Library of Congress

Library of CongressRégis de Trobriand

Perhaps no battle resonates as deeply in America’s collective memory as Gettysburg. Its tale is timeless: For three days in the hot Pennsylvania summer of 1863, thousands of soldiers in blue and gray clashed over the fate of America. Immortalized in countless books and movies, reenactments and monuments, the famous battle is carved into world history.

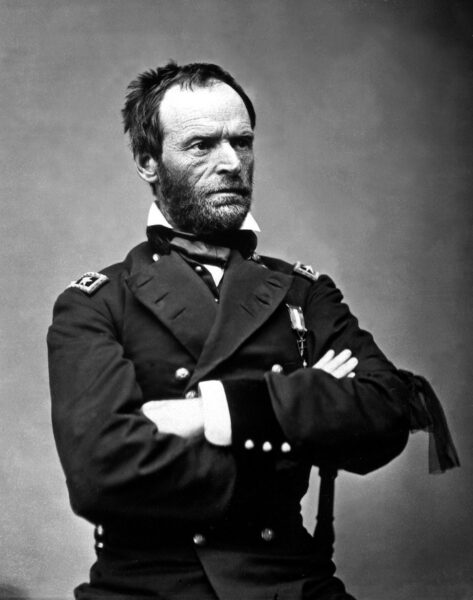

Yet the story of Gettysburg remains far from complete. Attempting to craft minute-by-minute, unit-by-unit accounts of the engagement, various historians have only intensified longstanding disputes over what actually happened there. In doing so, however, students of the battle have largely overlooked a controversy surrounding one of the battle’s most fascinating figures: Régis de Trobriand, French immigrant and Federal brigade commander.

While not as popular as Robert E. Lee or Joshua Chamberlain, Trobriand is familiar to Civil War historians. Commanding a brigade in Daniel Sickles’ III Corps, his resolute defense and heroic countercharge on July 2, 1863, saved the Union position on the infamous bloody Wheatfield.1 Gettysburg’s chroniclers have remembered him well. While Edwin Coddington’s seminal battle study highlights Trobriand’s performance, more recent authors—notably Stephen Sears and Allen Guelzo—have praised him for “clinging stubbornly” and holding on “with the bayonet.”2 Harry Pfanz, widely regarded as the expert on the Battle of Gettysburg’s Second Day, was even more direct, extolling Trobriand’s countercharge as a “gallant holding of his position.”3

My reevaluation of Trobriand rebuts this established record. Claims of his courageous stand and fearless counterattack rely more on his own postwar mythmaking than verifiable fact. I contend that Trobriand was not the Wheatfield’s hero, but an opportunist who retroactively claimed credit for contributions that were not his. Bolstered by original, recently uncovered archival evidence and innovative technological analysis, my study promises to alter the Frenchman’s historical reputation and correct enduring flaws in the memory of Gettysburg’s famous Wheatfield.

Latter-Day Lafayette

Like thousands of other immigrants who pledged to defend the Union, Régis de Trobriand cut a colorful swath in the Army of the Potomac. Heir to ancient Breton nobility, he was 25 when he immigrated to the United States in 1841 and settled comfortably into the haute société of New York City. As the antebellum period progressed, Trobriand established himself as the lead editor of the Courrier des États-Unis, the premier French-language newspaper of the Western Hemisphere.4

That genteel lifestyle ended abruptly when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter. As Lincoln issued a call for volunteers, Trobriand saw the war as a chance to reclaim “the destiny which had [been] deprived [him] in France.”5 Fashioning himself as heir to an earlier French immigrant who had famously fought alongside George Washington—the Marquis de Lafayette—Trobriand raised a regiment from the city’s Franco-American community. His 55th New York Infantry, the “Guardes de Lafayette,” mustered in August 1861; they would form the only ethnically French regiment to see combat during the war.6

The Guardes de Lafayette were given their baptism of fire in May 1862 at the Battle of Williamsburg, during the Peninsula Campaign. Casualties whittled the regiment’s strength and as 1863 dawned, the 55th merged with another regiment, the 38th New York. In the aftermath of the Union defeat at Chancellorsville in May, Trobriand received a promotion. Now leading the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, III Corps, Trobriand—untested and inexperienced as a brigadier—found himself at the center of one of the most consequential military campaigns in American history.

The Bloody Wheatfield

In early June 1863, Trobriand and his brigade began to react to the larger events taking place in the war’s eastern theater. Rebel general Robert E. Lee eyed an offensive that would strike into the Federal heartland, bringing the Army of the Potomac into hot pursuit. By the end of June, Trobriand’s brigade had reached the Mason-Dixon Line, campaigning as far north as Emmitsburg, Maryland.

