Library of Congress

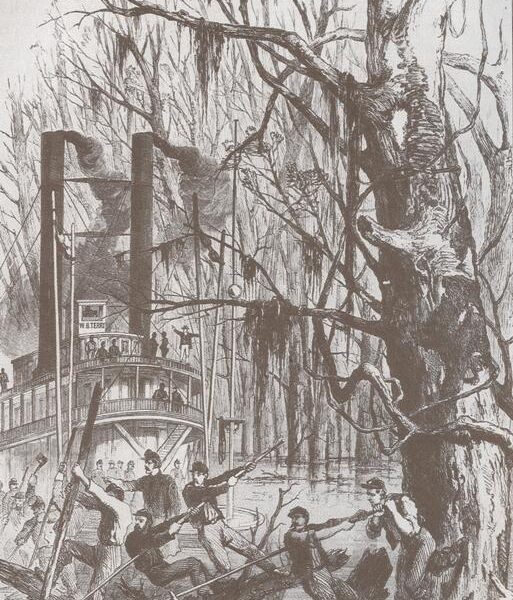

Library of CongressAlexander Gardner’s photograph of the Sunken Lane at Antietam documents one portion of the battlefield where the bodies were packed densely enough that you could walk across the road without touching the ground.

What do the Wheatfield at Gettysburg, the Cornfield at Antietam, and the grass fields below Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg have in common? Each of them covered about 25 acres, and each was the site of identical unusual events we have read about in many a history book. The first occurrence is that during the battle bullets flew with the intensity of hail in a great storm. The second occurrence describes the aftermath of that leaden precipitation: The entirety of the field was so covered in dead bodies that a person could walk across it from one side to the other, in any direction, without ever setting foot on the ground.

These vivid, intense, and grisly descriptions seem plausible—it’s in a history book, after all! Hailstorms of bullets (and artillery shells) and carpets of corpses are not only recounted by the soldiers and eyewitnesses who observed them, they are often repeated by historians as fact.1 A critical analysis of these accounts from a scientific perspective, however, proves they are not just implausible. They are preposterous.

Let’s start with a brief discussion of the science involved in both scenarios. First, bullets falling with the intensity of frozen precipitation. In hailstorms, the icy spheres form from water droplets being elevated and freezing, where they begin to descend, adding more water, before ascending and freezing again, repeatedly. The stronger the updrafts, the larger the hailstones. This also produces an inverse relationship between hailstone size and frequency of occurrence: Hail the size of a pistol bullet will fall with a density twice that of stones the size of a minie ball, and stones the size of grapeshot will have strikes that are on average about twice as far apart as rifle rounds. If you happen to be standing in a strong hailstorm, you might see hailstones the size of a .58-caliber bullet falling with the intensity of about five strikes per square foot per minute, and this may take place for more than five minutes. When all the data is amalgamated, in a typical hailstorm you can expect to see around 10 pistol-bullet-to-grapeshot-size hailstones falling per square foot per minute.

