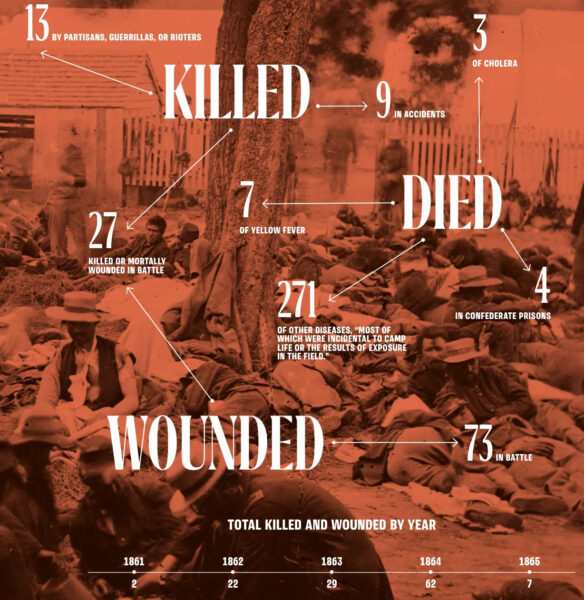

In August 3, 1864, Admiral David G. Farragut, commander of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, was aboard the steamer USS Hartford preparing to take his fleet of warships on a perilous run into Mobile Bay—past Confederate land batteries and lurking underwater mines. His goal was to close the last significant Rebel port on the Gulf of Mexico east of the Mississippi River and complete the Federal blockade of the region. Success could buoy the Union cause and add fuel to President Abraham Lincoln’s reelection bid. Amid these concerns, Farragut took to writing his Navy Department superiors, forwarding two letters and several photographs that he had just received. Sent by recently exchanged army officers, the missives detailed the sufferings endured by Union prisoners of war at Camp Ford and Camp Groce in east Texas. Although a military cartel had recently agreed to exchange 2,500 Federal captives, there were no naval personnel among them.1

