Reading Tom/Flickr

Reading Tom/FlickrThe house on First Street in New Orleans where former Confederate president Jefferson Davis died in 1899.

My “Unhidden History” series has a way of turning my trips into Civil War detective work; recently, the trail keeps looping back to New Orleans, of all places.

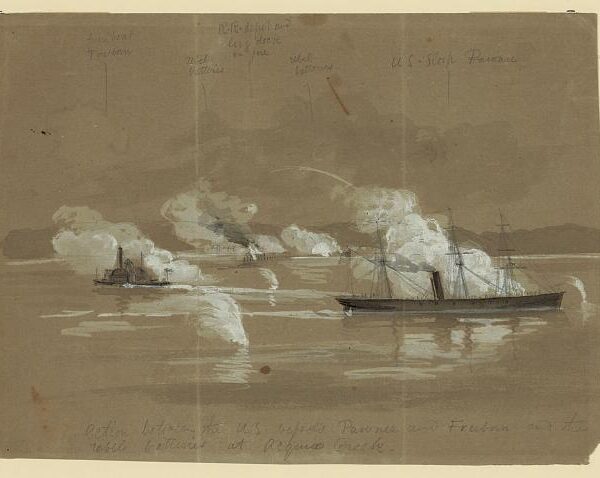

It started with a local history hunt near my home, where I learned of the grave of Confederate General Tyree Harris Bell in Sanger, California. That discovery sent me searching for the hospital where Bell died in New Orleans—I thought I had found it, but apparently not (another mystery for another day!). Then, while in New York City, I learned of Admiral David Farragut’s southern roots—a man whose loyalty to the country was stronger than to his home state, a man who then went and took New Orleans for the Union in 1862.

So, my trip to New Orleans connected me with Civil War history and my journey of unfolding hidden stories about it. While visiting the stirring Metairie Cemetery, which is packed with elaborate mausoleums and Confederate markers, my interest in the city’s history was piqued. The day itself was heavy—hot, humid, and quiet, with a thick layer of clouds and periodic breakthroughs of sunshine. Recent rain had left the paths muddy, and little pools of water on the raised tombs that reflected the sky and the stones made for an eerie and peaceful setting. It was in that stillness that I did a double take when I saw the burial place of Jefferson Davis.

Wait a minute. I’d been to Davis’ final resting place—his tomb in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. How could the former Confederate president’s remains be in two places?

This moment of confusion, sparked my curiosity and my quest for understanding why and when Davis was buried in New Orleans.

Who Was Jefferson Davis?

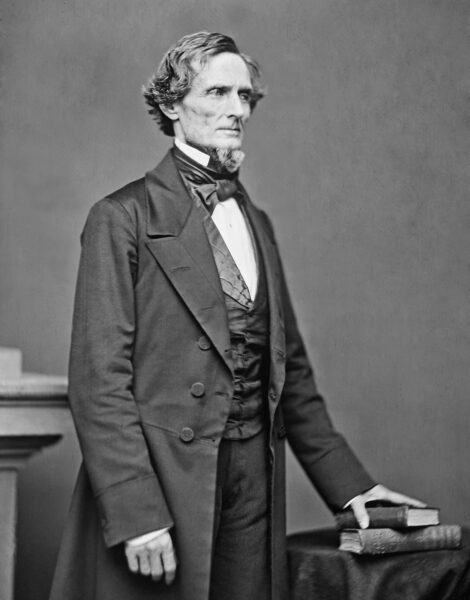

Library of Congress

Library of CongressJefferson Davis

Before getting into Davis’ final resting place, let’s talk about his life and Civil War service. Jefferson Davis (born in 1808 in Kentucky) was the first and only president of the Confederate States of America. That distinction is one that made him both vilified and revered.

