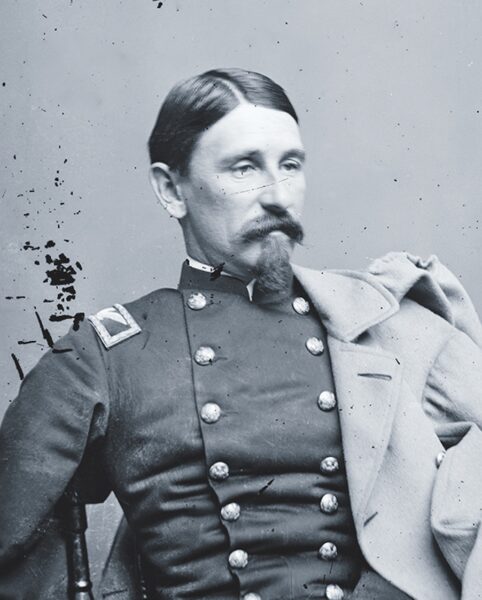

Library of Congress

Library of CongressColonel George Willard

Washington D.C., February 18th, 1863

This subject discussed in the following pages, is not attracting the attention which it appears to deserve. Late foreign publications have been examined, and many ideas on the subject have been introduced. If the attentions of the Officers on the American Army shall, by the arguments contained in this pamphlet, be directed to the consideration of the comparative value of rifled and smoothbore arms (particularly small arms), the attention of the undersigned, will be attained.

G.L. Willard,

Major U.S. Army, and Colonel 125th N.Y.V.

In 1862, Colonel George Willard of the 125th New York Volunteer Infantry was in winter camp when he wrote a pamphlet that he would have privately published. Titled “The Comparative Value of Rifled Musket and Smooth-bored Arms,” it advocated for the value of smoothbore weapons—in the face of the prevalent army ordnance culture that favored the use of the new rifle, or rifled musket, firing the French-designed “Minie” or Harpers Ferry Ball.1 Even today, Willard’s writings are worthy of consideration by students of the Civil War, its tactics and its arms.

Willard was a descendant of general officers who had served in both the American Revolution and the War of 1812. Born in New York in 1827, George did not seek an appointment to West Point but instead moved to Cincinnati as a teenager to pursue a career in business, a path his family considered less dangerous than soldiering. But with the outbreak of the Mexican War in 1846, Willard joined the 15th U.S. Infantry and was soon made first sergeant and cited for gallantry at Chapultepec. Then in 1848, Major General Winfield Scott recommended him for brevet promotion to second lieutenant in the 8th U.S. Infantry. By the start of the Civil War, Willard had risen to the rank of captain.

In 1861, Captain Willard raised the 2nd New York Infantry. However, regulations prohibited regular army officers from taking volunteer regiment positions while keeping their regular army rank. Willard was not willing to lose his regular army rank and so was unable to take command of the regiment. He would go on to serve with the Army of the Potomac’s Regular Army brigades during the Peninsula Campaign and was promoted to major in the 19th U.S. Infantry, a unit he at times commanded.2

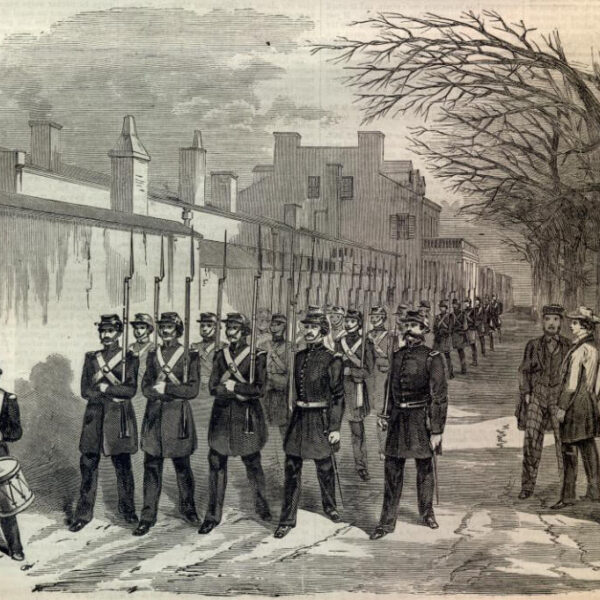

In 1862, the regulations governing regular army officers taking volunteer positions changed, and in August Major Willard was able to accept the appointment as colonel of the newly raised 125th New York Infantry.