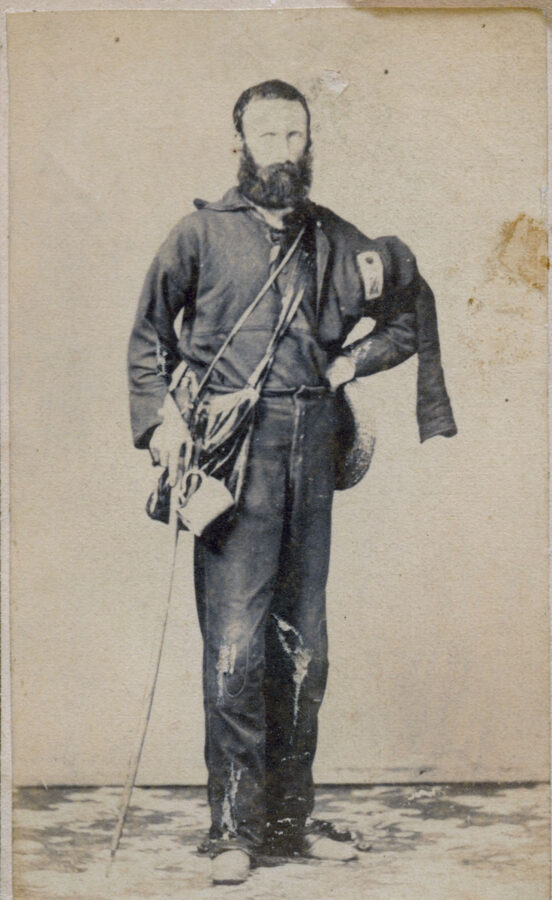

Kevin Canberg Collection

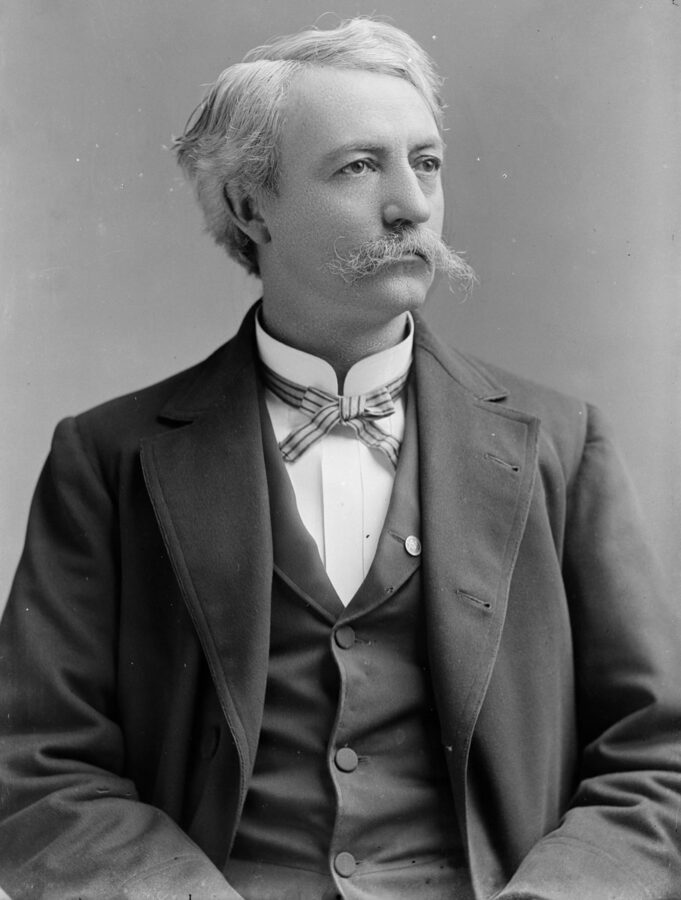

Kevin Canberg CollectionColonel Charles C. Nott (shown as he appeared shortly after his release from prison) was among a handful of exchanged POWs to send Admiral David G. Farragut a letter in 1864 that outlined the sufferings of Union soldiers held captive in Texas.

The highest-ranking signatory on the letters was Colonel Charles C. Nott of the 176th “Ironsides” New York Infantry, an influential prewar lawyer and friend of Lincoln. Nott had spent 13 months imprisoned in Texas after his capture at Brashear City in June 1863 and now was especially concerned for the crews of the U.S. warships Clifton, Sachem, Morning Light, and Diana, men with whom he had spent time at both Camp Groce and Camp Ford. Some of the sailors had been confined nearly 18 months with only beef, cornmeal, and salt to eat—anything else had to be purchased at inflated prices forcing men to weave, create something, or carve trinkets to sell to the local populace. Scurvy outbreaks made citric acid badly needed; prisoners could not procure vegetables or sugar to make vinegar. Nott knew from experience that the malady would only increase with the onset of winter.2

Nott wrote that Rebel authorities in Texas could provide neither hospital stores nor soap to prisoners, and that the few axes provided them were too dull to cut firewood. Clothing had not been issued since November 1863, and many of the men had been without “a change of underclothing upward of half a year, a large part are without shoes, numbers are naked from the waist, and some have nothing but their ragged blankets girt about them in the place of trousers. No great city presents scenes of more squalid destitution than they afford.”3 Nott believed that Confederate commanders John B. Magruder and E. Kirby Smith would allow in the needed supplies if Union authorities provided them. He added that Magruder proposed releasing Acting Master John Dillingham of the USS Morning Light, the highest ranking naval officer in captivity, on a six-month temporary parole to plead his crew’s case in person to Union authorities.4

