small ridgeline and “shaking his fist at the noisiest band of secessionists near by, shouted, ‘Now you’ve heard the truth for once in your lives, you damned traitors! That’s the best speech that’s been delivered since Christ’s Sermon on the Mound [sic].’”18

Amid the plaudits and epithets, Lincoln faced Taney to take the oath of office. Taney, looking nervous, rose unsteadily from his chair, fumbled a bit with the heavy Bible, and held it out to Lincoln. The president-elect placed one hand on the Bible and raised the other. In a voice barely audible, Taney spoke the words Lincoln was required to repeat. Lincoln did so loud enough for everyone to hear: “I, Abraham Lincoln, do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.”19 Long, tall Abe Lincoln bowed toward the Bible and, with noticeable solemnity, kissed it.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressOn the night of the inauguration, Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, joined a myriad of well-wishers in a specially constructed building behind City Hall for the inaugural ball—an event shunned by southerners in Washington. Above: Harper’s Weekly published this illustration of some of the “superb costumes” worn by the “distinguished ladies present” at the ball.

In an instant, more cheers and applause spread across the Capitol grounds, General Scott’s battery of guns boomed a reverberating salute to the new president, and the Marine Band struck up “God Save Our President.”20 Soon the wooden platform emptied of guests and spectators as Lincoln and Buchanan once more occupied their seats in the barouche, which joined the planned procession from the Capitol to the White House. Walking home, Adams encountered Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, a Republican abolitionist, who wondered about the speech, if: “Lincoln had it in his mind, if indeed he ever heard of it; but the inaugural seems to me best described by Napoleon’s simile of ‘a hand of iron and a velvet glove.’”21 Hundreds of miles away, in drought-ridden Kansas, a woman revealed little interest in the content of the address, but wrote to her sister what many people in the free states must have been thinking: “The inaugural address arrived in town today. So Lincoln did not get killed up to that time—Do you believe any will dare take his life[?]”22

On the White House steps, Buchanan, eager to make a quick getaway, leaned toward Lincoln and said gleefully: “If you are as happy, my dear sir, on entering this house as I am in leaving it and returning home, you are the happiest man in this country!” Inside, Lincoln was led to a reception room where about 500 citizens lined up to shake his hand. He looked “in excellent spirits, and gave each of his friends a cordial grasp and smile.” One young woman described Mrs. Lincoln as “a plain good sort of a woman, nothing elegant in her manners—rather short.”23 Ladies in Washington society, however, looked down their noses at the president’s wife, seeing her as a frontier woman who lacked cosmopolitan refinements.

Southern women in the nation’s capital shunned Mrs. Lincoln and refused to attend an invitational inaugural ball that evening, held in a building behind City Hall that had been constructed for the occasion. Inside, a huge tent, vaingloriously called the “white muslin palace of Aladdin,” decorated the walls and ceiling with shimmering fabric made of cotton and festooned with evergreens. The absence of southern gentlemen and ladies took luster and verve out of the evening, if only because the cavaliers and belles always danced with such light-footed precision and flair. Lincoln had asked Buchanan, in a written invitation, would he not “join us in attending the Inauguration Ball this evening.”24 Buchanan made no reply and no appearance.

Fashionably late, the Lincolns arrived at the ball to applause and cheers. Mrs. Lincoln looked resplendent in a gown of shimmering blue silk with a blue feather in her hair, and for the rest of the night she danced waltzes and polkas with a smoothness and grace that belied the sneers of the Washington social set. Her tired husband, who disliked dancing, felt out of place. After an hour or two at the ball, Lincoln—having had his fill of fulsome well-wishers, bowing diplomats, and overbearing office seekers—went home around midnight, but not to sleep.

As he entered the Executive Mansion, Nicolay handed him an urgent letter from Major Robert Anderson, the commander of the besieged garrison at Fort Sumter. Lincoln summarized the letter in his own words: Anderson wrote that his soldiers’ “provisions would be exhausted before an expedition could be sent to their relief.”25 Ten blocks away, in Aladdin’s palace, the music played on into the early morning as the guests slid wearily along the dance floor, their dull silhouettes moving like ghostly shadows across the walls covered with finely woven cotton. If this great ceremonial Union Ball brought forth any recollection of the one—described in so many history books of the time—held by the Duchess of Richmond three days before the Battle of Waterloo, no one bothered to mention it.

