Library of Congress, colorized by CWM

Library of Congress, colorized by CWMBrigadier General Quincy Gillmore

For Brigadier General Quincy Gillmore, an engineer by profession, the math didn’t compute. His Union force had bombarded the temporary sand fort blocking his path to Charleston in the summer of 1863 with more than 75 tons of artillery shells—more than 25,000 pounds of heavy ordnance per acre of sand. He had coordinated with the navy, whose big guns provided a devastating crossfire into the Confederate battery. His infantry massively outnumbered the defending Rebels, yet the South Carolina fort could not be taken.

At Fort Pulaski, a year before, this type of shelling humbled that seemingly unconquerable brick citadel in a single day, and Gillmore lost not a single man in assaulting and capturing the protector of Savannah. Now, facing a much smaller battery on Morris Island, he ordered what would be one of the more famous infantry assaults of the Civil War, all targeted at what he presumed was a devastated fortification with a diminished and demoralized garrison. Instead, as the onrushing Federal soldiers soon learned with tragic results, the fort’s garrison, hiding in the fine sand, was still well over 95 percent effective and the sandy parapets, though battered and blown around, were as strong as ever. The assault resulted in more than 1,700 casualties, a stunning 90 percent of them Gillmore’s men. The renowned 54th Massachusetts Infantry, honored with leading the charge, would lose more men in the attack than would the entire Confederate garrison.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAfter his successful bombardment and capture of Fort Pulaski, the brick bastion located near the mouth of the Savannah River that protected the vital Georgia city, Union Brigadier General Quincy A. Gillmore turned his attention to Charleston, South Carolina, where sand-constructed Battery Wagner on Morris Island would pose a greater challenge. Shown here: A Union soldier stands amid Pulaski’s battered brick walls after its surrender.

The most significant difference between the general’s glory along the coast of Georgia and his disastrous defeat at Charleston was not his new rifled ordnance or any change in tactics or increase in firepower. It was sedimentary geology. Gillmore, always the coastal engineer, searched for answers in the sediment—the brilliant quartz sand used to construct Battery Wagner—and produced report after report for his colleagues and superiors about the defensive force-multiplying effects of that granular material.

On Morris Island, sedimentary geology had an underappreciated influence in the stubborn Confederate defense, but in all theaters of the Civil War sediments had a profound effect on aspects of strategy, tactics, and combat. Their influence as a force multiplier, morale killer, or even weapon has largely been overlooked by historians. Sediments, in the form of clay, silt, sand, pebbles, cobbles, and boulders—at their simplest, solid matter moved by water, wind, or ice—are as limitless in supply as they are versatile in function. Their effect was determined by the grain size and composition of the particles. On defense, any type of sediment could be piled to provide soldiers with cover and concealment and, during the same fight, sediment might be exploited on offense, using fragments of rock, or clasts, as weapons. At Second Manassas, for example, members of the Stonewall Brigade, who were defending Stony Ridge, threw stones at Union troops when they ran out of ammunition. Confederate troops rolled boulders down the side of Kennesaw Mountain to defend against an attack. Along the trenches at Petersburg, troops on both sides tossed handfuls of sand as a means of temporarily blinding close-quarters attackers.

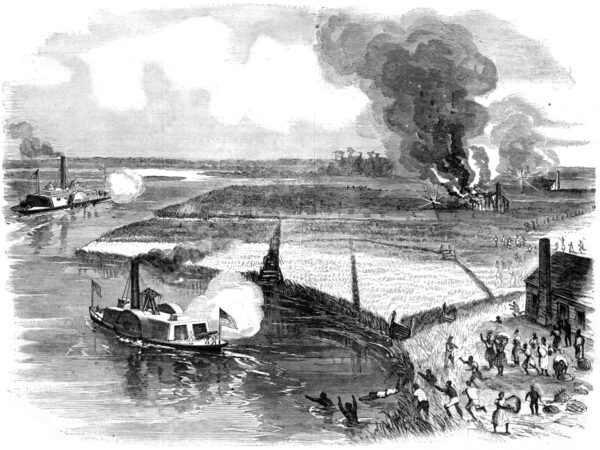

USAHEC

USAHECA depiction of Union soldiers cheering on the bombardment of Fort Pulaski.

