USAHEC

USAHECCharles Redington Mudge

As Russia’s war in Ukraine grinds into its fifth month, the Civil War historian in me cannot help drawing parallels between these two conflicts. Ukrainian officials claim to have killed at least 12 Russian generals, with the aid of U.S. intelligence, a feat both astonishing and alarming in modern military operations. While many of these Russian losses may be the result of targeting by classified military intelligence efforts, certainly some of the generals killed in Ukraine died as a result of intensive combat operations.1 In Ukraine, as it was in the American Civil War, combat leadership is a hazardous undertaking; the rate of casualties can be high, particularly among the command echelons of front-line units. Analysts attribute Russian losses to a variety of factors, including doctrinal behavior, organizational considerations, poor morale, and possible erosion of command and control.2 Civil War officers experienced their war differently, of course, but had to negotiate some of the same difficulties in leading men into combat, and also paid a steep price in blood.

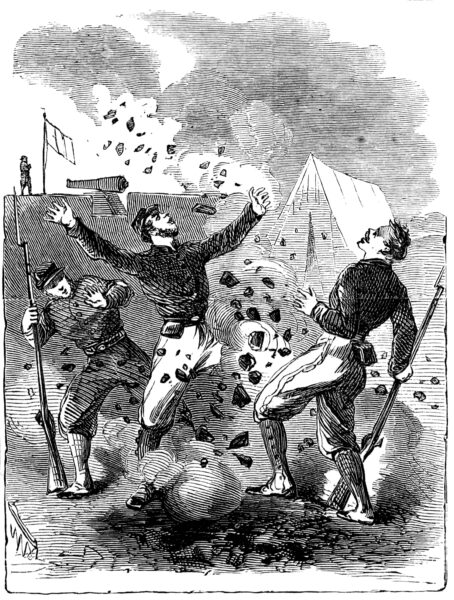

Civil War army leaders’ choices to put themselves in harm’s way were understandably difficult decisions, particularly when the likelihood of injury or death was high, or when such a sacrifice seemed foolish or pointless. Few stories of Civil War combat embody the challenge of mastering the powerful human instinct for self-preservation more than that of young Charles Redington Mudge of the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry. Mudge, a Harvard graduate commissioned as a first lieutenant in May 1861, had risen meteorically through the ranks. He had experienced combat with his unit since the early days of the conflict and been wounded in 1862. A lieutenant colonel at age 23, Mudge had won over his men with his calm leadership and daring style—despite which he had no desire to uselessly give his life. On July 3, 1863, at Gettysburg, he faced an impossible challenge.

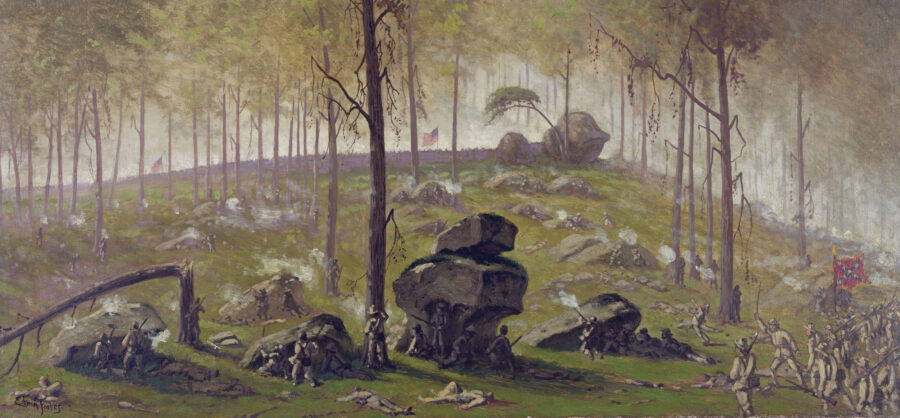

Orders arrived by orderly from brigade headquarters early that morning, and they were dire. The 2nd Massachusetts had formerly occupied a strong defensive position on Culp’s Hill, which it had abandoned for a time, only to have Confederates take up the position. The orders were to drive the enemy from the base of the hill. Mudge knew his men would have to cross an open field and attack a virtually impregnable position with no real hope of success. As regimental commander, Mudge would have to lead his men in this suicidal effort, from the front, exposed and vulnerable. He is said to have reacted calmly to the orders, but wanted to be certain there had not been a mistake. He asked the brigade courier to repeat the instructions. Then, Mudge said, “Well, it is murder, but it’s the order.” When the regiment was formed, Mudge signaled for the assault to begin. “Up, men, over the works! Forward, double quick!” he commanded, and the 2nd Massachusetts followed. Their attack was repulsed, with the regiment suffering more than 100 casualties and half its officers. Mudge was killed instantly by a bullet to the throat.3

