The Second Battle of Winchester: The Confederate Victory that Opened the Door to Gettysburg by Eric J. Wittenberg and Scott L. Mingus, Sr. Savas Beatie, 2016. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1611212884. $32.95.

The famous bloodletting in Adams County, Pennsylvania, on the first three days of July 1863 came after weeks of hard campaigning by Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac. The fighting in and around Winchester, Virginia, the third week of June resulted in one-tenth of the casualties sustained at Gettysburg, but served as a vital element of the maneuvering that brought the two most important Civil War armies to their grand collision. In The Second Battle of Winchester: The Confederate Victory that Opened the Door to Gettysburg, Eric J. Wittenberg and Scott L. Mingus, Sr., offer a new look at the engagement that eliminated the Union military presence in the Shenandoah Valley and cleared the way for Lee’s second invasion of the North.

The famous bloodletting in Adams County, Pennsylvania, on the first three days of July 1863 came after weeks of hard campaigning by Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac. The fighting in and around Winchester, Virginia, the third week of June resulted in one-tenth of the casualties sustained at Gettysburg, but served as a vital element of the maneuvering that brought the two most important Civil War armies to their grand collision. In The Second Battle of Winchester: The Confederate Victory that Opened the Door to Gettysburg, Eric J. Wittenberg and Scott L. Mingus, Sr., offer a new look at the engagement that eliminated the Union military presence in the Shenandoah Valley and cleared the way for Lee’s second invasion of the North.

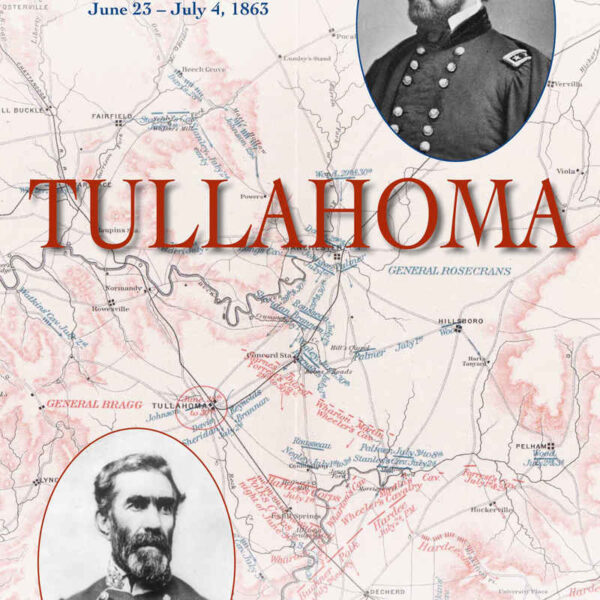

The campaign detailed by Wittenberg and Mingus featured some of the Civil War’s most famous personalities, along with some lesser known but controversial figures. Following the battle of Chancellorsville and the death of Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, Lee reorganized his army, elevating Richard S. Ewell from division to corps command. Ewell took over three divisions from Jackson’s old Second Corps. Those divisions—numbering 19,000 men and commanded by Jubal A. Early, Robert E. Rodes, and Edward “Allegheny” Johnson—collided with Major General Robert H. Milroy’s 6,000 man Second Division of the Union Army’s Eighth Corps in and around Winchester from June 13 to June 15 as the federals struggled to retain a foothold in the Shenandoah Valley.

In order to cross the Potomac and maneuver his troops north, Lee relied on the Blue Ridge Mountains to screen his movements. The only federal resistance in the Valley was Milroy’s small command at Winchester. Milroy, as Wittenberg and Mingus detail, was not a West Point trained officer, receiving his military education at Vermont’s Norwich Academy. As a result, Milroy resented what he perceived as the superior attitude of West Point soldiers and often exerted his own will in contravention of orders from his superiors. For readers interested in learning more about a lesser-known Union officer, the book’s focus on Milroy and his lifelong attempt to defend himself for his failure at Winchester offers an excellent starting point.

Readers interested in developing a greater tactical understanding of the Gettysburg Campaign will also find much to consider in Wittenberg and Mingus’ work. As Ewell advanced on Winchester, he encountered little resistance. Outnumbering the federals three to one, he divided his command, aiming to cut off all escape routes from the city. Milroy had been ordered not to attempt to hold Winchester in the face of a larger enemy, but until Ewell’s three divisions descended on his position, he was not aware of the size of Ewell’s opposing force. Milroy concentrated his soldiers in the fortifications around Winchester, believing they were strong enough to withstand a Confederate attack. Milroy miscalculated, however, as he was outflanked to the left and right. He ordered a retreat, straight into the hands of the waiting Confederates. Ewell reported capturing 4,000 federals, while reporting fewer than 300 causalities for his own army. Wittenberg and Mingus do an excellent job of clearly narrating each phase of the battle and examining the roles of individual brigades and regiments throughout the fighting.

Because of Winchester’s strategic importance, Wittenberg and Mingus have a multiplicity of civilian and military accounts to draw on in their descriptions of the Union occupation of the city and battle. Many of Winchester’s well-known lady “Devil Diarists” feature throughout the book, along with wartime diaries and letters from Union and Confederate soldiers. These accounts enrich the text and help impart a sense of how individuals experienced the action around Winchester in the summer of 1863.

As is often the case in studies of the Civil War, smaller actions such as the Second Battle of Winchester are overshadowed by larger battles. The battle was a tactical masterstroke for Ewell and his subordinates, with Jubal Early performing particularly well— foreshadowing his successful return to the Valley in June and July 1864. Following the battle, Milroy was relieved of his command and sent west, like so many other undesirable Civil War officers. Though the book, at 432 pages of text, may strike some readers as long for an account of a relatively small Civil War engagement, Wittenberg and Mingus have written a readable study of the Second Battle of Winchester that should find an appreciative audience among those interested in the Gettysburg Campaign, the interactions between battlefield and homefront, and Virginia during the Civil War.

Cecily Zander earned a B.A. in History from the University of Virginia; at present, she is a graduate student studying the Civil War and nineteenth century U.S. History at The Pennsylvania State University.