Sediments can make weapons more deadly or undermine their damaging effects. If an exploding artillery shell hits very coarse sediment, a new, rocky shrapnel will result, but if the same shell strikes fine-grained sediment, it can be rendered nearly harmless. Fine, penetrating sediment can also make a rifle musket as useful in combat as a nine-pound club. Sediments were occasionally used for camouflage—painting the sides of a ship with dark Mississippi mud before night combat, for example—but changes to the color of a sediment might also be an indicator of danger, like the lighter-colored disturbed sand above a recently buried torpedo (land mine). The dual nature of sediments even influenced soldiers on the march. When large volumes of water were added, soldiers’ boots, cannon, mules, and wagons would sink, along with their morale, while the drying of the same sediment resulted in a second, even more loathed, irritant: dust.

Large sediments were stacked by the hundreds of thousands at Gettysburg to build fortifications or breastworks. Smaller sediments were excavated in the trillions to produce the trenches of Vicksburg and Petersburg and piled in the quadrillions along the coastlines to turn beaches into fortresses. While sedimentary geology had obvious effects on the fighting along the muddy Mississippi and in the silt hills of Vicksburg, other fine grain sediments (such as sand, with a grain size of about a millimeter in diameter) had an even greater impact. In Charleston, the commanding officer in charge of the city’s defenses, P.G.T. Beauregard, heard reports of Pulaski’s decomposition before the rifled guns of the Union army and began to reconsider his strategic plans. He determined to strengthen the city’s defenses with sediment. Sand and soil would be primary building materials, with a defensive line constructed across James Island to protect the city from a Federal advance from the south. New sand forts were constructed on Morris Island, and sand was added to the brick scarp of Fort Moultrie. Unfortunately, sand reinforcement would not extend to Fort Sumter: That bastion’s occupation of nearly every square foot of its artificial riprap island precluded the addition of a protective sandy parapet.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated History of the Civil War

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated History of the Civil WarIn 1863, as Gillmore formulated his plan for taking Charleston, he was aware of the failed Union attempt the previous year to advance toward the city by the way of James Island, where David Hunter’s forces had been defeated soundly at the Battle of Secessionville.

The largest and most complex of Charleston’s sand batteries was constructed across the width of Morris Island, the barrier island that marked the southern border of Charleston Harbor. The Neck Battery, as it was originally called, carried a descriptive name. The fortification crossed the narrowest portion of Morris Island, spanning from Vincent’s Creek in the back-barrier marsh to the strand line of the Atlantic Ocean. The battery design took full benefit of the natural geomorphological advantages each of the Morris Island sub-environments offered.1

Confederate engineers assigned to build these temporary fortifications knew that every single portion of a barrier island could be used as a defensive force multiplier. Attack was impossible from the ocean or across the broad, muddy marshes, so the defensive firepower of any battery or fort could be concentrated along the length of the island in one direction. The inlets that defined the ends of the island also made offensive maneuvers difficult. The inlets along the Charleston coast can be classified as either fluvial (river) barrier inlets or tidal barrier inlets, depending on the relative influence, strength, and interaction of the local rivers or tides. The nature of the inlet, whether tide- or river-dominated, was an important consideration for movements of both troops and shallow-draft ships along the shoreline. The ebb-tidal delta associated with larger inlets also prohibited use of most deeper-draft, oceangoing vessels near the islands, making naval support of land operations more challenging.2 The water velocity associated with larger tide-dominated inlets generally prohibited cross-inlet movement by troops, as the boats would have been carried in a shore-perpendicular direction offshore (or, in a rising tide, toward the mainland).

When Gillmore considered his options, he was aware of the earlier failed assault against the south side of the city. The previous summer, Major General David Hunter and his 7,000 infantry attacked the Confederate fortifications on James Island during the Battle of Secessionville. That assault was centered on the Tower Battery, a small sand fort that was constructed across a half-mile-long sandy ridge. Marshes covered both flanks of the ridge (and battery) to the north and south. The commanding officer in the fort, Colonel Thomas Lamar, would lead the defensive resistance in the stronghold that would later adopt his name.

