Richland County Public Library, Columbia, SC

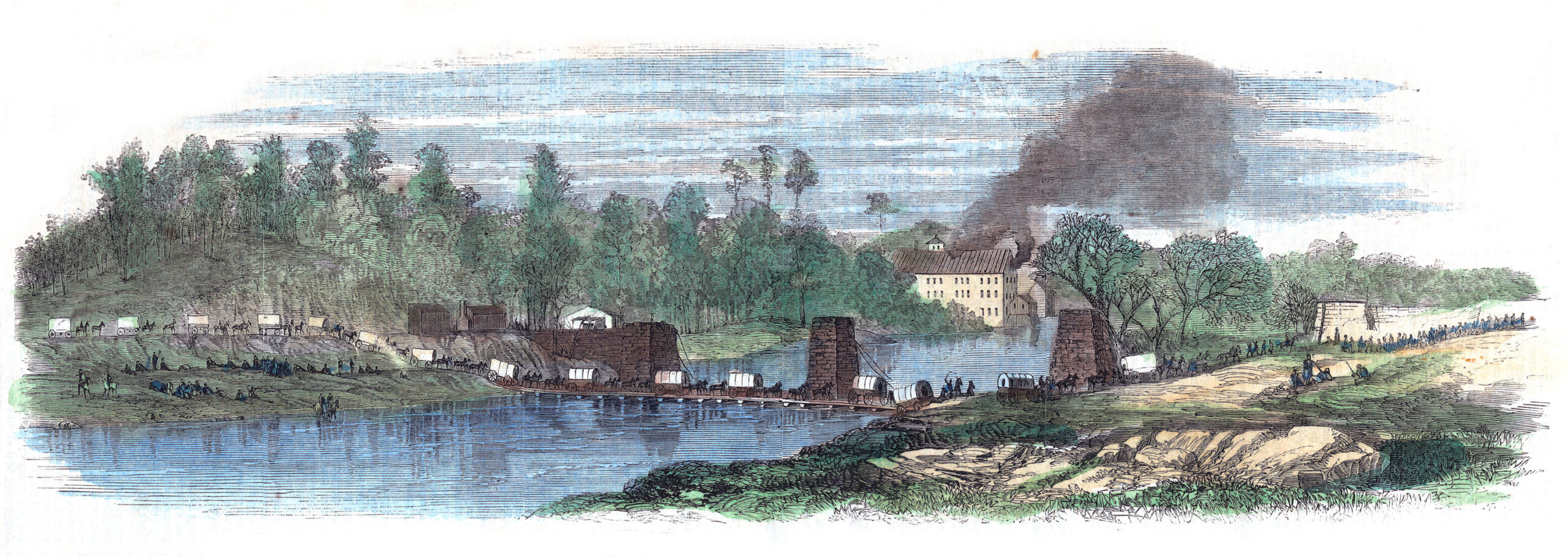

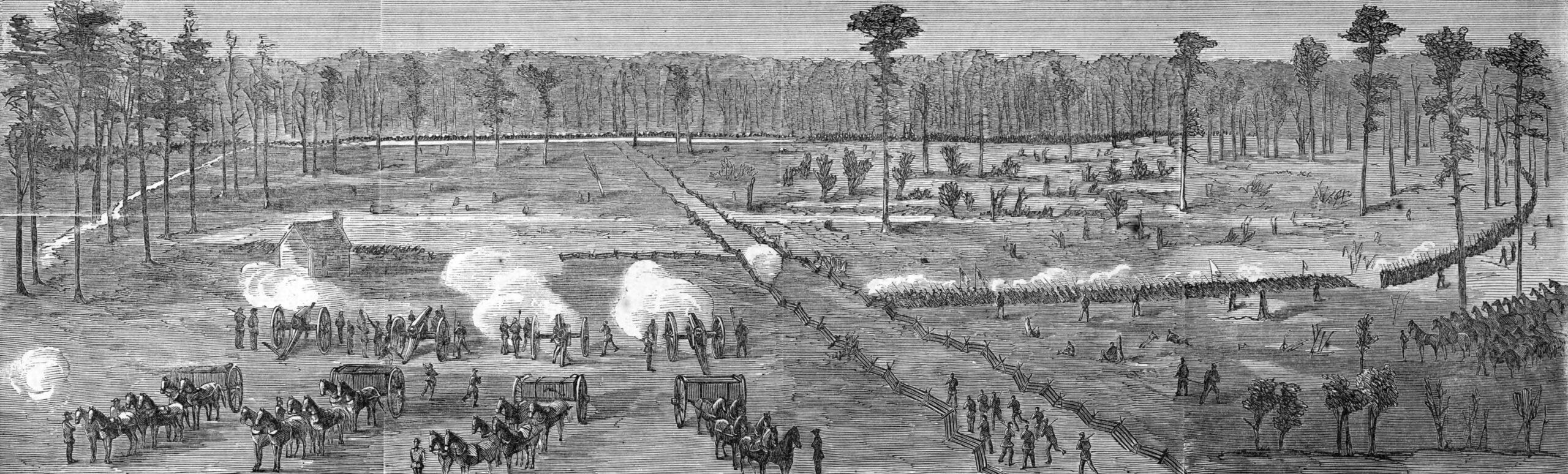

Richland County Public Library, Columbia, SCIn this illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, William T. Sherman’s army is depicted crossing the Saluda River on its way north through South Carolina. A month later, in March 1865, Sherman’s soldiers would clash with Confederates at the Battle of Averasboro in North Carolina.

