In May and June 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Potomac pushed doggedly toward the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, in the Civil War’s bloodiest military movement: the Overland Campaign. From the Rapidan River to the James and numerous waterways in between, General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia blocked, blunted, or parried every move Grant made. As evidenced by the images below, the work of the photographers and artists who accompanied the armies allows us to take a graphical journey in the footsteps of Grant and Lee through their intitial campaign against each other. (All images courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

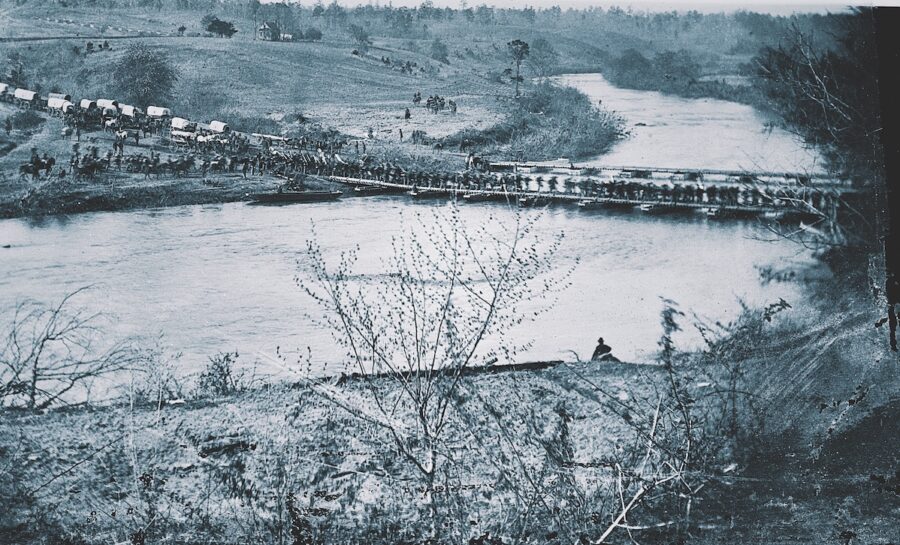

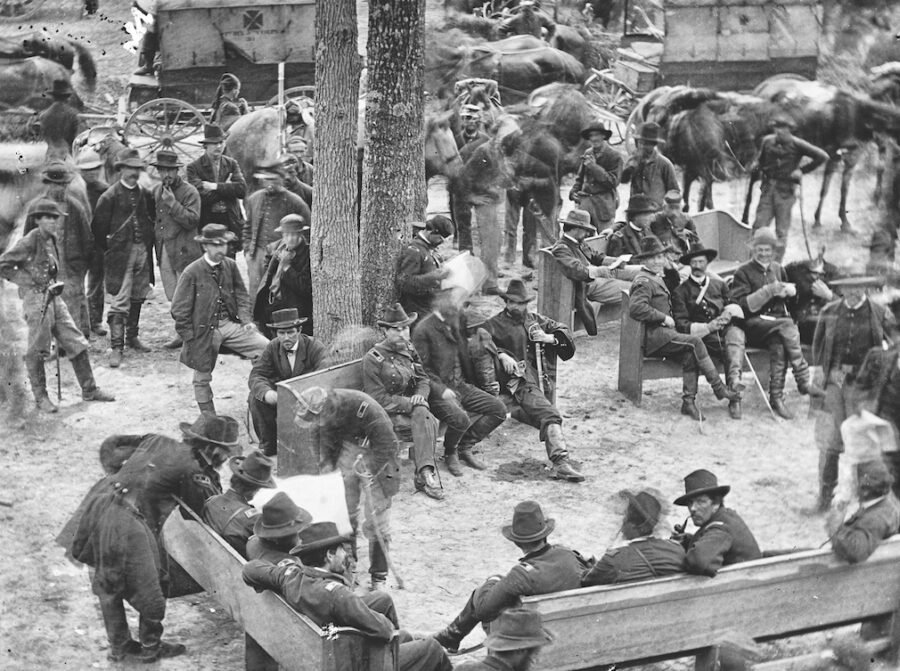

On May 4, 1864, the grand campaign began. Grant aimed to force Lee to abandon his strong Rapidan River defenses by crossing the river beyond the Confederate right flank. Grant’s hope was to then fight Lee on open ground. Photographer Timothy O’Sullivan was there to capture soldiers, beasts, and all the trappings of war as they crossed the Rapidan on two pontoon bridges at Germanna Ford. The blurred motion shows a mass of men from the Army of the Potomac, either the V or VI Corps, about to experience a whole new level of warfare.

