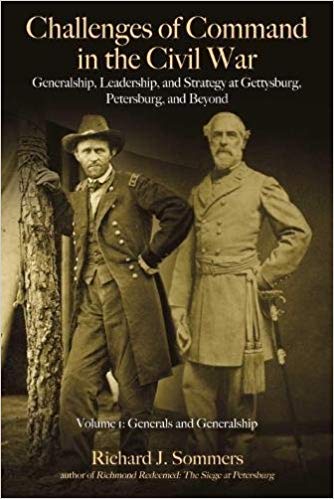

Challenges of Command in the Civil War: Generalship, Leadership, and Strategy at Gettysburg, Petersburg, and Beyond by Richard J. Sommers. Savas Beatie, 2018. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1611214321. $29.95

Every serious student of the Civil War knows Dr. Richard J. Sommers for his four decades of service as the Senior Historian of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and for his unsurpassed campaign study, Richmond Redeemed, chronicling Grant’s fifth offensive during the Union’s 292-day investment of Petersburg, Virginia. Over the years, however, Dr. Sommers has also adddressed smaller audiences at numerous Civil War symposiums and roundtable meetings around the country. Now, thanks to Savas Beatie, many of these commentaries are being updated, preserved in print, and made available to a broader audience.

Every serious student of the Civil War knows Dr. Richard J. Sommers for his four decades of service as the Senior Historian of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and for his unsurpassed campaign study, Richmond Redeemed, chronicling Grant’s fifth offensive during the Union’s 292-day investment of Petersburg, Virginia. Over the years, however, Dr. Sommers has also adddressed smaller audiences at numerous Civil War symposiums and roundtable meetings around the country. Now, thanks to Savas Beatie, many of these commentaries are being updated, preserved in print, and made available to a broader audience.

In the first of two projected volumes, Dr. Sommers devotes five chapters to the generalship of the war’s two premier antagonists, Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant. An additional four chapters examine the abilities and limitations of the Army of the Potomac’s senior corps commanders. A concluding chapter chronicles some of the Revolutionary War relatives of significant Civil War soldiers and statesmen. While none of the essays represent new scholarship, each reflects Dr. Sommers’ ongoing analysis of personalities who have been the focus of his professional life. For readers unfamiliar with Dr. Sommers, this volume serves as welcome introduction to the work of a distinguished historian. For those who already know and admire Dr. Sommers, these essays provide context to a life devoted to Civil War historiography.

Sommers compiles thirteen hallmarks of Grant’s generalship that can be included under a basic framework Grant himself defined: “The art of war is simple enough; find out where your enemy is, get at him as soon as you can; strike him as hard as you can, and keep moving on.” Nevertheless, Sommers finds some chinks in Grant’s usually impenetrable armor. “His judgment of subordinates and staff officers,” Sommers concludes, “was mixed,” and his confidence in ultimate success “occasionally caused him to overlook opportunities.” Not surprisingly, however, Sommers attributes the ultimate success of the Union armies to Grant’s theory and method of waging war.

Analyzing Grant’s generalship during the Virginia Campaign of 1864-1865, Sommers describes how he succeeded “because of his perseverance, his resourcefulness, and—particularly—his ability to learn from experience and adapt accordingly.” The Army of the Potomac’s eight offenses against Petersburg—the key to Richmond and success in the war in the east—offer outstanding examples of Grant’s fixity of purpose and flexibility of methods, and his ability to learn from his mistakes and later turn them to his advantage. In the end, Sommers concludes, Grant “secured success through a succession of setbacks.”

Sommers’ analysis of Robert E. Lee’s generalship is more critical. While he admires Lee’s tactical brilliance and audacity in the face of seemingly daunting odds, Sommers concludes that the loss of the strategic initiative denied Lee one of his most successful tactics: the counterattack. At Petersburg, “his counterattacks rarely produced spectacular victories that drove the Unionists from the field. More often, his counterattacks succeeded only in slowing the Federal juggernaut and stopping it short of its objective—but not in hurling it back.” Lee’s persistence in fighting as he had always fought, Sommers opines, “incurred needless casualties, reduced the disparity of losses between the two sides, diminished the Southern sense of success, and gave the Yankees something about which to cheer.” In the end, Lee’s counterattacking style only temporarily offset his numerical weakness. Grant, however, “learned from experience and matured his approaches to warfare.”

In the book’s second section, Sommers offers thumbnail commentary on the abilities and deficiencies of the Union’s second tier of commanders, both civilian and regular army. While General Lee makes at least a cameo appearance in the book’s first section, Dr. Sommers chooses to examine only soldiers wearing blue in the second. Perhaps limitations of space (and time during his original presentations) forced this truncated approach. Nevertheless, in a single sentence, Dr. Sommers often conveys more information and insight than might an entire paragraph in the hands of other commentators.

Dr. Sommers offers observations on twenty citizen-soldiers and starts with eight who served as corps commanders in Grant’s Army of the Tennessee. Among them were John A. McClernand, Grant’s “insubordinate subordinate,” who never commanded an army he thought he warranted. Stephen A. Hurlbut had the misfortune of trying, and failing, to catch Nathan Bedford Forrest. Cadwallader Washburn’s greatest success was his post-war founding of the company that is now General Mills. Grenville Dodge organized Grant’s successful spy network, but his chief claim-to-fame was as the Chief Engineer who completed Union Pacific portion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. John A. Logan’s fighting abilities earned him his stars during the war and leadership of the Grand Army of the Republic afterwards. Benjamin H. Grierson, the prewar piano teacher who didn’t like horses, became a first-rate cavalry commander, led the successful diversionary raid through Mississippi and Louisiana preceding the Vicksburg Campaign, and stayed in the army after the war to command the all-black 10th U.S. Cavalry in the West for almost twenty-five years.

Dr. Sommers is able to more thoroughly expostulate on individual capabilities when he has fewer personalities to examine. His analysis of George McClellan’s corps commanders during the Antietam Campaign, George G. Meade’s subordinates during the Gettysburg Campaign, and Grant’s “main men” during the Fifth Offensive at Petersburg are both interesting and informative. A reader can almost hear Dr. Sommers’ pedagogical voice as he reels off his “last words” on Grant’s subordinates: “Crawford and DeTrobriand, unknowable; Butler and Kautz, marginal; Heckman, incompetent; Birney and Weitzel, uncertain; Parke and Terry, unfulfilled; Warren and Ord, good but flawed; Hancock, good but inactive; Meade and Gregg, sound and competent; and Grant, outstanding.”

In his final chapter, Dr. Sommers “highlights a few of the family connections that united the ‘Greatest Generation’ of the 18th and 19th Centuries—the generation that gained American independence and the generation that either preserved the American nation or else fought for Confederate independence.” Limiting his examination to “acclaimed ancestors of distinguished descendants,” Dr. Sommers identifies fifty-nine Founding Fathers related to ninety-one Civil War warriors. It’s a fascinating conclusion to an altogether satisfying volume.

Gordon Berg has penned articles for numerous Civil War publications. He writes from Maryland.