National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GalleryAbraham Lincoln

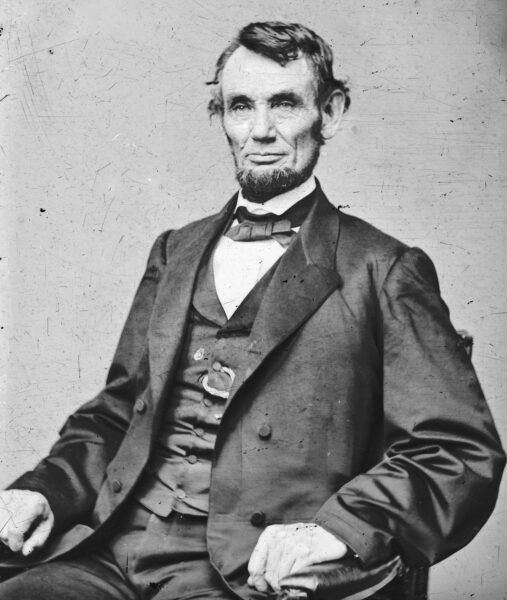

Abraham Lincoln was not a typical president. I’m referring not to his oft-praised leadership skills, but to the literal circumstances of his presidency. Lincoln guided the nation through an exceptional crisis before an assassin’s bullet erased him from the scene. For many Americans at that moment, he became not only a national hero but also a martyr to democracy. Those circumstances have profoundly shaped how we remember Lincoln, and one area where they have been particularly influential is how we value and interpret physical objects and documents associated with him.

There was no presidential library system to retain Lincoln’s records and papers and, up to 1865, his family had been more likely to dispose of old possessions than to preserve them. The suddenness of his death, however, simultaneously boosted both the symbolic and monetary value of such materials. For most people, that meant treasuring a photograph of Lincoln and maybe framing it on the wall, but for those with means it meant Lincoln memorabilia had become collectable. He may have immediately belonged “to the ages,” but Lincoln’s legacy belonged to the American people, and many began making that symbolic relationship literal.

Thus was the world of Lincoln collecting born. Those who had received letters from Lincoln—like young Grace Bedell, who, as an 11-year-old, had corresponded with candidate Lincoln in 1860—suddenly found themselves possessing holy writs. Others who’d received gifts from him or happened to be in the right place to grab something—like Elizabeth Keckly, Mary Todd Lincoln’s seamstress and confidante, preserving Lincoln’s “last spoon”—turned banal objects into remnants of history.

The Lincolns themselves participated in this process and tried to shape it. After witnessing her husband’s murder and death, a devastated Mary Lincoln shut herself in her White House bedroom for weeks. It’s difficult to pin down precisely what she did during that time, but she definitely spent some of it destroying, giving away, and saving various family possessions. In the 17 years until her death in 1882, Mary continued to giving away family relics and even sold them, as in the case of her surreptitious (and fruitless) trip to New York City in 1867 to sell her old clothes—a plan that ended in public humiliation.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressRobert Todd Lincoln

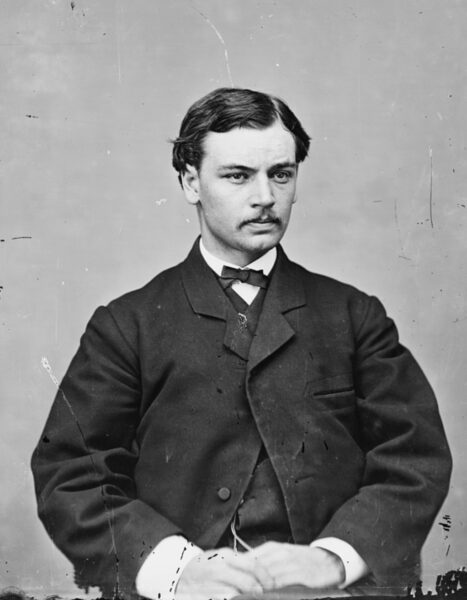

Of Lincoln’s children, only his eldest son, Robert (1843-1926), lived to adulthood, making him the sole bearer of Lincoln’s legacy. Fortunately for posterity, he took this role seriously, especially regarding his father’s possessions. Most notably, it was Robert who ended up owning Lincoln’s personal papers, which he guarded for the rest of his life. Highly aware that biographers and reporters did not always have the best intentions or highest standards, Robert restricted access only to those he trusted—especially Lincoln’s former secretaries John Hay and John Nicolay. He ultimately deeded the papers to the Library of Congress but with an embargo against opening them until 21 years after his own death. Robert similarly sold the Lincoln family home in Springfield to the State of Illinois for $1 and a promise that entry to the house would always be free. In these and other ways, Robert showed he understood the symbolic weight of these possessions and the enormity of his family’s legacy—making them available to succeeding generations.