Grant’s attempt to maneuver Lee out into the open was unsuccessful. Lee moved from his Rapidan defenses with such speed that Grant was drawn into a horrific battle in the dense second-growth timber known as the Wilderness. Here, movements were difficult, visibility poor, and communications unreliable. The few clearings limited artillery use and helped Lee effectively overcome his numerical disadvantage.

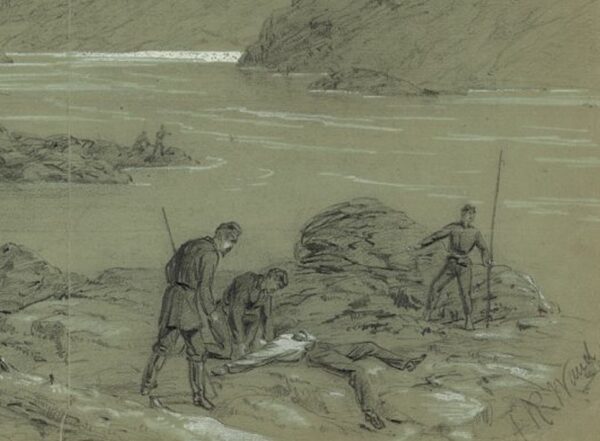

The two days of fighting at the Wilderness produced one of the costliest battles of the Civil War. In some areas, the cries of the wounded grew increasingly desperate as fires roared through the thick timber. The lucky ones got out; some burned to death. Here, sketch artist Alfred Waud depicts Union troops carrying injured comrades from the battlefield—a dramatic scene of motion that a camera of the day simply could not have captured.

Despite being rebuffed in the Wilderness, the Union army continued on toward Richmond, a triumph of will that distinguished Grant from his predecessors who battled Lee in Virginia. When Grant sent General Philip Sheridan’s cavalry to gain control of the roads leading to Spotsylvania Court House, they ran into Confederate cavalry under General Fitzhugh Lee. A furious fight erupted at Todd’s Tavern, shown here just after the war. Although Lee was pushed back, Rebel infantry arrived in time to preserve the Confederate route to Spotsylvania. The tavern itself served as a Union headquarters during the fighting.

The massive armies moved to the next major crossroads: Spotsylvania Court House, where Lee’s men built sophisticated fortifications to help blunt any possible enemy assault. The grandest in a series of Union attacks came on May 12 at the center of the Confederate line upon the salient known as the Mule Shoe, resulting in one of the most savage clashes of the war. Even when photographer G.O. Brown toured the battlefield after the war, the Confederate defenses (some of them shown here) were still impressive.

The fighting at Spotsylvania lasted for days and left tens of thousands of casualties in its wake. In 17 days, Grant’s campaign had already produced two of the five bloodiest Civil War battles. The dead and wounded lay everywhere, including this unidentified Confederate soldier killed on May 19 near Harris Farm. This photograph by O’Sullivan is one of six he took at Harris Farm on the day after the battle fought there; they are the only photos showing dead bodies on the field in the deadliest of all Civil War campaigns.

On May 21, O’Sullivan lugged his bulky camera up to the second floor of Massaponax Church, where Grant and others had stopped as the army moved ever southward. O’Sullivan captured three photos of history in the making. In the scene above, Grant (standing, lower left) is leaning over the right shoulder of General George Gordon Meade, commander of the largest force under Grant’s command—the Army of the Potomac. The two highest ranking Union men in the Overland Campaign examine a map while the army moves past at top.

By predicting Union movements and preserving his lines to Richmond, Lee forced the pursuing Grant into seemingly endless tribulations—longer marches, bridgeless river crossings, dreadful roads, and rugged terrain. After Spotsylvania, Lee took position behind the North Anna River between two crossings, hoping to attack Grant if he split his army in pursuit. Here, some of Grant’s horsemen cross the Chesterfield Bridge over the North Anna.

