Library of Congress

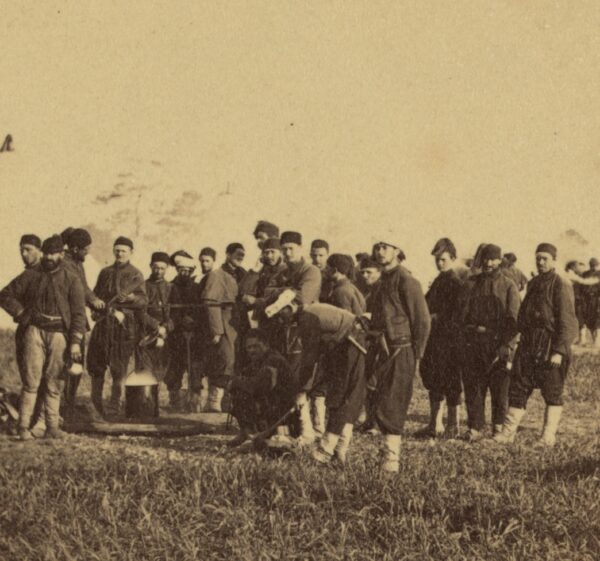

Library of CongressA group of soldiers from the 5th New York Infantry (Duryea’s Zouaves) in camp in 1861.

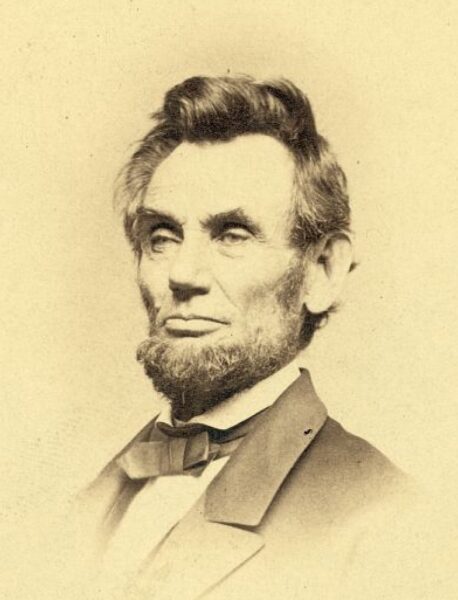

In the wake of the decisive Union defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg, on December 13, 1862, one of the combatants, Alfred Davenport—a sergeant in the 5th New York Infantry (also known as Duryea’s Zouaves)—wrote about his experiences in a detailed letter to his parents. Davenport, who at age 24 had enlisted in the 5th New York on April 25, 1861, would continue to serve with the regiment until mustering out with his company on May 13, 1863, in New York City. His detailed letter about his experiences at Fredericksburg is produced below in full.

Battle of Frederick City.

Camp Falmouth, Dec. 17th, 1862.

It has been an awful time with us for the last week. On the 10th, it was rumored through the camp that the army was to make a grand advance against the enemy, and in the evening it was a certainty.

Accordingly, at half-past two, on the morning of the 11th December, we were aroused by the sound of the bugle ringing out the reveille in the clear cold air. We turned out and immediately commenced our slight preparations for the march. We formed in line, and took the road, already blocked up as far as the eye could reach with moving troops. The sound of a heavy gun in the distance told us that the great ball had opened. From that time the roar of artillery was incessant. After marching about three miles, our division was turned into a wood to await further orders. We were finally marched from the wood to a spot just behind some earthworks on high ground, near the banks of the Rappahannock, from which we could distinctly see the ill-fated city of Fredericksburg, about two miles to the left of us, on the other side of the river, and our batteries playing on to the opposite bank.

Our forces were all day trying to lay the pontoon bridge across the river, but were prevented by the enemy’s sharpshooters, who were posted in the houses along the shore of the city. This obliged us to turn our guns upon the town and shell the place. Soon the city was on fire in several places and continued to burn all night; it was a splendid sight after dark to see the flames burst forth. We could plainly see the enemy’s works on the heights above the town, but they scarcely deigned to reply to our fire; it looked to me ominous. I thought they intended to wait until we crossed into the city, and then pay us off.

The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

The Huntington Library, San Marino, CaliforniaIn this painting by Thure de Thulstrup, Union soldiers attempt to build a pontoon bridge under fire from Confederates positioned in Fredericksburg.

On the 13th our troops have all crossed, with the exception of one division, which is held as a reserve, generally composed of “regulars”—our regiment is considered the same in point of steadiness and discipline. We had, however, besides in our brigade the 140th and 146th New York Volunteers, new men, never having smelt gunpowder before; but they were composed of a hardy set of men from the northern and western part of our State. Soon we were ordered to fall in, and marched towards the river. As we approached the bridge, there were signs of what was going on; pale-looking men limping along to the rear, and here and there a surgeon and his assistant with implements for use, with the wounded and dead lying about them; terrified looking soldiers skulking behind trees, where they thought themselves safe from flying shell.