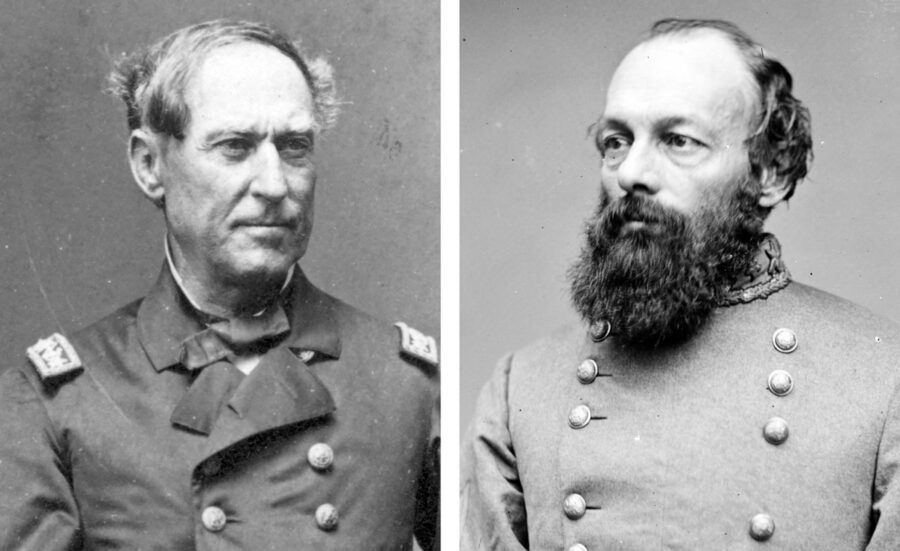

Library of Congress

Library of CongressDavid G. Farragut (left) and E. Kirby Smith

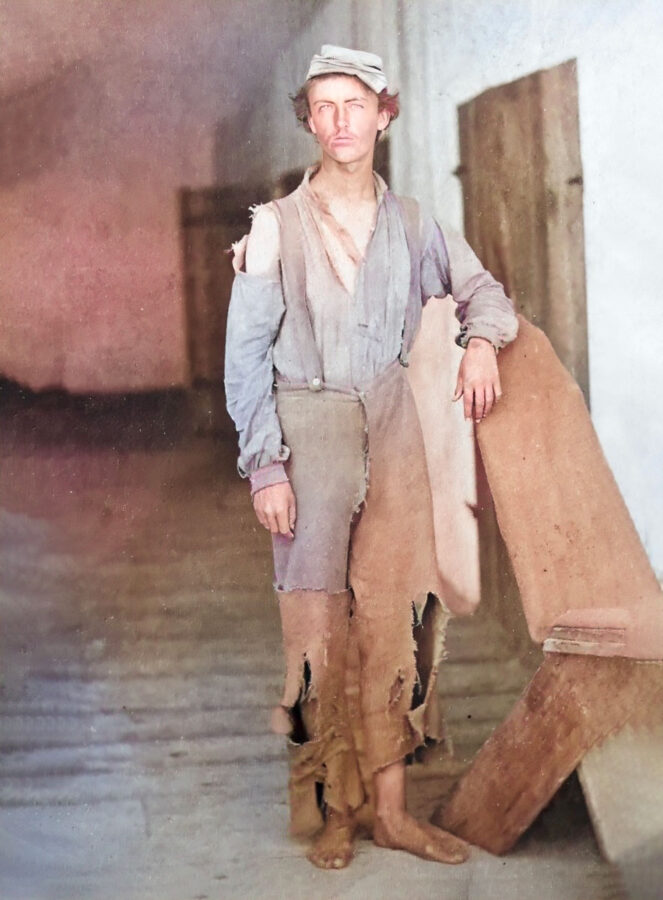

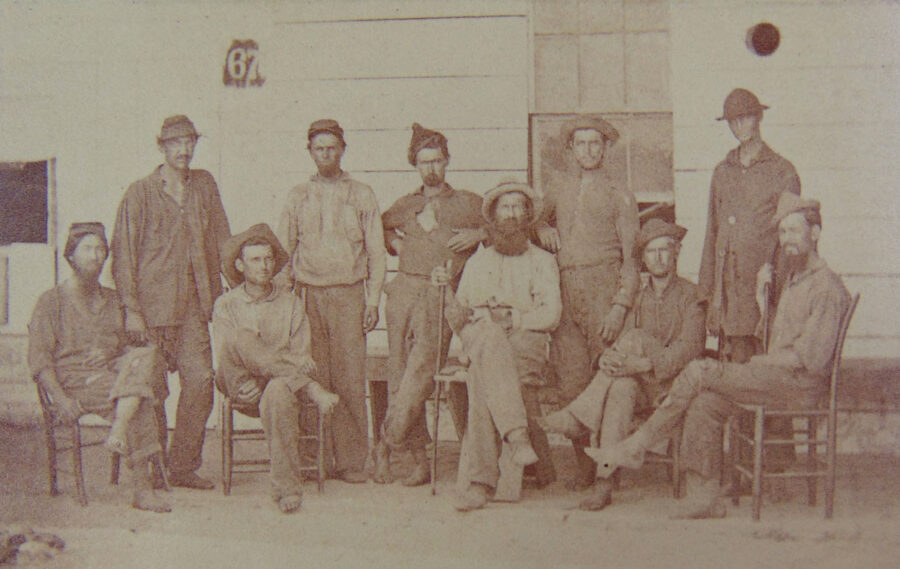

To illustrate his point, Nott enclosed photos of soldiers from the 19th Iowa and 26th Indiana infantry regiments who had been released recently from Texas prison pens. The gaunt and ragged figures were “not exceptional cases,” Nott wrote, but fairly represented the entirety of the camp population. In fact, he wrote, “their appearance being in camp much worse than their photographs represent.” Much dismayed by these reports, Farragut forwarded the images to Washington, asking Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles: “Can not something be done to affect their exchange?”5

Among the images was one of a lone prisoner. The youthful face had clearly seen war’s hardships and his ragged clothing and bare feet spoke of deprivation endured since his capture in September 1863. Who was he?

National Archives (colorized by Patrick Brennan)

National Archives (colorized by Patrick Brennan)James Dungan, a soldier with the 19th Iowa Infantry, as he appeared after his release from a Texas prisoner of war camp.

James Irvine Dungan had been attending college when the war broke out, but on July 22, 1862, he answered President Lincoln’s call for additional volunteers and joined the newly formed 19th Iowa Infantry. Born in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, not far from the Ohio border, Dungan had just turned 18 and stood nearly 6 feet tall with black hair and grey eyes. His father, William H. Dungan, had moved his family and mercantile business to Crawfordsville on the Iowa prairie in the early 1850s. Widowed in 1854, he married again and started a second family while James was educated at a local academy and then enrolled at United Presbyterian College in nearby Washington.6

Dungan was mustered in for three years’ service with the rank of corporal in Company C at Keokuk, Iowa, on August 18, 1862. Like many Midwest units, the 19th Iowa largely comprised farmers, blacksmiths, clerks, and carpenters. Over the next eight months Dungan performed a number of jobs, including as hospital nurse, clerk, and acting sergeant major.7 On September 4, 1862, the 19th left the state for St. Louis, where it joined Brigadier General Francis J. Herron’s division of the Army of the Frontier commanded by Brigadier General John M. Schofield. That autumn it moved to Rolla, then to Springfield, skirmishing with enemy forces in Missouri. In early December a strenuous forced march into northwestern Arkansas by Herron’s division helped secure Union victory at the Battle of Prairie Grove, but at a high cost in casualties, including the death of the 19th’s field commander, Lieutenant Colonel Sam McFarland.8

