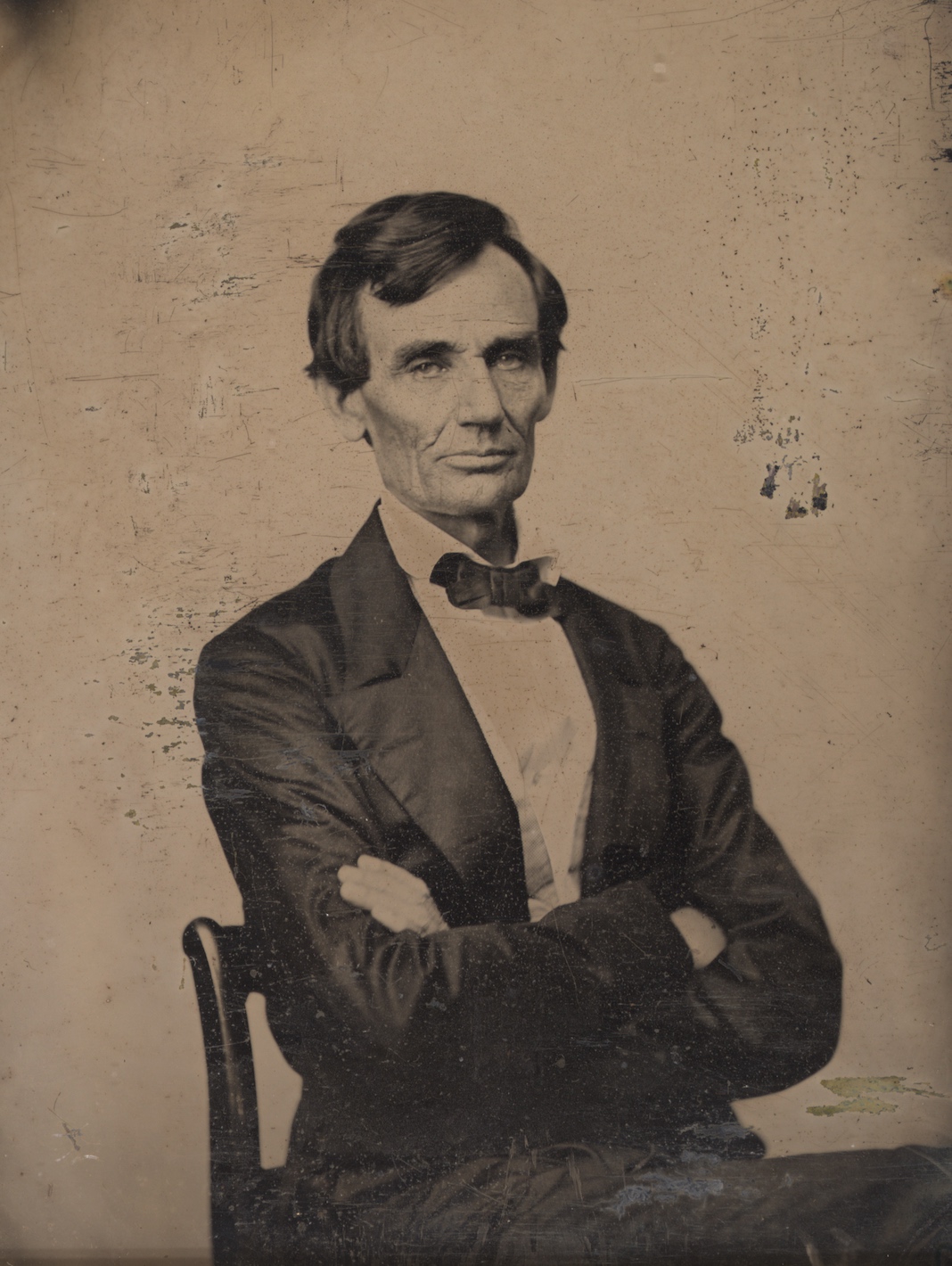

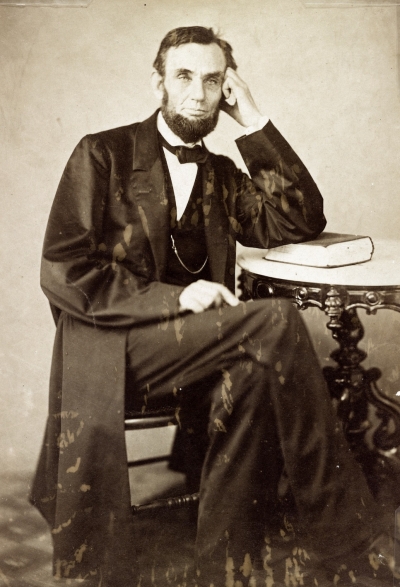

Abraham Lincoln in 1860

Abraham lincoln had a great reputation for humor. He cracked jokes constantly—often painfully bad ones, as when he said after examining a model of the design for the ironclad warship USS Monitor, “All I have to say is what the girl said when she stuck her foot into the stocking. It strikes me there’s something in it.”(1) Even before informing his Cabinet of his momentous decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln first read an article, “High-Handed Outrage at Utica,” by the noted humorist Artemus Ward—much to the annoyance of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.(2)

But Lincoln’s humor often functioned as a way of masking the depression that plagued him most of his life, a condition he often called “the hypo”—short for “hypochondriasis,” a term now mainly associated with anxiety about imagined illnesses (hypochondria) but once synonymous with melancholy. Joshua Wolf Shenk, perhaps the closest student of Lincoln’s depressions, considers him to have suffered the classic symptoms of clinical depression on several occasions, with the age of onset at 26, soon after the death of Ann Rutledge, the object of what may have been his first serious love affair. This might have been classified as simple grief but for suicidal ideations so frequent and intense that friends kept close watch on him for fear that he might kill himself.(3)

