Library of Congress

Library of CongressIn this Harper’s Weekly illustration, Union soldiers advance toward entrenched Confederate positions on heights surrounding Fredericksburg, Virginia, on December 13, 1862. Unanticipated and delayed field orders issued by Ambrose Burnside—new to the command of the Army of the Potomac— contributed to the decisive Union defeat.

The Battle of Fredericksburg, fought from December 11–15, 1862, at the crossings of the Rappahannock River in and near Fredericksburg, Virginia, is an example of a collision of misjudgment, bad luck, and poor command.

Major General Ambrose E. Burnside suffered the most criticism for the Army of the Potomac’s failures—the needless slaughter, the futility of its assaults against positions fortified with artillery—but a Congressional investigative body (the Joint Committee for the Conduct of the War) instead found the actions of Major General William Buel Franklin primary in the Union defeat. Franklin’s assault on the Confederate right, often overshadowed by the ill-fated frontal assaults led by other Union commanders, was critical, but the defeat was due not so much to his decisions as to the field orders given him by Burnside.

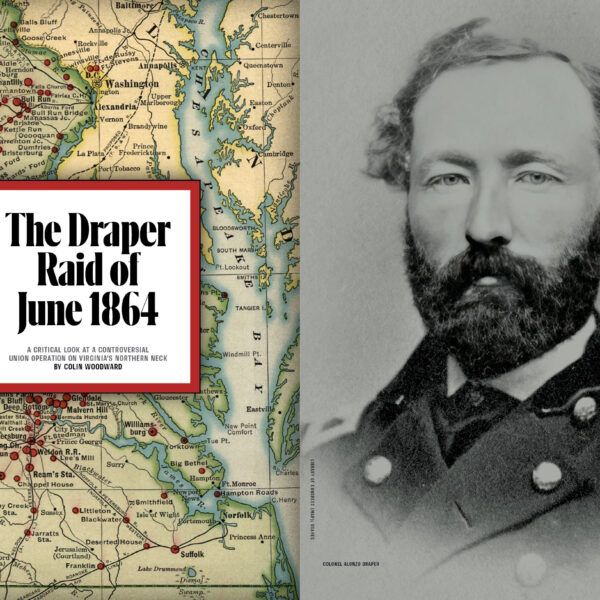

Burnside had assumed command of the army only the month before; his plan for his first major battle was to cross the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg and advance on Richmond, striking swiftly against General Robert E. Lee’s entrenched army. Logistics, delayed troop movements, and a particularly strong Rebel defensive position along the heights surrounding the town presented significant challenges. Burnside decided to reorganize his army’s seven corps into several “Grand Divisions” of two corps each, with one corps in reserve, along with cavalry. These Grand Divisions, commanded by Franklin and fellow Major Generals Joseph Hooker and Edwin V. Sumner, would be responsible for crossing the river and the subsequent attack.1 Franklin, who graduated first in his class at West Point, had distinguished himself in the engineering branch of the U.S. Army and was breveted after the Mexican War. By 1861 he was a general and had commanded corps in the Peninsula and Maryland campaigns of 1862.2

Burnside planned to use Franklin, with Sumner and Hooker, to cross the river using five pontoon bridges; they were done by December 12. Lee also had divided his army into two infantry corps under Lieutenant Generals Thomas J. Jackson and James Longstreet, with cavalry commanded by Major General J.E.B. Stuart. Longstreet’s sector of the Confederate line proved formidable, with strong flanks, a sunken road, and a stone wall. Jackson’s line on the southern flank of Lee’s position was less favorable, in particular at a point called Hamilton’s Crossing.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressWilliam B. Franklin

Burnside joined Franklin on the afternoon of December 12 to confer. Franklin, who saw the potential vulnerability of Jackson’s position, urged Burnside to focus the Union attack on Hamilton’s Crossing, and suggested using most of the troops in his division in a main effort. Franklin’s idea, supported by his corps commanders William F. Smith and John Reynolds, involved forming two large assault columns at night, then launching a forceful attack at daylight on December 13. Franklin realized he would need support from the Grand Division commanded by Hooker and so offered Burnside his plan. Burnside, according to Franklin, Smith, and Reynolds, seemed agreeable and appeared to support Franklin’s scheme. According to the three, Burnside said he would take care of the orders for Hooker, and that Franklin could expect written field orders within a few hours to confirm the details and formalize the plan.3

The field orders used by Civil War armies are part of the long lineage of command-and-control methods employed by modern militaries, including the traditional five-paragraph field orders format currently enshrined in U.S. Army doctrine.4 Field orders are directives intended to address tactical, operational, or strategic issues related to particular military actions and to communicate the commander’s battlefield intentions to his subordinates. They were not the same as general orders. In this era, armies usually began operations with the issuance of general orders or letters of instruction from commanders to subordinates. General orders mainly dealt with details of movement, logistics, supplies, or administrative matters, and were intended to facilitate the demands of moving large forces across expansive spaces for extended periods of time. Field orders, on the other hand, came into play when the demands of a particular engagement or battle required specificity and tactical or operational control in a more refined or detailed context than that provided by general orders.

Civil War field orders could be either written or verbal, and—other than containing the date, time, and place of origination—followed almost no standard format in either army. Civil War commanders followed the Napoleonic tradition of issuing free-form field orders, a system that granted maximum flexibility, but also one where confusion, uncertainty, complexity, and indecision could interfere with a commander’s actual plans or wishes. Civil War officers were thus often left with leeway to interpret field orders. Given the time lag between the generation, transmission, receipt, and interpretation of written orders, problems could be difficult to remedy.