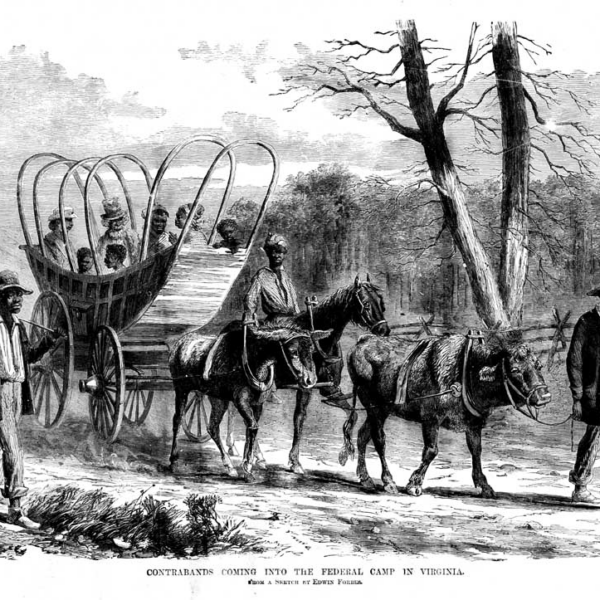

In September, Willard’s regiment of green troops was assigned to the garrison of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Soon finding themselves surrounded by Major General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Confederates (this during Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Maryland), the 125th, along with the other Federal forces of the garrison, surrendered without firing a shot.

The 125th, along with the other New York regiments of its brigade (39th, 111th, and 126th), would soon be paroled and sent to the Federal parole at Camp Douglas near Chicago. Exchanged in early November, Willard’s regiment (along with the rest of the brigade) traveled back to Washington, D.C., where, much to their embarrassment, the men learned they had earned the sobriquet “Harpers Ferry Cowards.” After spending the winter assigned to the outer defenses of Washington, the brigade was assigned to the command of Brigadier General Alexander Hayes, a fiery West Point combat officer who spent the ensuing months thoroughly drilling the soldiers.

By late June 1863 the brigade would join the Army of the Potomac on its march north to Gettysburg. On June 28, Hayes was promoted to command of the Third Division of the III Corps, with Willard taking command of the brigade.

Over the previous winter, Colonel Willard had had time to reflect on his experience as a combat soldier—and on the lack of training and combat experience of his regiment. This, along with conversations with other veteran officers, certainly informed his thinking in writing “The Comparative Value of Rifled Musket and Smooth-bored Arms,” which was published in 1863 and in full in several northern newspapers. There are parts of his argument about the value of smoothbore vs. rifled muskets that remain worthy of note.

One of Willard’s arguments pertained to the lack of marksmanship training volunteer soldiers received during the war. For the rifled musket to be used effectively at long ranges (500 yards), the soldier had to be trained to correctly estimate distance and then adjust the rifle’s rear sight accordingly. In the hands of a trained soldier—and under ideal conditions—this could be done. However, Willard made the point that the chaos of combat prevented both raw and veteran soldiers from making these sorts of calculations. Instead of arming all troops with rifled muskets, Willard advocated for arming one regiment in each brigade with that weapon and training the men in its use. This regiment would be trained for use as light infantry; the other regiments of the brigade would be armed with smoothbore muskets.3