The Army of the Frontier spent the spring and early summer of 1863 maneuvering in southern Missouri, and in June the 19th Iowa received orders recalling it to St. Louis for transfer to Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s forces besieging Vicksburg. Dungan (who had given up his noncommissioned officer rank) and his comrades were transported downriver to Young’s Point, Louisiana, and crossed the Mississippi River to Warrenton to take up a position on the extreme left of Grant’s lines. The stronghold’s surrender two weeks later freed the regiment for another amphibious expedition, this time up the Yazoo River to seize Yazoo City. That accomplished, the 19th Iowa moved south to camp near Port Hudson, Louisiana.9

While awaiting their next deployment, the Iowans were sent out on several foraging expeditions; in mid-August they once again boarded steamers to be shuttled north of Baton Rouge to establish a new camp at Carrollton, Louisiana. Orders arrived in early September for an action to be staged to divert enemy attention away from a larger Union expedition underway in Bayou Teche. On the same day that most of the 19th Iowa and 94th Illinois, along with 125 horses, boarded the steamboat Sallie Robinson to begin their part in the ordered demonstration, Dungan wrote a letter to Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas requesting an officer’s commission in one of the new African-American regiments recently authorized by the War Department. Major John Bruce, Dungan’s commander, endorsed the application saying Dungan had “proved himself a faithful soldier” and if promoted would make “a faithful & competent officer.” Landing below the mouth of the Red River at Morganza, Louisiana, the diversion’s intended starting point, the military situation did not strike Dungan as promising; Herron’s division “seemed in a half disorganized state, part of the troops remaining on the boats and many straggling out on shore whenever a convenient shade could be found.” Dungan also noted that no more than “three picket posts protected a large number of roads, and a spirit of carelessness prevailed.”10

The order that came for Lieutenant Colonel Joseph B. Leake of the 20th Iowa to take a small provisional brigade and launch a reconnaissance probe toward the Atchafalaya River altered Dungan’s life. The brigade’s size, Leake’s unfamiliarity with the area, and foul weather hobbled the movement and a Confederate counterattack resulted in the Battle of Stirling’s Plantation (also known as the Battle of Fordoche Bridge). On September 29, 1863, Confederate horsemen routed Leake’s small cavalry support, ensuring that his infantry faced assault from all sides. When Leake fell wounded, no other officer took command and the Union lines crumbled. Outnumbered, leaderless, and weakened by heat and exhaustion, the Federals surrendered; nearly 500 men were killed, wounded, or captured with only a few escaping.11

Dungan was among the soldiers marched off through rain and mud into captivity. Provided meager rations of beef and corn meal, the prisoners were shifted by stages to Alexandria, Natchitoches, Mansfield, and Shreveport. At Natchitoches, Dungan eluded guards long enough to escape into the countryside, where he enjoyed surprising hospitality from several Unionist families before being recaptured. Arriving in mid-October at Camp Ford in Tyler, Texas, 100 miles west of Shreveport, after hot and dusty marches, Dungan and his fellow captives found their prison to be a loosely fenced hillside pen surrounded by piney woods. With no shelters available, many men burrowed into the earth along with the tarantulas, centipedes, and scorpions, sometimes with fatal results. The men’s only comfort was a spring of abundant clear water. Axes were scarce, forcing the men to fashion rudimentary tools from iron spikes and other items.12