We crossed the bridge and hurried through a business street, where whole blocks of houses were destroyed by fire, and desolation and destruction was everywhere visible. We turned into a side street, where the houses were all large—the residences of the wealthy inhabitants. The din of battle was terrifying, and from what we could find out the result was uncertain. We came to the end of the street which turned off into the country. It was now dark, and the “regulars” went into it “hot and heavy.” We could have been in instead of them; but they were marching ahead of us, and there was not a moment to spare, and so they were filed off into the fight on a double-quick.

We were turned into a garden. The soil had recently been dug up, was wet and muddy; we were tired out, but there we had to stay, being the next in turn for the trying ordeal. We pulled down a fence, on which we could keep part of our bodies from the mud. The bullets whizzed over our heads from the firing just in front of us. Some of the boys were wounded. I curled up in a heap to keep myself warm, and to keep on the board—my share consisting of a space two and a half feet long, and one and a half broad. I could not sleep; and few there were who closed their eyes that night. As I lay I thought of the morrow—how many of us would live to come out—of home, and of eternity. But worse than all were the cries of the wounded lying between the lines without any one to help them; I could distinctly hear them cry for “water,” and sometimes a chorus of wails and shrieks sent up on the midnight air, telling of human agony beyond the power of endurance! Thus the night wore through, and at daylight we were ordered to fall in. We had no sooner got up than the enemy opened on the “regulars” in front of us from their rifle-pits. The bullets flew around us thick, and began to thin our ranks. Our long line of fire told us where they were, for it was yet quite dark.

We were now hurried off, and went up the same street we came down, about a square, and closed up en masse to cover a body of men from observation, and into a garden with a dwelling in front of us, which somewhat screened us. We had not been here long before some of our men strayed off, and into the adjacent houses, and soon, jars of pickles, preserves, sugar, and all sorts of good things made their appearance; also handsome books, pocket-books of private papers, letters, silk dresses, and every imaginable article of use or luxury, were brought out, and wantonly destroyed by the thoughtless ones. It was ludicrous to see the boys come along with large doll-babies and children’s toys: some of them with wigs on and white beavers, and women’s bonnets and shawls on—but it made one sad to think how comfortable and happy the homes must have been in times of peace, now turned into desolation! It is surely no wonder that it is difficult to conquer such people, when they leave every thing, the houses and homes they were born and brought up in, and, perhaps, their parents before them, rather than surrender them willingly to us. In the afternoon we were marched down the street further, and turned into the yard in the rear of a large brick residence, one of a row, with piazzas, gas-fixtures, and water-pipes, which the rebels had shut off. The kitchen, a small brick house, was connected with the- main building by a covered piazza. Back of it again were rows of neat huts for the colored servants: every thing was “in style.” A bell hung out at the back of the house to waken the “people” in the morning.