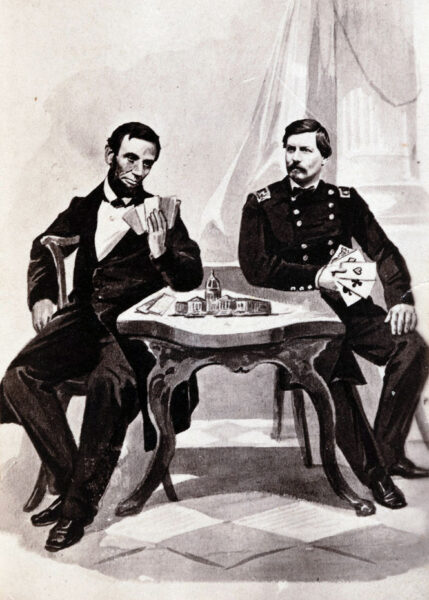

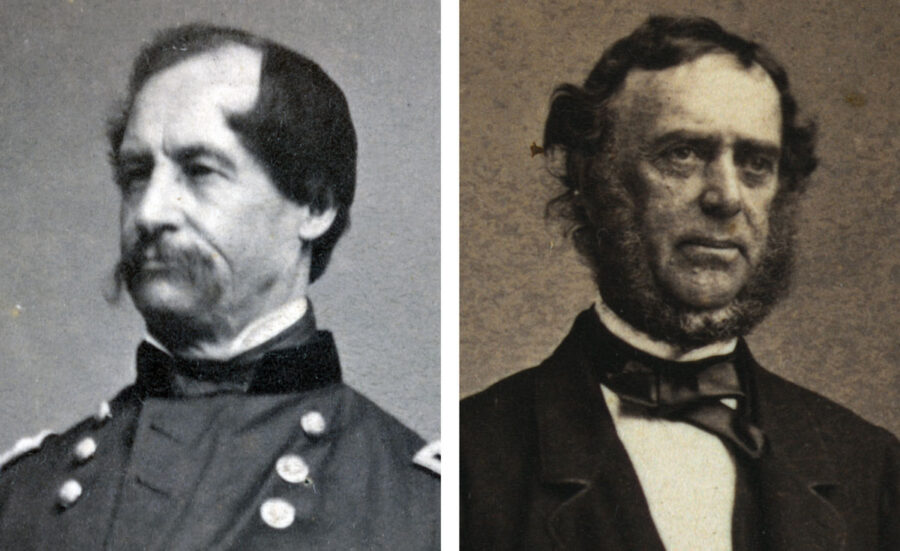

Library of Congress

Library of CongressDavid Hunter (left) and Samuel Francis Dupont

During this fight, the immensely outnumbered Confederates benefited from the local geomorphology and sedimentology at almost every scale. The distribution of Pleistocene sand ridges and impassable muddy marshes dictated the Federal route of approach and restricted the size of the attacking infantry force. As a result, the Confederate artillery was completely concentrated along the axis of the ridge, entirely in one direction, understanding that the probability of attack from the marshes to the north or south was negligible. The flat marshes and linear, gently sloping sandy ridges also provided excellent fields of fire for the Confederate guns. This small change in relief resulted in little potential cover or concealment for the Union infantry. As the 8th Michigan, 7th Connecticut, and 28th Massachusetts infantry regiments began their attack, the men discovered that the sand ridge narrowed as it approached the battery, with marshes encroaching on both sides. As the assault approached the battery, the Federal lines became more and more constricted and entangled, with the flanks dragging across the softer, muddier ground. Despite these sedimentary challenges, the Union infantry still managed to reach the sandy parapet, but with a much diminished striking force. Fierce fighting took place between a small number of Federal infantry and Confederate artillerymen on the parapet walls and superior slope, and a Union flanking move was attempted to support the attack. This tactical maneuver failed to develop when the men became bogged down in the soft, cohesive sediment of the muddy marsh and Confederate reinforcements reached the rear of the battery. The disastrous assault was over after less than an hour of fighting. The Federals would try a second assault on the battery from the north on James Island, but it too was compromised by the presence of the marshes and their impassable sticky mud. During the battle, Hunter lost more than three times as many men as the Confederate defenders, suffering more than 680 casualties. The role of sedimentary geology in the fight was later described well by local historian Warren Ripley: “The Confederates celebrated their victory, but the real salvation of Fort Lamar lay in mud—gooey, bottomless pluff mud—and luck.”3

After the debacle on James Island, Union efforts to reduce Fort Sumter and capture Charleston Harbor were transferred to the navy. In the spring of 1863, the commanding officer of the South Atlantic Blockade Squadron, Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont, decided to test the masonry defenses around the entrance to the harbor. His attack would employ the newest weapons in the fleet, his improved monitors, to steam up the harbor channel and attack Fort Sumter from a path adjacent to Morris Island.

