John Banks

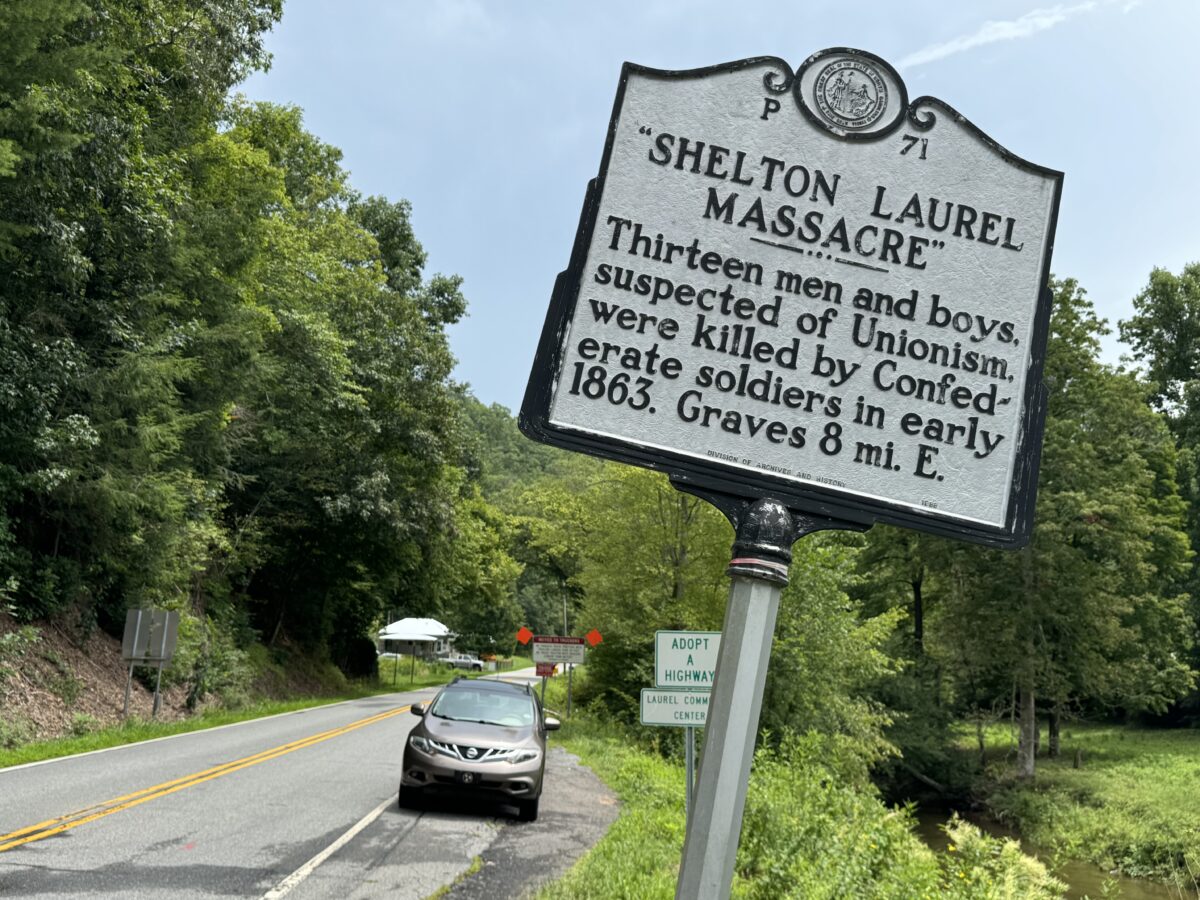

John BanksA historical marker sits about 8 miles from the site of the Shelton Laurel Massacre in western North Carolina.

Deep in the heart of remote Shelton Laurel Valley, in western North Carolina, I pose a question to five women sitting at a table in the community center.

“Can you tell me how I can get to the Civil War cemetery? I don’t want to trespass.”

“Go visit with Paula,” one of them tells me. “She lives in the white house with the garden down the road. Just honk a couple times after you park.” Valley protocol.

And so I travel serpentine Route 212—past the self-serve chicken-, duck-, and quail-egg stand, past Hoot Owl Hollow Road, Devil Fork Gap, and Huckleberry Knob—to arrive at the gravel driveway of the McAllister place, near the cemetery. Bingo, an Aussie shepherd-blue heeler mix, greets me with yaps and growls. No bars on my phone tell me I’m out of luck if a call must be made.

In mid-January 1863, in “Bloody” Madison County here in the southern Appalachians, a wartime atrocity occurred. On a wintry day, Confederate soldiers executed suspected Unionists—men and boys—in a field around the bend from where today stands Old Creek General Store. Afterward, the victims were buried on a ridge not far from the cabin where their killers had held them captive.