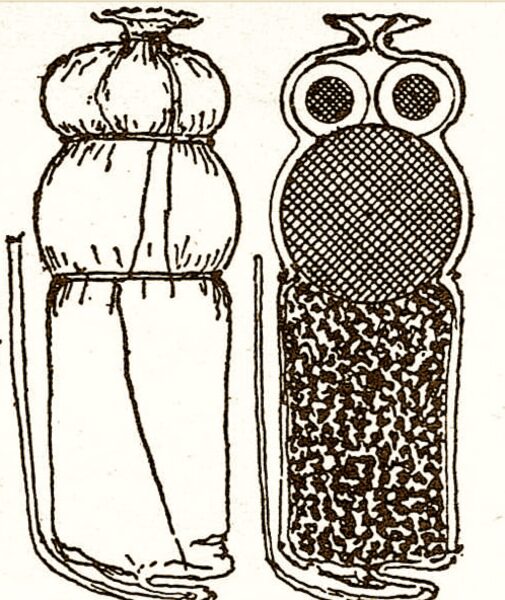

National Park Service

National Park ServiceBuck and ball ammunition (as shown in this illustration) consisted of one .64-caliber round ball and three .31-caliber buckshot.

The average range of distance separating combatants in the Civil War was approximately 100 yards—well within the effective range of the smoothbore muskets firing buck and ball ammunition, consisting of one .64-caliber round ball and three .31-caliber buckshot.4

Willard’s tactical philosophy reflected his combat experience. Under certain circumstances, he advocated a spirited advance, bayonets fixed, to within effective smoothbore range of the enemy. Then a volley, followed by a spirited bayonet charge.

While Willard’s arguments for the continued use of the smoothbore musket would not be adopted by military officials, they had validity. Some specific actions during the three-day Battle of Gettysburg can be cited in their favor:

July 1, 1863: In the late afternoon, elements of the Army of the Potomac’s I Corps found themselves making their “last and hopeless stand” at a barricade of rails on Seminary Ridge. A slight lull in the battle took place as William Dorsey Pender’s fresh Confederate division formed for its assault. Pender’s men advanced from McPherson’s Ridge, which was 500 yards from the Federal position. While the Federal artillery batteries opened fire at that range, the I Corps units, all armed with either Enfield, Springfield, or Austrian Lorenz rifle muskets, held their fire until the Confederate troops were “within easy range.” This was well within the 125-yard effective range of the smoothbore musket and shows that, while veteran infantrymen could have started firing at a longer range, these troops, even when armed with the “modern” rifle musket, held their fire until the enemy was within “easy” range.5

July 2, 1863: Also during the late-afternoon fighting, the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry, under the command of Major St. Clair Mulholland, moved through the Wheatfield to meet the advance of Joseph B. Kershaw’s Confederates toward Stony Hill. Mulholland would later write: “The Confederates were on a crest while the regimental line [of the 116th Pennsylvania] was below them, their feet about on a level with the heads of the men. When the [116th] Regiment charged and gained the ground on which the enemy stood, it was found covered with their dead, nearly every one of them being hit in the head or upper part of the body…. The large ball (calibre 69) and three buck shot with which the pieces were loaded, although a wretched ammunition for distant firing, was just right for close hand-to-hand work, and so, on this occasion the fire of the Regiment was terrible in its effect, while the small rifle balls of the South Carolina men went whistling over the heads of the men of the One Hundred and Sixteenth.”6

July 3, 1863: The men of the 12th New Jersey (Third Division, Second Brigade, II Corps) were in position just to the south of the Brian Farm barn when the Confederate advance known as Pickett’s Charge stepped off from Seminary Ridge. The 12th was armed with U.S Model 1842 smoothbore muskets and used buck and call ammunition. Before the charge began, the men of the regiment had modified their cartridges by removing the .69-caliber round ball and replacing it with up to two dozen .31-caliber buckshot. They also had gathered up as many discarded muskets as they could find and loaded them in the same way. Major General Alexander Hays, who commanded the 12th’s division, ordered the men to stay low and not to open fire until the advancing Confederates were within 50 yards. Riding down the line, Hays gave the command to fire, yelling, “Show them your colors and give them hell, boys!” The Confederates to their front were almost annihilated, with many of the survivors taken prisoner.