Poor weather delayed the initial assault, intended for the first week of April. The timing of the offensive was critical for the underpowered ironclads: the tides in Charleston Harbor often exceeded 6 feet per second, while the top speed of the Federal vessels only ranged between 10 and 15 feet per second. The flotilla needed to remain in proper line of battle to ensure a coordinated attack, so they could not exceed the maximum velocity of the slowest vessel. The combination of a relatively narrow and hazardous sand-filled channel, strong currents, and massive quantities of incoming enemy artillery rounds doomed the attack from the start. When the tides began to shift, DuPont realized that any of his damaged warships were in danger of being carried by the currents even closer to the enemy guns. He had no choice but to call off the attack and retire farther outside the harbor entrance. Before he did, the Confederates had fired 2,200 rounds with impressive accuracy: Almost 25 percent of the shells struck iron and wood, although only one Federal vessel was lost.

It was now clear that the capture of Charleston would not be possible using naval firepower alone. In fact, no Federal flotilla was successful in suppressing even a single Third System fortification (a series of 42 massive brick and stone forts constructed between 1816 and 1867 by the U.S. government to protect against an amphibious invasion) during the entirety of the war. Instead, a combined strike from the army and land-based heavy artillery, with the full support of naval guns offshore, would be required for any future successful Federal assault against the city and its defenses.

To give the navy better odds of successfully running the crossfire gauntlet between Forts Moultrie and Sumter, and navigating over and around multiple underwater obstacles, Gillmore proposed a strategy derivative of his successful plan at Savannah. Instead of Tybee Island in Georgia, Gillmore would place his firepower on Morris Island. Heavy land-based rifled artillery would be used to demolish Fort Sumter, shifting the offensive advantage back to the navy. With Federal ironclads in the harbor, the city that started the Civil War would have little choice but to surrender.

Gillmore, whose army was camped on Folly Island, selected Brigadier General George Strong to lead the beachfront assault across the inlet to the southern shores of Morris Island. Strong would command half of Gillmore’s available infantry, a force in excess of 5,000 men. They would use the Folly River to enter and cross the inlet above the ebb delta to land at the beach on the southern end of Morris. All of this would be done while under fire from Confederate artillery and, when the range closed, infantry. Suppressive fire for this exposed flotilla would be supplied by Federal artillery on Folly Island, the naval gunboats offshore across the ebb tidal delta, and several Dahlgren boat howitzers. The diminutive boat howitzers would sail with the amphibious flotilla, offering close, if limited, artillery support. In total, Strong had an initial waterborne assault force of around 2,500 infantry, with a reserve on Folly Island of another 2,800 men.

At daybreak on July 10, the Federal batteries on the north end of Folly Island opened fire, exposing their position for the first time to the Confederates a half-mile away across the inlet. The Rebel batteries on Morris soon replied, and an hourlong duel began. As shot and shell flew back and forth across the inlet, Strong’s boats remained hidden behind the reeds of the back-barrier marsh. Around 6:30 a.m. the Union monitors Catskill, Nahant, Montauk, and Weehawken joined the fight. The enfilading naval gunfire from offshore to the east proved devastating to the Confederate position, with grapeshot and shells tearing along the long axis of the Rebel batteries and rifle pits. Soon Confederate return fire diminished and the Federal boat howitzers entered the fray from the opposite direction, sailing downriver toward the inlet with Strong’s infantry-filled barges following closely behind. Strong ordered his force to land along the beach on the western end of the Confederate entrenchments. The first wave of Federals ashore carried new seven-shot Spencer repeating rifles, an ideal weapon for assaulting an enemy concealed in rifle pits—assuming a soldier could keep the mechanically complex gun away from the beach sand. Other regiments followed closely behind, rapidly crossing the 100-yard-wide beach. Fierce hand-to-hand combat in the trenches and rifle pits led to the wounding of the local Confederate commanding officer, and the Rebel defensive line soon collapsed.

As the primary Federal assault was proving efficacious, the 6th Connecticut Infantry, which had landed farther toward the ocean along the inlet, began fighting across the beachfront to the north. From this position the men began attacking the vulnerable Rebel gun batteries from the rear. Once the artillery positions were overwhelmed, the remaining Confederate infantry was nearly surrounded. The shattered southerners determined that the only viable path to survival was a rapid retreat to the north through the 35-foot-high sand dunes to the protection of the heavy guns of Battery Wagner. Strong ordered his men to pursue the routed Rebels and, if their momentum allowed, to seize the fortification. The exhausted Federal infantry made a valiant attempt, but the combination of long-range solid shot from Fort Sumter and grapeshot and canister from Wagner ended their pursuit. Certainly the midsummer heat and the difficulty of running across dry, fine dune sand helped foil the effort.