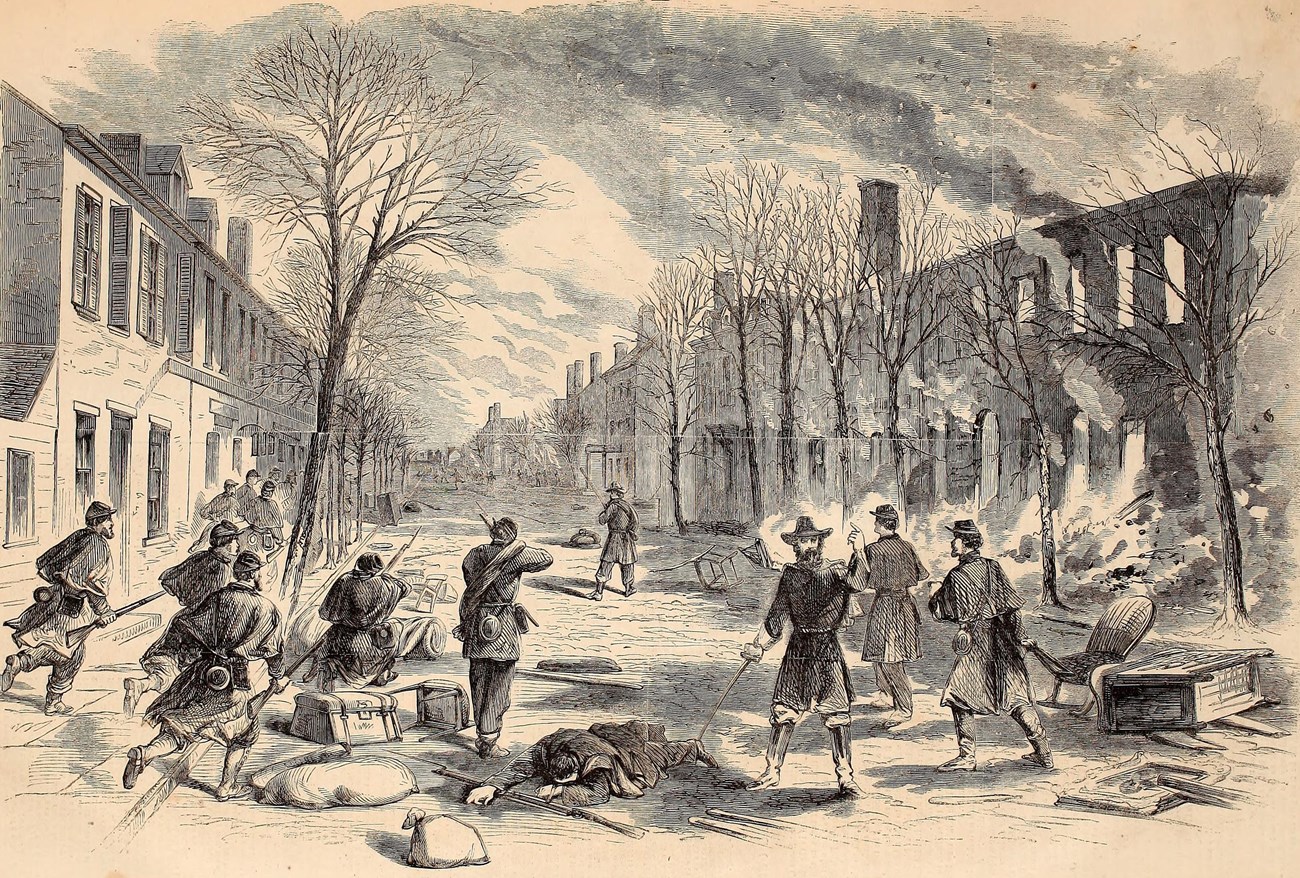

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyUnion soldiers fight through the streets of Fredericksburg on December 11, 1862.

We built a fire in the great stove, and there was the busiest crowd of cooks that ever were seen before! Plenty of flour was to be had in the house (all of them were well stored with provisions), and every man had a soup tureen, or some piece of crockery-ware, mixing flour and water to make slap-jacks.

The house was superbly furnished with every article that wealth could purchase or luxury suggest, and we were in need of nothing that could aid our culinary arrangements. We found splendid hams, preserved trout, farina, &c, and we lived high. The officers had feather-beds at night brought out in the yard to sleep on. We stayed there two days and a night, still under suspense, yet covered by the houses. The regulars could not get off the position assigned them the first night; they had to lay close to the ground, not daring to lift their heads, completely at the mercy of the rebels, who, in their covered rifle-pits, picked them off whenever they moved. They had no water, and suffered terribly. At night, when they crept away, they left ninety-seven of their number lying dead. This was the place we escaped from by a mere chance: our loss there would have been severe, as our red pants and caps make a splendid mark, as the result of the battles we have been in too well show, and the rebels are “down” on Zouaves, and ourselves particularly.

On the third day it began to look serious, as the rebels were advancing their rifle-pits nearer the city every night, and we were hemmed within its limits: the rebel balls were continually flying up the streets of the city: there was no position for our artillery, and, in “the front,” death stared us in the face, and the wide river (Rappahannock) flowed in our rear, between us and safety. If the enemy, from the high bare hills commanding the city, which were crowned by their batteries, should shell the place, in which was massed nearly our entire army, a panic would probably have been created, and the army lost.

In addition to their batteries, they (the rebels) had a stone wall, two or three lines of rifle-pits, and a marsh, all of which we would have to overcome by assault if we gained the victory. General Franklin gained a mile on the left, but was then checked, and could go no further. General Burnside, it was rumored, wanted to storm the position, but was overruled by the other officers in a consultation. He would have lost half of the army! No less than seventeen charges had been made to no purpose: our dead strewed the field. It was sure death to face the batteries, and the wounded were left to die a lingering death between the lines; the rebels shooting any one who ventured to bring them off.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUnion soldiers advance toward the Confederate defensive position outside the city during the Battle of Fredericksburg.

At this time every one’s heart was down in their boots. Officers and men felt alike: the only alternative was a retreat across the river, or to meet sure death in the front. The suspense was worse than death itself, for it was apparent to the most simple that General Burnside had been drawn into a trap; we all knew and felt it. That which had been looked at by our people as so much gasconade in the Richmond papers, was being fulfilled to the letter.