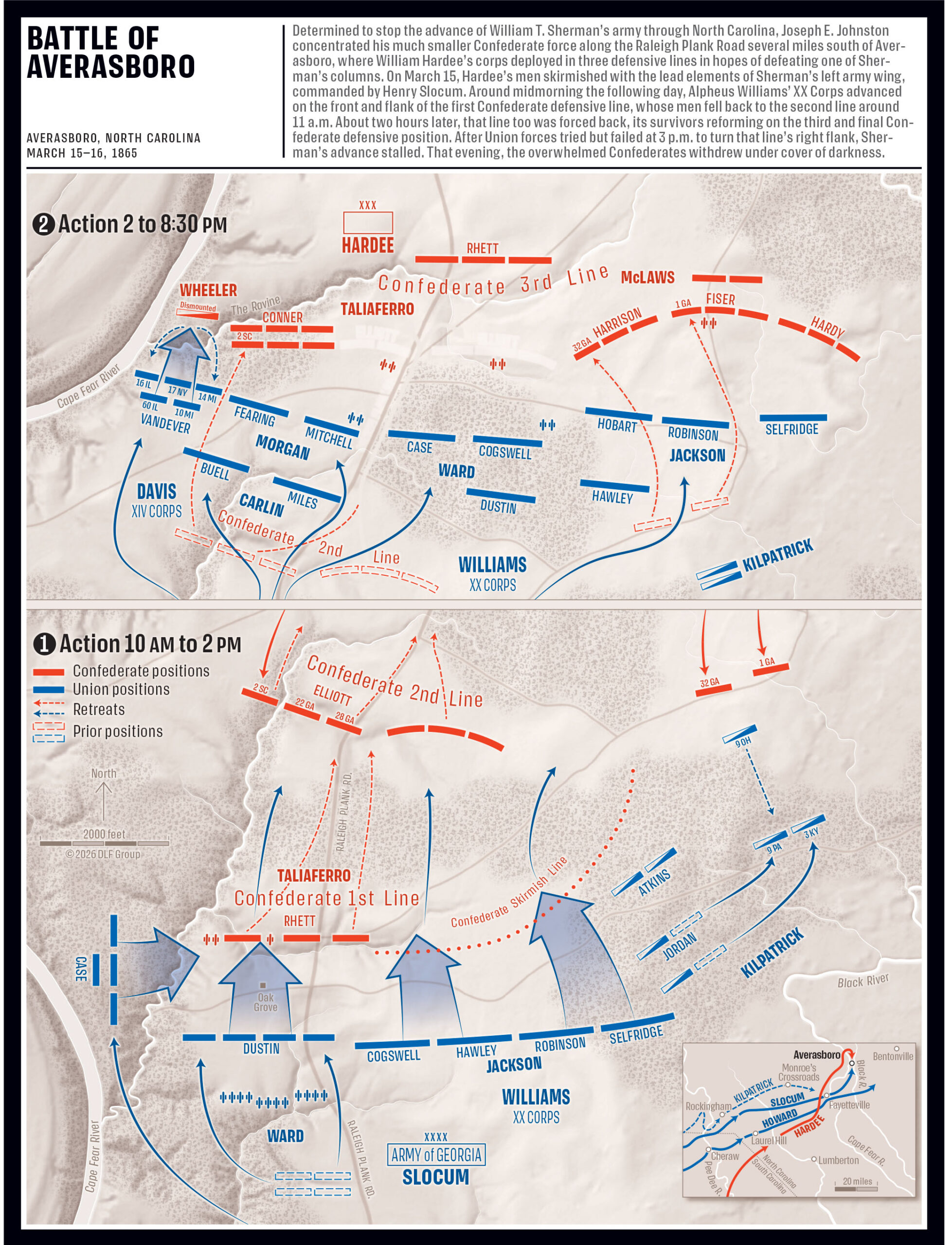

On the afternoon of March 15, 1865, Union cavalrymen plodding along a rural North Carolina road were shot at by enemy skirmishers posted in the rain-drenched woods and fields ahead of them. Behind them, the left wing of Major General William T. Sherman’s vaunted army had been on the march with little interruption since leaving Savannah and entering South Carolina almost two months earlier. Near the farming village of Averasboro, this would change, as the Rebels finally made their first major attempt to blunt Sherman’s trek through the Carolinas.

The Confederacy was dying, General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia stagnant and starving in the Petersburg-Richmond defenses. Sherman had burned a destructive path through South Carolina, and Rebel forces in the West were beaten, weak, and scattered. North Carolina was a microcosm of southern misery that early spring. The fall of Wilmington—the Confederacy’s last seaport—on February 22 felt like a salted wound as Sherman’s army bore into the state.