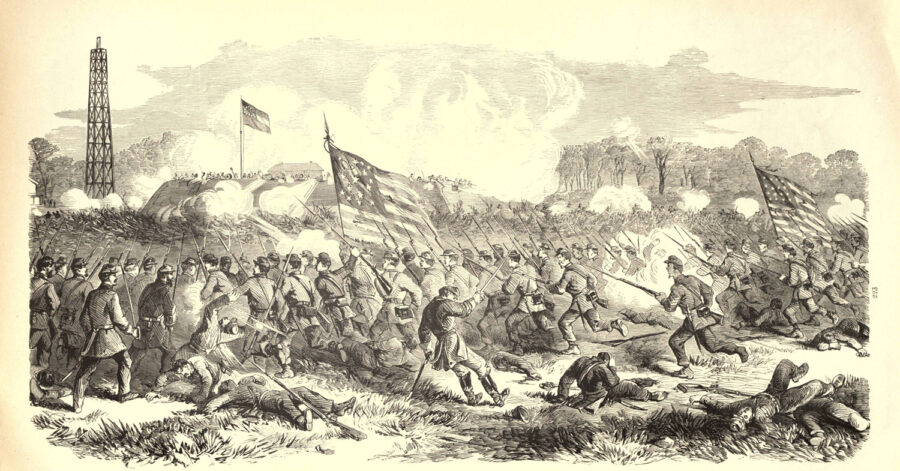

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated History of the Civil War

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated History of the Civil WarAfter failed attempts to take Battery Wagner on Morris Island by direct infantry assaults, Gillmore opted to dig in to conduct a more extensive siege. Wagner is shown here sometime after its Confederate garrison abandoned it in September 1863.

With the southern half of Morris Island now secured, Gillmore’s orders for the next morning, July 11, demonstrated his lack of respect for the sand battery to his front. The 9th Maine, 66th Pennsylvania, and a portion of the 7th Connecticut infantry regiments were ordered to attack the fort, with the assault being conducted directly along the beach. Gillmore was also apparently unaware that the Confederate garrison had been bolstered by reinforcements arriving the previous day. Strong assembled his men into columns for the attack, with four companies of the 7th Connecticut in the lead. The men were to attack into the face of the Confederate artillery and small arms fire over a narrow isthmus of sand that was bordered to the east by the Atlantic and to the west by a low marsh. The Confederates had additionally deployed skirmishers in the sand ridges 100 yards in front of the battery. At dawn the next day, these pickets provided the first alert of the coming Federal attack. Strong’s force moved up the beach in two columns separated by the strand line. They were met with sustained Confederate fire, yet they were able to cross the battery’s moat and scale the parapet. Unfortunately for the men from New England, however, the initial surge of the Connecticut men was not well supported by the 9th Maine or 66th Pennsylvania, and the assault faltered. The Union lost almost 400 men in its first organized attempt to capture Battery Wagner. Nevertheless, Gillmore decided it was still conceivable, and preferable, to capture the sand fort without initiating a protracted siege.

During his next attempt to smother the Confederate defenses, Gillmore would combine a land-based cannon fusillade with gunfire from the navy’s heaviest artillery to disable the guns in Wagner. With the firepower of the battery diminished and the Confederate garrison severely wounded, his next and larger attack would certainly meet with success. Gillmore brought forward more than 30 heavy artillery pieces to be assembled within range of the sand fort. These guns were scattered across southern Morris Island and Black Island, an older barrier island. These guns would be less than a mile from Wagner and, when the ironclads opened up, would provide a presumably deadly crossfire.

