LEWIS JOHNSON’S PATH to command was typical of an officer in the Civil War. He was 20 when he enlisted in the 10th Indiana Infantry in 1861, and within months he held a lieutenant’s commission. For the next year, the 10th Indiana saw action in western Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi, and by mid-1862 Johnson had risen to the rank of captain. After the Confederate defeat at Chattanooga in late 1863, Johnson found himself with little chance for advancement beyond company command. Then opportunity presented itself when the U.S. War Department’s Bureau of Colored Troops began raising United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments from the Tennessee River Valley region.

Ambitious Union volunteers could obtain an officer’s commission beginning in 1863 by applying for company officer positions in one of the newly recruited “colored” regiments, as they were labeled in the parlance of the time. These black regiments were to be staffed by white officers, most of whom would be drawn from the ranks of experienced enlisted men and junior officers like Johnson. Contrary to popular mythology, white soldiers who applied to serve as officers in black regiments were only rarely motivated by a spirit of abolition or justice or equality. Many were driven solely by ambition. As historian William A. Dobak observes, “contemporary public opinion about race guaranteed that opportunists would far outnumber abolitionists in the [USCT] officer corps as a whole.”1

USAHEC

USAHECLewis Johnson

Officers in USCT regiments, whether opportunists, abolitionists, or something in between, could occasionally expect to feel a certain disdain from their fellow whites to accompany the honor of a commission. “You have doubtless heard that the Governor is enlisting negroes and forming negro regiments,” wrote one member of the 25th Wisconsin Infantry. “They are officered by whites and there are a lot of candidates for positions in all the white regiments. Some 25 have applied for positions from our regiment. There is a lot of joking on the side about the fellows that want to officer the nigger regiments.”2 Such stigma aside, a USCT commission appealed to men like Johnson, who saw it as a chance to rise in the ranks. In September 1864, Johnson was promoted to colonel and put in command of the 44th United States Colored Infantry. It was while leading the 44th that he confronted one of the most painful decisions any wartime commander of troops might face: deciding their fate.

By October, the strategically vital city of Atlanta had fallen to Union forces under Major General William T. Sherman, and the new commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, General John Bell Hood, was desperate to turn the tide in Georgia. Hood’s goal was twofold: to frustrate or defeat Sherman outside the city, and to try to restore lost Confederate territory in Georgia and Tennessee. He knew Sherman had all the logistical advantages, with more men and supplies, and so he decided on an indirect and disruptive operation rather than a direct confrontation. Hood saw Sherman’s lifeline, the Western & Atlantic Railroad from Chattanooga to Atlanta, as a vulnerable target, and hoped that by attacking the Union army’s supply lines he could force Sherman to abandon Atlanta. He threatened the stubborn Federal garrison at Resaca. And rather than fight it out, instead Hood decided to attack the railroad, destroying track all the way north to Dalton.

When the Confederates began arriving at Dalton, they soon encountered the 44th USCT garrisoning the town. Colonel Johnson’s men had arrived a few weeks earlier and begun fortifying the position, and only a few days before Hood’s arrival had encountered a strong force of Confederate cavalry. The horsemen demanded the garrison’s surrender and Johnson flatly refused; the cavalry withdrew. With reason to be uneasy, Johnson sent for more ammunition and reinforcements, but received neither. On October 12, the Confederates returned in much greater strength.3 Hood himself demanded the regiment’s surrender, and warned, “If this place is carried by assault, no prisoners will be taken.”4 Johnson’s reconnaissance indicated Hood could storm Dalton at will; two Confederate corps were already preparing for action, and a third was reported in the vicinity. Representatives from both sides quickly conferred under a flag of truce; even as they did this, the Confederates began deploying artillery on high ground overlooking the 44th’s fort and easily in Johnson’s sight.

The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

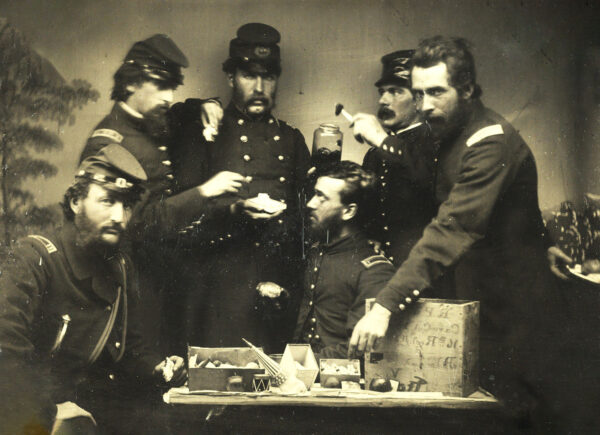

The Huntington Library, San Marino, CaliforniaThis image from 1864 shows the men of an unidentified USCT regiment at their camp at Chattanooga, Tennessee. The white officers and Black soldiers in such Civil War units formed an important partnership, though it was fraught with decisions and dilemmas unlike those in white units.

