Library of Congress

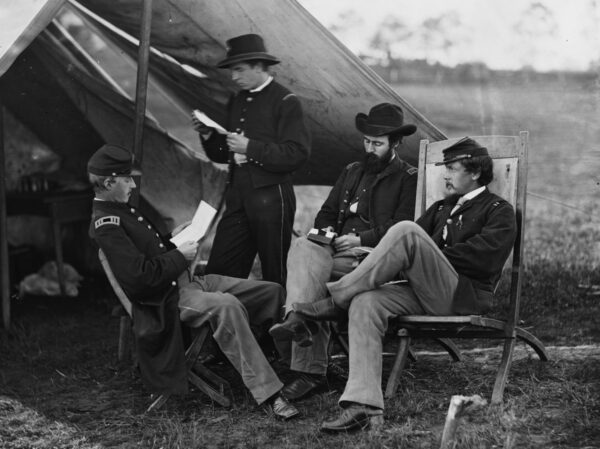

Library of CongressUnion soldiers crowd the grounds of Andersonville Prison, where many of the men who participated in Lieutenant Edward Brooks’ ill-fated raid during the Petersburg Campaign spent time in captivity.

As Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant considered his options following the bloodbath at Cold Harbor on June 12, 1864, he received an unexpected letter from a young officer suggesting a bold raid to burn railroad bridges behind Confederate lines. Apologizing for the “exceedingly unmilitary act” of addressing the commanding general directly, Lieutenant Edward P. Brooks of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry and the legendary Iron Brigade proposed selecting 30 men for a three-day mission to destroy the junction of the Richmond and Danville and the Virginia and Tennessee railroads at Burkeville. The result of the raid would “be equal to any demonstration of this sort ever made by our Army here.” There is no evidence the plan was given much thought before Grant approved it a week later. He ordered Major General George G. Meade to coordinate Brooks’ proposal with Brigadier Generals James Wilson and August Kautz’s planned cavalry raid against the railroads that carried supplies from Petersburg to Robert E. Lee’s army; the small band would accompany the larger expedition until it was “time for cutting loose.”1

Brooks quickly chose his men from the Iron Brigade, which by summer 1864 consisted of the 6th and 7th Wisconsin, 24th Michigan, and the 19th and 7th Indiana infantry regiments. They were experienced soldiers, mostly “veteran volunteers,” men who had enlisted in the summer of 1861 and, in return for a bounty and a 30-day furlough back home, had reenlisted in early 1864. A number of them had been wounded, and some had just returned to their regiments in the spring.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressIn this sketch from Harper’s Weekly, Union soldiers exchange fire with distant Confederates during the Battle of Cold Harbor. Shortly after the bloody fight, Ulysses S. Grant approved Lieutenant Edward P. Brooks’ idea for a raid to burn railroad bridges behind enemy lines.

The hastily assembled band departed less than two weeks after Grant received Brooks’ letter. It is easy to imagine the men feeling both anxious about the unknowns facing them, but also relieved to be free of the almost daily, grinding combat they had survived since the start of the Overland Campaign on May 4. Indeed, the Iron Brigade would suffer the most casualties of any brigade in the Union army during the war, including hundreds of men killed, wounded, and missing in May and June 1864. By the end of the summer the 2nd Wisconsin would cease to exist and the 6th Wisconsin would have but 75 men reporting for duty.

Whatever purpose influenced the men as they departed camp on June 21, in less than 48 hours they would be prisoners of war. A few would die in prison; the health of many others would be permanently damaged. Brooks would never recover from his own prison experience, nor would he ever redeem his reputation among his former comrades. A model of hubris and poor planning, the “Brooks Expedition” shows what happens when an officer’s ambition meets with a general’s willingness to try anything to turn the course of a campaign.