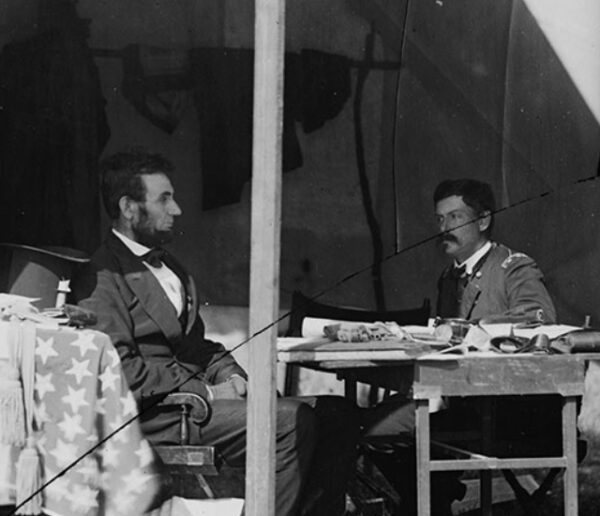

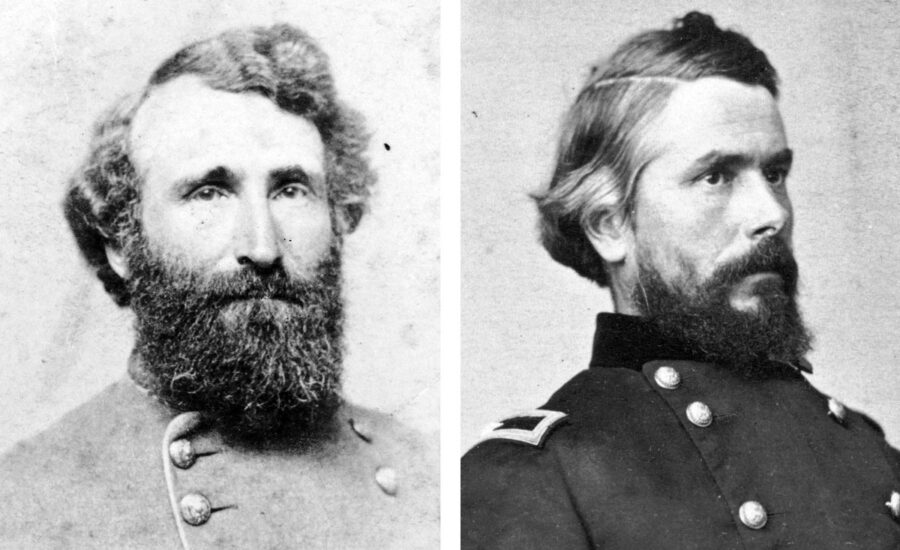

Library of Congress

Library of CongressWilliam Taliaferro (left) and Truman Seymour

As Gillmore sited his artillery, Confederate general William Taliaferro, the commanding officer on the island, was receiving reinforcements. He now had more than 1,250 men to resist the anticipated Union attack. As he surmised, scattered ranging shots began to fall on and around his position on the morning of July 18. By noon the Federal bombardment had commenced in full, raining shells at two-second intervals, and soon the fort’s guns ceased returning fire. In a pattern that was repeated multiple times during the Civil War, this lack of counterbattery and return fire was mistakenly interpreted as a sign that the enemy’s guns had been destroyed, instead of an attempt by the gun crews to conserve ammunition in anticipation of an imminent infantry assault.

In Battery Wagner, however, nine-tenths of the Confederate batteries were still intact post-bombardment, although many of the pieces were covered in sand. The garrison remained sheltered in the fort’s large bombproof. Gillmore conferred with Brigadier General Truman Seymour, the man who would lead his next assault, about the most favorable path for the 6,000-man-strong attack. The generals concurred that the advance should begin at dusk, allowing just enough daylight for the men to find their way between the dunes and the waves while minimizing the visibility of the attacking force to the Confederate gunners. The 54th Massachusetts Infantry, a regiment composed of 600 African-American troops who had performed admirably the previous week during fighting on James Island, would lead the assault. Land-based artillery continued to provide suppressive fire as the Federal infantry shuffled down the beachfront. The onrushing men now faced the familiar problem witnessed at Secessionville: Beach sand is difficult to cross on the double-quick, and the island grew narrower just in front of the battery, forcing the men to compress ranks and become an invitingly dense target for the Confederates. Their progress was slowed by the flanking wet sand and marsh mud, and disorganization began to become apparent in the overlapping columns. In a confused and uncoordinated night fight, the men from Massachusetts traversed the sediment-filled moat and climbed the southern face of the battery. Here their leader, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, and two of the regiment’s captains were killed on the parapet. The 48th New York and 6th Connecticut infantry regiments entered the fortification closer to the sea face of the battery, and they found it only lightly guarded by scattered defenders. This segment of the battery had been abandoned during the bombardment by North Carolina troops who had been tasked with holding the Atlantic wall. The Federals continued to ascend the parapet along the eastern side of the battery and entered the fort, but maneuvering in the dark greatly diminished their organization and momentum. As supporting Union infantry crossed the beach toward the battery, friendly fire soon began to add to the Union casualties and only intensified the confusion. Seymour called for more reinforcements to be thrown into the attack, but Gillmore demurred. By midnight the assault was over, and what was left of the 54th Massachusetts entrenched at a rallying point just outside of rifle range of the fort.