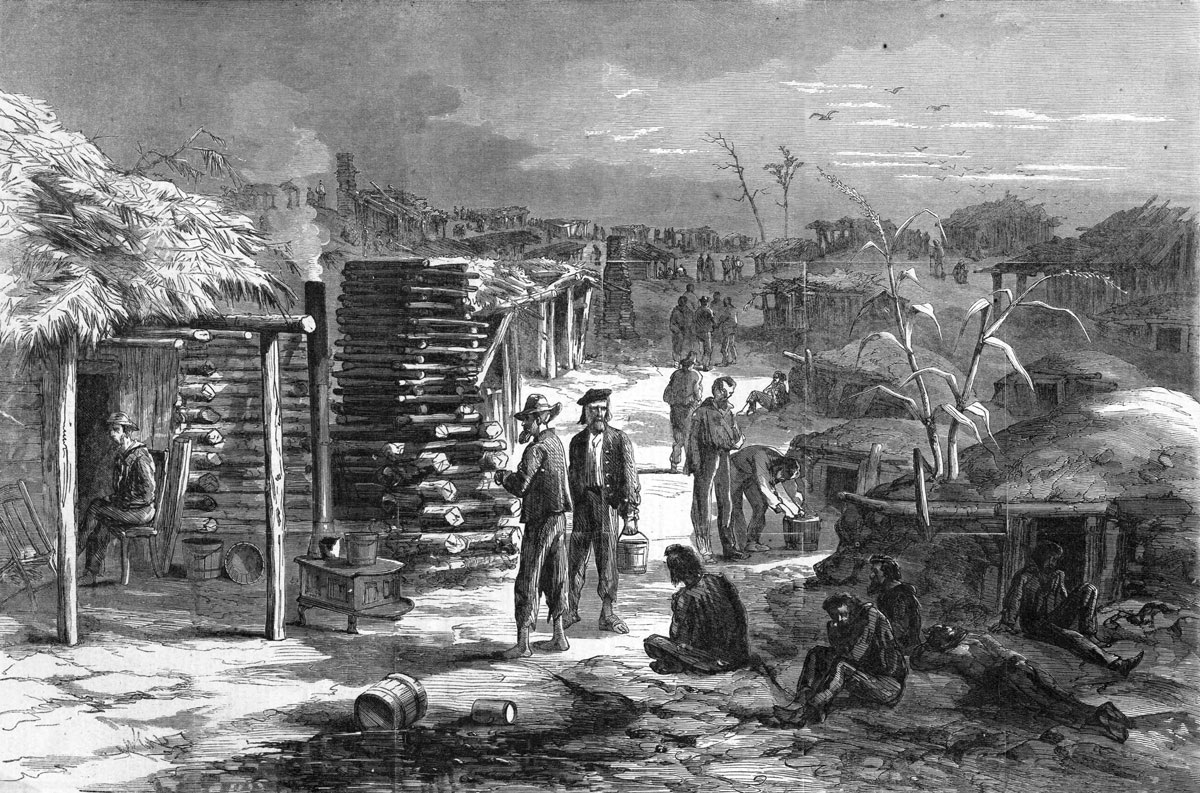

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyAfter his capture in September 1863, James Dungan was sent to Camp Ford (pictured above in an illustration from Harper’s Weekly) in Tyler, Texas, a loosely fenced hillside pen surrounded by piney woods.

Tyler served as a headquarters and manufacturing center for Confederate Trans-Mississippi forces. Camp Ford had originally been an instruction camp for Texas recruits and conscripts, but its purpose changed when the first Union POWs arrived in August 1863. By war’s end, it had become the largest Union prisoner camp west of the Mississippi, encompassing nearly 16 acres and holding more than 4,000 men. The camp at first had no stockade, only a “deadline” enclosing several acres, and a single plank-roof shed with prisoners guarded by local militia. When a new batch of prisoners arrived in mid-October, Dungan among them, the camp faced a security crisis with only 38 guards present.13

Determined to act before security increased, Dungan plotted an escape, but fellow inmate Nott noted the geographic obstacle to the plan: distance. After escaping the guards and the stockade, it was 200 miles south to the Texas coast, 150 miles east to the Red River Valley, and for 500 miles westward lay desolate prairies. Some 300 miles to the north lay Fort Smith on the Arkansas River, just across the border from the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory. The post had recently been occupied by Major General Frederick Steele’s Union forces, making it a haven for refugee slaves, southern loyalists, and others looking to escape the guerrilla warfare raging in the region. That is where Dungan hoped to find freedom.14

On the night of November 8, 1863, Dungan and two companions, Horatio W. Anderson and William McGregor, escaped Camp Ford and headed north. Thus began a series of spine-tingling adventures lasting nearly two months, an account of which Dungan detailed in the regimental history he wrote after the war. Moving by night and concealing themselves by day, the trio avoided the local populace as much as possible, but always found help among the slaves along their route. After numerous hardships and dangers, including being detained by a band of lawless Confederate-associated guerrillas, Dungan and his companions were recaptured on January 2, 1864, having come tantalizingly close to Union lines near Little Rock, Arkansas.15

Marched to Camden, Arkansas, they faced the post’s youthful commander, Colonel Edward E. Portlock Jr., who informed Dungan that he himself had “been abused while in Yankee hands and now I should smell hell.” The prisoners were stripped of combs, pocketknives, blankets, extra clothing, money, and watches. When Dungan refused an order to clean a neglected privy, he was showered with “language that will not bear repetition” and told he would be given a taste of recalcitrant slave-breaking methods. Roughly clapped in figure 8 handcuffs with a rope passed through, he was slung off the ground from a ladder leaned against a wall. After 90 minutes he fainted, was cut down, and beaten with a cane to “make me lively” and “do as much [work] as any two.” Dungan later claimed that Portlock broke four of his lower teeth and three of his upper front teeth; he already bore battle scars on his forehead and leg from glancing bullets.16

National Archives

National ArchivesThis photograph of soldiers recently released from a Confederate prison was among those sent to Admiral David Farragut in the summer of 1864 to alert him to the plight of Union POWs in Texas.