***

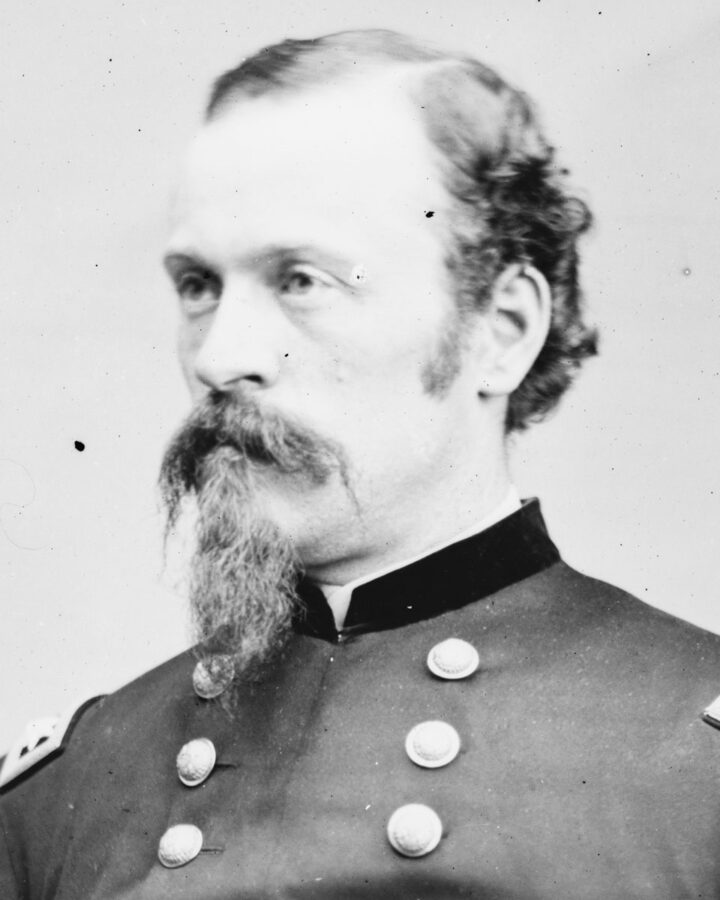

Library of Congress

Library of CongressJames Wilson

A printer and reporter for the Wisconsin State Journal in Madison, Edward Brooks had enlisted in the 6th Wisconsin as a teenager in the summer of 1861. He rose rapidly through the ranks, becoming a sergeant, then lieutenant, then regimental adjutant, with a stint on the brigade staff, all in 18 months. Some suspected that Brooks had benefited from the political influence of his uncle and employer, David Atwood, who was a founder of the Republican Party, editor of the State Journal, general in the Wisconsin militia and, by 1861, a state legislator.2 One of Brooks’ longtime comrades, James Sullivan, claimed the “rosy-cheeked” and “boyish” Brooks applied hair dye to make his wispy mustache visible. Sullivan noted that Brooks took soldiering seriously—perhaps a little pompously—and “although a most gallant son of Mars, he was no less a worshipper at the shrine of Venus,” who as a staff officer with a fair amount of freedom to move about the countryside was always on the lookout for good food and pretty girls. “I know not how many dark-eyed daughters of the south were smitten by his handsome, pleasant face” and “civil, purty spoken tongue,” Sullivan wrote.3 Still, Brooks had taken to the war rather naturally; the 6th Wisconsin and its young officer had been part of some notable moments: In their first action, they (as part of the Iron Brigade) fought to a standstill a far larger force of Confederates under Stonewall Jackson at Gainesville on the eve of Second Manassas; stormed through the Cornfield at Antietam; and helped to buy time on the first day at Gettysburg by charging an unfinished railroad cut and capturing most of a Confederate regiment. Brooks played a vital role in the fight at Gettysburg, taking a couple of dozen men around to one end of the cut and unleashing a deadly crossfire to help force the Rebels’ surrender.4

More dramatically—and perhaps memorably to Brooks—during the first few months of 1863, the regiment had conducted a lightning raid into Virginia’s North Neck, confiscating Confederate property and liberating 70 enslaved people. In May, the 6th had opened the Chancellorsville Campaign with a bold amphibious attack under fire across the Rappahannock River, where they captured or killed scores of Confederates and seized a bridgehead that allowed engineers to complete a pontoon bridge.5