The written field orders Franklin expected from Burnside on the night of December 12 were not only egregiously delayed, but also contained wholesale changes. Although Franklin looked for formal written orders to arrive from Burnside’s headquarters soon after their afternoon conversation, no such orders had arrived by midnight. An alarmed Franklin sent a staffer to investigate the delay and received verbal assurances, but no orders. Franklin was paralyzed by the lack of imperative instructions and did not feel at liberty to prepare his massive attack columns until he knew the operation would commence as planned, with Hooker’s support, at dawn. Burnside had still not sent any written orders by dawn, and only at 7:30 a.m. did Franklin finally receive written orders, with a time of origination noted on them as 5:55 a.m. (The staffer who delivered them blamed icy roads and delays at headquarters.) Burnside’s instructions to Franklin read, in part:

The general commanding directs that you keep your whole command in position for a rapid movement down the old Richmond road, and you will send out at once a division at least to pass below Smithfield, to seize, if possible, the height near Captain Hamilton’s [Hamilton’s Crossing], on this side of the Massaponax, taking care to keep it well supported and its line of retreat open.5

This presented Franklin with problems: First—and contrary to his, Smith, and Reynolds’ understanding of the plan discussed the day before—Burnside’s orders specified using “a division at least” for the attack instead of Franklin’s massive Grand Division of 35,000 men he had planned to employ.

In essence, Burnside changed what Franklin thought was a major attack on Lee’s flank into a smaller probe, presumably with the idea of holding back the rest of Franklin’s strength for other purposes. Second, Burnside’s written morning orders included the directive to “seize, if possible,” the heights near Hamilton’s Crossing, rather than “carry” them in the more customary 19th-century parlance for a major assault. The “seize, if possible” directive represented another of Burnside’s unanticipated decisions made between the December 12 conference with Franklin and the December 13 creation of the orders.6 Franklin was surely annoyed by these changes and delays, and the staff officer who delivered Burnside’s orders was either unable or unwilling to explain them in detail; moreover, Franklin elected not to seek clarification from Burnside. Instead, he made his own fateful decision, and instructed Brigadier General George G. Meade’s division of Reynolds’ corps to attack as ordered. Meade went in with no effective support, and experienced predictably heavy losses. Overall, Union forces suffered more than 12,000 casualties at Fredericksburg, with approximately 4,000 of them occurring on the southern flank, or Franklin’s sector. The balance of the remaining losses occurred elsewhere in similar disjointed and fruitless assaults that did little save demonstrate soldiers’ bravery and their leaders’ ineptitude.

Other grave errors contributed to the defeat at Fredericksburg. Though other frontal assaults resulted in heavy casualties and ended in failure, Franklin’s efforts on the Confederate right were intended to serve as a pivotal part of the Union strategy, and transpired through a series of mistakes and consequential decisions. These, along with delays, a lack of coordination, difficult terrain, adverse weather, and deadly Confederate defenses consisting of entrenched infantry and artillery, proved to be formidable obstacles to the attack. As they attempted to cross the river and march toward their objective, Meade’s men encountered stiff resistance. Despite these challenges, Union forces were able to break through but not to the depth they had anticipated. And they were not followed with sufficient reinforcements; Confederate counterattacks quickly regained the lost ground. The Union forces were unable to maintain their momentum, and the assault petered out in a series of bloody and inconclusive engagements.

The failure of Franklin’s attack was part of a pattern of faulty decisions and missed opportunities. Burnside’s decision to change the plan and delay it, then order repeated frontal assaults against the entrenched Confederate positions on Marye’s Heights, led to massive casualties with no significant results. While Franklin’s attack on the Confederate right was not as costly or disastrous as the frontal assaults elsewhere, they all ultimately ended in failure. In the aftermath, Franklin’s performance was scrutinized by both his superiors and historians. Some critics argued that Franklin’s attack lacked the decisiveness required to break the Confederate line, while others pointed to the many obstacles he faced, including poor communication with Burnside and the absence of proper reconnaissance. Franklin himself faced direct criticism from his peers, including that he had hesitated to fully commit to the attack or that he had allowed his forces to be too cautious. Even worse, the Republican-dominated House investigative committee saw a politically useful scapegoat in Franklin, a well-known Democrat.7 The Union attack on the Confederate right at Fredericksburg remains a poignant example of the challenges faced by Civil War commanders. Franklin’s role, while controversial, underscores the complex nature of military decision-making during the war, where even well-planned strategies led to bad decisions amid unforeseen complications—always with serious consequences.

Andrew S. Bledsoe is associate professor of history at Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee. He is the author of Citizen-Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 2015); co-editor, with Andrew F. Lang, of Upon the Field of Battle: Essays on the Military History of America’s Civil War (LSU Press, 2019); and author of the recently released Decisions at Franklin: The Nineteen Critical Decisions That Defined the Battle (University of Tennessee Press).

Notes

1. Francis Augustín O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock (Baton Rouge, 2003), 24.

2. Stephen R. Taaffe, Commanding the Army of the Potomac (Lawrence, KS, 2006), 18.

3. O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign, 116-118.

4. Matthew L. Smith, The Five Paragraph Field Order: Can a Better Format be Found to Transmit Combat Information to Small Tactical Units? (Fort Leavenworth, KS, 1989), 4–6.

5. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series 1, Vol. 21, 71–72.

6. O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign, 137.

7. Ibid., 460.