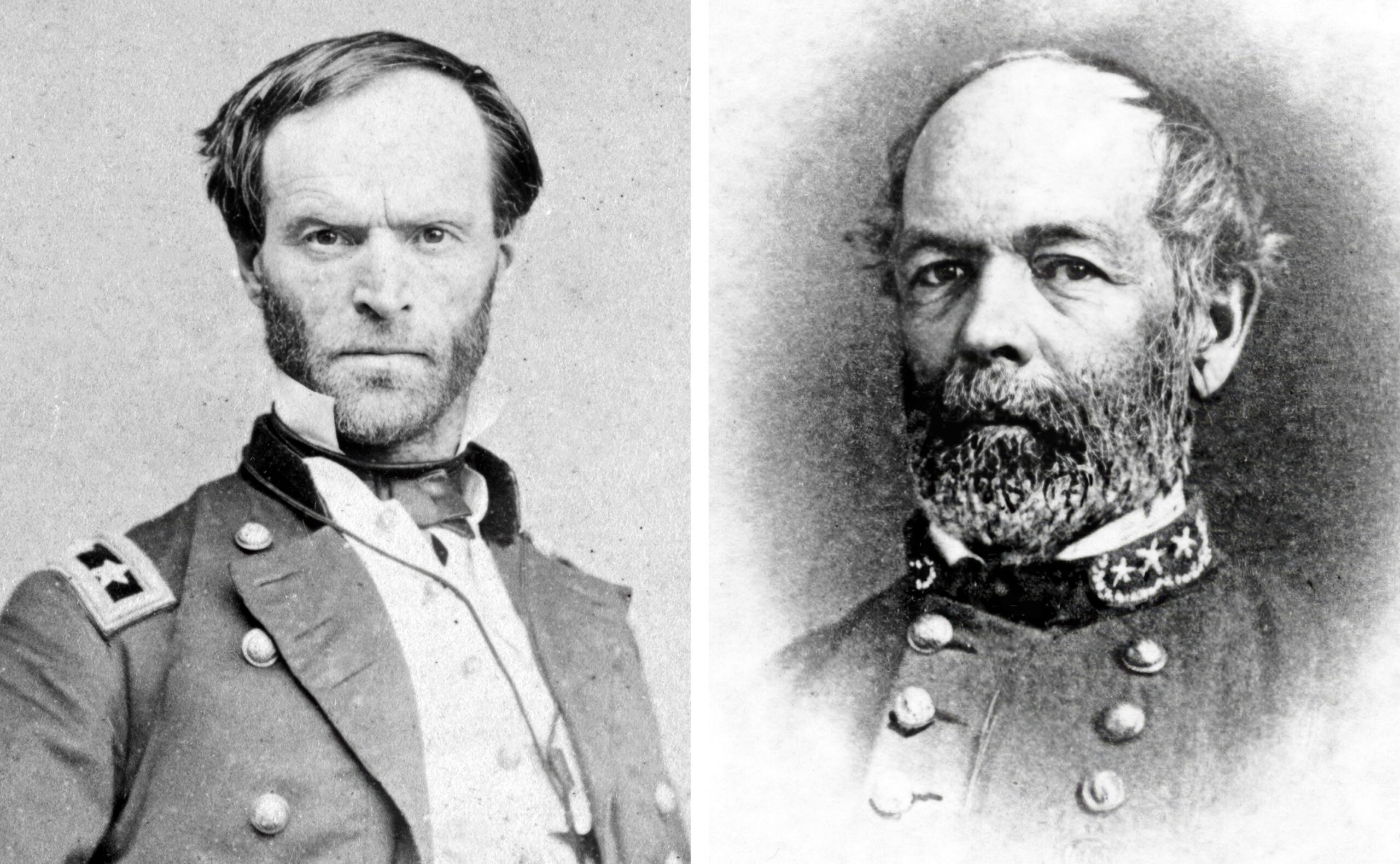

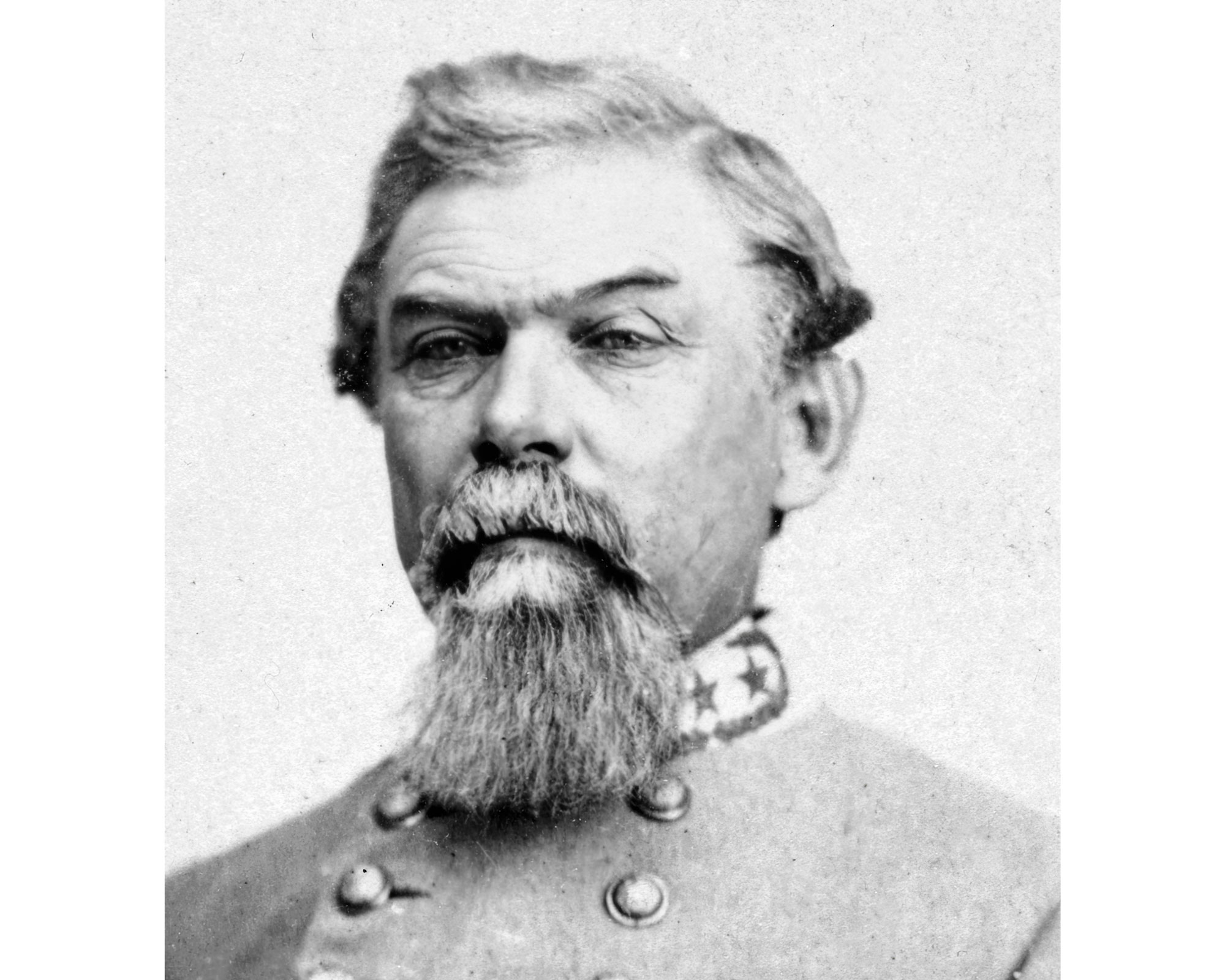

Library of Congress (Sherman); South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina

Library of Congress (Sherman); South Caroliniana Library, University of South CarolinaWilliam T. Sherman (left) and Joseph E. Johnston

That army consisted of about 60,000 veterans, men who had fought from Chattanooga through Georgia’s mountain wilds to seize Atlanta and then embarked on the epic March to the Sea, climaxing with Savannah’s capture on December 21, 1864. After resting and refitting there, Sherman had plunged northward in the new year. Beyond punishing South Carolina, which he and many other northerners considered the nest of secession, Sherman intended to keep marching, destroying railroads and other key installations en route to joining Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia for what both men hoped would be the war’s final campaign. Divided into two wings, his army feinted toward Augusta, Georgia, and Charleston, drawing Rebel units to those points and away from the Yankees’ intended route through the heart of the state. Columbia fell to Sherman on February 17, 1865, much of South Carolina’s capital going up in flames that night, each side blaming the other for the conflagration.

Early March found the Yanks slashing into North Carolina. Major General Henry Slocum commanded the left wing of Sherman’s army, composed of the XX Corps, led by Brigadier General Alpheus Williams, and Brevet Major General Jefferson Davis’ XIV Corps. Major General Oliver Howard headed the army’s right wing, consisting of Major General John Logan’s XV Corps and Major General Frank Blair’s XVII Corps. Sherman’s 5,600 cavalrymen were led by Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick. The approximately 30,000 troops in each wing, plus their supply wagons, artillery, and ambulances, necessitated that they move on different roads, usually several miles apart but always in the same general direction.

It was about this time that Sherman learned that his old opponent from the Atlanta Campaign, General Joseph E. Johnston, was facing him again. Now, Johnston had orders from Lee to try to block Sherman’s advance. Johnston was to reassume command of what was left of the Army of Tennessee as well as scattered troops in the Confederate Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, assemble them, and stop Sherman. A few days after Lee’s February 22 directive, all Rebel troops in North Carolina also were placed under Johnston’s authority.

Johnston was in Charlotte on February 25 when he issued his first general orders to his new command. He wrote that he had “strong hope” and urged “all absent soldiers of the Army of Tennessee to rejoin their regiments and again confront the enemy they so often encountered in Northern Georgia, and always with honor.” Johnston began to concentrate his force in North Carolina, hoping to pounce on one of Sherman’s wings, since he was not strong enough to tackle the entire army.

By March 8, all of Sherman’s army had entered North Carolina, its immediate goal to capture Fayetteville and Goldsboro, both important railroad and industrial centers. Plodding north a few miles ahead of the Yankees was the enemy. A Confederate corps commanded by Lieutenant General William J. Hardee had evacuated Charleston with the rest of the Rebel garrison on February 18 and was retreating before Slocum’s troops. Hardee had started from Charleston with about 13,000 men, but by early March widespread straggling and desertion had whittled his force to about 6,400. Supporting Hardee were some 5,000 cavalrymen under Major General Joseph Wheeler. Short on rations, the outnumbered Rebs “ate parched corn, pickled pork, roots, grub worms—anything they could swallow,” one soldier recalled.1

Hardee reached Fayetteville on March 9, but he couldn’t hold it. Two days later, civilian officials surrendered the town to Sherman, Hardee’s men having withdrawn across the Cape Fear River, burning the bridge behind them. The Confederates were unsure of Sherman’s next move. Would he strike for Goldsboro or Raleigh? Johnston decided to marshal his troops at Smithfield, a town about halfway between the two, and await developments.

Richland County Public Library, Columbia, SC

Richland County Public Library, Columbia, SCBefore it entered North Carolina, Sherman’s 60,000-man army had carved a destructive path through that state’s southern neighbor. Above: A depiction of the burning of Columbia, South Carolina, on February 17–18, 1865, for which neither side claimed responsibility.

Lee wanted Johnston to be as aggressive as practical in battling Sherman, but informed him on March 15, “a disaster to your army will not improve my condition,” adding that, “I would not recommend you to engage in a general battle without a reasonable prospect of success.” Lee also stated that Johnston and an independent force under General Braxton Bragg should look for an opportunity “to unite upon one of their [Sherman’s] columns and crush it.”2

By March 15, Sherman was across the Cape Fear River and menacing Goldsboro, some 70 miles from Fayetteville. He planned to feint toward Raleigh and turn toward Goldsboro with both wings. There the army could rest and resupply before continuing its march toward Richmond. Sherman knew that Johnston was massing somewhere ahead of him, yet he remained confident. “The enemy is superior to me in cavalry, but I can beat his infantry man for man, and I don’t think he can bring 40,000 men to battle,” he wrote Grant on March 14. “Keep all parts busy and I will give the enemy no rest.” Still, Sherman was more cautious and battle-ready when his columns left Fayetteville.3

Kilpatrick’s cavalry was sent northeast up the Raleigh Plank Road toward Averasboro, followed by four divisions of Slocum’s left wing and a few wagons. The rest of the baggage train, accompanied by the left wing’s two other divisions, was to take a shorter route toward Goldsboro, some 60 miles distant. Sherman also instructed Howard to have four divisions from the right wing ready to move to Slocum’s assistance if the latter was attacked.