He was a decorated veteran of the Mexican-American War, a well-known Mississippi cotton planter, a U.S. senator, and served as the U.S. Secretary of War before Mississippi’s secession from the Union. As Confederate president, he faced significant challenges of managing a new nation’s military, economy, and politics during wartime—his overall performance, in the eyes of many historians, leaving much to be desired. Following the Confederacy’s defeat, he was captured, accused of treason against the United States, and imprisoned for two years. Of his capture and captivity, Davis felt unjustly treated:

Men may be forgiven, who, actuated by prejudice, exhibit bitterness in the first hours of their triumph; but what excuse can be offered for one who in cold blood, deliberately organizes tortures to be inflicted, and superintends for over a year their application to the quivering form of an emaciated, exhausted, helpless prisoner, who, the whole South proudly remembers, though reduced to death’s door, unto the end neither recanted his faith, fawned upon his persecutor, nor pleaded for mercy.1

Released without trial in 1867, Davis spent the remainder of his life defending his wartime actions and the southern cause. As one historian said of Davis, “Even though the people of the South had grown critical of him in the waning days of the war, he became a martyr for their cause.”2 Davis’ post-captivity popularity grew; he was greeted by large crowds whenever he traveled in the South, and his funeral procession in New Orleans drew an estimated 200,000 people.

A Four-Year Stopover

My quest to figure out the two-cemetery mystery led me to Mark Bielski, a knowledgeable and engaging New Orleans historian and tour guide. Mark explained that Davis, while traveling in late 1889, had fallen seriously ill with malaria and bronchitis and was forced to stop in the city. He was taken into the Payne-Strachan House (a classic Greek Revival mansion) on First Street in the Garden District, the home of his friend, Judge Charles Fenner. (Fenner is infamous in his own right for contributing to the Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which created the doctrine of “separate but equal” accommodations for whites and non-whites.) Davis passed away there on December 6, 1889.

Zethyn McKinley

Zethyn McKinleyThe Tomb of the Army of Northern Virginia monument in New Orleans’ Metairie Cemetery, where Jefferson Davis was initially buried.

New Orleans wasn’t Davis’ home, but rather an unfortunate and unexpected stop on a journey. And because his wife, Varina, had a large, politically charged task ahead of her—choosing a permanent resting place for him that would satisfy the entire postwar South—Davis’ body was initially interred in New Orleans, specifically in the Army of Northern Virginia tomb in Metairie Cemetery.

Davis remained in that tomb for four years while Varina organized the logistics of his final burial. In May 1893, his remains were moved to Richmond. Mystery solved, history illuminated.

Though many (especially southern) Civil War enthusiasts may already have known this fact, learning it wasn’t the final piece for me, or this story.

The Quiet Act of Historical Erasure

During our conversation, Mark delivered the historical kicker that truly brought the “unhidden history” theme home: That house on First Street, a gorgeous but otherwise unassuming private residence, once had markers detailing its significance as Davis’ death location.

But that plaque is gone.

Mark explained that the marker and a related stone monument were quietly removed and covered over, respectively, in 2020 during the highly charged controversy over the removal of the city’s Confederate monuments. It was an act of historical sanitization done out of an abundance of caution—mostly to spare the private residents the headache of controversy or unwanted attention.

However understandable the desire for privacy might have been, this erasure is a modern example of keeping unwanted or otherwise uncomfortable history hidden. Whatever the reason, a small yet significant piece of the city’s past was wiped away. If I hadn’t seen the temporary burial marker in Metairie Cemetery, I never would have known the story of an otherwise ordinary house on First Street.

It’s a roundabout, yet profound, reminder that history isn’t just about what’s preserved and celebrated; it’s also about what’s taken down, painted over, or simply forgotten. And sometimes, it takes a random double-take in a cemetery to bring that hidden history back to the surface. Of course, such changes can also rightfully be seen as symbols of progress, of a city consciously deciding to move on. Though it does, in my mind, beg some fundamental questions: Does every scuff on a historical wall need to be preserved? Or is deliberate erasure necessary for healing, growth, and making space for future stories and experiences?

One thing I’m sure about: New Orleans has weaved together many complicated stories linked together by one war, and I am she sure has many more to tell. Some of which, perhaps, we will explore in future installments of “Unhidden History.”

Zethyn McKinley is a freelance writer and editor with an interest in history, technology, and politics. Beyond her research and writing, she is a certified yoga teacher and blogger at 360 Yoga, where she shares insights on finding physical and mental balance. She resides in California’s Central Valley.

Notes

1. Varina Davis, Jefferson Davis, Ex-President of the Confederate States of America: A Memoir, by His Wife (New York, 1890), 2: 643.

2. Mark Beilski, A Mortal Blow to the Confederacy: The Fall of New Orleans, 1862 (2021), 168.

Related topics: Jefferson Davis