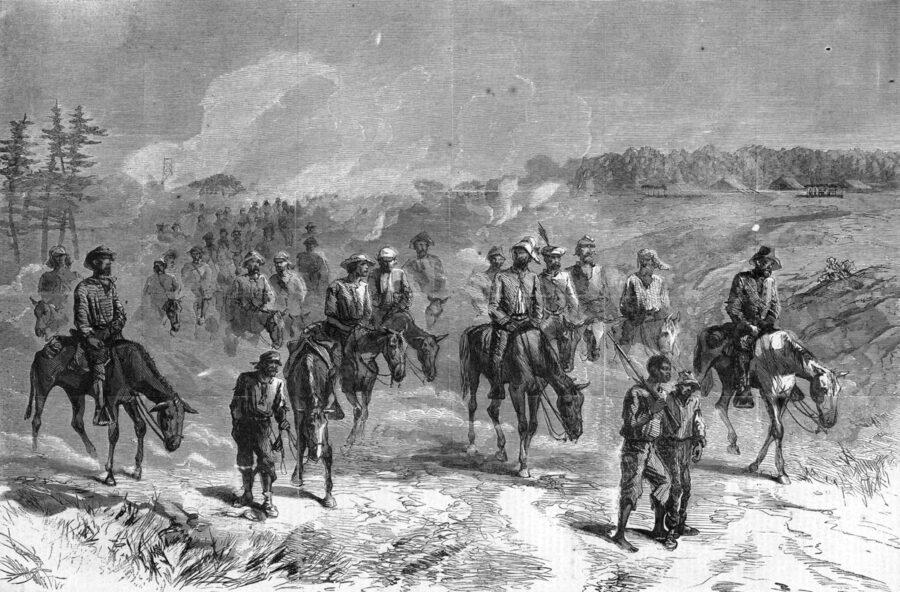

Harper’s Weekly

Harper’s Weekly Brooks’ “secret expedition” jumped off with the larger (and similarly failed) Wilson-Kautz Raid, during which the Union force lost about a third of its men. Above: A group of Wilson and Kautz’s men are depicted staggering back to Union lines after the raid in a sketch from Harper’s Weekly.

Brooks was captured late in 1863 and had only rejoined his regiment in late March 1864 after he and nearly 1,000 other Union POWs were exchanged. Brooks may perhaps have been included in the exchange because of the intervention of President Abraham Lincoln, who was a political acquaintance of Brooks’ employer and benefactor Atwood. Before the war, Lincoln had given a speech at the Wisconsin State Fair at the invitation of Atwood and other local Republicans; in 1862 Lincoln had appointed Atwood to a federal post. In March 1864, Lincoln had urged Major General Benjamin Butler to make sure Brooks was in the cohort of exchanged prisoners. “I desire, that if practicable his special exchange be effected for a rebel prisoner of same rank. Have you one to send, and can you arrange it at once?” Butler made the proposed deal within a week.6

By 1864, Brooks had compiled an excellent combat pedigree—but he had never led an independent command in combat. Where Brooks got the idea for his dramatic plan is unclear. Perhaps he was encouraged by the interest taken in him by the president, or inspired by the drama of the battles and raids he had experienced, to attempt some glory and escape the grinding bloodshed that had ravaged his veteran brigade over the previous two months. In any event, the young lieutenant—apparently going over the heads of a number of commanding officers at the regimental and brigade levels—received permission to select his men, obtain their mounts, and head out with the larger Wilson-Kautz expedition to operate behind Confederate lines.

In the next few days Brooks selected 28 men, eight from the 6th Wisconsin, 10 from the 7th Wisconsin, five from the 24th Michigan, and five from the 7th Indiana. The “secret expedition,” as it was called in some of the regimental records, would jump off with the Wilson-Kautz Raid, as the larger operation came to be called, which consisted of 5,000 cavalrymen conducting a raid on southern railroads. In the end, the raiders destroyed a few score miles of track and temporarily disrupted Confederate communications—while losing over a dozen artillery pieces and perhaps a third of their men, most of whom were captured—and by July 2 had staggered back to Union lines. Brooks was apparently not alone in poor planning, and the men under his command taken prisoner were just a small portion of the total number of casualties from this brief special operation.7

Perhaps obscured by the bigger failure of the Wilson-Kautz Raid, the “Brooks Expedition” did not find its way into official reports. However, the Petersburg Daily Express reported it, and the pro-Confederate newspaper’s mocking article was picked up by The New York Times on July 7, just two weeks after the expedition had set out. The story provided the basic narrative to which survivors and others referred for decades.