It is perhaps a little too easy to say that the reactions to Lincoln’s inaugural address around the country (and in the seceded states) were predictable. In point of fact, they disclosed such a wide range of perspectives and speculations that no simple generalizations about the reception of the speech can be made. Some northerners (especially Republicans) spoke highly of the speech; others (especially Democrats) denounced it. Southerners in the Deep South heard in Lincoln’s words a call for war, while others, including those in the slave states that remained in the Union, found a tone of moderation in those same words. Among black Americans in the North, Lincoln’s speech left them in despair. The new president’s concentration on the Fugitive Slave Law and his insistence that the Republican Party only opposed the extension of slavery, not the existence of it, left blacks disappointed and angry with him. One black editorialist lamented that he and his fellow African Americans could “gather no comfort from the Inaugural.” Never one to stifle his opinion, Frederick Douglass openly conveyed his disgust with Lincoln’s speech. Reading it, he said, “has left no very hopeful impression upon our mind for the cause of our down-trodden and heart-broken [black] countrymen. Mr. Lincoln has avowed himself ready to catch them if they run away, to shoot them down if they rise against their oppressors, and to prohibit the Federal Government irrevocably from interfering for their deliverance.”26

In the South, the cries and demands for war inundated the region. Spitting with hatred and scorn, Sue Sparks Keitt, the wife of U.S. Representative Laurence Massillon Keitt of South Carolina, a famous fire-eater, blamed Lincoln and the Republicans for the war that would surely come. “Let it be [war],” she wrote to her northern friend, “if war they desire. And the Stars and Stripes will shame their ancient glories when the ‘Southern Cross’ takes the field.” Southern Unionists, however, interpreted Lincoln’s words as temperate and conciliatory. Northerners heard and read in Lincoln’s speech something quite different than had most southerners. In some instances, however, northerners interpreted Lincoln’s message as mixed and inconsistent, if not downright confusing. Die-hard Republicans praised the speech for its moderation and firmness. From Washington, Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, a Georgian by birth but a steadfast Unionist by allegiance, exalted the inaugural, describing it for his brother as “a noble speech … delivered with a serious and solemn emphasis…. No time was wasted in generalities or platitudes … and no one could doubt that he meant what he said…. Each sentence fell like a sledge hammer driving in the nails which maintain the states.”27 Meigs had keenly recognized that at the heart of Lincoln’s oration lay a fervent desire, a political prayer, for the preservation and perpetuation of the Union.

Though the sincerity of Lincoln’s efforts cannot be denied, it is evident that his desire for the seceded states to abandon their folly because of his moderate words amounted to nothing more than a pipe dream. In his inaugural address, Lincoln’s pragmatism—a political card he often played to great effect—did not result in any pragmatic outcome. Instead, it made him look indecisive, inexperienced, and equivocating. In the South, his appeals for the sanctity of the Union fell on deaf ears.

The South no longer believed or trusted in the Union. Nor did it put any faith in Lincoln, the Black Republican (so called because of the party’s abolitionist sympathies), or the promises he made from the steps of the Capitol. Lincoln must have known that (to paraphrase Shakespeare) the storms of state were upon him. Prayers flew up to heaven for the crisis to be resolved. In Tennessee, the Rev. James H. Otey, a Unionist, cried out for heavenly intervention. “It is God alone,” he wrote, “that can still the madness of the people. Our national sins and ingratitude, I fear, have so provoked His wrath, that now there is no remedy.”28 No remedy, except for the guns of war.

Glenn W. LaFantasie is the Richard Frockt Family Professor of Civil War History Emeritus at Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green.

Notes

1. “Washington Correspondence,” March 1, 1861, in Michael Burlingame, ed., Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860–1864 (Carbondale, IL, 1998), 48–49; Charles Dickens, American Notes, 2 vols. (London, 1842), 1: 281–283, 279.

2. “The New Government,” New York Herald, March 5, 1861; Stephen Fiske, “When Lincoln Was First Inaugurated,” Ladies’ Home Journal, 14 (March 1897): 8.

3. Francis F. Browne, The Every-Day Life of Abraham Lincoln (New York and St. Louis, 1886), 402.

4. “From Washington,” Chicago Tribune, March 4, 1861; William H. Herndon, “Analysis of the Character of Abraham Lincoln,” December 12, 1865, in Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, 1 (September 1941): 356–359.

5. Autobiography of John Shepherd Keyes, ca. 1866, typescript, 185, Keyes Papers, Concord (MA) Free Public Library; Ward Hill Lamon, “Lincoln’s Administration,” ca. February 1886, typescript, 108, Lamon Papers, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; Kathleen McLaughlin, “Reminiscences of Lincoln and His Two Boys,” Chicago Tribune, February 12, 1928; Mrs. Eugene McLean, “When the States Seceded,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 128 (January 1914): 286.

6. Vindex to Lincoln, November 24, 1860, in Carl Sandburg, Lincoln Collector: The Story of Oliver O. Barrett’s Great Private Collection (New York, 1949), 67; J—a J—s to Lincoln, January 14, 1861, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress (hereafter cited as ALP-LC).

7. Charles P. Stone, “Washington on the Eve of War,” Century, 26 (July 1883): 464; Charles Francis Adams Jr., “Lincoln’s First Inauguration,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 3rd ser., 2 (February 1909), 149.