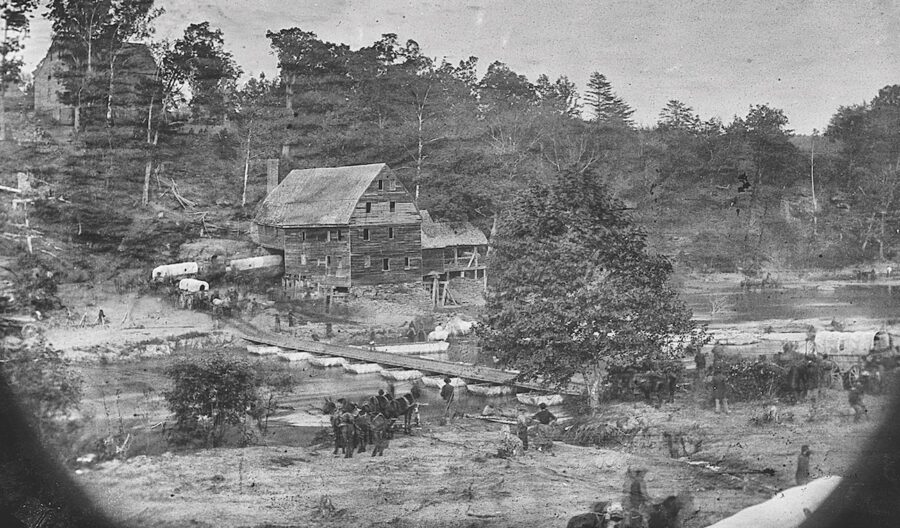

The Union V Corps under General Gouverneur Warren crossed the North Anna on a quickly laid pontoon bridge at Jericho Mill. In this photo, most of the troops (as well as the photographer) have already crossed, and ammunition wagons are preparing to navigate the bridge. Grant had fallen into Lee’s trap, but Lee was ill and his planned attack never took place. Nonetheless, other fighting flared and more than 4,000 men were added to the casualty rolls along the North Anna.

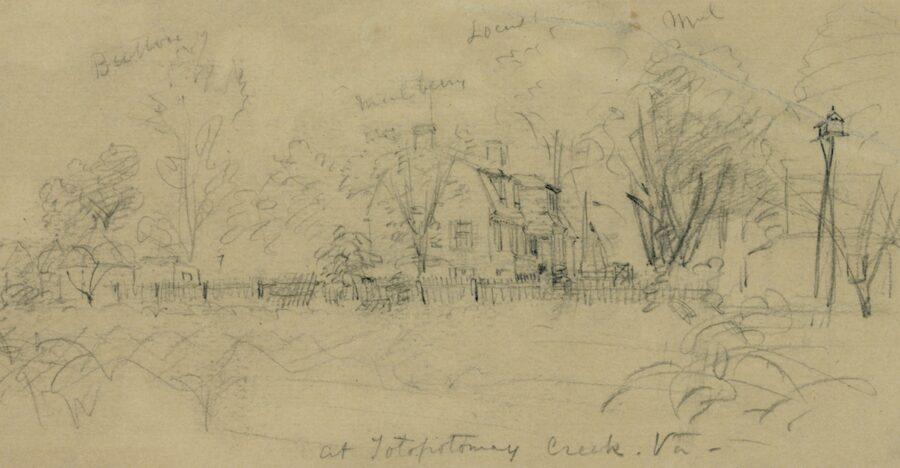

A few days later, the opposing armies left the North Anna behind and moved to the area northeast of Richmond. Lee took up a strong position behind Totopotomoy Creek. Both sides launched assaults on May 30, and while each attacking force produced some success, both lines held. This sketch by Alfred Waud shows General Winfield Scott Hancock’s temporary headquarters, the Shelton House, which was struck by more than 50 Confederate projectiles. The structure is now under the care of the National Park Service; the damage is still visible today.