Here is what happened: Having captured and released a Confederate captain home on leave on their first night out, Brooks and his men on their second night went into camp without setting guards. The next morning, that same Confederate captain, accompanied by seven farmers armed with shotguns, surprised Brooks’ patrol and demanded their surrender. “Overwhelmed with surprise and panic-stricken, the valiant Brooks”—the Daily Express’ account was rife with sarcasm—“asked for time to consult his men.” The Confederate captain continued his bluff, demanding that the northerners “stack their arms in the road and march immediately up to the Dixie boys, or the Dixie boys would march to them.” They did as they were ordered. “Upon finding that they had surrendered to six citizens, armed only with double-barrel shotguns, their mortification was great, but it was too late to retrieve their misfortune.” Clearly, the Yankees “had been out-generaled, and the only alternative was to submit.” After surrendering, the “ireful Yankees threatened vengeance to Capt. White and his little squad if they were ever liberated. But no one feared their threats. They are, ere this, all safely shipped to Georgia, where they hope they will have time allowed them for further repentance”—a reference to the dreadful prison camp at Andersonville. The Times borrowed the Express’ snide headline—“A Gallant Affair”—and related the embarrassing claim that the commanding officer (“a scamp named Brooks,” who for some reason the Confederate paper thought was a “renegade” from Virginia) had “shed tears.”8

Although the rather jaunty tone of the newspaper article suggests that Brooks’ failed foray was a wartime “caper” gone awry, an account by one of the captured soldiers, Thomas Newton, hinted at another element. Newton recalled over 20 years later that he and the other men were ordered to report to Brooks, who swore them to secrecy and laid out the plan. “We of course had all confidence in him, as a true and brave officer,” Newton remembered. When the Confederates interrupted breakfast with their surrender demand, Brooks told his men that he had been out all night scouting for a route through Rebel lines, had found Confederate units in every direction, and had determined that “fighting would be useless.” Newton recalled that the men “concluded we were sold; bought for a price, but as we could not prove it, all we could do was to suffer the consequences, of which tongue cannot describe or pen portray.” He neglected to say who had “sold” them—a local farmer, one of the other soldiers, Brooks himself—but Newton’s insinuation adds a layer of intrigue to a story of incompetence.9

Later in his life, when applying for an increase to his military pension, Brooks wrote of his expedition that he had been “in command of a detachment of scouts,” who, “while in line of duty, was captured by the enemy … in the enemy’s country, while acting under orders” from Grant. This pale defense failed to convince anyone that the blame might lie in some other place.10

USAHEC

USAHECRufus Dawes

Lieutenant Colonel Rufus Dawes, who commanded the 6th Wisconsin at the time of Brooks’ expedition, referred briefly to the incident in a footnote in his 1898 memoir, where he concluded simply, “If we may credit the Confederate reports they were, owing to the negligence of their commander to put out the proper guards, surprised and captured by a much smaller force.” The regimental history of the 24th Michigan was less judgmental in its description, repeating the details but adding the image of the armed farmers positioning themselves so that only their hats and horses’ heads could be seen, making it seem as though they were the first rank of a larger force.11

Over the years, several articles in the Milwaukee Sunday Telegraph—a weekly that featured at least two pages of Civil War veterans’ news and memoirs in every issue—mentioned the incident with more prejudice, combining commentary on Brooks’ failure with stories of the effects of imprisonment on Brooks and his men. “We all know the unfortunate result” of the expedition, wrote “Grayson” in 1881, “how the command was surrounded and captured.” Another piece repeated the well-known account of how “on the second day out the poorly officered command surrendered, and the raiders were taken to Andersonville.” The article reported the plight of several survivors, but passed over most of Brooks’ postwar life, simply saying with a twist of the knife that he “landed in Washington where he has since conducted the National Republican better than the raid.” The tone and details of the story got worse as time passed. A few years later the Telegraph ran a rehash of the story that asserted that “less than half of the thirty picked men ever returned. Some of them died at Charleston, others were starved to death at Andersonville, and others still were run down and killed by bloodhounds while trying to escape. Two or three of them became insane, but have since recovered their reason.”12

As the newspaper suggested, the capture of Brooks and his men itself was a prologue to the more compelling narrative and greater tragedy. Newton’s lengthy memoir, published in the Sunday Telegraph, was a graphic account of the cruelties endured in the infamous Andersonville prison camp—at the hands of trigger-happy guards and organized gangs of prisoners alike—and a few other prisons. Brooks does not appear again in Newton’s narrative, which ends with a summary of his own postwar life settled on a farm in Waushara County. His “general health is not good,” but he was “able to be about most of the time.” Newton’s prison camp hardships left him with rheumatism and a spine ailment that left one leg shorter than the other, and himself more than five inches shorter than when he was a soldier. Newton was 57 when he died in 1896.13