8. John Hay, “The Heroic Age in Washington,” in Michael Burlington, ed., At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings (Carbondale, IL, 2006), 118–119; Charles P. Bowditch to Lucy Orne Nichols Bowditch, March 4, 1861, in Katherine W. Richardson, “We had a very fine day: Charles Bowditch Attends Lincoln’s Inauguration,” Essex Institute Historical Collections, 124 (January 1988): 36.

9. “This Man [T.C. Evans] Heard Lincoln’s Speech,” Belleville New Democrat, March 6, 1911; Ward Hill Lamon, The Life of Abraham Lincoln (Boston, 1872), 529.

10. In the appeals case that went to the Supreme Court, the name of the defendant, John F.A. Sanford, was misspelled.

11. “The Inauguration,” New York Evening Post, March 5, 1861; Lamon, “Lincoln’s Administration,” 109; “The Presidential Inauguration,” Springfield Republican (MA), March 6, 1861; “How Douglas Held Lincoln’s Hat,” Baltimore Sun, March 15, 1861.

12. “The Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln,” Boston Advertiser, March 5, 1861; Wilder Dwight to William Dwight, March 4, 1861, in Wilder Dwight, The Life and Letters of Wilder Dwight… (Boston, 1891), 33; Robert Brewster Stanton, “Abraham Lincoln: Personal Memories of the Man,” Scribner’s Monthly, 68 (July 1920): 34; Clara Barton to Annie Childs, March 5, 1861, in William E. Barton, The Life of Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross, 2 vols. (Boston, 1922), 1: 105; “The New Government,” New York Herald, March 5. 1861.

13. [Charles Francis Adams Jr.], “Washington Letter,” Boston Evening Transcript, March 7, 1861.

14. Lamon, Life of Lincoln, 467; William H. Herndon to Truman Bartlett, July 19, 1887, Bartlett Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

15. All quotations of the First Inaugural are taken from Lincoln, First Inaugural Address—Final Text, March 4, 1861, in Roy P. Basler et al, eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 8 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ, 1953), 4:262-271.

16. The shift in tone resulted from the fact that Seward wrote this paragraph in a long memorandum recommending various changes to Lincoln’s second draft of the address. See First Inaugural Address, Second Printed Draft, with Seward’s Suggested Changes in Red Ink, n.d., ALP-LC.

17. The idea of this peroration came from Seward, but Lincoln revised the New Yorker’s clunky prose into sublime poetry. See William H. Seward, Suggestions for First Inaugural Address, February 1861, ALP-LC.

18. William A. Croffut, An American Procession, 1855–1914 (Boston, 1931), 42–43; Henry E. Shepherd, quoted in “Lincoln at His First Inaugural,” Baltimore American, February 11, 1909.

19. Lamon, Life of Abraham Lincoln, 536.

20. Ibid., 536; Lawrence A. Gobright, Recollection of Men and Things at Washington (Philadelphia, 1869), 289–290; Solomon Foot to [Isaac Toucey?], March 2, 1861, in George Henry Preble, Origin and History of the American Flag, new ed., 2 vols. (Philadelphia, 1917), 2:743–744.

21. Quoted in Charles Francis Adams Jr., Charles Francis Adams, 1835–1915: An Autobiography (Boston and New York, 1916), 97–98.

22. Mary L. Newton to Sarah L. Robinson, March 5, 1861, Robinson Correspondence, Kansas Historical Society.

23. George Ticknor Curtis, Life of James Buchanan, 2 vols. (New York, 1883), 2:509; “The Inauguration,” Washington Intelligencer, March 5, 1861; “Lincoln’s Inauguration,” Baltimore Sun, March 5, 1861; Julia Maria Buel to Sisters, March 4, 1861, in M. Garnett McCoy, ed., Inauguration Day, March 4, 1861 (Detroit, 1960), 6.

24. “The Inaugural Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 5, 1861; “Inaugural Ball in Washington,” New York Herald, March 6, 1861; Lincoln to James Buchanan, March 4, 1861, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln: Supplement, 1832–1865 (Westport, CT, 1974), 62.

25. Nicolay, Memorandum, July 3, 1861, in Michael Burlingame, ed., With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860–1865 (Carbondale, IL, 2000), 47.

26. “President Lincoln’s Inauguration,” Weekly Anglo-African, March 16, 1861.

27. Sue Sparks Keitt to Mrs. Brown, March 4, 1861, Laurence Massillon Keitt Papers, Duke University; Montgomery C. Meigs to John Meigs, March 4, 1861, Montgomery C. Meigs Papers, Library of Congress.

28. “The Inauguration,” Chicago Tribune, March 8, 1861; James H. Otey to Leonidas Polk, December 8, 1860, in William Mercer Green, Memoir to Rt. Rev. James Hervey Otey, D.D., LL.D. (New York, 1885), 91.

Related topics: Abraham Lincoln