On June 8, 1863, Major General J.E.B. Stuart reviewed his cavalry division on the farm of Unionist John Minor Botts in Culpeper County, Virginia. It was a rare, memorable pageant seen few times on the North American continent that featured an inspection of his troopers by General Robert E. Lee. Little did Stuart realize that as General Lee inspected his troops, 9,000 Federal cavalrymen lay just across the Rappahannock River preparing to attack the following morning. Joseph Hooker, suspicious of the large build-up of Confederate cavalry in Culpeper County, ordered his cavalry commander, Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton, to take the entire Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac out and either disperse or destroy them. Pleasonton took three divisions of horsemen, two brigades of horse artillery, and two brigades of selected infantry (numbering 3,000 men), and prepared to pounce on the Confederate cavalry on the morning of June 9, 1863.

Pleasonton formulated an excellent plan for his foray across the river. His senior division commander, 37-year old Brigadier General John Buford, a native Kentuckian who was a member of the West Point Class of 1848 and a career dragoon, would command the right wing of the operation, including his own First Division and a brigade of infantry. Pennsylvanian Brigadier General David M. Gregg would command the left wing, which included the other infantry brigade, Gregg’s Second Division and Colonel Alfred N. Duffíe’s Third Division. In addition, several batteries of Federal horse artillery would accompany the columns, adding firepower to the already potent Union force.

Under Pleasonton’s plan, Buford’s men would cross the Rappahannock at Beverly Ford, while Gregg’s crossed at Kelly’s Ford. Buford would then ride to Brandy Station, where they would rendezvous with Gregg’s Second Division. Duffíe, a deserter from the French Army, commanded a small division that would also cross at Kelly’s Ford, then proceed to the small town of Stevensburg to secure the flank east of Culpeper. Buford and Gregg would then push for Culpeper, where they would fall upon Stuart’s unsuspecting forces and destroy them. In case Confederate infantry appeared, the Federal infantry would support the attacks. Pleasonton had his men pack three days’ rations because he intended to chase the routed Confederates. Careful timing was required to pull off the attack as planned.

Buford’s veteran division began crossing the Rappahannock at Beverly’s Ford about 5 a.m. on June 9. The division advanced in columns of four, with Colonel Benjamin F. “Grimes” Davis’ brigade leading the way. Davis, a Mississippi-born West Pointer, was known as a martinet, but he was a fine officer. The blue-clad horsemen emerged from the early morning mists to find pickets of Captain Bruce Gibson’s company of the 6th Virginia Cavalry of Brigadier General William E. “Grumble” Jones’ brigade just on the other side of the river. Gibson’s pickets made enough of a stand to allow time for word of the advance of a large Union force to reach Jones, who quickly got his troopers into the saddle and on the move to meet the threat. Davis, far in advance of his brigade, was killed instantly during an encounter with an officer of the 12th Virginia Cavalry, and his leaderless brigade fell back. Jones deployed his dismounted troopers to defend most of the Confederate horse artillery, posted on a ridge line above Beverly’s Ford near St. James Church.

Learning that Davis had been killed, Buford splashed across the river and ordered five companies of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry to charge the artillery. The Pennsylvanians dashed at the guns, losing their commanding officer, Major Robert Morris Jr., who had his horse shot out from under him midway across the wide field. The Keystone Staters reached the barrels of the guns before being repulsed. By this time, troopers of Brigadier General Wade Hampton’s fine brigade of southern cavalry had arrived to reinforce Jones. The battle devolved into a standoff, as Buford’s men made numerous unsuccessful dismounted attacks against a stone wall held in force by troopers of Brigaider General William H. F. “Rooney” Lee’s brigade. The 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, this time supported by troopers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry, made another determined charge at Lee’s position along the stone wall, again taking heavy losses. Buford and his troopers fought alone for nearly six long hours that morning.