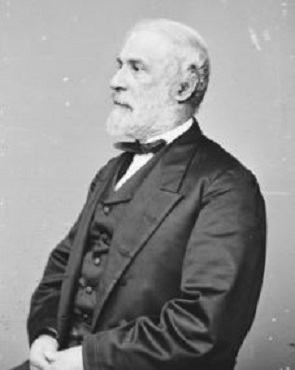

But what about the broader world of Lincoln collectors? The earliest of them are the most difficult for us to understand because their priorities differed from ours. Historical objects today possess interpretive and monetary value and while sometimes those don’t align, most of us agree on what makes a historical object interesting and/or expensive. A letter by Lincoln discussing his views of slavery, for instance, has high interpretive value while a pair of his glasses might have more monetary value because it has greater visual impact. Many of the earliest Lincoln collectors, however, had less regard for historical significance and placed a much higher value on symbolic heft—especially actual pieces of Lincoln, like locks of his hair. Lincoln’s last law partner and first major biographer William H. Herndon, for instance, owned the former president’s “ciphering book”—in which the adolescent Lincoln scribbled his earliest known writings to teach himself mathematics—but went on to nonchalantly rip out each individual page and give them away, leaving them (still) scattered across the country.

Wikimedia Commons

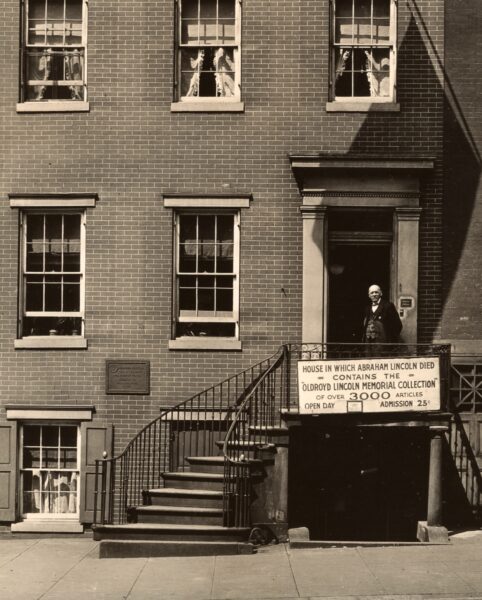

Wikimedia CommonsOsborn Oldroyd stands outside his Peterson house museum in 1925.

By the late 19th century, collectors had less direct connection to Lincoln and began to behave more like what we would expect today—both good and bad. Union army veteran Osborn Oldroyd embodied many of these aspects as he built one of the largest and most public collections of Lincolniana. He even took up residence in Lincoln’s Springfield home—paying rent to Robert Lincoln—and crafted a sort of museum on the first floor while he lived upstairs where the Lincolns had slept. It’s hard to distinguish how much Oldroyd saw himself as a shepherd of Lincoln’s legacy but some of his choices indicate something crasser, like hanging a portrait of John Wilkes Booth over the family mantle. Eventually, an apparent combination of impatience with Oldroyd’s antics and Illinois cronyism forced him to set up shop in the Petersen house—the one in Washington, D.C., across from Ford’s Theatre, where Lincoln died.

The 20th century saw a sustained increase in the number of Lincoln collectors and the value of their objects. By midcentury, people such as Illinois lawyer and author Oliver Barrett had built huge collections that accounted for most of the major objects associated with Lincoln not already housed in museums or other repositories. Indeed, as fewer Lincoln items became available, the market expanded and objects like books, artwork, and political ephemera became more valuable. By the end of the century, Lincoln collecting was so prominent that even historical forgeries became commodities. These trends grew alongside and often intersected with (for better or worse) the creation and preservation of public collections for display and research, which helped professionalize the practice and improve methods for determining provenance—such as, for instance, distinguishing genuine Ford’s Theatre playbills from the numerous fakes.

By the 21st century and the arrival of eBay and online auctions, Lincoln collecting had become big business and available to many more people. This is a blessing and a curse for someone like me. On the one hand, the voracious appetites of collectors have unveiled almost every extant Lincoln document and object. That makes projects like the wonderful Papers of Abraham Lincoln Digital Library (papersofabrahamlincoln.org) possible, because its staff (including me for about 7 years) can easily locate, scan, and digitally publish a large corpus of Lincoln’s writings and incoming correspondence to serve up to everyone for research. On the other hand, this constant hoarding and selling has led to consistent price inflation, putting many of these objects out of reach of most repositories—where most people would get to see them. I can personally vouch for the power of holding a copy of the Gettysburg Address written in Lincoln’s hand, but because of this broader world of Lincoln objects, you’re also acutely aware of its immense material value. That duology—collecting as an act of reverence but also of investment—is present with all historical objects, but seems especially prominent and influential in the Lincoln world. He mostly belongs to all of us, but sometimes to just a few.

Christian McWhirter is a historical consultant and currently serves as the Historical Initiatives Consultant for the Lincoln Presidential Foundation. He previously served as the Lincoln Historian for the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum and editor of the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association.

Related topics: Abraham Lincoln