By afternoon, Hood impatiently summoned Johnson to his headquarters. In a tense exchange, the general ordered Johnson to “decide at once; that I already had occupied too much of his time,” and, as Johnson further reported, “when I protested against the barbarous measures which he threatened … he said that he could not restrain his men, and would not if he could; that I could choose between surrender and death.”5

Johnson understood immediately the position Hood had placed him in. Ordinarily, Union troops who surrendered to Confederates could expect to be treated as prisoners of war; hardly a gentle fate, but much different from what awaited black troops in blue uniforms. Johnson was desperately worried about the lives of his men and asked Hood whether his troops, if they surrendered, would be treated as prisoners of war or slaves. “I was told by General Hood that he would return all slaves belonging to persons in the Confederacy to their masters,” Johnson reported, “and when I protested against this and told him that the United States Government would retaliate, and that I surrendered the men as soldiers, he said I might surrender them as whatever I pleased….” Though fearing the massacre of his men, Johnson made the wrenching decision to surrender.6

Ordering his troops to stack arms and submit to inspection, Johnson watched as the Confederates separated his officers from his soldiers. He was informed that whites would be paroled and exchanged, while blacks would be examined by slaveholders in the Army of Tennessee and, if found to be former slaves, returned to bondage immediately.7 The Confederates began heaping abuse on both the officers and the enlisted men, stealing their shoes and mocking them without mercy. Black prisoners were sent “down to the railroad and made … [to] tear up the track for a distance of nearly two miles. One of my soldiers,” reported Johnson, “who refused to injure the track, was shot on the spot, as were also five others shortly after the surrender, who, having been sick, were unable to keep up with the rest on the march.” Others were again enslaved. “After arriving in the vicinity of Villanow a number of my soldiers were returned to their former masters. This I know was done, because I saw it done in a number of instances myself.”8

After the surrender, all the officers of the 44th USCT requested to remain with the enlisted men rather than go north for parole, but Hood refused them. “As no guards were placed between officers and men that night,” Johnson wrote, “and we expected to be separated from them on the next day, they were instructed how to proceed to make their escape.”9 Even then, the danger was not over for the men of the 44th. Over the next days, “several times on the march [Confederate] soldiers made a rush upon the guards to massacre the black soldiers and their officers. Mississippians did this principally … and were often encouraged in these outrages by officers of high rank,” Johnson reported. “I saw a lieutenant colonel who endeavored to infuriate a mob, and we were only saved from massacre by our guards’ greatest efforts.”10

Johnson and his officers returned to Chattanooga as parolees, and over the next weeks a number of his men, having escaped captivity, joined him there. By November enough soldiers had returned to reconstitute the 44th USCT, and in December Johnson led the regiment into action at the climactic Battle of Nashville.

Johnson’s story illustrates a central truth about the complexity and difficulty of the burden of command. White officers and black soldiers formed an incredibly important partnership during the American Civil War, but that partnership could be fraught with decisions and dilemmas unlike those faced by white units. Leaders in war are sometimes faced with nearly impossible decisions that offer no good outcomes obvious at the time. Johnson chose surrender rather than execution for his men, reasoning that their lives were too valuable to squander, even if it meant separation, a return to slavery, and possible professional disgrace. He remained in the U.S. Army after the Civil War, serving as an officer in the Buffalo Soldiers and retiring after a long military career. For the survivors in the 44th USCT, their story also ended in victory, as part of the western theater’s final great battle at Nashville and the ultimate defeat of the Confederate army that only months before had given them no quarter.

Andrew S. Bledsoe is associate professor of history at Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee. He is the author of Citizen-Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 2015); co-editor, with Andrew F. Lang, of Upon the Field of Battle: Essays on the Military History of America’s Civil War (LSU Press, 2019); and author of the recently released Decisions at Franklin: The Nineteen Critical Decisions That Defined the Battle (University of Tennessee Press).

Notes

1. William A. Dobak, Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862–1867 (Washington, D.C., 2011), 15.

2. Chauncey H. Cooke to Dear Mother, April 10, 1863, in Chauncey H. Cooke, A Badger Boy in Blue: The Civil War Letters of Chauncey H. Cooke, ed. by William H. Mulligan Jr. (Detroit, 2007), 46.

3. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series I, vol. 39, part 3, 39, 31, 57, 784.

4. Ibid., 718.

5. Ibid., 719.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid., 719–720.

8. Ibid., 721.

9. Ibid., 723.

10. Ibid., 720–721.

Related topics: African Americans