Dungan and other Federal prisoners were made to shell and sack corn and work on Rebel fortifications. Toward the end of January, Dungan was taken to the Shreveport jail, but threats of a spring Union offensive caused all prisoners to be hastily marched to Texas. When Dungan returned to the overcrowded Camp Ford at the end of March, there was a pile of rough coffins stacked at the gate and an added kennel for bloodhounds to track escapees. Conditions had worsened since his escape, with many men in tattered clothing and swarming with lice. When midsummer rumors of exchange proved true, a contingent of nearly 1,000 men endured a difficult march to Shreveport. Floated down the Red River, Dungan and his comrades reached the Mississippi at Red River Landing and were exchanged on July 22. Taken aboard the steamboat Nebraska for the trip to New Orleans, Dungan relished the hardtack and coffee they were provided, noting that “the change was greater than ever before I experienced.”17

Two days later the prisoners arrived on a Sunday in the Crescent City amid pealing church bells, their large number and butternut rags attracting the attention and then the fury of crowds of onlookers who took them to be Confederate prisoners. A newspaper account published the following day, later reprinted across the North, described the scene:

Our citizens were astonished by the apparitions of a regiment, the like of which certainly never marched through the streets of any Christian city. Hatless and shoeless, without shirts and even garments that decency forbids us to name, they were greeted with a murmur of indignation almost universal…. Decency forbids us to describe the utter nudity of these men, officers and soldiers. Many of them had not rags to be ragged with, and as their bare feet pressed the sharp stones, the blood marked their tracks. Animated skeletons marching through the streets of New Orleans.18

It was in that disheveled state that Dungan and groups of other parolees stood before a photographer so that Admiral Farragut and others might see the privations being endured by Union prisoners of war in Texas and work to secure the naval prisoners’ release. Why Dungan was selected to be the subject of a separate photo was not recorded. He and his compatriots were fed and clothed and soon reunited with the portion of the 19th Iowa that had not accompanied the disastrous expedition to Stirling’s Plantation. These men had themselves just returned from monthslong duty as part of Union efforts to land on the Texas coast at Brazos Santiago and occupy Brownsville, until they were withdrawn at the end of July 1864.19

Once again whole, the 19th Iowa shipped out in August headed for Fort Barrancas, guarding the harbor entrance to Pensacola, Florida. Dungan was among the troops pleasantly camped on a white sand beach, though soon enough he was detailed for service as a clerk at district headquarters. Near the end of the year the Iowans were shifted to Fort Gaines, Alabama, and at the end of February 1865 they crossed Mobile Bay to Fort Morgan as reinforcements for Major General Edward Canby’s planned advance on Spanish Fort and Fort Blakely, the holdout city of Mobile’s main defenses. In April, Dungan took part in the brief siege of Spanish Fort, during which he was promoted to sergeant and designated as a color bearer.20

Spanish Fort’s capitulation on April 8 was followed the next day by the capture of Fort Blakeley, which coincided with Robert E. Lee’s surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. With the war over, Dungan’s company returned to Fort Gaines to assist in dismantling Rebel fortifications, the men eagerly awaiting mustering-out. Fresh instructions instead sent them back to Mobile to serve as occupation troops, but on July 10, 1865, the long-awaited order arrived. A joyful trip north soon commenced; Dungan and his regiment first shipped to New Orleans and then upriver, steaming past Morganza and Vicksburg, “taking our last look at them gladly,” as Dungan later noted. They boarded a train at Cairo, Illinois, and rode through the state to Davenport, Iowa, where the regiment was paid off and disbanded on July 31.21

Almost immediately after Dungan returned home, he began working on his History of the Nineteenth Regiment, Iowa Volunteer Infantry, one of the first unit histories written while memories were still fresh and published before the end of the year. In January 1866, Dungan moved to Jackson, Ohio, where he had extended family. There he worked as a newspaper editor, studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1868 before opening a law partnership with Levi Dungan. Irritated that his mail was constantly being confused with that of a cousin Jacob J. Dungan, he thereafter became known by his middle name, Irvine.22 On November 15, 1868, he married Anna Laird and they had three children, Irvine Laird (1869), Nellie Margaret (1871), and Emma Corinne (1876).23

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAfter the war, Dungan (who began going by his middle name, Irvine) married and began a career of public service, which peaked during his term as a U.S. Representative from Ohio in the early 1890s. Dungan is shown above in a photo made during his time in Congress.

Dungan began a remarkably active and diverse career of public service. He became Jackson’s superintendent of schools and county school examiner before entering local Democratic politics. In 1869 he was elected mayor and then served a term in the Ohio Senate, afterward serving as a delegate to the 1880 Democratic National Convention in Cincinnati. In 1890 he was elected to represent Ohio’s 13th Congressional District as a member of the 52nd Congress (1891–1893). When he failed to win reelection in 1892, Dungan remained in Washington, working as a lawyer for the Interior Department until 1895, when he returned to Jackson and resumed his law practice. His final public post was that of city solicitor in 1913.24