Meanwhile, in southern Pennsylvania a chance encounter between Union cavalry and Confederate infantry on July 1 was unfolding into monumental battle. Only miles away, Trobriand’s brigade was among the first reinforcements to reach Gettysburg the following day; filling out the Union left, Trobriand’s men had to adapt to Sickles’ infamous decision to overextend his III Corps’ line. Soon, the brigade became responsible for covering the apex of a massive salient near the Rose farm.7 Confederate general James Longstreet eyed this tempting target, and it soon became clear that Trobriand’s thinned line was in trouble.

According to the traditional narrative, this was the Frenchman’s finest moment. For over two hours, his men weathered the storm and fended off multiple Confederate onslaughts. Occupying positions in and around the bloody Wheatfield, Trobriand first provided reinforcements to repel a Rebel assault on Devil’s Den.8 His men then struggled in a brutal hand-to-hand contest where, as one Union veteran later recalled, “hundreds were killed.”9 Though taking high casualties, Trobriand’s men repelled waves of Confederates. But renewed Rebel offensives injected a fresh surge of violence. Attacked on three sides from elements of two Confederate divisions, the line began to buckle; Trobriand had no choice but to withdraw.10

But all was not yet lost. Spotting reinforcements from Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps, Trobriand decided to conduct a delaying action to buy time and hold the line until it was reinforced. Gathering the tattered remnants of three regiments—the 110th Pennsylvania, the 5th Michigan, and the 17th Maine—his “retour offensif” singlehandedly succeeded in “keeping the enemy at bay.”11

It was this “aggressive return” that enshrined Trobriand’s name in Gettysburg history. Plugging a gap in the Federal line, his charge prevented a breakthrough and subsequent Confederate rout. Saving his adopted nation in its darkest hour, it seemed as if the immigrant brigadier had lived up to his role as Lafayette’s heir.

National Park Service

National Park ServiceA modern-day view of the Wheatfield at Gettysburg

Reevaluating the Record

Trobriand served out the remainder of the war with the Army of the Potomac, and his supposed heroics at Gettysburg grew to mythic proportions in the following decades—inflated, in large part, by Trobriand himself.

When the war ended, the Frenchman sat down to compose a memoir of his service titled Four Years with the Army of the Potomac. Originally published in French, Trobriand sought to correct what he viewed as “errors industriously disseminated” in his home country about the American war.12

However, correspondence between Trobriand and Ulysses S. Grant also casts the work as a tool of postwar American foreign policy. In France, Emperor Napoleon III had long expressed sympathy for the Confederate cause. The narrative of a French national who had dutifully defended the Union, Four Years was intended to combat this pro-southern view and repair American relations with France.13 Crafting himself into a Franco-American savior, Trobriand presented Gettysburg as the pinnacle of his service. In essence, he became a hero because he claimed to be one—and generations of historians, from Coddington to Guelzo, have accepted this narrative.

Amid this postwar mythmaking, the most important and authentic account of Trobriand’s wartime service—his campaign journals—got forgotten. Throughout the war, he had maintained a diary as a daily record of events; his writings would eventually span nine volumes, which he sealed and mailed home from the front to his daughter.14 Scrawled in near-illegible French shorthand, the journals never received the publicity of Four Years. Trobriand’s grandson later donated them to West Point’s Archives and Special Collections, where they languished in obscurity.15

The indecipherable nature of Trobriand’s journals and a lack of awareness regarding their existence have precluded their use in Civil War historiography. But their unvarnished account of his wartime service—absent the politicking of Four Years—proves crucial to understanding the man. By rediscovering these journals, translating them into English, and pairing them with other contemporary primary sources, I have gained a never-before-seen look into Trobriand’s performance at Gettysburg.