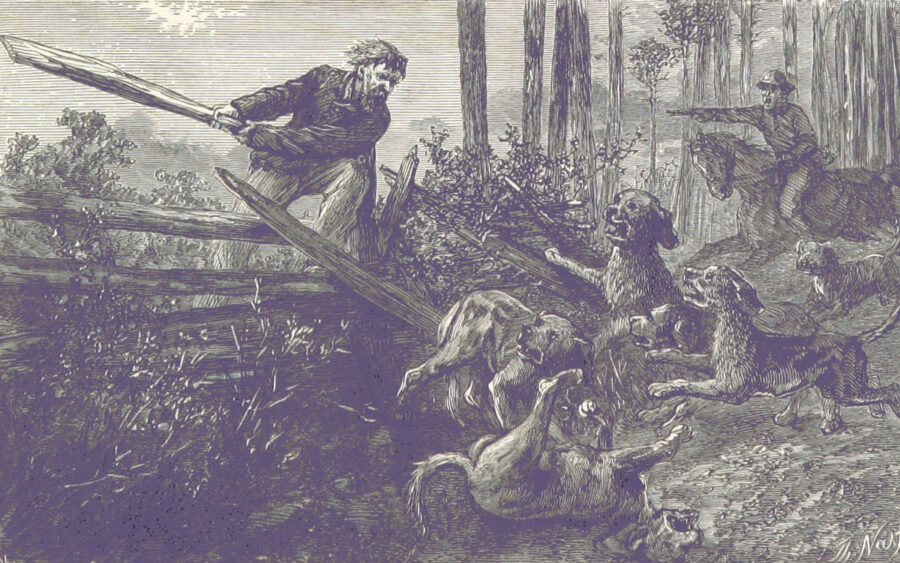

The Soldier’s Story of His Captivity at Andersonville, Bell Isle, and Other Rebel Prisons (1866)

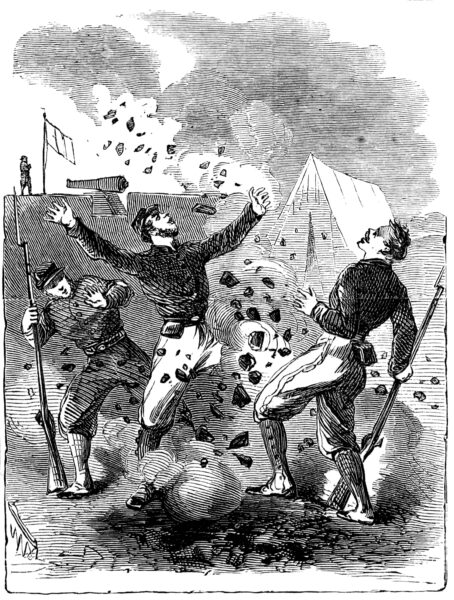

The Soldier’s Story of His Captivity at Andersonville, Bell Isle, and Other Rebel Prisons (1866)The men who were part of Brooks’ raid experienced many hardships—not only during their time as prisoners of war, but also (for those who survived the conflict) myriad health issues over the years of their postwar lives. Above: A postwar illustration depicts an escaped Union POW being chased down by dogs, something Brooks and several of his men experienced in the months after their ill-fated expedition.

More details on what happened to several of the men emerge from individual pension files and the descriptive book of the 6th Wisconsin, a massive ledger compiled in the 1880s from numerous regimental and company reports. It is clear that the experience not only killed at least two members of the regiment, but may also have shortened the lives of several others, as suggested by the early dates on which they received pensions and their relatively short life spans after the war. John Bowman, who had fought in all of the regiment’s battles before being detached for “special service,” died at Andersonville (or, perhaps, in Salisbury Prison in North Carolina). Levi L. Tongue’s entry notes he was pensioned in 1868 and died sometime before 1890, when he would have turned 47. Samuel Waller also survived and became a preacher after the war; he died at 37 in 1880. Silas Lowery of Company B joined the expedition; his entry in the descriptive book indicates he remained in prison until being paroled on March 2, 1865. He spent the last several years of his life in the Minnesota State Soldiers Home. Henry Lowell, another member of the expedition, was paroled in Charleston in December 1864. Samuel Gordon and John St. Clair of Company K were also among the captured; St. Clair was held in Wilmington and Charleston until being released in December and returning to the 6th after the first of the year. He died sometime before 1890, when he would have been 53. Virtually none of the men from Brooks’ regiment who survived the expedition lived into old age.14