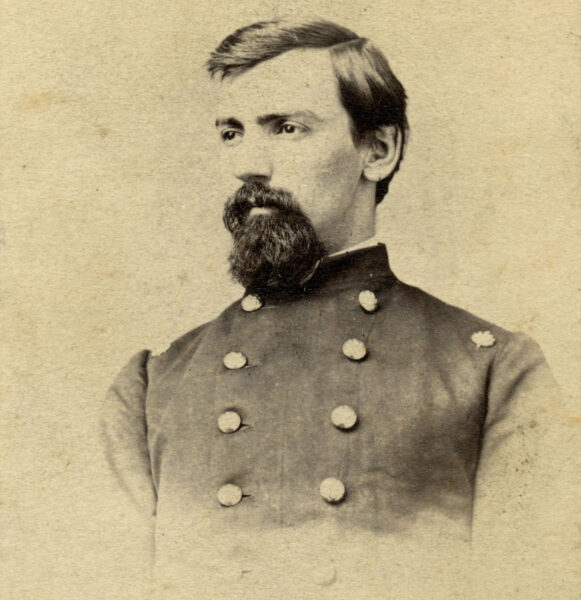

Johnston, meanwhile, had posted Wheeler on the Raleigh Plank Road while the rest of his cavalry protected the Goldsboro route. Hardee was ordered to continue shadowing the Union force advancing up the Raleigh Plank Road, blocking its advance if possible. Kilpatrick’s men sparred with Wheeler’s troops and shoved them back on the afternoon of March 15. About 3 p.m., however, Kilpatrick’s Second Brigade, commanded by Brevet Brigadier General Smith Atkins, smacked into Rebel skirmishers defending the road near the rural community of Smithville (not to be confused with Smithfield), some five miles south of Averasboro. These Confederates belonged to Colonel Alfred Rhett’s brigade in Brigadier General William Taliaferro’s division of Hardee’s corps and were mostly coastal artillerymen or garrison troops fighting for the first time as infantry.

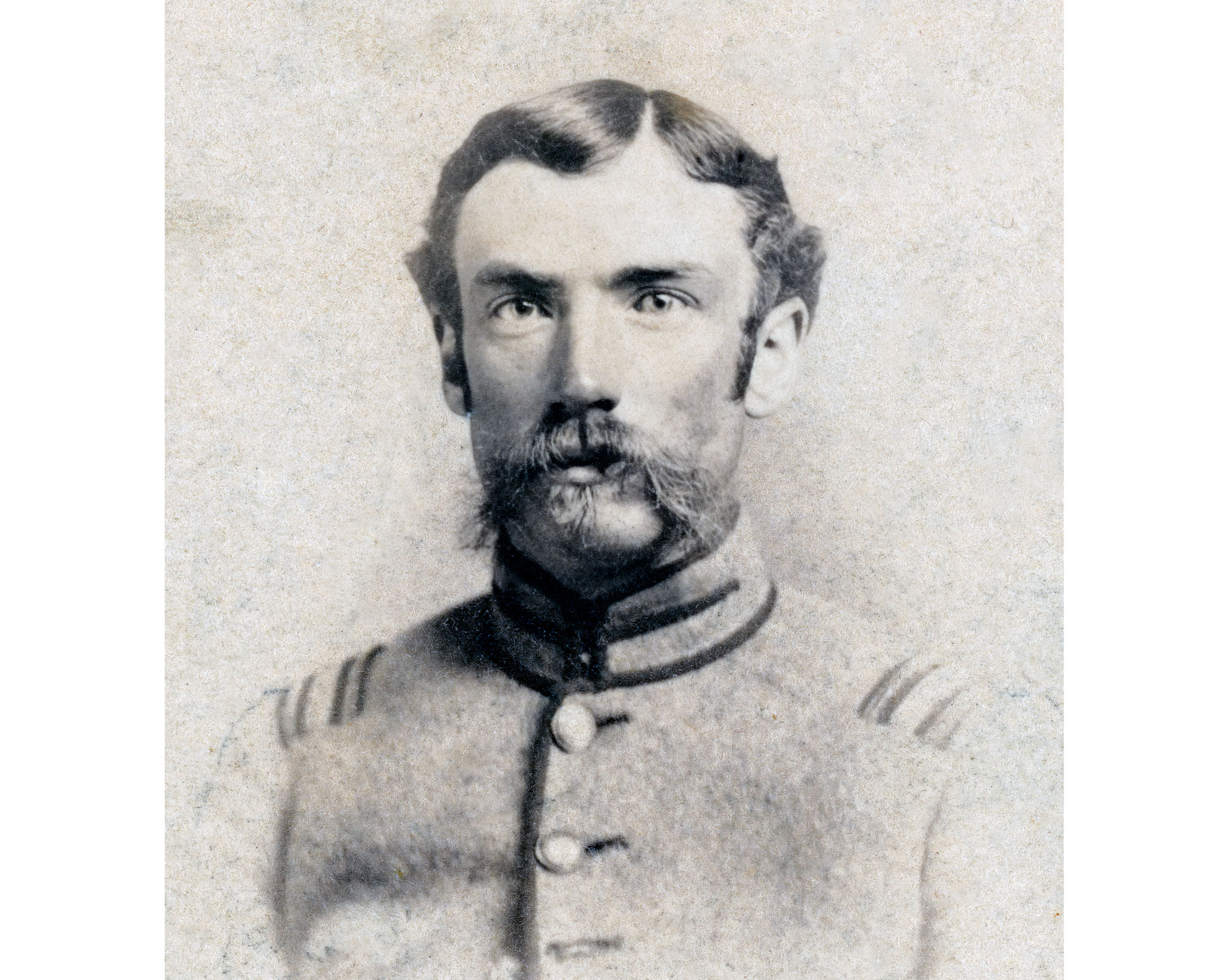

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAmong the Confederates engaged at Averasboro was Colonel Alfred Rhett (above), a member of the fire-eating Rhett family of Charleston whose brigade held the first of three Confederate defensive lines.

Hardee had decided to make a stand. His corps, consisting of Taliaferro’s men and a division commanded by Major General Lafayette McLaws, a veteran of the Virginia campaigns, had been encamped near Smithville and intent on a day’s rest. The Union threat, however, forced Hardee to make a choice: He could continue to fall back or he could fight and determine if he was being followed by all or only a portion of Sherman’s army. Nicknamed “Old Reliable,” the Georgian was a career soldier who had seen much action in the war’s western campaigns, and had faced Sherman at Shiloh, Atlanta, and Savannah. A South Carolinian who fought at Averasboro remembered Hardee as “a courtly and knightly soldier, and a great favorite with the men.”4

Hardee dug in on a narrow neck of land between the Cape Fear and Black rivers at Smithville, blocking the Raleigh Plank Road. The surrounding landscape was a patchwork of farm fields, swamps, and thickets, all saturated by recent rains. Presiding over the countryside were three plantation homes of the Smith family: “Lebanon,” the Farquhard Smith house, where 18-year-old Janie Smith would experience the war’s horrors firsthand; the William Turner Smith residence; and “Oak Grove,” built in the 1790s by the John Smith family. All three houses would soon become field hospitals, crammed with wounded from both sides.

Hardee placed his troops in three lines, putting his greenest soldiers in the first and second positions while McLaws’ veterans occupied the third. Rhett’s men held the first line, posted on both sides of the Raleigh Plank Road and about 400 yards north of Oak Grove. Most of these Rebels entrenched along a field on the right, the position extending across the road into some woods. They built makeshift breastworks “as the scanty means at my command permitted,” reported Taliaferro, who also brought up three cannons, which were positioned on the extreme right of Rhett’s line. Taliaferro’s other brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Stephen Elliott Jr., composed the second line, positioned to the rear of swampy land some 200 yards behind Rhett. McLaws’ third line was located some 600 yards behind Elliott.5