After the canine alert, Paula Shelton McAlister, 70, shows up, wondering who the stranger is parked in front of her house in the rain. She has spent nearly her entire life in this sparsely populated place. She can trace her roots back seven generations in the valley, where during the Civil War some supported the Confederacy, others supported the Union, and many didn’t care for either—just wanted to be left alone.

After small talk, McAlister, a former paramedic and admitted eccentric, directs me to the cemetery. She also delivers a warning.

“The folks who live in the house up there behind the fence don’t like strangers,” she says.

“Will they shoot me?”

“I don’t think so.”

Playing it safe, I ask McAlister if she would accompany me.

Nearly giddy with my good fortune, I trek behind McAlister up a well-worn path through the woods, past a ramshackle barn and a crude sign that reads “13 Men and Boys, Graves.”

Some of McAlister’s kin rest in this remote cemetery. In the winter of 1863, Confederates killed several of her distant relatives. “Staunch Unionists,” McAlister calls her ancestors who lived in this pocket of Carolina.

“My daddy wouldn’t let anyone come back here with a Confederate flag,” she tells me. “He’d run them off.”

John Banks

John BanksPaula Shelton McAlister stands beside stones that mark the mass graves of the massacre’s victims.

Along the ridge, McAlister points out ancient graves that long predate the Civil War. Perhaps as many as 100 souls rest here in the woods. Then we come to two large, rectangular gray-granite stones at the mass grave of the Civil War victims. Bright flowers adorn the markers.

My interest in this unheralded story stems from my visit in the summer of 2022 to another small Carolina town, Marshall (population about 800), astride the French Broad River with a funky, hippy vibe. Roughly an hour’s drive east from Shelton Laurel Valley—but a world away.

The tragedy, like the fog that often lingers in the valley, is tinged with mystery. What’s indisputable is that early that long ago January, some 50 Unionists—believed to be mostly U.S. soldiers on leave—ransacked Marshall and raided its salt storage. That expensive and vital commodity was used by the valley population for, among other things, curing meat.

“They thought they had reason to believe that the portion of salt which was due them had been unjustly held,” a contemporaneous North Carolina newspaper wrote of the raiders, “and so they were determined to go to Marshall … and take the salt by force.”1

The Unionists targeted Confederate colonel Lawrence Allen’s house while he was away, and threatened his wife, who was there caring for their three sick children. (The Allens’ two-story house—privately owned today—suffered severe damage along with the rest of Marshall from Hurricane Helene in September 2024.)

Eager to find the raiders, Lieutenant Colonel James Keith of the 64th North Carolina Infantry rode into the valley with his soldiers, who spread terror in their wake. A period newspaper reported Keith’s men tortured two elderly women and mistreated others.

“One woman, who had an infant five or six weeks old, was tied in the snow to a tree, her child placed in the doorway in her sight,” a newspaper reported, “and she was informed if she did not tell about the seizure of the salt, both herself and the child would be allowed to perish.”2

John Banks

John BanksPaula Shelton McAlister at the remains of the cabin where the Shelton Laurel victims were held.

Eventually, Keith’s soldiers rounded up 15 men and boys and put them in a cabin. Two escaped. Had any of them been among the Marshall marauders? Who knows?

The next morning, in a clearing near a stream, executions were carried out. “If you are going to murder us,” one of the victims supposedly said, “give us at least time to pray.”3

The Confederates killed 13 captives, ranging in age from a boy of 12 or 13 to a man of about 60. “Doomed patriots,” a newspaper called them. Hogs reportedly rooted up their mass grave before the victims’ families arrived on the scene.4

Predictably, Unionists denounced the massacre. But the killings also gave at least one Confederate sympathizer reason for concern.

“These men had committed a great wrong against society,” read an account in a North Carolina newspaper. “It may be that death by the law should have been their portion; but the law was not allowed to speak. Its justice was not even invoked. The musket did the work.”5 But none of the Confederate soldiers involved in the massacre, including Keith, the commanding officer, faced any punishment.

At the cemetery, rain dripping from the bill of my ballcap, I scan the names on grave markers: David Shelton, James Shelton, James Metcalf. Then McAlister and I visit the nearby site of the cabin where the captives were held. Only the chimney remains. I stare at the brown stones forming that tall marker against the gloomy-gray backdrop, wondering about the poor souls held there so long ago.

Minutes later, sunlight briefly bursts through the leaden sky.

What a day from history buried in bloody little Shelton Laurel Valley.

John Banks is author of A Civil War Road Trip of a Lifetime and two other Civil War books. A longtime journalist (The Dallas Morning News, ESPN, The History Channel), he is secretary-treasurer of The Center for Civil War Photography. He lives in Nashville with his wife, Carol.

Notes

1. Semi-Weekly Standard, Raleigh, NC, March 15, 1863.

2. Memphis Bulletin, July 15, 1863.

3. The New York Times, July 24, 1863.

4. The New York Times, July 24, 1863.

5. Semi-Weekly Standard, Raleigh, NC, March 15, 1863.