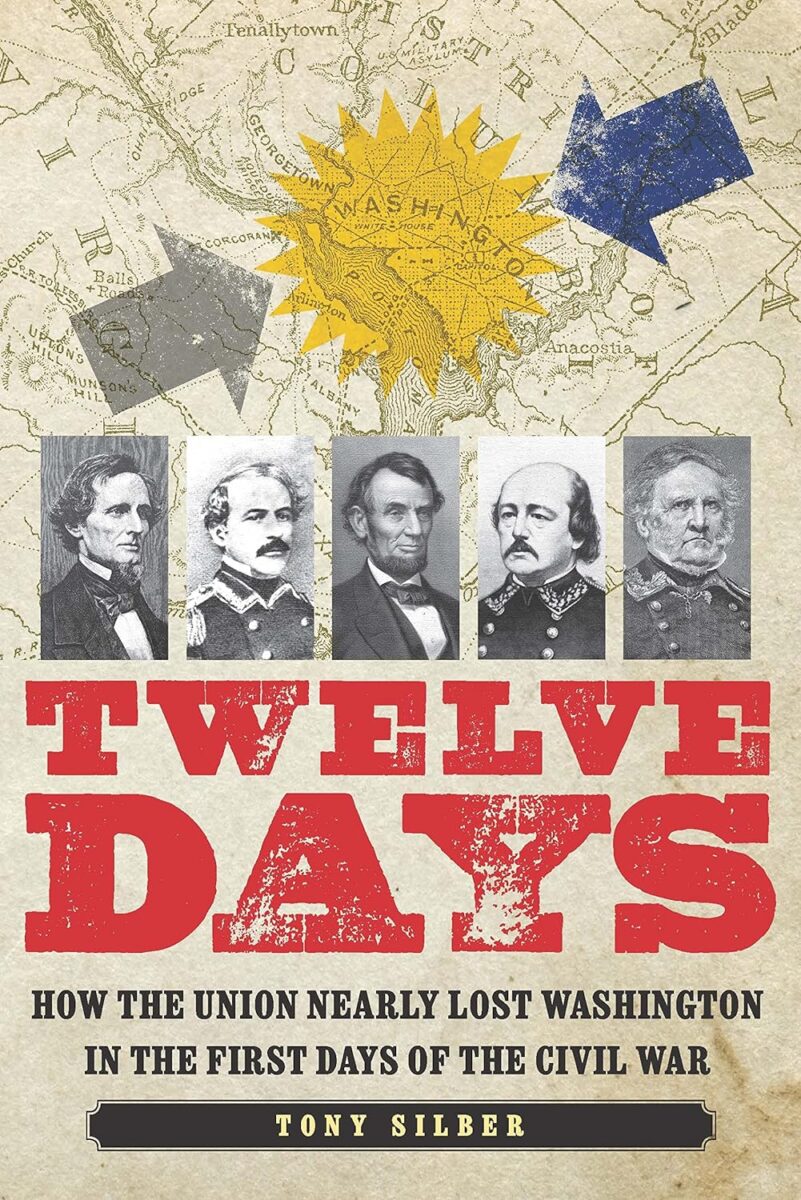

Historical consensus has long held that the greatest threat to Washington, D.C., during the Civil War came during Confederate General Jubal A. Early’s invasion culminating at the Battle of Fort Stevens on July 11-12, 1864. In Twelve Days, journalist and media mogul Tony Silber makes a compelling case for an alternative scenario: namely, April 14-25, 1861, the twelve days following the fall of Fort Sumter.

After the Confederate capture of the federal bastion in Charleston harbor on April 14—and before the arrival of the New York Seventh Militia Regiment on April 25—Washington City was surrounded by slaveholding states. Its local population was rife with seditious elements. There was only a ragtag collection of about 2,000 poorly trained militia available to defend it. The seat of government of the United States of America was ripe for the taking by an organized attack from a determined enemy.

That attack never come. “The nation’s capital,” writes Silber, “never came so close to being captured by the Confederates as it did in that short span.” Silber maintains that it was “only due to a series of specific acts by many participants on both sides that the worst didn’t happen that April.”

How the city survived this period of peril is told by Silber in a deeply researched, propulsive narrative that puts the reader in company with ordinary citizens on the streets of an unsettled city. The result is a page turning history of the highest order, peppered with insightful details that make clear these twelve April days were a period that could have profoundly altered the course of the war and the fate of the nations for years—if not decades—to come.

In the wake of the firing on Fort Sumter, President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to quell the rebellion. Previously moribund northern militias, particularly in Massachusetts and New York, now mobilized. Five companies of ragtag Pennsylvania militia made it through Baltimore on April 18. But the next day, the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment had to fight a riotous mob as it made its way across the city, leading to the Civil War’s first casualties. Southern sympathizers, with the tacit support of Maryland’s governor and Baltimore’s mayor, destroyed six bridges and cut two railroads north of the city. For seven days, Washington City was completely cut off—no trains, no telegraph, no newspapers, no information at all.

Silber makes two narrative decisions that enhances the immediacy of his story telling. First, he tells the story from the ground level, “from the perspective of the participants themselves.” Secondly, he has chosen to tell the story in real time, “chronologically, alternating among the three main scenes of action—Washington, the advance of the Northern troops, and the Southern planning and military movements.” This gives his narrative a ‘you are there’ immediacy; the reader knows what the participants knew and only when they knew it.”

With a keen eye for the telling anecdote, Silber also introduces the reader to numerous ancillary players who contributed to the events being played out during these dramatic days: Lucius Chittenden, the Treasury Department employee whose personal journal provides a man-in-the-street perspective of the Lincoln administration; Colonel Charles Pomeroy Stone, inspector general of the Washington militia, struggling to turn clerks and farmers into an effective defending force; Addison O. Whitney, twenty-one, of Lowell, Massachusetts, probably the first member of the Sixth Massachusetts Infantry to be killed on Pratt Street in Baltimore during his regiment’s bloody march between railroad stations; William Stoddard, Lincoln’s less famous third secretary, who wrote extensively about activities in the White House; and Samuel Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, Baltimore Railroad, who played an unacknowledged role in getting Northern troops to Washington via Annapolis Junction, thus avoiding bloody Baltimore.

Silber gives President Lincoln, just seven weeks on the job, high marks for decisions large and small during the twelve-day crisis. He suspended habeas corpus in Maryland and delayed calling Congress into session, trusting it would later sanction some of his extraconstitutional actions; he likewise refused to accede to Southern emissaries urging him to recognize the Confederacy and send the Northern troops home. “President Lincoln,” opines Silber, “with his sharp intellect, his gift for strategy, his media say, and his basic humanity, held the country together in these first weeks of the war—just as he would for the next four years.”

Gordon Berg is an independent scholar who writes from Gaithersburg, Maryland.