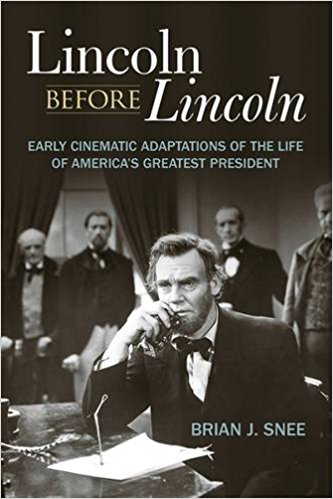

Lincoln Before Lincoln: Early Cinematic Adaptions of the Life of America’s Greatest President by Brian J. Snee. University Press of Kentucky, 2016. Cloth, ISBN: 978-0-8131-6747-3. $40.00.

Abraham Lincoln surely holds the record for presidential movie roles, having been inserted into more than 200 movies, television programs, and documentaries. The cinematic Lincoln made his debut in 1903 at the end of a ten-minute Edison version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and has strolled onscreen in every other imaginable venue from Star Trek and The Twilight Zone to National Treasure 2. Sooner or later, the filmed Lincoln was going to yield the film-critic Lincoln, and Brian Snee (whose earlier books were focused on Michael Moore and political documentaries) now joins Mark Reinhart’s Abraham Lincoln on Screen: Fictional and Documentary Portrayals on Film and Television (1998) and Frank Thompson’s Abraham Lincoln: Twentieth-Century Popular Portrayals (1999) as book-length appraisals of Lincoln in celluloid.

Abraham Lincoln surely holds the record for presidential movie roles, having been inserted into more than 200 movies, television programs, and documentaries. The cinematic Lincoln made his debut in 1903 at the end of a ten-minute Edison version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and has strolled onscreen in every other imaginable venue from Star Trek and The Twilight Zone to National Treasure 2. Sooner or later, the filmed Lincoln was going to yield the film-critic Lincoln, and Brian Snee (whose earlier books were focused on Michael Moore and political documentaries) now joins Mark Reinhart’s Abraham Lincoln on Screen: Fictional and Documentary Portrayals on Film and Television (1998) and Frank Thompson’s Abraham Lincoln: Twentieth-Century Popular Portrayals (1999) as book-length appraisals of Lincoln in celluloid.

Rinehart’s pioneering volume was more of an annotated catalog than an essay in criticism; Thompson treated the movies’ Lincoln thematically, examining silent Lincolns, television Lincolns, comedy Lincolns, and actors (especially Ralph Ince) who made careers out of playing Lincoln. Snee is a cultural analyst, for whom film and television are the real subject and Lincoln merely an opportunity to examine how “media, film and television are recognized as perhaps the most persuasive” of all visual media, “the archetypes of the new technologies of memory created in the twentieth century.” And rather than attempting any comprehensive survey, Snee’s seven brief chapters concentrate one-by-one on D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), his 1930 biopic, Abraham Lincoln, John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), Robert Sherwood’s Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940), and two made-for-television series, Sandburg’s Lincoln (1974-76) and Gore Vidal’s Lincoln (1988).

Snee’s book arrives at an interesting moment. Lincoln’s popular historical standing peaked in the 1940s, and the slow ebb that followed could be measured by how Lincoln descended from a figure of reverence in Ford and Sherwood to the buffoon-figure in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989). The bottom of the barrel seemed to have been reached in 2012, with Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter – except that 2012 also saw the release of Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, a serious and heroic recovery of a heroically serious Lincoln. After the deflated observances of the Lincoln bicentennial in 2009, Spielberg’s Lincoln came as a reversal of historical memory, and posed a perplexing question for those who assumed that both memory and history only ever proceed in one direction.

Why film should be so important a marker of historical memory is a question of its own. Snee deploys a forbidding array of critical theorists—Maurice Halbwachs, John Bodnar, Gary Edgerton—to define “public memory” as (in Bodnar’s words) “a body of beliefs and ideas about the past that help a public or society understand its past.” Underlying Bodnar’s (and Snee’s) premise, however, is the critical contention that historical understanding is nothing but memory—that there is no real access to fact, no assertion unalloyed with the seamier desire to exercise power and control after the bleak pattern of Orwell’s “memory hole.” The patient work of historical reading, research, and review comes to be regarded as only one means by which memory is shaped; in the end, that too is treated merely as an imposition, confected in the interests of power, masquerading as truth. If film really is “the most persuasive” tool for creating “public memory,” then the role of film in remembering Lincoln must surely be as significant as any biography, no matter how meticulous the biography may be in its research, inquiry and presentation.

