JOHN•NY CAKE | noun | A cake made of Indian meal mixed with milk or water. A New England Johnny-Cake is invariably spread upon the stave of a barrel top, and baked before the fire. Sometimes stewed pumpkin is mixed with it….The origin of the word is doubtful. Some imagine it to have originally been journey cake.1

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

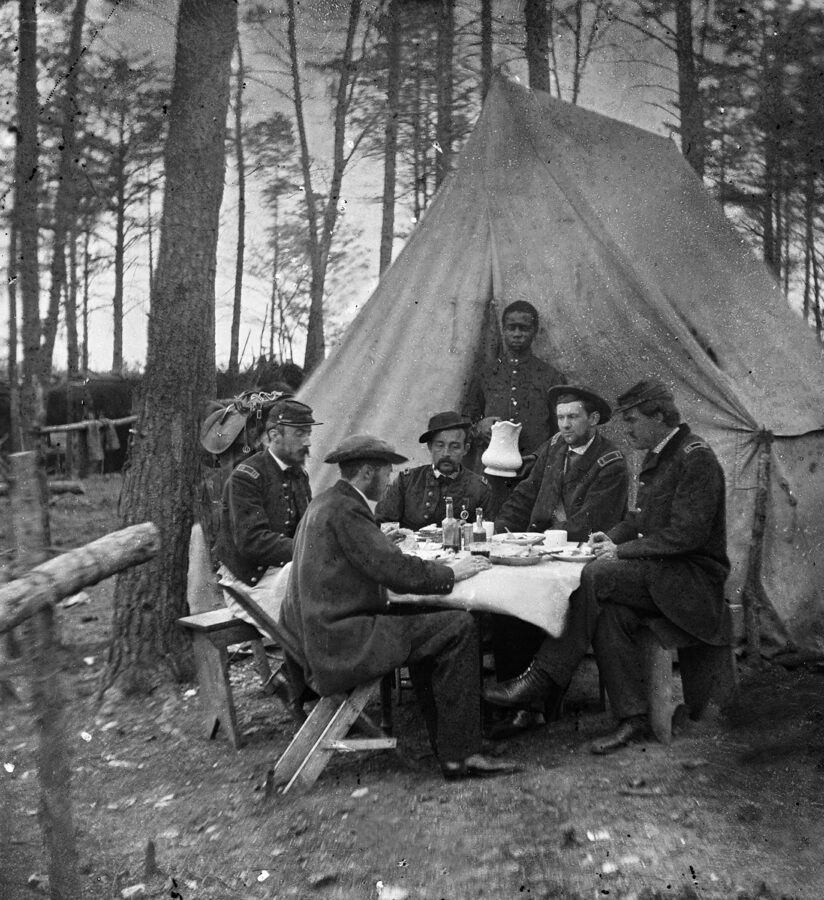

LIBRARY OF CONGRESSIn this April 1864 photograph by Timothy O’Sullivan labeled “Dinner Party Outside Tent,” Union officers are shown having a meal at a makeshift table with a servant-waiter standing nearby. Other than on celebratory days like Thanksgiving, meals were much less formal affairs for the rank and file, who usually dined on such meager fare as “Johnny Cakes.”

ON OCTOBER 3, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln invited the nation “to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens.” Although in the “midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity,” he reminded Americans, “the year that is drawing toward its close has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added which are of so extraordinary a nature that they can not fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God.”2 Although for years many Americans living in the northeast had honored the legendary 1621 gathering between Native Americans and white colonists at Plymouth, Massachusetts, Lincoln was the first president since George Washington, John Adams, and James Madison to officially set aside a day of public thanksgiving. Situated around battlefield campfires, seated at opulent dining tables, or kneeling beside impoverished hearths, Union soldiers and northern civilians might offer prayers of thanksgiving on Thursday, November 26, 1863.