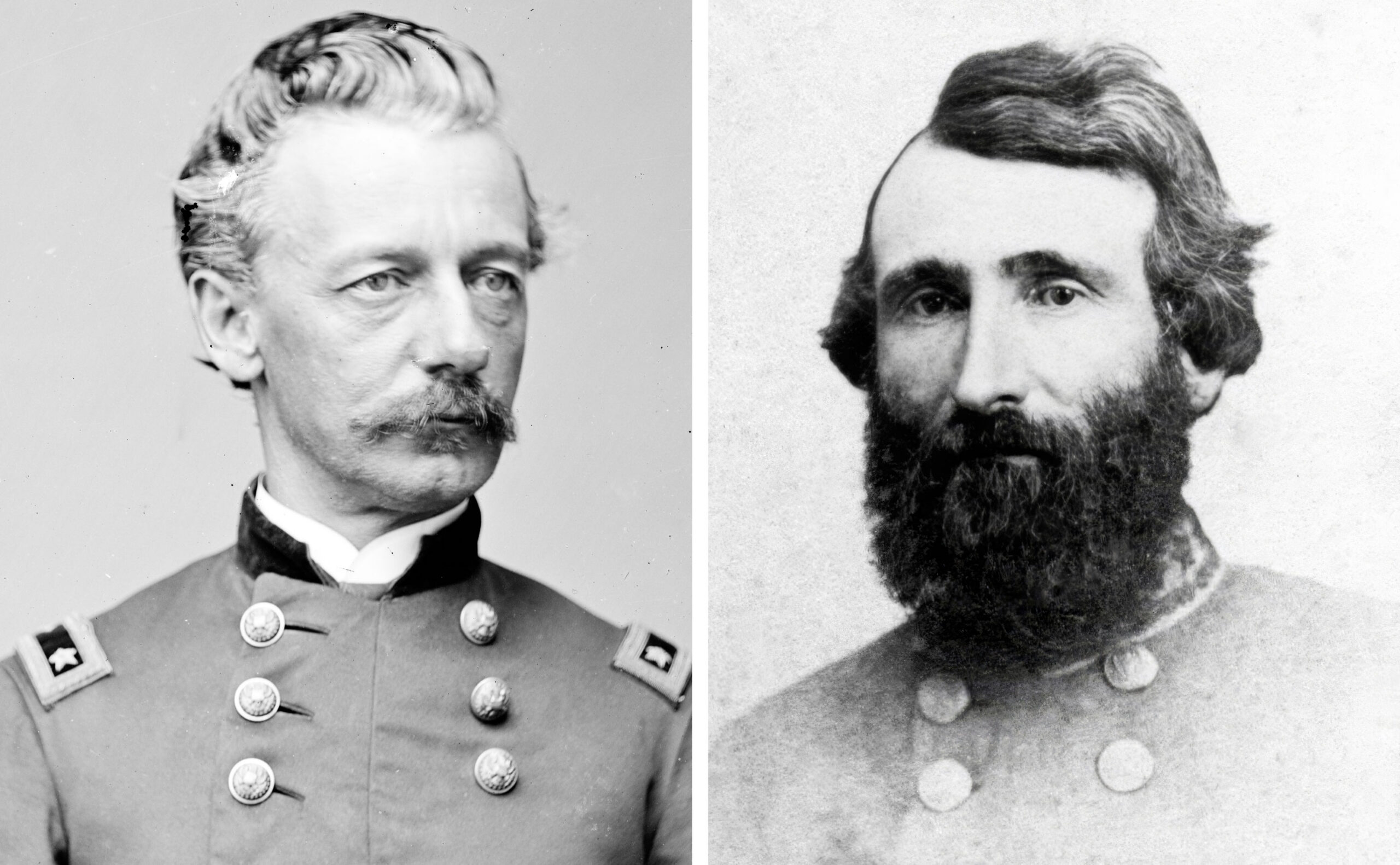

Library of Congress (Slocum); South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina

Library of Congress (Slocum); South Caroliniana Library, University of South CarolinaHenry Slocum (left) and William Taliaferro

Rhett was a member of the fire-eating Rhett family of Charleston who had stoked the secession blaze during the Confederacy’s infancy. Indeed, his father, Robert Barnwell Rhett, was considered by many to have sired the disunion movement, and the younger Rhett had commanded Fort Sumter for a time, meaning that both men were well known in the North. Rhett’s brigade included the 1st Regiment, South Carolina Regular Artillery, which had endured bombardments by Union warships and field guns while posted in the Charleston defenses. “The regulars were very particular as to the good appearance of their guns, their dress, and everything appertaining to them,” a southern young woman wrote of them, “those who were disposed to be critical, even called them dandies.” Lugging muskets and packs and on the miserable march since Charleston’s evacuation a month earlier, these “dandies” were now hunkered in the mud, yet no less resolved to fight.6

Rhett’s skirmishers clashed with Atkins’ lead regiment, the 9th Michigan Cavalry. With the superior firepower of their Spencer repeating carbines, the Michiganders were able to push Rhett’s skirmishers back to their breastworks. Confederate artillery opened on the bluecoats at this point, however, and Kilpatrick sent in the rest of Atkins’ brigade, which dug in on each side of the road. Sniping continued until dark when heavy rain drenched the foes.

Slocum ordered a XX Corps brigade to bolster the cavalry in their hastily prepared defenses. These men, Colonel William Hawley’s command in Brigadier General Nathaniel Jackson’s First Division, received the order to move about 7:30 p.m. They hurried ahead by torchlight as best they could through the muck, enduring a miserable five-mile march. Sometime after midnight, they filtered into position in the center of the cavalry line, relieving Atkins’ troops.

Rhett, meanwhile, had been captured late that afternoon by the Yankees in a most embarrassing manner. Seeing some cavalrymen he believed to be from Wheeler’s command in a ravine to his front, he and an aide had ridden out to communicate with them. In reality, the unidentified riders were Union troopers, disguised as Rebels and led by Captain Theo Northrop, Kilpatrick’s chief scout. The captain pointed a pistol in Rhett’s face and told him, “You must come with me.” Replying, “Who the hell are you?” Rhett drew his revolver, but was quickly staring into the barrels of several carbines. The flustered Rebs were hustled to the Union rear, word of Rhett’s capture spreading quickly through the Federal ranks. “He was dressed in a new uniform and was as clean as a new pin,” remembered W.H. Morris of the 10th Ohio Cavalry. “He had on a very fine pair of patent leather boots, and the boys said they were so small that none of us could get them on.”7

Rhett was taken to Slocum, who had known him from prewar days when Slocum was posted at Charleston. Rhett was “handsomely dressed in the Confederate uniform, with a pair of high boots beautifully stitched,” Slocum related. “He was deeply mortified at having been ‘gobbled up’ without a chance to fight.” Sherman, who was traveling with Slocum’s wing at the time, also encountered Rhett, describing him as “a tall, slender, and handsome young man,” who was “dreadfully mortified to find himself a prisoner in our hands.” Sherman and Blair, who also was present, “were much amused at Rhett’s outspoken disgust at having been captured,” the colonel freely telling his captors that his men were garrison artillerymen who “had little experience in woodcraft.” Slocum recalled that Rhett spent the night in his tent and they had “a long chat over old times and about common acquaintances in Charleston.” In the morning, Rhett was turned over to the provost guard, which had orders to treat him “with due respect” and give him a horse to ride.8