As the 20th century began its second decade, infirmities took their toll on Dungan. In his application for a federal veterans’ disability pension, and as a former prisoner of war, he included affidavits from doctors who outlined his numerous ailments, including vertigo, lumbago, partial blindness due to cataracts, and organic heart disease.25 His dizzy spells and numerous falls, in addition to his need for assistance in dressing and undressing, convinced his daughter Emma that he “should be always under the watchful eye of someone.”26 Widowed in 1920 and suffering with declining health, Dungan lived to be 87 and died on December 28, 1931. To honor the veteran from Iowa and former member of Congress, a flag was draped on Dungan’s coffin for services at his surviving daughter’s home. He was interred at Jackson’s Fairmont Cemetery.27

James Irvine Dungan’s Civil War is both unique and ordinary. In the more than a century and a half since war’s end, his words describing the dangers and horrors he endured still have an impact. Yet it is the haunting 1864 photograph that most starkly tells Dungan’s war story. His resolute image and soiled prison rags resonate today as they did with Admiral Farragut. Introducing his unit history, Dungan wrote that it was his intention to detail some of the Civil War “adventures, common to thousands of men, who have often had occasion to choose for their motto … Never say die.”28

David J. Gerleman is a historian, lecturer, and Fulbright Scholar specializing in Abraham Lincoln and the American Civil War era. He has taught at George Mason University since 2002, is a former editor for The Papers of Abraham Lincoln, and resides in Alexandria, Virginia.

Notes

1. David G. Farragut to Gideon Welles, August 3, 1864, Naval Records Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library, 1882-1946, Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Navy, 1798-1921, Correspondence, 1798-1918, Letters Received from Commanding Officers of Squadrons (“Squadron Letters”), 1841-1886, Record Group 45, Entry 45, vol. 196, National Archives, Washington, D.C. (hereafter Squadron Letters/NARA); Brad Clampitt, “Camp Groce, Texas: A Confederate Prison,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 104, no. 3 (2001): 364–384; “Camp Ford,” smithcountyhistoricalsociety.org/camp_ford/history.php (hereafter CF1); “Camp Ford,” texasbeyondhistory.net/ford/, accessed March 1, 2024 (hereafter CF2).

2. Charles C. Nott and others to David G. Farragut, July 30, 1864, Squadron Letters/NARA; Frederick Crocker to David G. Farragut, June 7, 1864, U.S. War Department, Official Records of the War of the Rebellion (Washington, D.C., 1899), Series II, Vol. VII, 210 (hereafter OR; all subsequent references to Series II, Vol. VII unless otherwise noted); Charles C. Nott, Sketches in Prison Camps: A Continuation of Sketches of the War (New York, 1865), 41, 170; “The Capture of Brashear City by the Rebels,” The New York Times, August 9, 1863; “Nott, Charles Cooper,” fjc.gov/history/judges/nott-charles-cooper; “Charles C. Nott dies at 88,” The New York Times, March 7, 1916. President Abraham Lincoln appointed Charles Cooper Nott a United States Court of Claims judge on February 21, 1865.

3. Charles C. Nott and others to David G. Farragut, July 30, 1864, Squadron Letters/NARA; Charles C. Nott and others to Edward Canby, June 7, 1864, OR, 208-209; Nott, Sketches in Prison Camps, 170; “176th Regiment,” museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/infantry-2/176th-infantry-regiment.

4. David G. Farragut to Gideon Welles, August 22, 1864; Report of Acting Master John Dillingham to Gideon Welles, July 25, 1864, Annual Reports of the Navy Department, Report of the Secretary of the Navy with appendix, Containing Reports from Officers (Washington, 1864), 497–498; John Dillingham to Henry W. Wessells, November 21, 1864, John Dillingham to Gideon Welles, December 19, 1864, RG 45, M148, U.S. Navy Officers Letters, 1802–1884, Vol. 642; “Unsere Gefangenen in Texas,” Illinois Staats-Zeitung, August 24, 1864; “A Naval Officer Paroled,” The Evansville Daily Journal, August 23, 1864. Part of Dillingham’s mission was to secure his own exchange for that of Confederate naval commander Charles Fowler or report back to captivity in Texas in January 1865. Dillingham lobbied ranking Union officials, pointing out his men had been in Rebel hands longer than any other Union POWs up to that time.

5. Charles C. Nott and others to David G. Farragut, July 30, 1864, David G. Farragut to Gideon Welles, August 3, 1864, Squadron Letters/NARA; Charles C. Nott and others to E. Kirby Smith, June 7, 1864, OR, 208-210.

6. “Dungan, James Irvine,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/D000539; Eighth Census of the United States (1860), Washington, D.C., Washington County, Iowa, 182; “William Holland Dungan,” findagrave.com/memorial/66826870/william_holland_dungan, accessed February 27, 2024; Mrs. Harlan B. Quinton, “Early Denmark and Denmark Academy,” The Annals of Iowa, vol. VII, No. 1 (April 1905): 1-15.

7. General Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, Records of the Record and Pension Office, Carded Military Service Records, Compiled Military Service Record of James Irvine Dungan, Co. C, 19th Iowa Infantry, RG 94, Entry 519, NARA (hereafter Dungan CMSR); Guy E. Logan, Roster and Record of Iowa Soldiers in the War of the Rebellion Together with Historical Sketches of Volunteer Organizations, 1861-1866, Vol. III (Des Moines, 1910), 235.