Today Lincoln’s depressions would certainly be a political liability; in 1972 reports that U.S. Senator Thomas Eagleton had been treated for clinical depression forced Democratic presidential nominee George McGovern to drop him as his running mate. But Shenk, in his book Lincoln’s Melancholy (2005), maintains that in Lincoln’s own time, his depressions made him a sympathetic figure. A biographical article published soon after his election to the presidency observed that Lincoln had once been so despondent that his friends “placed him under guard for fear of his committing suicide,” but used the episode as an example of Lincoln’s ability to triumph over adversity.(4) Shenk takes a similar view. Lincoln, he writes, “learned how to articulate his suffering, find succor, endure, and adapt…. [H]e forged meaning from his affliction so that it became not merely an obstacle to overcome, but a factor in his good life.”(5) Or as the subtitle of Shenk’s book puts it, depression not only challenged Lincoln but “fueled his greatness.”

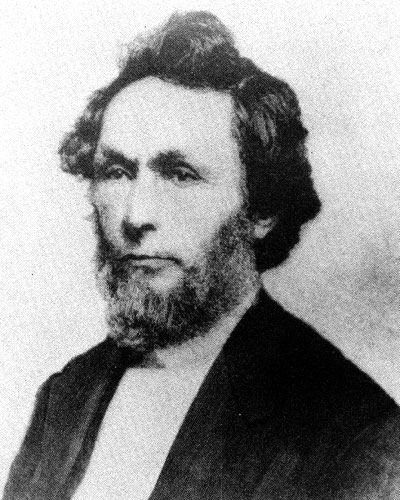

I am not at all sure that I believe this. Having experienced clinical depression for most of my life, I have found it to be uniformly debilitating and redeemed only by the opportunity it has given me to advocate on behalf of others who suffer from mental illness. It is for me, as it was for novelist William Styron, “a howling tempest in the brain,” and this I think is the more usual experience of those it attacks.(6) Andrew Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon, a classic exploration of clinical depression, himself grapples with the disorder and has it more nearly correct: “[T]here are boundaries on resilience. I would not vote for a fragile president. I wish this weren’t so. I couldn’t be president, and it would be a disaster if I were to try. The few exceptions to this rule—Abraham Lincoln, or Winston Churchill, each of whom suffered from depression—used their anxiety and their concern as the basis for their leadership, but that requires a truly remarkable personality and a particular brand of depression that is not disabling at crucial times.”(7) Those qualifiers surely apply to Lincoln, particularly an aspect of his personality famously pointed out by his longtime law partner William H. Herndon: “His ambition was a little engine that knew no rest.”(8)

William H. Herndon

Nevertheless, within the American Iliad, Lincoln’s melancholy is a famous and enduring part of his image. Herndon himself claimed, “He was a sad-looking man; his melancholy dripped from him as he walked…. Lincoln’s melancholy never failed to impress any man who ever saw or knew him.” Herndon attributed this characteristic despondency to two things: “the endless series of troubles in his domestic life”—Herndon detested Lincoln’s wife, Mary Todd Lincoln—“and the knowledge of his own obscure and lowly origin.”(9) Herndon might have added the deaths of two of Lincoln’s sons in childhood: Edward in 1850 at age 3 and Willie in 1862 at age 11.

Another alleged source of Lincoln’s depressions was the doomed relationship with Rutledge, whose death from typhoid fever at age 22 is supposed to have triggered the suicidal ideations that caused his friends such alarm. Lincoln’s biographers differ as to the extent of his love affair with Rutledge—and whether it was indeed a love affair—but it is a staple of the Lincoln legend and the inspiration for Edgar Lee Masters’ well-known poem, in which Rutledge speaks from the grave to say in effect that she is the source of Lincoln’s greatness, that the “deathless music” of “With malice toward none, with charity for all” originates with her, as well as “the forgiveness of millions toward millions”; that she was “wedded” to Lincoln, “not through union, but through separation.” She concludes triumphantly, “Bloom forever, O Republic, / From the dust of my bosom!”(10)

Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War

The poet Stephen Vincent Benét also invokes Lincoln’s depression in John Brown’s Body, his epic book-length poem about the Civil War. In a long passage midway through the work, Benét conjures a soliloquy in which Lincoln waits for word of the outcome of the Battle of Antietam and says at one point, “I’ll get the hypo, sure, / Unless I watch myself, waiting for news. / I can’t afford to get the hypo now, / I’ve got too much to do.”(11)

Lincoln is the closest thing we have to an American saint, and the emphasis on his depression suggests a connection with Jesus Christ, whom Scripture describes as “a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief.”(12) And ultimately it is Lincoln’s melancholy that distinguishes him from America’s other wartime presidents—from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s jaunty optimism, for example. For the Civil War is unlike any of the nation’s other conflicts. It was a tragedy, and Lincoln’s melancholy has such a grip on the American imagination because it seems to recognize so deeply and fittingly the extent of that tragedy.

MARK GRIMSLEY, A HISTORY PROFESSOR AT THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY, IS THE AUTHOR OF SEVERAL BOOKS, INCLUDING AND KEEP MOVING ON: THE VIRGINIA CAMPAIGN, MAY–JUNE 1864 (2002) AND THE HARD HAND OF WAR: UNION MILITARY POLICY TOWARD SOUTHERN CIVILIANS, 1861–1865 (1995). HE HAS ALSO WRITTEN MORE THAN 50 ARTICLES AND ESSAYS.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2020 issue (Vol. 10, No. 3) of The Civil War Monitor.