On the third night, we fell in very mysteriously, and were marched towards the front, down a street leading by the outskirts of the city. After some delay, we were finally marched into a large graveyard, with orders to keep very quiet. Here we laid down for two hours: every thing looked very mysterious; I thought that we were going to look for the bones of Washington! It was an aristocratic-looking place. We were then marched into another graveyard nearer the front. Everybody looked at each other and thought that our colonel’s brain had been turned; finally, we were marched directly to the front, where we found some regulars digging rifle-pits for us. We were within three hundred yards of the enemy’s pits; two of our companies, who went further out on picket, could hear the rebels talking. We fell back into the pits just finished. A battery for a few guns was thrown up in our rear. Towards morning we were told to put on knapsacks. The battery quickly moves off with muffled wheels, and it now flashed upon me that the army was retreating across the river, and we were the reserve to cover the retreat, and would be the last to cross over. It now commenced to rain in torrents, and filled the pits. We stood in mud and water up to our knees; the water ran down our backs and chilled us through: it was getting light, and before long our pits must be discovered, and bring upon us the rebels’ guns and sharp-shooters. Officers and men would have given all they possessed to be out of that place. In the horrible moments of suspense, how I inwardly prayed for God to lengthen the morning and keep daylight from us! We could now see the rebel works loom up in the distance, and part of us were ordered to crawl away to the cover of a large storehouse, about two squares off, in the outskirts of the city: here we were soon joined by all the regiment, with the exception of a few men left behind to fire a shot occasionally from the pits, as if they were occupied.

It was now light, and they were popping away at our pits and at us, who were drawn up in a line across the street. We were getting very anxious for General Warren to appear (he had charge of the regiment covering the retreat), to give the signal for moving off.

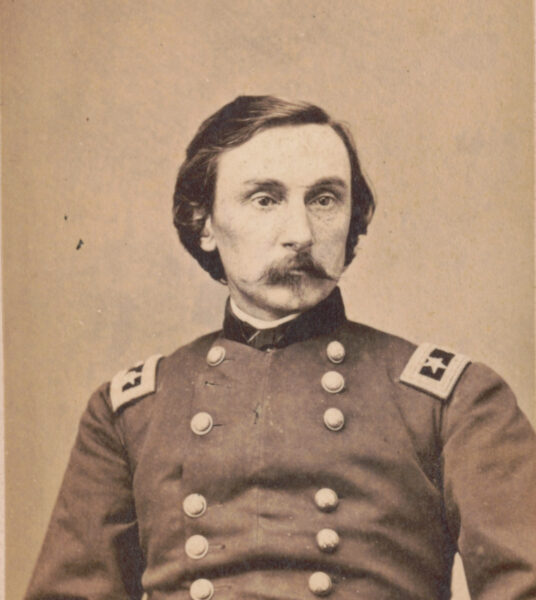

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUnion general Gouverneur K. Warren

We saw rebel officers on horseback going from fort to fort, and knots of men making observations, as if puzzled and not knowing the exact state of affairs. The suspense was now terrible: the officers looked at each other, and would have gladly marched us off themselves, but still General Warren sat on his horse, immovable, about two blocks up the street, and no signal given. At length, down came his aid for the second time, with the welcome order, “Right about face, and march to the river.” Never was order obeyed with more alacrity! Though there was yet danger, the spell was broken; we were moving, and would soon know our fate, and were ready to meet it to the death. The rebels, on the discovery of the evacuation of the pits, would be down on us like a pack of bloodhounds, and we should be obliged to fight our way down through the city, and across the river, and most of us probably sacrificed. We were marching along briskly, when we met Major Cutting, aid to Gen. Sykes, who had been sent to see why we did not appear at the pontoon bridge.

A little further on we came across a brigade of regulars, who had been safe across the river, but were ordered back again, it being feared that we were in trouble. As soon as we got over a little hill in the street, out of sight of the rebels, the order was given “Double-quick,” and we soon reached the pontoons, the brigade of regulars on our heels. As we went up the bank, on the opposite side of the river, we looked back, the rebel batteries had just opened on our rifle-pits, but we had fooled Johnny Reb that time!

We shook hands all around, and bivouacked for the night, thankful for safety; and now here we are, on the same ground we started from seven days ago, having accomplished nothing, our confidence gone, fifteen thousand men less at least! Is it not enough to make us sick of the war, to see how we are experimented with to satisfy popular feeling? I wonder who will be the next man to try experiments with us? By the time they have killed off a lot more of us, they may find a man that can face Lee with success. I still hope on, but I do not much think that I shall live to see you all again; I have had many narrow escapes, and I begin to feel worn out for want of a change of food. I eat very little, and what keeps me alive must be the coffee. I must now bid you all good-by, and may Providence favor our cause, and give to us the victory.

Your affectionate son,

A. Davenport,

Duryea’s Zouaves

Source: Soldiers’ Letters, from Camp, Battlefield and Prison (1865)