For decades, Sarah Josepha Hale, the outspoken editor of the Philadelphia magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book, had endorsed the holiday and campaigned for its widespread adoption.3 “We have too few holidays,” Hale opined. “Thanksgiving like the Fourth of July should be considered a national festival and observed by all our people … as an exponent of our Republic institutions.”4 Endorsing the holiday in the pages of Godey’s Lady’s Book during the early 1850s, she wrote, “The Fourth of July is the exponent of independence and civil freedom. Thanksgiving Day is the national pledge of Christian faith in God, acknowledging him as the dispenser of blessings. These two festivals should be joyful and universally observed throughout our whole country, and thus incorporated in our habits of thought as inseparable from American life.”5 From 1846 onward, she had written letters yearly imploring the president, several secretaries of state, and the governors of various states to officially sanctify the last Thursday of November as Thanksgiving. As the nation teetered on the brink of war in November 1859, she contended, “If every State should join in union thanksgiving on the 24th of this month, would it not be a renewed pledge of love and loyalty to the Constitution of the United States, which guarantees peace, prosperity, progress and perpetuity of our great Republic.”6 On September 28, 1863, Hale, at 74 years old, wrote Lincoln, urging him to have the “day of our annual Thanksgiving made a National and fixed Union Festival.” “You may have observed that, for some years past, there has been an increasing interest felt in our land to have the Thanksgiving held on the same day, in all the States,” she noted, “it now needs National recognition and authoritative fixation, only, to become permanently, an American custom and institution.”7

What did Hale’s Thanksgiving Day feast entail? “The roasted turkey took precedence on this occasion … sending forth the rich odour of its savoury stuffing … a surloin of beef, flanked on either side by a leg of pork and joint of mutton, seemed placed as a bastion to defend innumerable bowls of gravy and plates of vegetables.” “A goose and pair of ducklings occupied side stations on the table, the middle being graced, as it always is on such occasions, by that rich burgomaster of the provisions called a chicken pie,” she wrote, “plates of pickles, preserves, and butter … filled the interstices on the table, leaving hardly sufficient room for the plates of the company, a wine glass, and two tumblers for each, with a slice of wheat bread.” Sweet desserts included “a huge plumb pudding, custards, and pies of every name and description ever known in Yankee land; yet the pumpkin pie occupied the most distinguished niche.”8

For most Union soldiers, the Thanksgiving spread was scant in comparison. The boys in blue would have been feasting on an assortment of roasted meats, mince pies, sausages, desiccated vegetables, preserved fruits, and various cakes. Rather than their standard military rations, these special holiday meals were often financed and organized by local women’s groups or other charitable organizations. For Thanksgiving, a surgeon in the Union army received “a surprise party here to Day for the Benefit of Soldiers and Nurses,” consisting of “a Choice Thanksgiving Dinner Roast Turkey; Chicken & pigeon & Oysters Stewed.” “I had a good dinner of Baked Chicken & Pudding[,] Boiled potatoes, Turnip, Apple butter, cheese butter, Tea & Trimmings … we live well enough, but cannot Eat Much without being sick,” he wrote.9 In camp near Newbern, North Carolina, Joseph Barlow, a private in the 8th Massachusetts Infantry, enjoyed a “Good dinner of Roast Lamb and Sweet Potatoes and Bread and Butter and Coffee” and with his fellow soldiers had “the day all to ourself.”10 In 1864, another Massachusetts soldier cooked a stuffed chicken above the campfire with his comrades, and they later enjoyed it alongside additional chicken and turkey, which had been “sent to the whole army.”11

Not all soldiers received Thanksgiving meals. For many on a campaign or detailed on work duty, the day passed without any celebration at all. After spending the day unloading supplies near Aquia Creek, Virginia, Meshach P. Larry of the 17th Maine Infantry “did not know what day it was for I take no note of times since I have be[e]n in this show.” After halting for the night, he “heard some grumble about the poor fare for thanksgiving,” and the men received some whiskey to wash down their “hard bread.”12

Library of Congress

Library of CongressSarah Josepha Hale

For many Union and Confederate soldiers, their meager rations usually consisted of coffee and some form of grain: hardtack, cracker, fritter, hoecake, light bread, or Johnny cake. In contrast to the unappealing and dense hardtack biscuits long served by the army and navy, some of these fried breads and baked cakes would have been familiar to many men from their civilian lives. Johnny cake, in particular, had a long history in North America, and especially in the northeast. In 1739, the South-Carolina Gazette advertised “New Iron Plates to cook Johnny Cakes or gridel [sic] bread on.”13 And recipes for and references to the unleavened cornmeal cakes dotted antebellum magazines. The first edition of John Russell Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms, published in 1848, defined Johnny cake as “a cake made of Indian meal mixed with milk or water. A New England Johnny-Cake is invariably spread upon the stave of a barrel top, and baked before the fire. Sometimes stewed pumpkin is mixed with it.”14 Some early linguists trace the bread’s origins to the term “journey cake,” while more recent scholars connected it to the enslaved communities’ culinary influences.15 Despite the cake’s murky origins, many Civil War soldiers enjoyed baked or fried Johnny cakes. After getting off picket duty in March 1863, Norman Markham, the head cook for his company, “had a first rate time [having] got all the milk I wanted & some johny cake & goose eggs for diner.”16