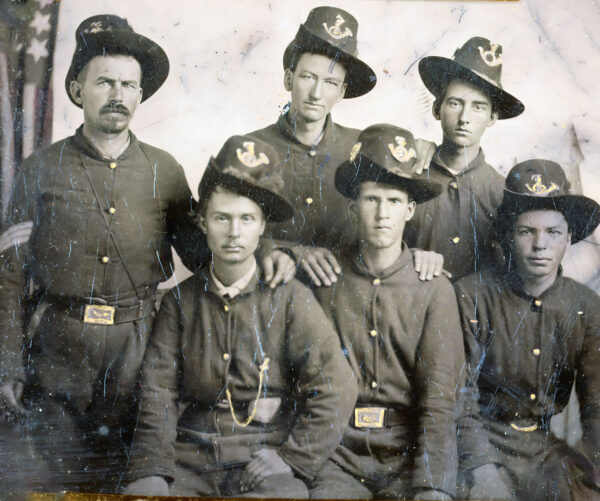

The awful attrition of combat officers in the Civil War is not unique to that conflict; nevertheless, the cost of battlefield leadership in the war is one of its best known, if least understood, realities. To illustrate, Union junior officers—those at the ranks of second and first lieutenant or captain—suffered a 43 percent casualty rate during four years of war, while Confederate junior officers sustained a 47 percent casualty rate. This is extreme. Casualty rates for all Union soldiers are estimated at 16 percent and for all Confederate soldiers at 31 percent.4 Generals and officers of higher rank were less likely to be killed or wounded in combat, but the risk remained. At the 1864 Battle of Franklin, for instance, six Confederate generals died, and multiple major battles throughout the war cost both sides high commanders as well as field and junior officers in significant numbers.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressIn this painting by Edwin Forbes of the Battle of Gettysburg, Union and Confederate forces fight for possession of Culp’s Hill, where Charles Redington Mudge and the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry played a significant part.

Why? There are a number of factors that contributed to Civil War officers suffering extraordinary casualties. There was intense cultural pressure within armies of volunteers for officers to lead by example, including to display indifference to danger and willingness to take charge from the front. Officers also made good targets, wearing conspicuous shoulder boards, braid, and carrying swords that distinguished them from the enlisted men in their ranks. Moving and fighting with massed units in 19th-century armies required officers to shout commands and take positions that let them be seen and heard, but also made them targets for enemy marksmen. This all led to high loss rates in Civil War armies that, in contrast to the Russian example in Ukraine, had little or nothing to do with questions of competence or capability; rather, it reflected the harsh realities of the conflict.

Sometimes, to their own surprise, officers rose to the challenge. “I stood up and walked around among the men, stepping over them and talking to them in a joking way, to take away their thoughts from the bullets, and keep them more self possessed,” wrote William Francis Bartlett, a captain in Mudge’s 2nd Massachusetts. “I was surprised at first at my own coolness. I never felt better, although I expected of course that I should feel the lead every second, and I was wondering where it would take me.”5 Civil War leaders had little choice but to take risks if they wished to be effective, and because they served as the heart and soul of volunteer units, had to bear the weight of expectation that they fulfill their roles or perish. Mudge was among the many who did both.

Andrew S. Bledsoe is associate professor of history at Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee. He is the author of Citizen-Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (LSU Press, 2015); the co-editor, with Andrew F. Lang, of Upon the Field of Battle: Essays on the Military History of America’s Civil War (LSU Press, 2019); and author of the forthcoming Decisions at Franklin: The Nineteen Critical Decisions That Defined the Battle (University of Tennessee Press).

Notes

1. “U.S. Intelligence Is Helping Ukraine Kill Russian Generals, Officials Say,” nytimes.com/2022/05/04/us/politics/russia-generals-killed-ukraine.html (Accessed May 4, 2022).

2. “Why Russia has Suffered the Loss of an ‘Extraordinary’ Number of Generals,” abcnews.go.com/International/russia-suffered-loss-extraordinary-number-generals/story?id=84545931 (Accessed May 8, 2022).

3. Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg—Culp’s Hill & Cemetery Hill (Chapel Hill, 1993), 350.

4. Andrew S. Bledsoe, Citizen-Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (Baton Rouge, 2015), 161–162; Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York, 2008), 274 note 2.

5. William Francis Bartlett to My Dear Mother, October 25, 1861, in Memoir of William Francis Bartlett (Boston, 1879), 23–24.