Gillmore’s reaction to this ghastly defeat on the beach was to dig in, preparing to conduct a more extensive siege. On the southern end of Morris Island, a palisade was constructed in case of an unlikely Confederate counterattack, and several new heavy artillery batteries were added to the Union position. It was during this time that one of the key sedimentary hazards of constructing gun batteries in dune sand became apparent. Brigadier General J.W. Turner described the “serious evil” of sand and how it was responsible for the bursting of his guns: “The material of our field works upon Morris Island was dry, hard, flinty sand, which in a windy day was constantly blowing about, and at times to such an extent did it fill the air, that it was a most severe annoyance to officers and men. On such occasions it was almost impossible to keep the pieces free from it.”4 Apparently the sand was better at silencing the Federal guns than were the Confederates.

Gillmore used two of these new batteries to harass the garrison in Battery Wagner, while the remainder of his artillery was concentrated on Fort Sumter. The four ironclads sailed closer to shore to join the shelling of Wagner and Sumter from a different direction. On August 17 the combined land- and water-based artillery launched more than a thousand shells into Fort Sumter, disarming seven of the fort’s remaining guns and severely breaching the brick walls. By the end of the bombardment, Fort Sumter was reduced to a single tier of rubble and could no longer offer any support for the men in Wagner. Concurrently with this artillery action, Federal sappers and infantry gradually dug approach trenches through the soft sand to Battery Wagner along the center of Morris Island. These entrenchments zigzagged their way toward the battery so that Confederate sharpshooters and artillery in the sand fort were never provided a clear shot down the length of the trench. The Federal sappers also constructed a large battery in a location that would have been thought impossible earlier in the war: the middle of a back-barrier marsh. Sandbags and pilings were used to build a supporting platform across the mud.5 These pilings needed to be driven through the soft marsh sediment to reach the less compressible Pleistocene sands below, or the platform would never support the weight of the 200-pound Parrott rifle or its ammunition. This massive cannon, dubbed the “Swamp Angel,” began firing incendiary rounds at downtown Charleston within a week of its completion, the first deliberate targeting of a civilian population during the war. (The cannon exploded after three dozen rounds.)

Gillmore ordered another strike against Battery Wagner after Fort Sumter had been reduced. Colonel George Dandy was instructed to capture the Confederate rifle pits immediately below the earthworks with the men of the 100th New York Infantry. They were momentarily successful, before a Confederate counterattack forced a withdraw. After this demonstration of the vulnerability of these advanced earthworks, the Confederates began digging to improve their forward entrenched position. Before this was accomplished, however, the Rebels were again attacked and overrun by the 3rd New Hampshire and 24th Massachusetts infantry regiments. The Federals then began to modify and reverse the former Confederate rifle pits, and this position was converted into the closest siege line yet to the adjacent fort. This new siege line was well within rifle range of the battery and, importantly, was north of the marsh constriction that had compressed and mired the earlier infantry attacks on the earthworks.

Gillmore prepared for a third assault on the fort, which he scheduled for September 7. The attack was to concentrate on the seaside sector of the battery, with supporting troops shifting around the eastern wall of the fort and attacking the weaker rear of the works. On September 5, Gillmore and Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren commenced a day-and-a-half-long bombardment of the battery, once again hoping to weaken the Confederate defenses prior to attack. The effect of this bombardment was greater: Wagner’s bombproof magazine began to become exposed under the shifting sand. This vulnerability, combined with the proximity of the Union siege lines, convinced the garrison commander, Colonel Laurence Keitt, that the sand fort should be abandoned once the shelling ceased. With Battery Wagner undefended, Battery Gregg, with artillery that faced toward Charleston Harbor, was untenable. As a result, the final Confederate defenders of Morris Island left Cummings Point on the evening and early morning of September 6 and 7. When Federals captured two of the Rebels’ evacuation boats, Gillmore was alerted that Morris Island was now exclusively occupied by his men. The cost had been extraordinary. The Union lost almost 2,500 men trying to capture an elaborate pile of sand. The Confederates lost only 640 men, demonstrating the force-multiplying effects of the beach and dune sand and the marsh mud, when properly exploited on the defensive.