Like many of the men he led, Brooks seems never to have recovered his health after his experience as a prisoner of war. From his sickbed in 1884, Brooks told a court clerk, who had come to his home to take his testimony for a pension claim, that the Confederates had taken him first to Andersonville and then Macon. Brooks was among 500 officers transported to Charleston later in the fall. On the way, about 70 jumped from the moving train and tried to escape “through the swamps and bayous.” Hunted by dogs, Brooks and several others were recaptured. They again were sent to Charleston, where they were purposefully exposed to fire from Federal naval vessels. During yet another rail journey, Brooks and a few others managed to saw a hole in a railroad car while being transported and slipped out when the train stopped for water. They headed for East Tennessee, struggling through “the swamp known as Adam’s Cane Brake, swimming and wading, without food.” One of their companions gave up and could not go on; Brooks assumed he died. They were recaptured after a week or so, and taken to Columbia. They escaped yet again—and were recaptured yet again. By this time it was December, when Brooks escaped a fourth time—this time on his own. He canoed and waded through icy waters in and around the Congaree River, lacerating and freezing his feet, finally making it to the coast. He found another canoe and paddled out to a Union blockade ship and safety.15

An officer from a Pennsylvania regiment, Frank Krepps, testified on behalf of Brooks’ pension application that he had “escaped three different times in company of Edward P. Brooks and I am satisfied from the exposure that we both underwent that it is a most remarkable thing that either one of us are alive.” Brooks survived his ordeals, but for the rest of his life never enjoyed more than a few months of good health before his various ailments rendered him bedridden for three or four months at a time.16

Brooks did not return to the 6th or to Wisconsin. In his pension affidavit, Brooks summarized his life after the war: “I lived or resided in Washington, DC, & Hyattsville, Ind., from 1865 until 1880, during which period I travelled & remained temporarily in the Southern states as a correspondent of The New York Times, particularly in North Carolina, Louisiana, South Carolina & Florida.” His political connections apparently continued to help him; “While in Cork, Ireland, from February 1880 until December 1881, I was United States Consul.” Brooks later worked as a journalist in Illinois. He was completely unable to perform manual labor (the litmus test for receiving a federal pension), and “for weeks and months at a time” he was even unable to perform the “mild labor” of being a journalist. Asthma and heart troubles followed him; Brooks, 50, and living with his mother in Washington, D.C., died in 1893.17

Brooks’ obituary appeared in the Milwaukee Telegraph in 1893, a last chance to remind readers of Brooks’ wartime notoriety. It is worth quoting: “Little Ed. Brooks is dead. How well many Wisconsin soldiers remember the young man when he came to Camp Randall, smooth faced, boyish, full of confidence and ready to work. Because of his connections in Wisconsin he was given promotion before he had shown that there was good fighting material in him, but he was a fighter and won other promotions, the highest being adjutant of his regiment.” After the grudging compliments, the obituary got to the point: “His military career was obscured somewhat by a misfortune which befell an expedition into the Southern Confederacy which he headed. He surrendered his force of thirty men the second day out and most of those thirty men died in prison, or have been wrecks ever since.” After a brief summary of his postwar career—“he never returned to Wisconsin”—the piece ended with a stroke of dismissiveness: “Poor little Ed. Brooks. His life was not what he expected it to be, and was in some respects, a disappointment to his friends.”18

Brooks was not yet 23 when he was mustered out of the army in January 1865, and he spent at least some of his painful postwar life advocating for civil rights for the formerly enslaved. He may have always leaned in that direction; his mentor Atwood was a Republican leader in Wisconsin and the State Journal where Brooks worked before he enlisted was a decidedly anti-slavery newspaper. Perhaps he felt an obligation; his fellow POW Krepps testified that “the only treatment I ever knew of [Brooks] receiving was from myself or from our friends the Negroes who were the true friends of the poor prisoners.” In any event, soon after the war was over, Brooks became proprietor and editor of a short-lived newspaper called the Journal of Freedom, established for the freed people of North Carolina in the fall of 1865 while a freedmen’s convention was being held in Raleigh. The New York Times noted that Brooks had “served four years in the war, and owes slavery a grudge which he will repay in this philanthropic work.” Another paper called the Journal “bold and fearless.” It was no small thing for a white man to set up as an advocate of black equality while living in a former Confederate state in the fall of 1865, and Brooks felt “proud of the fact that he is the humble instrument designed by the Supreme Intelligence” to accomplish “the truly republican principle of Universal Suffrage.” In this, his “Salutatory” editorial in the first issue, he celebrated the victory over the “unholy rebellion” and the restoration of “free speech” and loyalty in the former Confederacy. Yet “the victory is only half accomplished,” and he vowed to work for suffrage for “persons of African descent.” Only then would “the establishment of laws based on principles of true equality, the education and elevation of our people, and the building up of the regenerated South on a firm and lasting basis of Republicanism,” be accomplished.19