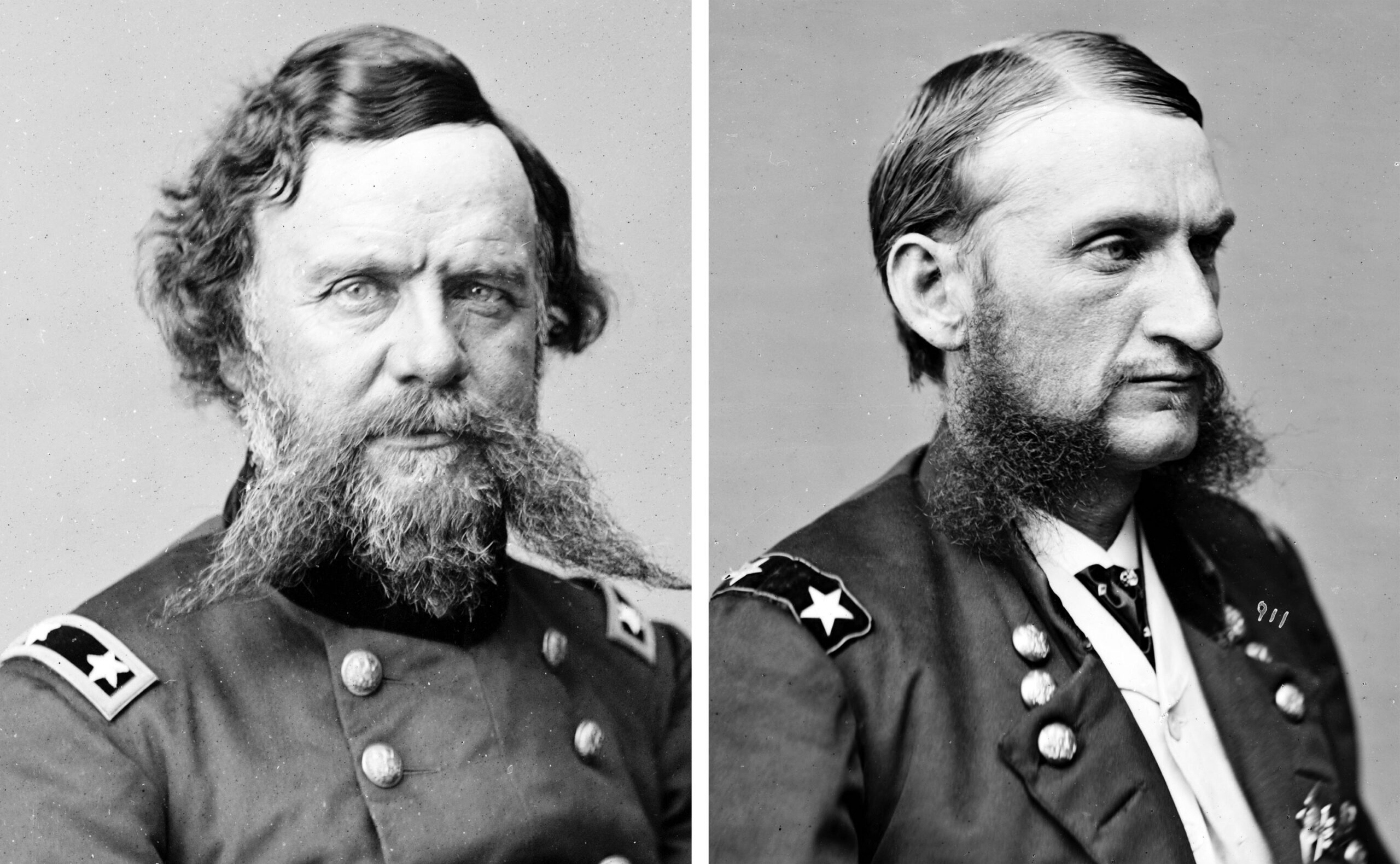

Library of Congress (2)

Library of Congress (2)Alpheus Williams (left) and Judson Kilpatrick

There was little firing overnight, the enemies content to rest and gird for the coming battle. Both sides were entertained by the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry’s regimental band in Hawley’s command, which played when the rain slackened. In the Confederate defenses, Colonel William B. Butler had assumed command of Rhett’s brigade, his soldiers cooking a meager ration of cornmeal and bacon, eating some and saving the rest for the next day. Hardee, meanwhile, had ordered Taliaferro to hold the first line “until it was no longer tenable” and then fall back on Elliott. The Confederates would man this second line as long as possible before retiring to Hardee’s extended main defenses, where McLaws’ division waited. Overnight, Sherman issued several orders about the expected battle. He wrote to Howard—whose right wing was a few miles away—about 2 a.m. on March 16: “Hardee’s whole force is in our front near the forks of the road, and I have ordered Slocum to go at him in the morning in good shape but vigorously and push him beyond Averasboro.” He added, “I think Hardee will try and fight us at the cross-roads,” and also mentioned Rhett’s capture. “Hardee is ahead of me and shows fight. I will go at him in the morning with four divisions and push him,” he noted in another dispatch.9

About 6 a.m., the 8th Indiana Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel F.A. Jones, drove in Wheeler’s pickets before tangling with Taliaferro’s skirmishers on the right side of the Federal line east of the Raleigh Plank Road. Captain Thomas A. Huguenin of the 1st South Carolina Infantry, who had been the last Rebel commander at Fort Sumter before Charleston fell, led the skirmish line. The captain exhibited “conspicuous coolness” this day, recalled Arthur Ford, a soldier in Rhett’s brigade. “During the hardest of the fighting he walked slowly immediately behind the line … smoking his pipe as calmly as if he had been at home.”10

Jones’ dismounted troops met with initial success, primarily due to the intensity of their seven-shot Spencer carbines, but Butler deployed more skirmishers as the combat crackled over the gloomy landscape. Soon outnumbered, Jones retreated, his brigade commander, Colonel Thomas Jordan, sending the 9th Pennsylvania and the 2nd and 3rd Kentucky cavalry regiments to solidify the position. Jordan’s brigade repelled several enemy thrusts as the fighting intensified in this area, and Kilpatrick hurried forward Atkins’ brigade for more support.

Williams, the XX Corps commander, received word from Kilpatrick about 7:30 a.m. that Rebels still opposed him in force. He immediately ordered Brigadier General William Ward to march his Third Division to this danger point, followed by the other two brigades of Jackson’s division, Hawley’s brigade being already at the front. Lead elements of Ward’s units reached the rear of Hawley’s position about 9:30 a.m. after a five-mile march. Ward was ordered to relieve Hawley’s troops, who had been on duty through the night and engaged in severe skirmishing to that point in the morning. “It was a wretched place for a fight,” related Captain Daniel Oakey of the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry. “At some points we had to support our wounded until they could be carried off, to prevent their falling into the swamp water, in which we stood ankle deep.”11

Ward pushed his division into position on the left, Jackson’s other brigades going into line on Hawley’s right, facing north on both sides of the Raleigh Plank Road by early afternoon.12 As these units aligned for battle, the 10th Wisconsin Battery, commanded by Lieutenant E.W. Fowler and assigned to Kilpatrick’s calvary, dueled with the enemy cannoneers, rounds howling both ways over the fields around Oak Grove. Fowler’s gunners encountered artillery fire as they unlimbered on a rise in a field some 1,500 yards from the Confederate earthworks. “I commenced firing with singularly good effect as reported by prisoners taken,” Fowler related. The Federal line soon advanced to within a few hundred yards of Butler’s defenders, concentrating on his main position north of Oak Grove. Colonel Daniel Dustin’s brigade was in the immediate front of these works, three of his four regiments exposed to cannon fire as they lay in open fields south of the house, the fourth deployed in woods.

The battle in this sector, however, was about to shift in favor of the bluecoats. Three batteries commanded by Major John Reynolds, the XX Corps artillery chief, arrived sometime midmorning, relieving Fowler’s battery and unlimbering on a gentle elevation within 500 yards of the Rebel defenses. At this short range, they unleashed a hellish fire on the enemy guns, exploding a limber, disabling artillery horses, and ripping the crest of the enemy rifle pits, killing and wounding a number of Confederates. “The practice of these batteries was very superior,” Williams related; Taliaferro noted that the Union cannon “shelled our lines with great determination and vigor….”13

Harper’s Weekly

Harper’s WeeklyThis illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicts Union artillery and infantry, positioned on either side of Raleigh Plank Road, engaging with entrenched Confederates during the Battle of Averasboro.