An Innovative Investigation

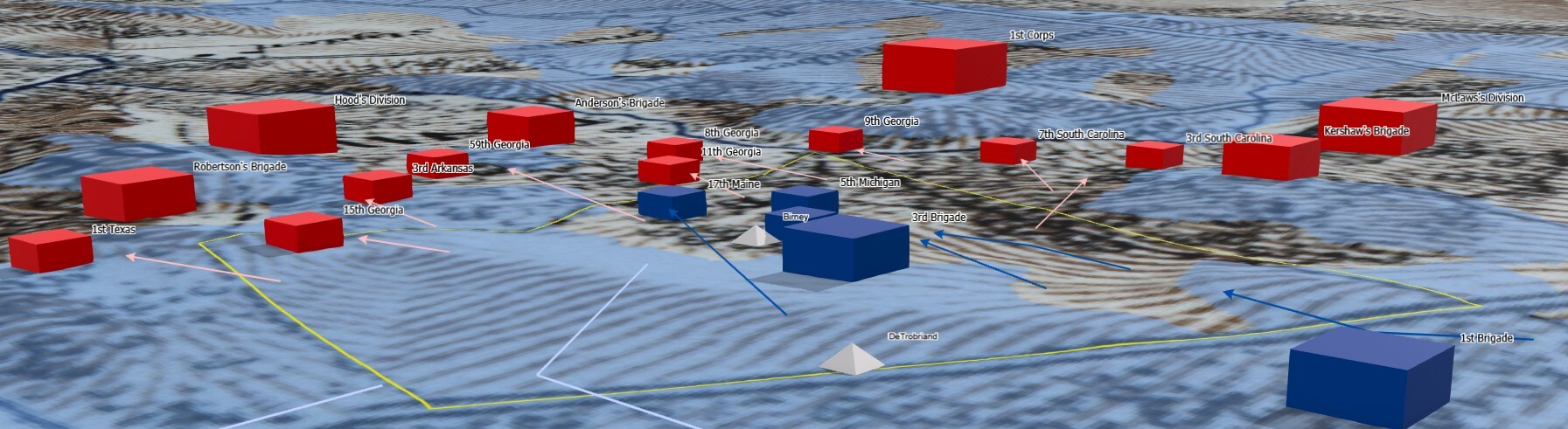

In reevaluating Trobriand, however, I have considered more than just his century-old diaries; applying digital software to the battle, my study also offers a unique, technology-driven intervention in the historiography. Using a modern application known as ArcGIS Pro, I have developed new digital maps informed by primary source accounts to provide a novel, three-dimensional assessment of the Wheatfield fight.

I first leveraged ArcGIS Pro’s georeferencing capability to reconstruct Trobriand’s campaign route to Gettysburg. This tool overlays historical maps on modern, satellite-based imagery to display period-specific locations and settlements that may no longer exist. Cross-referencing Trobriand’s journals with the surviving accounts of individual soldiers from his brigade—Captain Edwin Houghton, Captain Charles Mattocks, and Private John Haley—allowed me to create the first known map of Trobriand’s operational maneuvers.

The centerpiece, however, remained his performance at Gettysburg. As with the campaign, ArcGIS Pro offered an innovative link between past sources and present technology. In particular, the program’s viewshed analysis tool provided a unique, never-before-seen view of the Wheatfield fight. This capability took mathematical inputs related to perspective—such as Trobriand’s height, the stature of the horse on which he was mounted, and the level of smoke and vegetative obscuration—to craft a digital overlay of what the Frenchman could and could not see from his location at particular points during the battle.

To effectively leverage the viewshed analysis tool, I first created a series of three-dimensionally rendered battle maps depicting each phase of the Wheatfield fight. A painstaking web of primary sources, including Trobriand’s newfound journals, the aforementioned accounts of his soldiers, regimental histories, and extracts from the Official Records yielded the location and movements of the units and Trobriand. Applying multiple viewshed analyses to these maps and comparing them helped determine whether Trobriand was the true hero of the Wheatfield.

Matthew Clifford

Matthew CliffordViewshed analysis (in blue) reveals Trobriand’s perspective at the moment of his charge at the Wheatfield.

Righting Trobriand’s Wrongs

What did the archival and technological breakthroughs reveal about Trobriand at Gettysburg?

Combining primary sources with georeferenced maps to reconstruct Trobriand’s route illustrated that he chronically mismanaged the campaign to Gettysburg. The trouble began early on. Unlike the patriotic hero he later claimed to be, Trobriand’s journals reveal that he wished to muster out of the army after Chancellorsville; he only continued for opportunistic reasons, “in [his] interest or that of [his] career.”16 Upon heading north, he cited “terrible” weather, as “marching under a torrid sun and amidst a suffering dust” left the brigade in a weakened state.17 Yet he also expressed disdain for the men under his authority, deriding his sergeants as “decidedly ignorant.”18

Alternate sources corroborate Trobriand’s poor campaign leadership, causing subordinates to chafe under his domineering command. As the march to Gettysburg wore on, Captain Edwin Houghton lamented that the “commanding general” had created an “inhuman wager” to race his unit against another brigadier’s; Trobriand thus made the march unnecessarily grueling.19 He also forced his brigade to drill incessantly, while many soldiers complained of insufficient rations.20 The most dramatic expression of the unit’s resistance to Trobriand came at Gum Spring, Virginia. Colonel Thomas Egan, a regimental commander who felt slighted by the brigadier, confronted him there; in a mutinous “passage of arms,” he “actually attempted to take the reins” of the brigade “into his own hands.”21 Clearly, Trobriand’s men did not view him as a gallant, heroic leader; left out of Trobriand’s memoirs, these tensions never made it into the historical record.