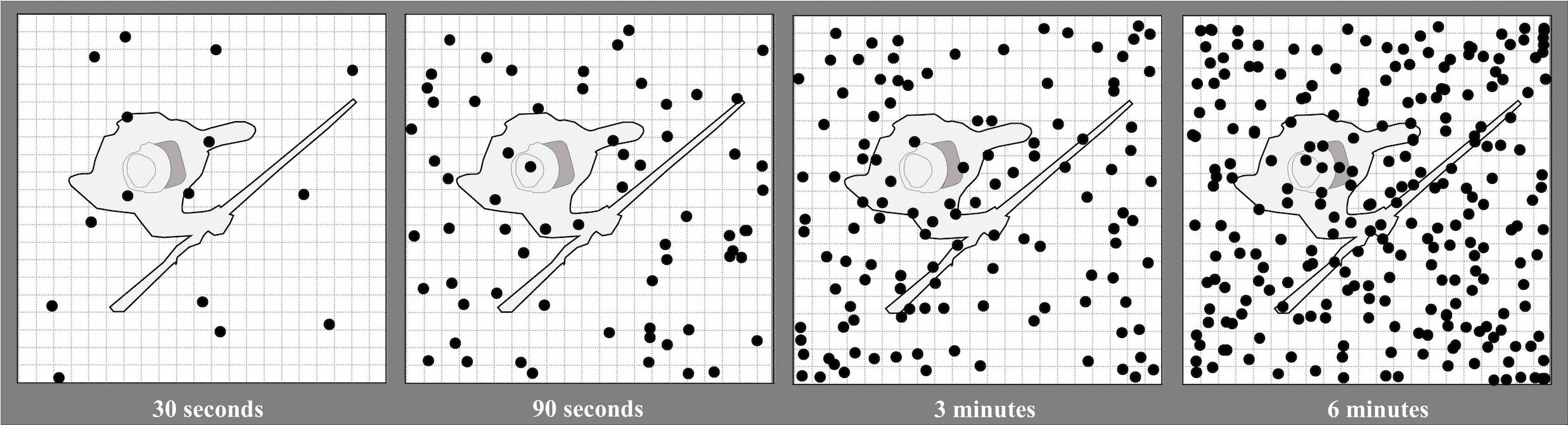

Scott Hippensteel

Scott HippensteelRandomly generated hailstone impact sites superimposed on an overhead outline of a Civil War soldier carrying a rifle. Within 30 seconds, a soldier would be struck three or four times, and in any storm (or firefight with leaden hail) that lasted more than two minutes, the infantryman would be hit at least a half dozen times.

With bullets flying like hailstones, how long could a soldier expect to live before being struck?

The average surface area of a Civil War soldier is around 20 square feet. Of course, when hail strikes a person, it usually comes from one direction (from above, or with high winds, from above and at an angle). This reduces the surface area of the unlucky combatant to half the 20 square feet, and if he is standing vertically, only a few square feet are vulnerable to being hit.2 Even so, in a typical hailstorm a soldier should expect to be hit with around 20 stones (bullets) per minute. In a five-minute firefight with this intensity of hail strikes, a soldier might be hit more than 100 times. With lead precipitating at this rate, the soldier would be fortunate to live to write about his experience.

The density of dead bodies in that other popular tale is even easier to dismiss with critical analysis. The smaller the surface area of the field in question, the more realistic the claim that it could be covered so completely with the dead that one could traverse it walking entirely on corpses. Antietam’s Miller Cornfield and Gettysburg’s Rose Wheatfield are among the literature’s most cited examples of such a gruesome carpet, and both cover a similar tract of about 20 acres. To walk across it stepping only from body to body would require the bodies to be close enough so that the strides between steps wouldn’t be more than a few feet—the tale states that one could “walk,” not jump, across the field. Given a single dead soldier covering an area about 5½ feet high and a few feet across, this would represent a patch of about 20 feet squared. Add into the calculation the small area between bodies that a person could step over without jumping (a foot or so surrounding and on either side of the adjacent dead bodies), and we reckon that each corpse can cover an area of about 40–50 square feet. Note that all of these spatial estimates err on the side of covering too much ground—they favor the tale being true.

So to cover the Wheatfield or Cornfield, we need enough dead soldiers to blanket 20 to 25 acres—almost a million square feet! With more precise estimates of the surface area of the Cornfield, we find that 22,250 dead bodies would be needed to produce a carpet of death that “a person could walk across in any direction without ever touching the ground.” About 4,000 men died at Antietam; if you dragged all the dead from all sectors of the battlefield, you would be able to cover only about one-fifth of the Cornfield.

At Gettysburg, 16,500 bodies would be needed to cover the Wheatfield. If you gathered all the dead from the three days of fighting, you couldn’t cover even half of that field. When similar spatial-lateral analysis is reconsidered for these relatively small fields, it makes similar claims for the ground below Marye’s Heights or the farm fields of Pickett’s Charge appear even more absurd.3