And what of Willard and his “Harpers Ferry” brigade? After several days of forced marches, the brigade arrived on the Gettysburg battlefield late on July 1, going into bivouac near the soon-to-be-famous Round Tops. Early the next morning, the brigade would be moved into position near the Brian Farm, where the men had a ringside view of the day’s actions, particularly on the Federal left, where James Longstreet launched his massive assault on the III Corps position near the Peach Orchard and along Emmitsburg Road.

In short order, Willard’s brigade would be ordered to the Federal left to try to halt the Confederate advance. Accompanied part of the way by Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, Willard would form the brigade along the lower reaches of Cemetery Ridge (near where the Pennsylvania monument is today). Having ordered his men to fix bayonets on their rifle muskets (a mix of Enfield P53s and Springfields), Willard advanced them toward the swampy brush swale that marked the course of the almost dry streambed of Plum Run. William Barksdale’s Confederates had just entered the area from the west. Willard’s brigade began shooting, but he immediately ordered them to cease fire as there was some uncertainty whether the troops in the swale were friend or foe. The question was answered when Barksdale’s men unleashed a strong volley into the ranks of the Harpers Ferry Brigade. Willard quickly realized his mistake and ordered the 125th and 126th New York regiments to charge.7

Yelling “Remember Harpers Ferry” and firing as they moved, Willard’s troops pushed Barksdale’s brigade out of the swale at the point of their bayonets, mortally wounding Barksdale. Continuing its advance 175 yards beyond the swale, the brigade (less the 39th New York) was stopped by Confederate artillery fire. Willard gave the order to retire, and just as the brigade reached the swale, he was struck by an artillery round shell that “tore the angle of his mouth and shattered his chin and shoulder.”

Willard died instantly. He was 35.

The fighting on July 2, 1863, was Willard’s first and last action as brigade commander. Given the opinions expressed in his pamphlet, might he have wished his untried volunteers had been armed with smoothbores loaded with buck and ball ammunition when they closed with Barksdale’s brigade?

As for Willard’s hard-luck “Harpers Ferry Brigade,” its charge into the swale not only stopped Barksdale’s advance, which threatened the left center of the Federal position, but erased the stigma assigned to the “Harpers Ferry Cowards.”

Phil Spaugy is a native Ohioan and lifelong Civil War enthusiast whose research focuses on the arms and accoutrements of the Federal infantry soldier. During his 46 years as a member of the North South Skirmish Association (N-SSA), he has live-fired almost every type of weapon issued to the soldiers on both sides

Notes

1. “Comparative Value of Rifled and Smooth-bored Arms” by Colonel George Willard. Cornell University Library.

2. Willard was on detached duty from the 19th U.S Infantry, which was serving in the western theater during the Peninsula Campaign.

3. A variant of this concept was used by many units during the war. For example, in a regiment of 10 companies, eight should be armed with smoothbore muskets firing the buck and ball ammunition. The remaining two companies should be armed and trained in the use of the rifle or rifled musket. These two companies would serve as the skirmish companies for the regiment. This concept was used by many of the early volunteer regiments until those regiments could be armed in their entirety with the rifle musket. In the case of many Federal regiments, mostly in the western theater, this was not done until mid-to-late 1863.

4. See Earl Hess, The Rifle Musket in Civil War Combat (Lawrence, KS, 2016), 107–109.

5. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series 1, Volume 27, Pages 245–281.

6. Brevet Major General St. Clair Mulholland, The Story of the 116th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (New York, 1996), 136–138.

7. The 39th New York was detached from the brigade and engaged in the fight to recover the guns of Watson’s Regular Battery. The 111th New York was on the brigade’s right flank and would join the center regiments’ charge in short order.