By the time Trobriand’s men reached Gettysburg, they were exhausted, degraded, and ill-prepared to fight. Charting their approach on ArcGIS Pro truly demonstrated Trobriand’s problematic campaign leadership. Georeferencing the brigade’s route revealed the duration of their hardship for the first time; almost day-by-day, the map highlighted how the brigadier’s authority over his men withered. Constructing the campaign on ArcGIS Pro, therefore, supplemented the archival evidence to illuminate Trobriand’s conduct. Indeed, he was not the brigade’s valiant leader—but an inexperienced, opportunistic commander whose poor decision-making angered his soldiers.

Pairing contemporary accounts of the Wheatfield fight with viewshed analysis undercut the centerpiece of Trobriand’s heroic legacy: his famed countercharge to hold the Union line. While he claimed that he “drove a charge across the valley, stopping the enemy’s developments for some time,” eyewitnesses recalled a decidedly different performance.22 Private John Haley of the 17th Maine, for example, instead remembered his panic-stricken brigadier frantically issuing an order to “fall back, right away!”—a directive that Haley’s entire regiment ignored.23 A similar report remarked on Trobriand’s alarm; in thickly accented French, he allegedly wailed to his men that “ze whole rebel army is in your rear!” It appears Trobriand did not organize his famous counterattack, but rather called for the opposite—a premature withdrawal.

Library of Congress

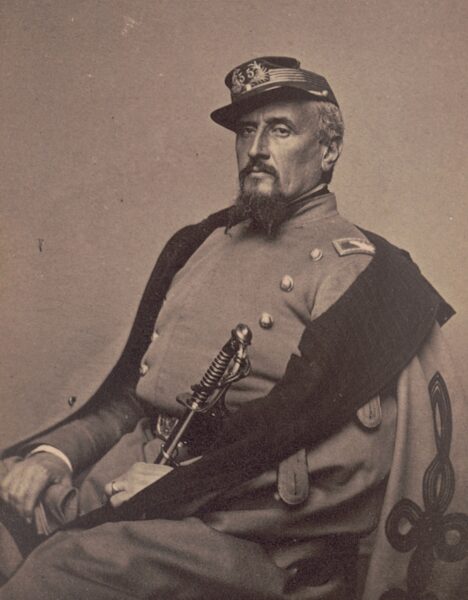

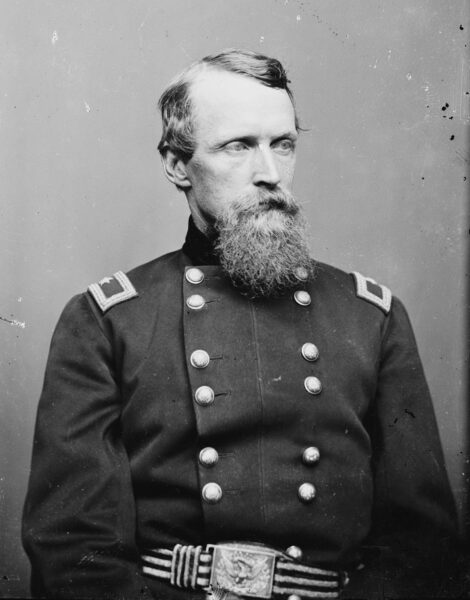

Library of CongressDavid B. Birney

Who, then, was responsible for holding the III Corps line at the Wheatfield until reinforcements arrived? My investigation points instead to Trobriand’s division commander, Major General David B. Birney. The soldiers of Trobriand’s brigade consistently reported Birney’s presence at the crucial moment of the charge, with Captain Charles Merrill remembering him “rid[ing] on the field and directing our line to advance.” Birney himself corroborated the claim in his after-action report, noting that men of the brigade responded to his “personal appeal” to charge—not Trobriand’s. In short, archival evidence suggests that Trobriand took credit for the heroism of David Birney.

Comparing the viewshed analyses of Trobriand and Birney at the moment of the counterattack supplements the argument against the Frenchman. Whereas Trobriand likely could not see the entire Wheatfield, Birney’s position gave him an excellent view of the coming Rebel onslaught prior to the counterattack. Evidence also suggests that the division commander reached the site of the counterattack before Trobriand. Coincidentally, Birney became ill during the Siege of Petersburg and died in 1864, having never cast himself as the hero of the Wheatfield and allowing Trobriand to claim responsibility.