Scott Hippensteel

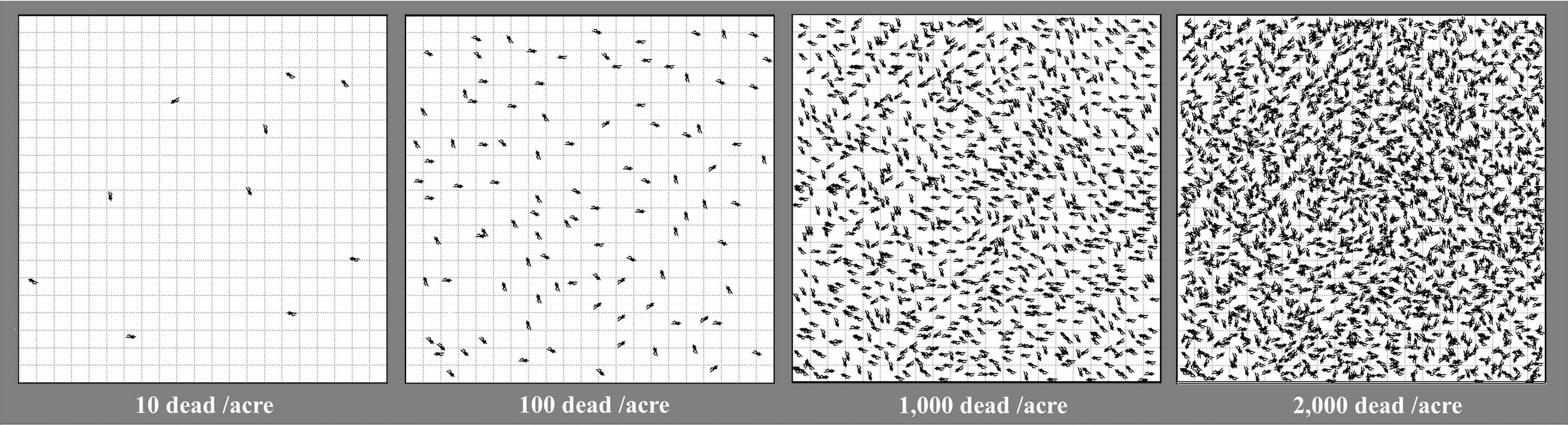

Scott HippensteelIncreasing density of dead across one square acre of battlefield land. The most probable scenario for the distribution of corpses at the Cornfield at Antietam or the Wheatfield at Gettysburg would have been around 100 dead (or far fewer) per acre, demonstrating the “carpet of death” scenario as improbable. Even at 2,000 dead per acre—a density so great it would require five times the number of killed in action from the entire battle—there are still open portions of the field that would be difficult to cross without stepping on the ground.

So how did these tales originate? I suspect for the “bullets falling with the intensity of hail” the answer is simple: Civil War soldiers had difficulty describing to others the shocking intensity of combat. What other small, fast objects speed through the air that would be comparable for use in a description? (Many accounts of bullets flying through the air like a swarm of bees can also be found.) Soldiers using the hailstorm comparison understood that this description was not to be taken as fact, but that is what has occurred after repeated retelling in lectures and history books.

For the carpet of death story, I point to the Antietam battleground as a likely scenario for how the exaggeration originated and became embedded in wartime storytelling. There is one portion of that area that certainly could have contained a swath of bodies so densely packed that you could walk across it without touching the ground: the Sunken Road. Based on Alexander Gardner’s photographic evidence, it is clear that you could walk across this road without touching the ground. Claims that you could walk the length of the road without touching soil, which assertations do exist, are more improbable. Perhaps the eyewitnesses to the fighting for the Bloody Lane later shifted their memory of this density of death to the Cornfield, less than a mile away. For those who survived the terrible experience of combat that occurred at both locations, this feels forgivable. What is not is the frustrating habit of authors and commentators of repeating these claims, over and over through time, as if they were factual. Our best historians consistently include these descriptions of hailstone strikes and carpets of death, but with a note of caution. James M. McPherson, the eminent Civil War historian, will often note in his writing that an unrealistic quote chosen for inclusion was created “doubtless with some exaggeration.” This skillfully allows the author to pass along the narrative of the terrified or horrified eyewitness, while at the same time recognizing the embellishment provoked by the trauma of the event.

Scott Hippensteel is professor of Earth sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he focuses on coastal geology, geoarchaeology, and environmental micropaleontology. He has written four books about using science to illuminate military history: Sand, Science, and the Civil War: Sedimentary Geology and Combat (University of Georgia Press, 2023), Myths of the Civil War: The Fact, Fiction, and Science behind the Civil War’s Most-Told Stories (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), and Rocks and Rifles: The Influence of Geology on Combat and Tactics during the American Civil War (Springer Nature, 2018). His latest book, Civil War Photo Forensics: Investigating Battlefield Photographs through a Critical Lens, is forthcoming from the University of Tennessee Press.

Notes

1. The “bullets flying with the intensity of hail” description can be found in history books about Gettysburg, First Manassas, Shiloh, Second Manassas, Antietam, Malvern Hill, Ball’s Bluff, Chancellorsville, South Mountain, Fredericksburg, Stones River, Atlanta, and Port Hudson. The “carpet of corpses” is found in books and articles about Antietam, Gettysburg, Perryville, Fredericksburg, Shiloh, Pickett’s Mill, Nashville, Franklin, Tupelo, Second Manassas, and Petersburg.

2. Standing vertically when the incoming hail (or gunfire) is coming from above makes a strike to the head or shoulders much more likely, increasing the probability of a casualty becoming a fatality.

3. If all the combat dead from the entire war were brought to Gettysburg, they still would not begin to cover the fields traversed by the Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Assault. At Fredericksburg, multiple authors claim a carpet of death extended for one-half or even three-quarters of a mile, with one article in American Heritage stating that a person could have walked from the “river to the heights” without ever touching the ground. That distance is nearly a mile.