Sherman was on the field by now, issuing orders about 10:30 a.m. that a brigade should be sent wide to the left to flank Butler. Williams ordered Colonel Henry Case’s brigade to make the attempt, Case having to pull his troops out of line, march behind Dustin’s position, and plunge into the swamps and thickets west of Oak Grove. Hindered by thick underbrush, Case’s men encountered enemy skirmishers, scattering them before they could warn Butler’s main force. Case himself went forward to reconnoiter and soon found himself looking down the unsuspecting right flank of Butler’s position about 300 yards away. He quickly returned to his men and prepared to attack. The 102nd Illinois and 79th Ohio infantry regiments led the assault minutes later with the 129th and 105th Illinois in support. “The men sprang forward with alacrity, with a deafening yell,” Case recalled, the Illini and Ohioans roiling out of the woods to unload “a destructive fire” on the startled Rebels. “So sudden and so desperate was the charge that the enemy … fled precipitately in the utmost confusion….” The Carolinians frantically tried to save their cannon, mired in the mud, but the Yanks were too near and too many, shooting artillery horses and overwhelming gunners amid the chaos. “In vain the enemy resisted,” stated Lieutenant Colonel Azariah Doan of the 79th Ohio, “in vain he labored to get his artillery off the field.” Case effectively crumpled Butler’s line, “driving the rebels out at a run,” Williams reported.14

During Case’s flank attack, Dustin launched a frontal assault in support, his men charging into the teeth of heavy musketry. While Dustin’s 33rd Indiana and 22nd Wisconsin infantry regiments were sheltered somewhat from this lethal fire by the Oak Grove house and its outbuildings, his 85th Indiana and 19th Michigan advanced over open ground. Dustin executed a left oblique so that these latter regiments were also given some cover by the structures. From the farm, Dustin’s men sustained a brisk return fire and continued the onslaught, his skirmishers and the 19th Michigan being first into the enemy works, where they linked up with Case’s men. “The enemy fled in great confusion,” reported Ward, who also reported his division captured Butler’s three artillery pieces and 100 prisoners, not including 68 wounded men scattered in the defenses. Soldiers of the 105th Illinois assisted Reynolds’ gunners in turning the captured guns against the Confederates, “giving them half a dozen shots in their retreating ranks,” an officer recorded. “The ground was thickly strewn with the enemy’s dead and wounded,” related Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Flynn of the 129th Illinois. “The prisoners were so numerous that they were simply ordered to the rear without a guard.”15

Under this duress, Taliaferro ordered a withdrawal to Elliott’s second line about 11 a.m. “The fighting was severe during the entire morning, and men, as well as officers, displayed signal gallantry,” he wrote. “Our loss was heavy, including some of our best officers.” Trudging across this hard-won terrain, Captain Oakey paused over a slain Confederate, “a very young officer, whose handsome refined face attracted my attention.” Oakey knelt by him for a moment. “His buttons bore the arms of South Carolina. Evidently, we were fighting the Charleston chivalry.”16

While the Federals in this sector rested and regrouped after the assault, a clatter of musketry signaled trouble on the far right. Colonel James Selfridge’s brigade of Jackson’s division, which had been guarding a wagon train well to the rear, finally reached the action about 12:30 p.m., going in to line to the right of Robinson’s command. Filtering through the trees to link with Kilpatrick’s cavalry, which was still on the extreme right, they were startled to see Union troopers suddenly crashing to the rear in confusion. These were elements of Jordan’s brigade, which had been surprised by a small force of Butler’s southerners. Now it was the turn of these Confederates to be shocked, as they burst out of marshy woods less than 100 yards from Selfridge’s infantry. The Rebels were “met by a simultaneous volley from the whole brigade” that was “evidently unexpected,” related Colonel James Rogers of the 123rd New York Infantry. The massed musketry caused the Rebs to retreat in disorder. Selfridge reported that 40 dead Confederates were later buried in front of his brigade.

Hardee, meanwhile, had already sent a dispatch to Lieutenant General Wade Hampton, Wheeler’s superior, when he fired off another message to the cavalry chief at 11:30 a.m. In the latter communication, he stated that “the enemy attacked me this morning … and we have been fighting him ever since. Rhett’s brigade fell back in some disorder, but rallied on Elliott. My principal fight will be at this point, where McLaws has his entire division…. Unless the enemy brings up a heavier force than he has yet shown, I have no doubt of my ability to hold my position till night, when I shall retire, in obedience to what I regard as General Johnston’s wishes….”17

The divisions of Ward and Jackson, along with Kilpatrick’s cavalry, pressed forward about 1 p.m., testing the Confederates’ second line where Elliott’s brigade and Butler’s survivors were dug in astride the Raleigh Plank Road. Federal cavalry scouts soon reported finding a road behind the Confederate left flank, and Kilpatrick sent Colonel William Hamilton’s 9th Ohio Cavalry of Atkins’ brigade to occupy it and outflank the enemy. Hamilton’s horsemen rumbled out, despite being low in ammunition. Shortly thereafter, McLaws, whose third line was strung much wider than Elliott’s, was alerted that enemy cavalry was menacing Elliott’s left. McLaws immediately ordered two of his infantry regiments—the 32nd Georgia of Colonel George Harrison’s brigade and the 1st Georgia Regulars of Colonel John Fiser’s

brigade—to meet this threat. The Ohioans were moving in column through an opening in the swamp to reach the road when they banged into these Rebels, unseen in the dense woods, about 1:30 p.m. The southerners “opened a most murderous fire,” one Union officer wrote, pushing back Hamilton’s horsemen and pursuing them. Hamilton rallied on high ground some 200 yards to the rear and, aided by troopers of the 9th Pennsylvania and 2nd Kentucky cavalry regiments of Jordan’s brigade, commenced fire of their own, repelling the threat.18

Concerned about Elliott’s right flank, McLaws earlier had dispatched the 2nd South Carolina to that point. It was not enough, however, as Ward and Jackson continued forward with overwhelming numbers. Even as McLaws’ two regiments were fighting the Union cavalry, Taliaferro, faced with the enemy’s “immense superiority in numbers,” ordered his division to fall back to McLaws’ main line about 1 p.m. His division withdrew “with no difficulty and little loss,” the 2nd South Carolina serving as rear guard. At this point, Hardee had about 8,000 men to hold off the approximately 20,000 Federals on the field.19

Library of Congress

Library of CongressThe day after the battle, William J. Hardee (above) offered his defeated men his thanks “for their courage and conduct of yesterday, and congratulates them upon giving the enemy the first serious check he has received since leaving Atlanta.”

A light rain that had fallen much of the day added to the already slow troop movements as more Federals tried to reach the action. Brigadier General James Morgan’s XIV Corps division arrived by early afternoon and went into position on the left of Ward’s division. Morgan was intent on turning Hardee’s right flank, but he was unaware that the Confederate defenses had been extended almost to the river by Wheeler’s cavalrymen. About 3 p.m., Morgan sent Brevet Brigadier General Benjamin Fearing’s brigade on this end run, and the Midwesterners were confounded to find an enemy battle line in the dank woods. Fearing sent Morgan word of this obstacle, but Morgan had advanced his First Brigade, led by Brigadier General William Vandever—who was to go in on Fearing’s left and try to get around the Rebel right—before he received the message. Impeded by tough terrain, Vandever’s five regiments labored forward, only to be halted by a stout fire from Wheeler’s troopers. Morgan promptly recalled Vandever’s brigade, later stating that “it would have been worse than folly to have attempted a farther advance.”20 Late in the afternoon, Hardee sent word to Johnston that he had stalled the Union advance and that he would retreat toward Smithfield after nightfall.