8. J. Irvine Dungan, History of the Nineteenth Regiment, Iowa Volunteer Infantry (Davenport, 1865), 41-42, 54-55; “Great Battle in the West,” Indiana Messenger, December 17, 1862; “More Glory for Iowa,” Muscatine Weekly Journal, December 12, 1862; James G. Blunt to Samuel R. Curtis, December 20, 1862, Compiled Returns, Army of the Frontier, War Department, OR, Series I, Vol. xxii, pt. 1, 85-86; “Union Iowa Volunteers, 19th Regiment, Iowa Infantry,” nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UIA0019RI; “19th Iowa Regiment, A Journal of Travel” oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81g0tvs/, accessed March 2, 2024.

9. Dungan, History of the Nineteenth Regiment, 75-81; Logan, Roster and Record of Iowa Soldiers in the War of the Rebellion, 235.

10. James Irvine Dungan to Lorenzo Thomas, September 5, 1863, Dungan CMSR; Dungan, History of the Nineteenth Regiment, 82; “From the Lower Mississippi,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, August 28, 1863; “General Thomas’ Mission,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 29, 1863. The town’s name is alternately spelled Morganza and Morganzia.

11. N.J.T. Dana to Charles P. Stone, September 29, 1863, War Department, OR, Series I, Vol. xxvi, pt. 1, 321-325; John Bruce to Nathaniel B. Baker, October 15, 1863, OR, Series I, Vol. xxvi, pt. 1, 325–326; “Expedition to Morganza,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 12, 1863; “Battle of Fordoche,” The Galveston Weekly News, October 28, 1863. “Battle of Bayou Fordoche,” hmdb.org/m.asp?m=94325, accessed February 29, 2024.

12. Dungan, History of the Nineteenth Regiment, 104; Nott, Sketches in Prison Camps, 170.

13. CF1, CF2.

14. Nott, Sketches in Prison Camps, 171.

15. Dungan, History of the Nineteenth Regiment, 143. For Dungan’s full story of his escape, see 124-145.

16. Statement of James Irvine Dungan, June 23, 1865, Dungan CMSR; “Bureau of Pensions Questionnaire,” July 13, 1906, Pension File of James Irvine Dungan, RG 94, Entry 15, NARA; “Field Officers and Staff, 24th Arkansas Infantry Regiment, Confederate States of America,” couchgenweb.com/civilwar/24inff&s.html, accessed March 1, 2024; “Col. E.E. Portlock,” Salem Times Register, April 15, 1887; “Col. Edward Edwards Portlock Jr.,” findagrave.com/memorial/38658191/edward-edwards-portlock.

17. Dungan, History of the Nineteenth Regiment, 105-107; 108-109; 110-111; 144; Charles C. Nott and others to Edward Canby, June 7, 1864, OR, 208-209; Charles C. Dwight to I.G. Szymanski, August 10, 1864, I.G. Szymanski to Charles C. Dwight, November 18, 1864, OR, 573-574; 1138-1139.

18. “Arrival of Prisoners,” La Porte Union, August 10, 1864.

19. Dungan, History of the Nineteenth Regiment, 115-118.

20. Dungan CMSR.

21. Dungan, History of the Nineteenth Regiment, 161-163; 165; 168; 171; Dungan CMSR; Pension File of James Irvine Dungan; “19th Iowa,” oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81g0tvs/. At its largest, the regiment consisted of 1,132 men, 92 of whom died in battle and 100 from disease, totaling 192 fatalities during the war.

22. James Irvine Dungan to Commissioner of Pensions, February 20, 1907, Pension File of James Irvine Dungan; “Trial of Anna C. Tilton,” The Jackson Standard, March 19, 1874; “Jackson County Literary Society,” The Jackson Standard, August 5, 1880.

23. “Death Claims Irvine Dungan,” The Portsmouth Times, December 29, 1931; Pension File of James Irvine Dungan; “James Irvine Dungan,” findagrave.com/memorial/13072449/james-irvine-dungan, accessed February 29, 2024 (hereafter JIDFIND).

24. “Dungan, James Irvine,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/D000539, accessed February 3, 2024 (hereafter Dungan Bio); Emma Dungan Schellenger to E.W. Morgan, March 18, 1932, Pension File of James Irvine Dungan; “Ohio Briefs,” The Sandusky Star-Journal, December 29. 1931.

25. Medical Exam, May 6, 1925, and May 27, 1931, Pension File of James Irvine Dungan.

26. Pension File of James Irvine Dungan.

27. “Ex-Solon Dies,” The Athens Messenger, December 29, 1931; “Irvine Dungan,” The Portsmouth Times, December 30, 1931; Dungan Bio; JIDFIND; Emma Dungan Schellenger to E.W. Morgan, March 18, 1932, Pension File of James Irvine Dungan. His final burial expenses totaled $474.

28. Dungan, History of the Nineteenth Regiment, v.

Related topics: prisons and prisoners