Except, of course, that film isn’t, and can’t be. Any history film is necessarily an essay in fiction. A book, say, on the Gettysburg Address need only focus on the Address and what the accumulated evidence tells us about it; a movie about the Gettysburg Address must invent details which no one can determine with any certainty (how Lincoln tied his cravat, the color of his horse’s mane) to keep the story moving as a visual story. In fact, the sheer volume of detail a film must invent dwarfs whatever truth it contains. In the need to maintain the story, truth itself must be a negotiable quantity. History-writing can be wrong-headed, mistaken, and when badly-done almost fictional; but that is what we condemn as bad history. A history film that tries to take flight from fiction will be a bad movie, not to mention a very, very short one. Film may indeed shape public memory more readily than history-writing, but we have no reason to applaud that unless we believe that individuals and societies can live by constant diets of falsehood. Film is an entertainment; if it succeeds in the business of memory, it is only by insinuation. But it is a powerful insinuation, and that is why its shaping power is something to deplore, not concede uncritically.

That Snee’s grasp of Lincoln biography is a loose one is, on those terms, not a surprise, and his blunders on that score are numerous to the point of embarrassing. For instance: Spielberg’s Lincoln was not based on “an award-winning biography penned by a Harvard historian,” but on Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals (which is not a biography, nor is Goodwin a Harvard historian). The Ann Rutledge romance is not a “historically suspect relationship,” unless everything written subsequent to John Y. Simon’s and Douglas Wilson’s essays on Rutledge and Lincoln in 1990 are to be ignored. The details of the Beardstown “almanac trial” are not “the subject of continual debate among historians,” something easily discoverable in John Evangelist Walsh’s Moonlight: Abraham Lincoln and the Almanac Trial (2000). The Day Lincoln Was Shot was not “a 1955 novel by Jim Bishop,” even if Bishop tended to take some testimony about the Lincoln assassination a little too unreflectively. And is it not time to dismiss once and for all the notion that Lincoln’s “legendary address at Gettysburg” was “initially judged a failure”?

This looseness may not be unconnected with the accolades Snee bestows on John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln, which Snee asserts was as influential as Ford’s contemporary Carl Sandburg’s The Prairie Years and The War Years in shaping “twentieth-century America’s sense of Lincoln.” Ford was a disciple of the great Soviet film-maker, Sergei Eisenstein, who encouraged writers and directors to abandon simple narrative in favor of incorporating a dialectical movement into movies. Thus, Ford’s Young Man Lincoln magically reconciles opposites: natural law and human law in a trial modeled on the Beardstown trial, episodes as disparate as a pie-judging contest and political debate, physical force and theatrical force. That Ford threw the historical record to the winds, mashing-together events and personalities, scarcely mattered. The dialectical method “would transform mere movies into potent sites for serious social and political commentary.”

By contrast, Snee is dismissive of the six-part television series Sandburg’s Lincoln, despite the fact that Hal Holbrook worked with unusual diligence to re-create the peculiar high-pitched nasal twang of Lincoln’s voice, and the late Sada Thompson turned-in one of the most sympathetic and straightforward versions of Mary Lincoln on any screen. No matter: Sandburg’s Lincoln is panned as “an overly sentimental text that acted as a kind of anti-activist antidote for mid-1970s television audiences, weary after a decade of protest and upheaval.” Holbrook’s portrayal “privileges emotion over reason” and indulges in a “whitewashing of the historical record.” Granted, that producer David Wolper (who had produced a Lincoln assassination documentary, They’ve Killed President Lincoln, in 1971, and went on to produce Roots in 1977) did his own fair share of historical mish-mashing. But Wolper did not hesitate to celebrate Lincoln, or, for that matter, Richard Nixon (in a series of Republican party films in 1972), and celebration seems to be what Snee finds most reprehensible in the formulation of “public memory.”

Appreciating the outsize figure Lincoln has cut in American film-making has its virtues, and movie-goers who desire a good dose of Lincoln along with their popcorn are best advised to rely first on Reinhart for comprehensiveness, and then on Thompson for handling of themes and personalities (not to mention, in both cases, for the copious movie stills in both books, which Snee neglects completely). Snee, on the other hand, offers a pretentious and misleading direction, not only for understanding the ways we remember Lincoln, but for the nature of historical understanding itself.

Allen C. Guelzo, a three-time winner of the Lincoln Prize, is at work on a life of Robert E. Lee.