Hale, often considered the “Mother of Thanksgiving,” was a widow with five children when she became editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1837. She retired in 1877 and died two years later at the age of 92. The magazine remained in print until 1896 and, during the late 1870s and early 1880s, published several recipes for Johnny cakes. Drawing sharp distinctions between the various “cakes made with Indian corn-meal,” Johnny cakes were made from “a batter of the consistence employed for pancakes, of the following materials: A quart of milk, a teacupful of wheat flour, a sufficient quantity of Indian meal, three eggs, a teaspoonful of carbonate of soda. Pour batter into a tin pan well buttered inside, bake it in a hot oven, and eat it warm with milk or butter.” This was categorically distinct from Indian pound cake, Indian cake, ginger cake, hoe cake, corn-meal cake, batter cakes, and corn muffins.17 Another recipe for “Yankee Johnny Cake” listed the following ingredients: 1 cup milk; 1 cup wheat flour; 1½ cups of cornmeal; 1 tablespoon of sugar; 1 egg; “Butter size of an egg”; 1 teaspoon baking soda; and salt. The directions specify: “Mix the flour and corn meal with milk, add the egg, sugar and butter, dissolve the soda in a little more milk, stir cream-tartar in the flour dry, [add] a pinch of salt; bake in tin pans about four inches deep. Serve hot for breakfast, to be eaten with butter.”18

With these recipes in hand, the ambitious cooks (and culinary historians) among us can add Johnny cakes to this year’s Thanksgiving Day spread.

Tracy L. Barnett is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia. Her dissertation analyzes the historical origins of America’s gun culture and its relationship to white supremacist ideology. She teaches history at Loyola University Maryland.

Notes

1. Emphasis in original. John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States, Fourth Edition (Boston, 1877), 324.

2. Harper’s Weekly, October 17, 1863.

3. For more on Sarah Josepha Hale, see Patricia Okker, Our Sister Editors: Sarah J. Hale and the Tradition of Nineteenth-century American Women Editors (Athens, 1995).

4. Ruth E. Finley, The Lady of Godey’s, Sarah Josepha Hale (Philadelphia, 1931), 196.

5. “Editor’s Table,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine, Vol. XLV (October 1852): 388.

6. “Editor’s Table: Our Thanksgiving Union,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine, Vol. LIX (November 1859): 466.

7. Sarah J. Hale to Abraham Lincoln, September 28, 1863, Series 1. General Correspondence, 1833-1916, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress.

8. Sarah J. Hale, Northwood: Or, a Tale of New England, Vol. I (Boston, 1828), 109–110.

9. Asa Bean Letter, November 27, 1862, Bean family letters, 1862–1863, Iowa Digital Library.

10. Joseph Barlow to Ellen Barlow, December 2, 1862, Joseph Barlow Collection, U.S. Army Military History Institute (USAMHI), Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

11. Jairus Hammond to Abby Putnam, December 24, 1864, Jairus Hammond Collection, USAMHI.

12. Meshach P. Larry to Phebe Larry, December 9, 1862, Meshach P. Larry Collection, USAMHI.

13. South-Carolina Gazette, December 22, 1739, as cited in “Johnnycake,” Oxford English Dictionary (2019).

14. Emphasis in original. John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States, First Edition (New York, 1848), 402.

15. Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms, Fourth, 324; “Johnnycake,” Oxford English Dictionary (2019).

16. Norman Markham to Eunice Markham, March 20, 1863, N.G. Markham Papers, 1854–1905, the Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Kentucky.

17. Note of caution: The author has not tried out any of these recipes. “Cakes Made With Indian Corn-Meal,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine, Vol. LXXXIV, No. 499 (January 1874): 91–92.

18. “Yankee Johnny Cake,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine, Vol. CIV, No. 620 (February 1882): 185.