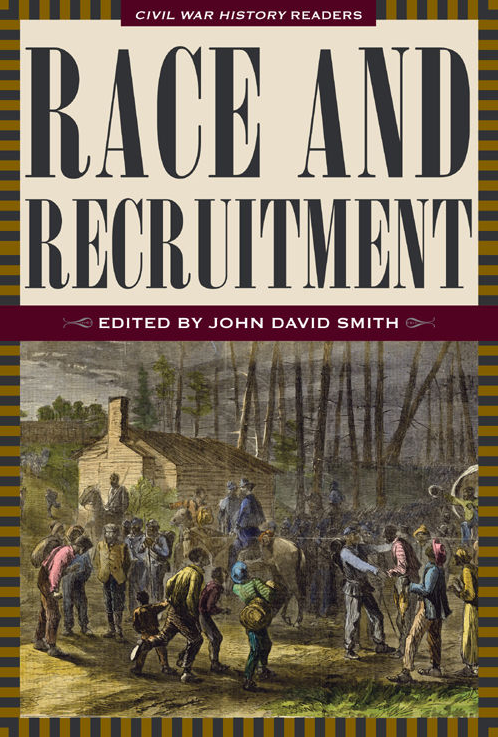

Race and Recruitment edited by John David Smith. Kent State University Press, 2013. Paper, ISBN: 9781606351802. $29.95.

In recognition of Civil War History‘s 60th anniversary, the editors at Kent State University Press are releasing a series of books that feature some of the journal’s most important publications. The essays in the present volume, edited by John David Smith, cover a broad swath of the recent historiography of slavery, abolitionism, emancipation and memory. While the book is ideal for a graduate level course on the historiography of the Civil War era, given the narrow focus of many of the essays, it is unlikely that it will appeal to the general reader.

In recognition of Civil War History‘s 60th anniversary, the editors at Kent State University Press are releasing a series of books that feature some of the journal’s most important publications. The essays in the present volume, edited by John David Smith, cover a broad swath of the recent historiography of slavery, abolitionism, emancipation and memory. While the book is ideal for a graduate level course on the historiography of the Civil War era, given the narrow focus of many of the essays, it is unlikely that it will appeal to the general reader.

The opening essay by Eugene Genovese takes readers back to 1959 and his critique of Stanley Elkins’s thesis, which posited that the repressive atmosphere of the plantation rendered slaves incapable of rebellion. Genovese’s critique helped to usher in a wave of scholarship that treated slaves as agents in the creation of a plantation culture. Unfortunately, Smith foregoes providing any examples of this new scholarship from the journal and moves on to two essays that explore abolitionist communities. The first, authored by Lawrence Friedman, explores the Gerrit Smith circle of abolitionists and distinguishes them from their Garrisonian and Tappanite allies based on such factors as age and belief in voluntarism. Reinhard Johnson’s essay on the Liberty Party in Massachusetts situates the organization within the broader abolitionist community and highlights its efforts to bring about moral and social change through political action.

The next grouping of essays challenges the rise of an interpretation popularized by Lerone Bennett in the pages of Ebony Magazine in 1968 that characterized Lincoln as a racist and white supremacist. Don E. Fehrenbacher situates Lincoln’s public statements denying racial equality within the context of his political campaigns, most notably during his 1858 run for an Illinois Senate seat. Michael Kurtz examines Lincoln’s support of the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, while Allen Guelzo offers a close reading of Lincoln’s August 1863 public letter to James C. Conkling. Guelzo identifies it as the strongest defense of Lincoln’s decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and recruit black soldiers into the United States army.

Closely related is Mark Neely’s analysis of Major General Benjamin Butler’s claim that in February 1865 Lincoln admitted the impossibility of sectional reunion as long as blacks remained in the country. It’s a claim that continues to resonate in certain circles, but Neely demonstrates that it is best understood as a self-serving, postwar fabrication.

For an edited collection of essays titled Race and Recruitment, the only disappointment is the lack of coverage of the black military experience. The closest the anthology comes in this regard is John Cimprich and Robert C. Minfort Jr.’s essay on the documentary evidence surrounding the massacre of United States Colored Troops at Fort Pillow in April 1864 and Donald Shaffer’s essay on the discrimination faced by black veterans in securing pensions from the federal government. Both subjects add immeasurably to our understanding of the war, but it leaves the black military experience on the battlefield largely unexplored. Without a closer look at Civil War History‘s index, it is unclear whether this gap reflects the editor’s choice or a broader scholarly emphasis over the years.

The radical shift from a war to preserve the Union to one that included emancipation and black recruitment is explored in two essays with a narrow focus on key individuals. David Blight deftly explores Frederick Douglass’s commitment to a memory of the war as an apocalyptic and millennial event that transformed a sinful nation and ultimately led to black freedom through the bloodletting of its citizens —as well as its president. Brooks D. Simpson traces Ulysses S. Grant’s evolving views on emancipation and recruitment of black soldiers by looking closely at the influx of refugees into Union camps and continued resistance on the Confederate home front which, according to Simpson, explains his acceptance of “hard” war by the summer of 1863.

The final two essays reflect recent scholarly interest in questions related to historical memory and the Civil War. No book has been more influential in the field than David Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2001), which argues that Americans (veterans included) largely brushed aside an emancipationist memory of the war in favor of sectional reunion by the beginning of the twentieth century. Andre Fleche directly challenges Blight’s thesis by demonstrating that a shared wartime experience between black and white soldiers carried into the postwar period. White Union soldiers did not abandon their black comrades in favor of a reconciliationist and segregationist interpretation of the war. M. Keith Harris also rejects the Blight thesis. According to Harris, Union veterans maintained a stubborn posture in their commitment to keep slavery and emancipation as central features in their postwar writings, resulting in a distinctly Northern memory of the war.

All in all, this is a valuable collection of essays. Despite some minor quibbles, these essays represent some of the best writing in the field from Civil War History. They provide the reader with a sense of how the field has evolved over the past few decades and where we might be headed in our understanding of the Civil War era.

Kevin M. Levin teaches history at Gann Academy in Massachusetts. He is the author of Remembering the Battle of the Crater: War as Murder (2012) and can be found online at Civil War Memory.