Like Oak Grove, the two other Smith homes were now clogged with wounded soldiers. At “Lebanon,” which was still in Confederate hands, Janie Smith was kept busy making bandages and offering food or water to these men. Writing on scraps of wallpaper and book fly leaves, she described the awful scene in an April 12 letter to a friend. “One half of the house was prepared for the soldiers … but every barn and out house was filled, and under every shed and tree the tables were carried for amputating the limbs,” she wrote. “I just felt my heart would break when I would see our brave men rushing into the battle and then coming back so mangled. The scene beggers description, the blood lay in puddles in the grove, the groans of the dying and the complaints of those undergoing amputation was horrible, the painful impression has seared my very heart.” The horrors were little different at the William Smith home a mile or so to the south, where Union forces established a field hospital. The family piano was used as an operating table and some dead were buried in the garden. Janie Smith wrote that this house, occupied by her widowed Aunt Mary and her four daughters during the battle, “is ruined with the blood of the Yankee wounded.”21

Heavy skirmishing occurred along the last Confederate line after nightfall, even as the Rebel artillery pulled back. Hardee’s infantry followed, beginning about 8 p.m., leaving campfires burning to try to deceive the Federals. There was sporadic fighting into the early morning of March 17 as some of Wheeler’s troopers covered the Confederate withdrawal, fighting dismounted among Hardee’s abandoned earthworks until almost sunrise. Janie Smith wrote that Wheeler himself “took tea” at her home about 2 a.m. before joining the retreat. “We held our position until about midnight when we fell back,” related the Rebel Arthur Ford. “This night’s march was a very trying one. The road was terribly cut up by the wagons and artillery, and as the rains had been frequent it seemed as if the clay mud was knee deep.”22

Hardee was some five miles north of Averasboro about 1 a.m. when he dispatched another message to Johnston regarding the battle. He reported losses of “between 400 and 500” and added, “Enemy’s loss not known but believed to be heavy.” Some of the exhausted Confederate units were halted about dawn and finally fed. “We floundered along for about six hours, and at daylight … were given some rations,” Ford remembered. “Most of us had not had a morsel of food since the night of the 15th.” The Federals realized the Confederates were gone well before sunup and followed in pursuit—Kilpatrick’s cavalry and Ward’s infantry in the lead—finding the four miles of road to Averasboro strewn with the carnage of Hardee’s exodus. There was “evidence of great haste on the part of the retreating rebels, who abandoned wagons, ambulances containing their wounded, and left a portion of their wounded on the field and in the adjoining houses without surgical attendance,” recalled Lieutenant Colonel Philo Buckingham of the 20th Connecticut Infantry, part of Ward’s division. Amid the battlefield gore lay seriously wounded Captain Armand DeRosset of the 2nd North Carolina Infantry Battalion, one of six brothers in Confederate service. He survived, and in later years credited a Union surgeon for saving his life.23

Hardee’s battered corps reached the hamlet of Elevation shortly after noon on March 17, where the general issued orders commending his soldiers for their mettle at Averasboro. He offered thanks “for their courage and conduct of yesterday, and congratulates them upon giving the enemy the first serious check he has received since leaving Atlanta.” Hardee told the men they had faced three times their number, which was basically true, but his casualty totals were wildly inaccurate, whether by design to bolster morale or just due to bad information: He claimed the corps had lost fewer than 500 men while inflicting some 3,300 casualties. “The lieutenant-general augurs happily of the future service and reputation of troops who have signalized the opening of the campaign by admirable steadiness, endurance, and courage,” Hardee closed. At Smithfield that morning, Johnston sent word of the Averasboro battle to Lee. “He [Hardee] was repeatedly attacked during the day … but always repulsed him [the enemy].” Hardee had stymied the advance of one of Sherman’s wings for about 36 hours and had paid for it. The 1st South Carolina Artillery of Rhett’s brigade suffered 215 casualties, almost half of its strength. Union losses were set at 682, including 95 dead, 500 wounded, and about 50 missing or captured.24

At Oak Grove, Union physicians treated about 70 Confederate wounded before leaving them in the care of an officer and several prisoners. Sherman “visited this house while the surgeons were at work, with arms and legs lying around loose, in the yard and on the porch,” he later wrote. Inside, he encountered a young Rebel, Captain J.R. Macbeth, whose left arm had just been amputated. Sherman had been acquainted with the Macbeths while posted at Charleston before the war. “I inquired about his family, and enabled him to write a note to his mother,” Sherman remembered, adding that the letter was mailed a few days later. Taliaferro wrote that his men “fought admirably” despite their inexperience. “Although unaccustomed to field fighting, they behaved as well as any troops could have done. The discipline of garrison service, and of regular organizations, as well as their daily exposure for eighteen months past to the heavy artillery of the enemy, told in the coolness and determination with which they received and returned the heavy fire of this day.”25

Hardee’s stand not only bought time for Johnston, it also served to further separate Sherman’s army, since Howard’s right wing had continued its march while Slocum’s troops fought at Averasboro. Presented with this opportunity, Johnston struck Slocum at Bentonville, about 20 miles north of Averasboro, on March 18-21, with Hardee’s corps among the 21,000 Confederates engaged. The battle was the largest fought in North Carolina during the war, but its 4,200 total casualties accomplished little other than to halt half of Sherman’s army for a few days more and further bleed the Confederates. Hardee’s 16-year-old son, Willie, was among the slain.

Just as much a part of the story is the encounter of one of Slocum’s officers, who happened upon the cavalier Colonel Rhett plodding along as a prisoner, without his fine boots, shortly after the fight at Averasboro. Believing that Rhett had earlier mistreated some of his captured men, Kilpatrick had taken his horse. As for his splendid footwear, a “soldier had exchanged a very coarse pair of army shoes for them,” Slocum stated. “Rhett said that in all his troubles he had one consolation, that of knowing that no one of Sherman’s men could get on those boots.”26

Sherman and Johnston continued to spar before Johnston, knowing Lee had surrendered more than two weeks earlier, capitulated near present-day Durham on April 26. Averasboro was thus soon forgotten, the pageantry and agony of Appomattox and President Lincoln’s assassination headlining the American saga in the spring of 1865.

Derek Smith has written a number of books on the Civil War, including Lee’s Last Stand: Sailor’s Creek, Virginia, 1865 (2004) and In the Lion’s Mouth: Hood’s Tragic Retreat from Nashville, 1864 (2011). A resident of Bishopville, South Carolina, he is currently writing a book about soldiers from that state who fought at Antietam.

Notes

1. Arthur Peronneau Ford, Life in the Confederate Army: Being Personal Experiences of a Private Soldier in the Confederate Army (New York, 1905), 54.

2. William B. Taliaferro, “General Taliaferro’s Report of the Battle of Averysboro, North Carolina,” Southern Historical Society Papers vol. 7 (1879): 31 (hereafter cited as SHSP).

3. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series I, vol. 47, part 2, 821–822 (hereafter cited as OR).

4. Ford, Life in the Confederate Army, 45; Confederate Veteran, vol. 20 (February 1912): 84.

5. Taliaferro, “Report,” 32; OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 2, 861, 867.

6. Charlotte Rhett, “Frank H. Harleston: A Hero of Fort Sumter,” SHSP vol. 10 (1882): 316.

7. Henry W. Slocum, “Sherman’s March from Savannah to Bentonville,” in Clarence C. Buel and Robert U. Johnson, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), 4: 691 (hereafter BL); William T. Sherman, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected and Edited from His Personal Memoirs (New York, 1962), 449.

8. Sherman, Sherman’s Civil War, 449.

9. OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 2, 861; Taliaferro, “Report,” 32.

10. Ford, Life in the Confederate Army, 51.

11. Daniel Oakey, “Marching Through Georgia and the Carolinas,” BL, vol. 4, 677–679.

12. Ibid.

13. OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 2, 585-586, 789, 801, 907; Taliaferro, “Report,” 32–33.

14. OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 2, 585-586, 789, 801, 907.

15. OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 1, 784, 797, 799.

16. Taliaferro, “Report,” 32–33; Oakey, “Marching Through Georgia and the Carolinas,” 679.

17. OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 1, 623, 611, Series I, vol. 47, part 2, 1402.

18. OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 1, 889–890; Taliaferro, “Report,” 33.

19. Taliaferro, “Report,” 33.

20. OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 1, 484.

21. Janie Smith, to Janie Robeson, April 12, 1865, excerpt courtesy of Averasboro Battlefield Commission.

22. Taliaferro, “Report,” 33; Ford, Life in the Confederate Army, 52–53.

23. OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 1, 833–834, vol. 53, 55, Series I, vol. 47, part 2, 1409; Confederate Veteran, vol. 17 (July 1895): 219; Graham Daves, “The Battle of Averysboro,” SHSP vol. 7 (1879): 125–126; Ford, Life in the Confederate Army, 52–53.

24. OR, Series I, vol. 47, part 2, 1411, 1406.

25. Sherman, Sherman’s Civil War, 449–450; Taliaferro, “Report,” 33.

26. Slocum, BL, 691.