In the meantime, David Gregg’s Second Division made its way across the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford and finally headed toward Brandy Station. The lead elements of Gregg’s column came within view of the high ground at Fleetwood Hill and saw that the area was largely undefended, but for the tent fly of Jeb Stuart’s headquarters. One of Stuart’s staff officers spotted the Federal advance, grabbed a single cannon, and sent back to get more ammunition. The lone gun belched fire upon the advancing Federals, who slowed to deploy into line of battle. Stuart, now aware of his critical situation, called for Jones’ and Hampton’s brigades, which galloped several miles from the vicinity of St. James Church to meet the Federals as they advanced on Fleetwood Hill.

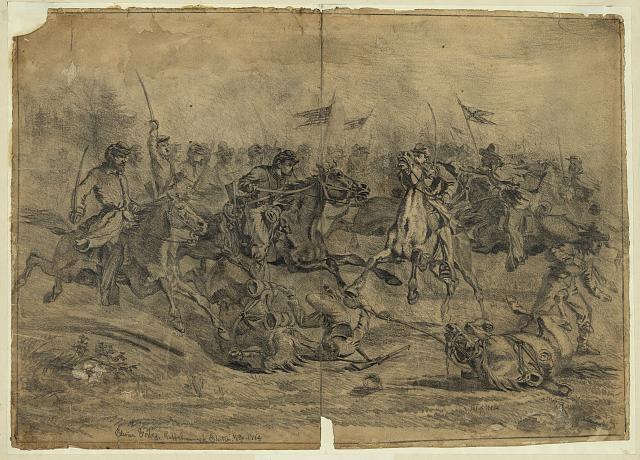

There, in the fields around Fleetwood Hill, played out one of the great romantic dramas of the American Civil War. For hours, mounted charges and countercharges took place, as four full brigades clashed in mounted, hand-to-hand combat. Federal troopers nearly seized Fleetwood Hill and Stuart’s headquarters before finally being driven off.

The focus of the fighting then shifted back to Buford’s troopers. After driving Rooney Lee’s men from the stone wall, Buford sent his Reserve Brigade, consisting of the U.S. Regular cavalry and the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, up Yew Ridge, the northern extension of Fleetwood Hill. The Yankee horsemen gained the crest of the hill before again slamming into Rooney Lee’s men, and another melee of hand-to-hand fighting broke out. Rooney Lee fenced with Captain Wesley Merritt, the commander of the 2nd U. S. Cavalry, and suffered a serious saber wound. Lee’s troopers slowly drove Buford’s men back.

By now, it was nearly 5 p.m., and Pleasonton had seen enough. He ordered his men to withdraw, and they did, slowly and in an orderly fashion, fighting as they fell back. Stuart was perfectly happy to let them go. Both sides suffered significant casualties in a battle that had lasted 13 long hours. The Yankee troopers had given as well as they had gotten, and if the Confederates needed proof that the tide had turned, Brandy Station amply provided the evidence. At the end of the day, Stuart’s troopers held the field. They had prevented Pleasonton’s men from achieving any of their objectives, and they had survived the unpleasant surprise delivered by the Federal horsemen. The great Battle of Brandy Station was over.

But the battle for the future of Brandy Station continues to rage. Today, we are engaged in a fight to save Fleetwood Hill, the site of four different major engagements during the Civil War, and also the site of Major General George G. Meade’s headquarters during the winter encampment of 1863-1864. Sixty-one acres of hallowed ground is presently subject to a purchase contract with the Civil War Trust. The purchase price is high: $3.6 million. Please help us to save Fleetwood Hill by clicking here.

Eric J. Wittenberg is an award-winning Civil War historian whose primary focuses are the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps and the Gettysburg Campaign. He is the author of 17 books on the Civil War. Please visit his blog, Rantings of a Civil War Historian, http://www.civilwarcavalry.com.

This article is based on research for the author’s book on the Battle of Brandy Station. For more information, please see The Battle of Brandy Station: North America’s Largest Cavalry Battle (2010), available from the History Press.

Illustration courtesy Library of Congress (loc.gov).