Of course, the technological renderings of ArcGIS Pro alone were insufficient to discredit Trobriand. Used in conjunction with contemporary accounts, however, the viewshed analysis offers an important data-driven addition to my reassessment of the Wheatfield. Considering both damning eyewitness reports and digital mapping technology, the truth becomes clearer: the French brigadier does not seem to have led the critical charge in the Wheatfield. Instead, he took credit for Birney’s gallantry.

***

Trobriand’s service encapsulates many important themes that characterize the American Civil War. An immigrant who risked his life for the United States, he clearly sought acceptance, honor, and glory on the battlefield. Closer inspection reveals motivations that were also opportunistic in nature, as was the case for many Civil War officers. Attempting to live up to the legacy of the Marquis de Lafayette, he portrayed himself as a hero in his memoirs. That self-crafted reputation has solidified in Gettysburg’s historiography, cultivating an erroneous interpretation of events in the Wheatfield and undercutting the genuine heroism of figures like David Birney.

Amid this distortion of reality, Trobriand’s story reveals an essential truth that stands at the core of the Gettysburg saga: forever after, memory of the battle loomed large among Union and Confederate veterans. That fascination has survived through generations, but it remains the work of the historian to separate fact from fiction for an accurate portrayal of Gettysburg. As the story of Régis de Trobriand shows, those three fateful days of July 1863 still offer much to learn.

Cadet Matthew Clifford is a senior at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Combining his major in American History with a minor in French, his research leverages digital techniques to explore the issues of identity and memory among immigrant populations during the American Civil War. He intends to continue his research on immigrants in the Civil War before applying the analytical and digital mapping skills he has developed to a career in the Military Intelligence branch of the United States Army. For more on his research on De Trobriand at Gettysburg, click here.

Notes

1. Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day (Chapel Hill, NC, 1987), 266.

2. Stephen W. Sears, Gettysburg (Boston, 2003), 286.; Allen C. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (New York, 2013), 285.

3. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day, 266.

4. Marie Caroline Post, The Life and Memoirs of Comte Régis de Trobriand: Major-General in the Army of the United States (New York, 1910), 189.

5. Régis de Trobriand, Four Years with the Army of the Potomac (Boston, 1889), 57.

6. Ibid., 72.

7. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day, 130.

8. De Trobriand, Four Years with the Army of the Potomac, 496.

9. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day, 247-250.; Edwin B. Houghton, The Campaigns of the Seventeenth Maine (Portland, ME, 1866), 92.

10. Régis de Trobriand to Fitzhugh Birney, July —, 1863, War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols (Washington, D.C., 1880-1901), Ser. 1, Vol. 27, pt. 1, 520 (hereafter referred to as OR).

11. Régis de Trobriand to Fitzhugh Birney, July —, 1863, OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 27, pt. 1, 520.

12. De Trobriand, Four Years with the Army of the Potomac, v.

13. Post, The Life and Memoirs of Comte Régis de Trobriand, 344-345.

14. Régis de Trobriand, Papers, Box no. 1, USMA Library Archives & Special Collections, United States Military Academy, West Point, NY.

15. Ibid.

16. Régis de Trobriand, Journal no. 4, May 31, 1863, Régis de Trobriand, Papers, Box no. 1, USMA Library Archives & Special Collections, United States Military Academy. Translated from French to English by Matthew Clifford. Hereafter referred to as Trobriand Journal, USMA Archives.

17. Trobriand Journal, USMA Archives, no. 4, June 15, 1863.

18. Ibid., June 6, 1863.

19. Houghton, The Campaigns of the Seventeenth Maine, 73.

20. Charles Mattocks, “Unspoiled Heart”: The Journal of Charles Mattocks of the 17th Maine, ed. Philip N. Racine (Knoxville, 1994), 41.

21. John W. Haley, The Rebel Yell & the Yankee Hurrah: The Civil War Journal of a Maine Volunteer, ed. Ruth L. Silliker (Camden, ME, 1985), 94.

22. Trobriand Journal, USMA Archives, no. 4, July 2, 1863.

23. Haley, The Rebel Yell & the Yankee Hurrah, 101.

24. Allen S. Shattuck, “Third Infantry: Address of A.S. Shattuck,” in L.S. Trowbridge and Fred E. Farnsworth, eds., Michigan at Gettysburg: Proceedings Incident to the Dedication of the Michigan Monuments upon the Battlefield of Gettysburg, June 12th, 1889 (Detroit, 1889), 76.

25. Charles B. Merrill to Benjamin M. Piatt, July 5, 1863, OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 27, pt. 1, 522.

26. David B. Birney to Orson H. Hart, August 7, 1863, OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 27, pt. 1, 485.