Charleston, and the pile of debris that had been Fort Sumter, remained in Confederate hands until after William T. Sherman had marched from Atlanta to Savannah. His army would have to choose between two inviting targets in South Carolina: the state capital at Columbia, and Charleston. On Valentine’s Day 1865, Beauregard decided to finally abandon the city, ordering any Confederate troops still around to make their way north to join Joseph Johnston’s army in North Carolina. Two days later Fort Sumter was abandoned. The capture of Charleston had taken 567 days, the longest siege of the Civil War.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAfter establishing additional batteries on Morris Island, Gillmore called for the renewed bombardments of Fort Sumter, Battery Wagner, and Battery Gregg in August 1863 (depicted above in a lithograph by Currier & Ives). The result was the destruction of Sumter and subsequent Confederate abandonment of the defenses on Morris Island.

Gillmore’s experience on Morris Island clearly illustrated many of the different ways that sediments influenced and restricted tactical options and the nature of combat. Gillmore had no choice in the orientation of his attack because of the geomorphology of Morris Island. The ocean and a mud-filled marsh eliminated possible maneuver or flanking; assault from any direction other than the southwest was impossible, and even that was compromised by the soft ground created by a muddy extension of the high marsh just in front of Battery Wagner. As the 54th Massachusetts rushed along the shoreline across the fatiguing, shifting sand, this defile forced their lines to compress, providing an ideal, concentrated target for Confederate artillery and rifle fire.

Sand also essentially destroyed Gillmore’s greatest advantage, his artillery firepower, in large part because he underestimated the strength of the sand: “Against the destructive effects of projectiles, pure quartz sand, judiciously disposed, comports itself unlike any other substance,” he later wrote.6 The strength of a sediment is determined by two factors: friction and cohesion. Sand is especially strong with respect to intra-grain friction, while clay provides a great deal of cohesion.7 When a heavy artillery shell hits a sandy parapet it will penetrate only so far because of the friction provided by the sand. If it explodes, this same friction will diminish the effects of the shrapnel, effectively trapping it harmlessly within the sand. Note that there also aren’t any secondary projectiles associated with an impact in sand, as there would be with almost any other type of material like brick, stone, or wood. Sand parapets are also easy to rapidly repair, if repair is even needed (sand hit by artillery shells often flies vertically, to then settle back into place). Gillmore’s after-battle reports reflect this understanding of the value of sand: “A comparison of the two sieges of Fort Pulaski and Fort Wagner, the former a casemated brickwork, and the latter a sand fort improvised for the occasion, leads to the query whether all of our batteries should not be constructed of a material like sand.”8

Gillmore would later participate in the planning for the assault on a sand fortification an order of magnitude larger than Battery Wagner, and the results of this campaign would be the successful, but also bloody, capture of Fort Fisher, North Carolina, in January 1865. Unfortunately, both fortifications would later fall victim to another type of persistent assault: erosion from ocean waves and storms.

In 1863 Quincy Gillmore spent thousands of artillery rounds and many hundreds of lives attempting to destroy Battery Wagner. Two decades later, as a coastal engineer charged with improving navigation in Charleston Harbor, he would—perhaps inadvertently—eliminate all trace of the fortification when he ordered the construction of two massive sand-stealing jetties across the mouth of the harbor. The results of this engineering project were immediate, as Morris Island was now starved of a drifting sand supply from the north, and the rapid retreat of the island allowed the battery to quickly disappear into the waves of the Atlantic.9

Scott Hippensteel is a Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. His research specialty involves using microfossils and sediments to solve environmental and geoarchaeological problems. He is the author of three books about how science can be used to reinterpret the Civil War, including the recently released Sand, Science, and the Civil War: Sedimentary Geology and Combat (University of Georgia Press).

Notes

1. Geomorphology is the study of how the topography of a region came to be, from a geological perspective.

2. Ebb deltas are subaqueous, triangular-shaped accumulations of sand that are found at the mouths of coastal rivers. They often render the water along the shoreline so shallow that they are exposed during low tides.

3. Warren Ripley, The Civil War at Charleston (reprint, Charleston, 1996,), 35.

4. Quincy A. Gillmore, Engineer and Artillery Operations against the Defences of Charleston Harbor in 1863 (New York, 1865), 155.

5. Sandbags must be considered the one military implement from the Civil War that survives on today’s battlefield in the most unchanged form.

6. Gillmore, Engineer and Artillery Operations, 121.

7. Gillmore tested the strength of sand while on Morris Island. He had his engineers fire Spencer and Springfield rifles into various materials using depth of penetration to quantify the defensive strength of sand parapets compared with those constructed of other materials.

8. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series 1, vol. 28, pt. 1, 35.

9. It should be noted that this same sand, now funneled offshore, almost certainly helped to bury and protect the Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley.