Philip Pane/The Gettysburg Compiler

Philip Pane/The Gettysburg CompilerA modern-day view of part of the Harmon Farm lands on Willoughby’s Run.

In 1863, on the edge of town in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, beyond the Lutheran Theological Seminary and along the west bank of Willoughby’s Run, lay the Harmon Farm. Emanuel Harmon, born in Adams County, Pennsylvania, in about 1818, had purchased the 124-acre farm in 1857. The farm’s northern boundary was Chambersburg Pike, and its southern boundary Mill Road, today’s Old Mill Road. Harmon lived in Washington, D.C., where he had received five patents: three involving improvements in envelopes and postage and one involving a “fireproof iron building.”

In July 1863, several members of the Harmon family occupied the farm, including Amelia Harmon, 16, her aunt Rachel Harmon and Rachel’s husband, David Finefrock. So too did William Comfort, a tenant farmer like Finefrock. The farm (all but 22 of its 124 acres under cultivation) had fields of wheat and rye and a potato patch, as well as at least five sheep and 11 cattle. A large, impressive brick house, a stone barn, a two-story brick washhouse, a smokehouse, and a corncrib also stood on the property. In short, the Harmon Farm was thriving, productive, and peaceful—until, on the afternoon of July 1, Union and Confederate soldiers descended on Gettysburg and battled for control of Emanuel Harmon’s land and buildings.

The deadly contest began in the early afternoon as Confederate soldiers of Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew’s North Carolina Brigade occupied the Harmon Farm buildings, using them as cover for sharpshooters. The riflemen particularly targeted the recently arrived troops of a Union brigade (consisting of the 80th New York and the 121st, 142nd, and 151st Pennsylvania infantry regiments) and the Third Division, I Corps, commanded by Colonel Chapman Biddle. The Carolinians began to fire on the Pennsylvania and New York infantrymen and some Union artillerists under Captain James Cooper on East McPherson Ridge. Private Enos Vail of the 80th New York recalled: “[W]e were greatly annoyed by a company of sharpshooters who had taken possession of a house in front of us and were killing and wounding many of our men. Their fire was very destructive among the gunners of Cooper’s Battery…. The gunners were picked off so fast that some of our men had to assist them to work the guns.”

Brigadier General James Wadsworth, commander of the Third Division, soon ordered Colonel Theodore Gates of the 80th to take the Harmon house. Gates dispatched the 38 soldiers of Company K under the command of Captain Ambrose Baldwin, who advanced his men across the open terrain from McPherson’s Ridge under enemy fire from cannon shells and small arms. They crossed Willoughby’s Run and “drove the enemy from the buildings and took possession of them.” Amelia Harmon, who elected to remain in the house with her aunt, recalled “a sudden, violent commotion and uproar below made us in quick haste to the lower floor. There was a tumultuous pounding with fists on the kitchen door”; when the women unbolted it, “a stream of maddened, powder-blackened Ulster Guard soldiers came in.” Amelia and her aunt were ordered to the basement.

The fighting intensified as Company K’s advanced position became the focal point of Confederate fire. Baldwin ordered his second in command, Lieutenant John M. Young, to find Gates and request reinforcements. Young’s report—“Colonel, its damned hot out there”—prompted Gates to dispatch the 34 men of Company G, under the command of Captain William Cunningham, to Baldwin’s aid. The reinforced New Yorkers began making trouble for the surrounding Confederates. Colonel Keith Marshall of the 52nd North Carolina noted destructive Union fire coming from the second story of the Harmon house; another Rebel soldier added, “the enemy sharpshooters reminded us that we had better cling close to the bosom of old mother earth.”

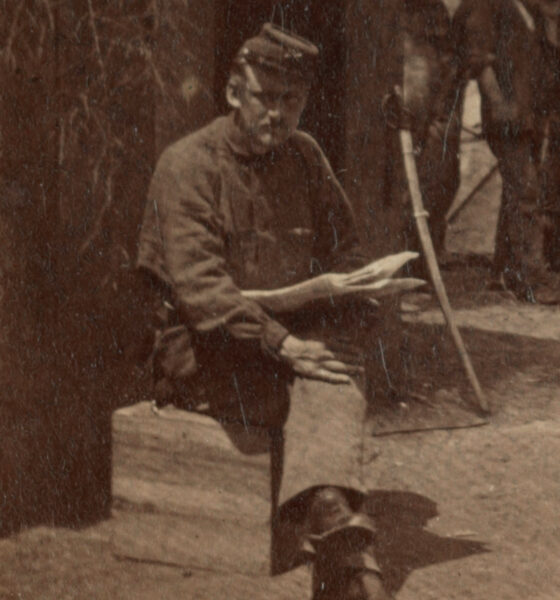

North Carolina Museum of History

North Carolina Museum of HistoryBrigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew, whose North Carolina Brigade battled Union soldiers for the Harmon Farm on July 1, 1863.

Around 2:30 p.m., the balance of the North Carolina Brigade came forward from Herr’s Ridge and advanced on the Harmon Farm. Captains Baldwin and Cunningham watched in awe and horror as the 52nd North Carolina, 553 men strong, slowly approached. The Union position became untenable. Baldwin and Cunningham, not wishing to be captured, fled with their companies. Amelia, who was still in the basement, later noted: “Of a sudden there came a scurrying of quick feet, a loud clattering on the staircase above, a slamming of doors and then for an instant silence…. Next act in the drama … the sound and the shadow of hundreds of marching feet. We can see them to the knees only, but the uniforms are Confederate gray. Now we understand the scurrying feet overhead. Our soldiers have been driven back, have retreated, left the house, and left us to our fate.”

As the New Yorkers withdrew, Colonel Marshall was determined to prevent any further enemy use of the Harmon Farm buildings. He ordered his men to burn the house and barn. Captain Benjamin Little of the 47th’s Company E recalled, “The … house was burned by order of Col. Marshall because of the sharpshooters firing upon us. The men burned it very reluctantly, but it was the only way we could get them out. We had no artillery. Burnt it as we were making the advance.”

As some of Marshall’s men entered the house to set fire to it, they were confronted by Amelia Harmon and her aunt. Amelia recalled: “We rushed up the cellar steps to the kitchen. The barn was in flames … the house was filled with Rebels, and they were deliberately firing it. They had taken down a file of newspapers for kindling, piled on books, rugs, and furniture, applied matches to ignite the pile, and already a tiny flame was curling upward. We both jumped on the fire in the hope of extinguishing it and plead with them to spare our home. But there was no pity in those determined faces.”

Amelia and her aunt fled the burning house with only the clothes they wore, hurrying west through the Confederate lines. Amelia later wrote of the experience, “We fled from our burning home only to encounter worse horrors. To go toward town would be to walk into the jaws of death. Only one way was open-through the ranks of the whole Confederate army to safety in its rear.”

After the battle concluded, the Harmons could visit what was left of their home. Amelia later wrote, “When we reached the site of our home, a prosperous farmhouse five-days before, there appeared only a blackened ruin and the silence of death.”

Emanuel Harmon did not rebuild the house and barn; instead he purchased land elsewhere in town, where Rachel Harmon and David Finefrock resided for some years. After the war, Amelia Harmon met George Miller, a local resident whom she married in 1868. The couple had four children. Miller’s position as a Methodist minister required frequent moves throughout the Mid-Atlantic states; when he retired in 1910, he and Amelia relocated to Asbury Park, New Jersey. Amelia was nearly 70 when she wrote an account of the burning of Harmon Farm; it was published in a 1915 issue of the Gettysburg Compiler. She probably died sometime before the 1920 census, where her name is not listed.

Larry Korczyk has been a licensed battlefield guide at Gettysburg National Military Park for 13 years. He has conducted hundreds of tours on the battlefield (with a specific focus on the leadership of army commanders George Meade and Robert E. Lee), is a regular speaker at Civil War round tables, and is co-author of the book Top Ten at Gettysburg (2017).

Related topics: women