The Journal of Freedom lasted only a few weeks, but Brooks would go on to other endeavors. The “Brooks Expedition”—a too grand name for such a pitiful failure—was just one small story in a phase of the conflict when commanders desperately sought ways to break the bloody war of attrition emerging in Virginia in the summer of 1864. That stalemate might have seemed to preclude zealous young officers’ chances at glory, encouraging them to take unwise risks. There is no reason to suppose that the older veterans who rode off with Edward Brooks that June morning shared their young commander’s ambition, but it is clear that all of them shared the war’s same tragic wounds.

James Marten is professor emeritus of history at Marquette University, a former president of the Society of Civil War Historians, and author, editor, and co-editor of two dozen books, including The Children’s Civil War (1998) and Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America (2011). He is currently writing a book on the 6th Wisconsin Infantry.

Notes

1. Grant to Meade, June 20, 1864, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 11: June 1–August 15, 1864, 96-97, digital edition, Mississippi State University: msstate.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/USG_volume/id/18637/rec/11 (accessed December 13, 2021).

2. “David Atwood,” Historic Madison, Inc. (accessed August 13, 2023); Diana P. Parsell, Eliza Scidmore: The Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington’s Cherry Trees (New York, 2023), Chapter 1. Edward Brooks was Scidmore’s half brother.

3. William J.K. Beaudot and Lance J. Herdegen, eds., An Irishman in the Iron Brigade: The Civil War Memoirs of James P. Sullivan, Sergt., Company K, 6th Wisconsin Volunteers (New York, 1993), 82–83.

4. For the Iron Brigade in general and the 6th Wisconsin in particular, see Lance J. Herdegen, The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2012) and Lance J. Herdegen and William J.K. Beaudot, In the Bloody Railroad Cut at Gettysburg: The 6th Wisconsin of the Iron Brigade and its Famous Charge, 2nd ed. (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2015).

5. Report of Colonel Lucius Fairchild, February 16, 1863, in United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series 1, Vol. 25, Pt. 1, 16–17 (hereafter cited as OR).

6. “Abraham Lincoln and Wisconsin,” Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom: abrahamlincolnsclassroom.org/abraham-lincoln-state-by-state/abraham-lincoln-and-wisconsin (accessed August 13, 2023); Lincoln to Butler, March 18, 1864, in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 7 (accessed August 14, 2023).

7. A. Wilson Greene, “Petersburg, Virginia, June-August 1864,” in Lorien Foote and Earl J. Hess, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the American Civil War (New York, 2021), 491–492.

8. The New York Times, July 7, 1864.

9. Milwaukee Sunday Telegraph, September 19, 1886.

10. Edward P. Brooks Pension File, Certificate 293883, National Archives.

11. Rufus Dawes, A Full Blown Yankee of the Iron Brigade: Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Lincoln, 1999), 295; O.B. Curtis, History of the Twenty-Fourth Michigan of the Iron Brigade (Detroit, 1891), 267.

12. Sunday Telegraph, January 30, 1881, February 1, 1880, August 17, 1884.

13. Ibid., September 19, 1886

14. Companies H, I, B, C, and K, Sixth Wisconsin Descriptive Book, Wisconsin State Historical Society. The descriptive book was organized by company and by individual soldiers’ last names.

15. Brooks Pension File.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Milwaukee Telegraph, May 13, 1893.

19. Journal of Freedom, October 14 and September 30, 1865; Patrick Young, “The Journal of Freedom: A Newspaper for the Black Community of Raleigh, N. C.,” The Reconstruction Era Blog, August 24, 2021:(accessed August 31, 2023).