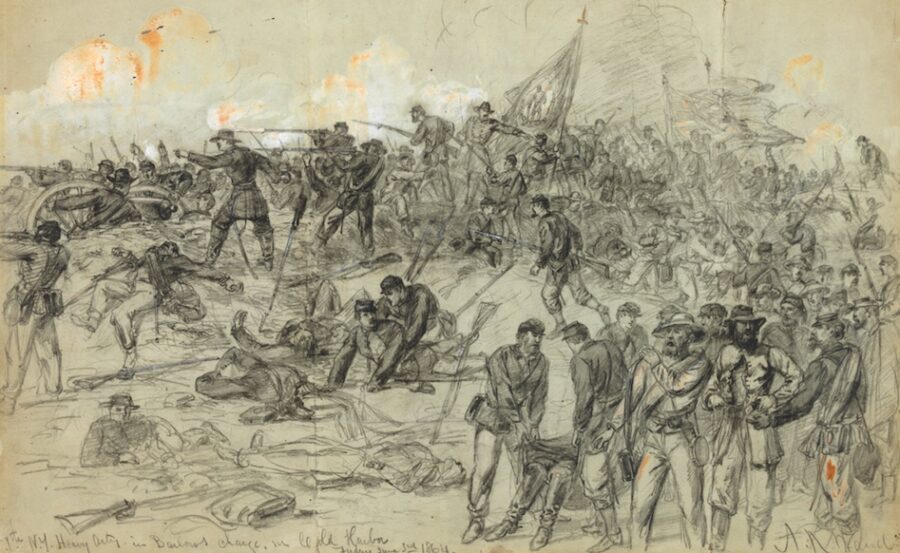

As he had done for the entire campaign, Grant continued to move by the left flank, which brought the armies back to the 1862 battlefield at Gaines’ Mill, near Cold Harbor. Fighting quickly erupted and climaxed with costly Union attacks on June 3. Here, Waud depicts heavy artillerymen of the Union II Corps during the bloody fight. The assaults at Cold Harbor gained Grant nothing.

At Cold Harbor, Confederates dug deep trenches and also felled trees, piled fence rails, and used anything else they could find to make their position impregnable. Days of withering rifle and artillery fire proved the quality of their work. By June 12, Grant’s only options were to launch likely futile attacks, retrograde toward Washington, or move by the left flank once again to cross the James River. The Overland Campaign had already cost the armies more than 75,000 casualties. Something needed to change.

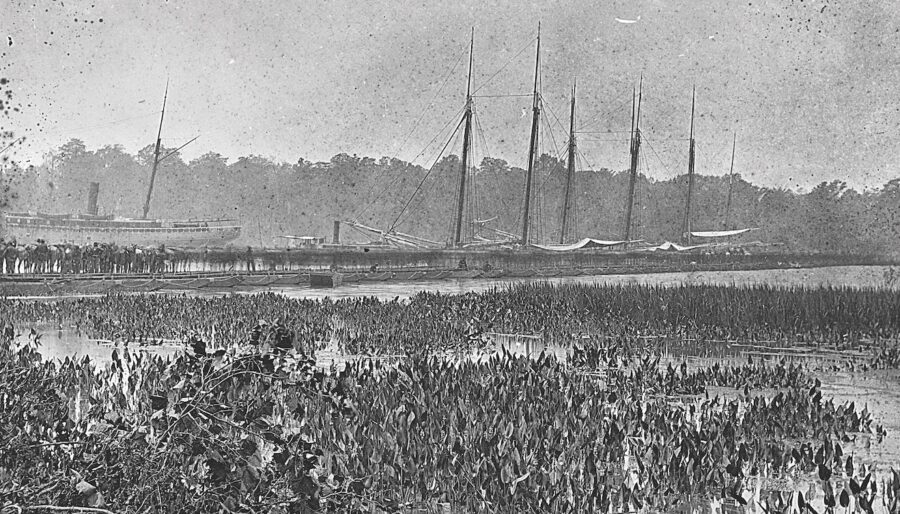

Grant’s decision to cross the James River and move southward toward Petersburg—a key rail center 20 miles south of Richmond—effectively ended the Overland Campaign. Lee was still unsure of Grant’s intentions even as Union engineers accomplished the incredible feat of constructing a 2,000-foot pontoon bridge over the wide waterway. Here, the bridge is crammed with Union soldiers marching toward an unknown fate.

Grant’s troops had stolen a march on Robert E. Lee. For three days, they enjoyed overwhelming numerical superiority over a small Confederate force under General P.G.T. Beauregard. The Confederates were well entrenched, however, in the works shown here, and gave ground slowly under large but overly cautious Union advances. By June 18, it was too late; Lee’s army had arrived and manned dozens of miles of fortifications protecting Richmond and Petersburg. A nearly 10-month siege of Petersburg would ensue—a result that neither side wanted. In April 1865, Grant’s forces would finally break Lee’s lines, an event that marked the beginning of the end of the Confederacy.