David Hochfelder discusses the vital and often unseen role of the telegraph during the Civil War.

Transcript

John Heckman: David, thank you for coming on to talk about something that we haven’t really thought about in a long time as far as in my little circle of peers in American Civil War studies, and that is the telegraph and media history.

David Hochfelder: My pleasure. Thanks for having me on, John.

John Heckman: You’ve written a number of things about media and electricity and technology, and as I said, I wanted to introduce this kind of thing to a new audience. And some people have heard about the telegraph, but maybe they don’t know exactly how it works or maybe even what it is, they’ve just read about it on a line of a book. What is the telegraph and how does it operate?

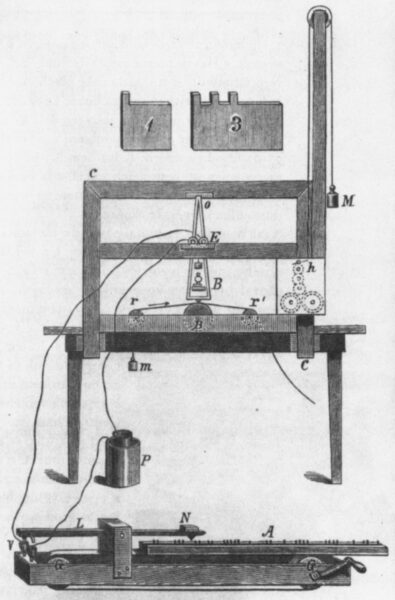

Wikimedia

WikimediaSamuel Morse’s original telegraph design

David Hochfelder: That’s a great question. One of the ways I got into my research when I was in graduate school was confronting this very simple question. This is going to be a roundabout answer, but I will answer directly after kind of a windup. One of the puzzles that I found in this history was how Samuel Morse, who was an artist, he was a painter, how he wound up inventing a communications revolution. And one of the conclusions I came to is that the telegraph is a fairly straightforward technology. It requires some knowledge of electricity. And I’m not going to belabor your audience with how Samuel Morse acquired the knowledge. He made strategic partnerships, is the short answer.

But it’s a fairly simple technology. It’s a battery, it’s a length of wire, it’s an on-off switch, and it’s an electromagnet that creates a sound, a click, or records marks onto a moving strip of paper. So it’s not a steam engine level of complicated. It’s a fairly straightforward technology. And once Joseph Henry discovered some of the principles of electromagnetism and built magnets that could be worked or actuated at great distances from the battery, very sensitive, small magnets, once Henry did those things, the telegraph was inevitable and was probably going to be invented by someone. And there were around 60 competing designs. Morse’s design turned out to be the most straightforward and that’s why Morse’s design had greatest commercial success, at least in the United States. So it’s a fairly simple technology. Morse’s great innovation—again there are 60 other competing telegraph designs using electricity, not to mention optical or semaphore telegraphs that were used in harbors or the French government had set up during the Napoleonic Wars—Morse’s great innovation was the relay. His insight was, Oh, if you could actuate a magnet, say at a distance of 10 miles, why couldn’t you simply kick in a fresh battery like a relay of horses? That I think was his pivotal invention.

So, again, to answer your question directly, the telegraph is a fairly straightforward piece of technology, doesn’t require a lot of skill to build. Some skill, obviously, but it doesn’t require a lot of scientific knowledge or engineering or technical skill.

John Heckman: How do those who operate this actually learn how to operate it? Is it just like going into a shop and you’re basically what we would call in the modern day interning with someone to learn how to do this and to understand telegraphy?

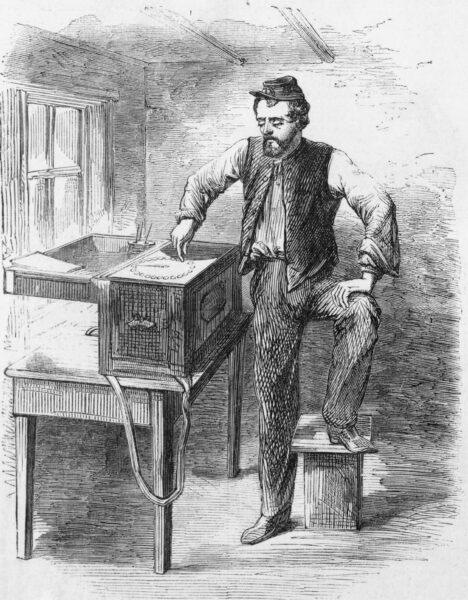

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyAn army telegraph operator at work

David Hochfelder: Early in the industry, there really wasn’t any kind of formal training. Toward the end of the 19th century, you get telegraph schools similar to business colleges that taught typing and shorthand and that sort of thing. But early in the industry, you didn’t have any kind of formal training. And, for purposes of the Civil War, I looked at the experiences of several operators, including an Illinois resident named William Gross. And Gross, basically like most telegraph operators, learned by hanging around the telegraph office. And the apprenticeship model, as you suggested a minute ago, is a pretty apt description. Andrew Carnegie, same way. He was a messenger boy in a telegraph office and he learned how to operate just by hanging around telegraph operators. So it was really an informal training system.

One of the interesting things about the training is Morse’s original design marked dots and dashes on a moving strip of paper. And you would have to have an operator who would read out visually the dots and dashes to make the letters. Sometime in the early 1850s, several operators realized they could copy by ear. And telegraph companies really discouraged this practice. But operators were like, you know, look, we can copy faster by listening to the clicks and the magnet. So, that was kind of an innovation in training, in training themselves really, but an innovation in training how to become a telegraph operator. One of the things was learning how to copy by ear.

John Heckman: How were those skills developed when we’re talking about things like conflict, about the need to use this technology perhaps in a new way? How was that evolution occurring in the middle 19th century?

David Hochfelder: The U.S. Military Telegraph Corps, just like the U.S. Military Railroads, was set up basically as one of the logistics wings of the U.S. Army. And they hired experienced operators. They didn’t do on-the-job training. And there was a lot of demand for telegraph operators in the U.S. Military Telegraph Corps. They weren’t paid great. There was at least one example of a strike in William Gross’ area of operations. And commercial operators were generally paid better if they stayed at their commercial telegraph companies. So there really wasn’t a lot of innovation in operations or training during the war. The emphasis was on building the lines, getting messages through, etc. Even during the war, the U.S. Army had the military telegraph system, but even with the presence of the U.S. Military Telegraph, the military still relied on commercial lines for a lot of non-urgent military traffic. So, battlefield logistics and operations, U.S. Military Telegraph network was primarily used. For more routine communications that were not as time sensitive, the commercial lines handled that traffic. And operators would often work for both operations, the commercial company and the U.S. Military Telegraph. Again, the example of William Gross when he was at the Cairo, Illinois, office, he worked for the Southwestern Telegraph Company and the U.S. Military Telegraph.

John Heckman: So was there a kind of marriage or collaboration between the telegraph and the railroad stations and such? Is that where this begins or does it come about in a different way?

David Hochfelder: During the war, the relationship between the telegraph and the railroad is not, in my judgment, terribly significant. The U.S. Military Telegraph built lines along railroads when they could. But the railroad network in the South was not that well developed. The relationship between the telegraph and the railroad industries really arises because Western Union after the Civil War realizes that it’s a lot cheaper to build lines along railroad lines, telegraph lines along railroad lines. And they work out exclusive rights of way contracts with railroads that prohibit any other telegraph company from accessing a railroad line. So the railroads would get free telegraph service from Western Union, and in exchange, Western Union would be able to maintain and refurbish their lines much more cheaply than, say, if the lines were on a public highway.

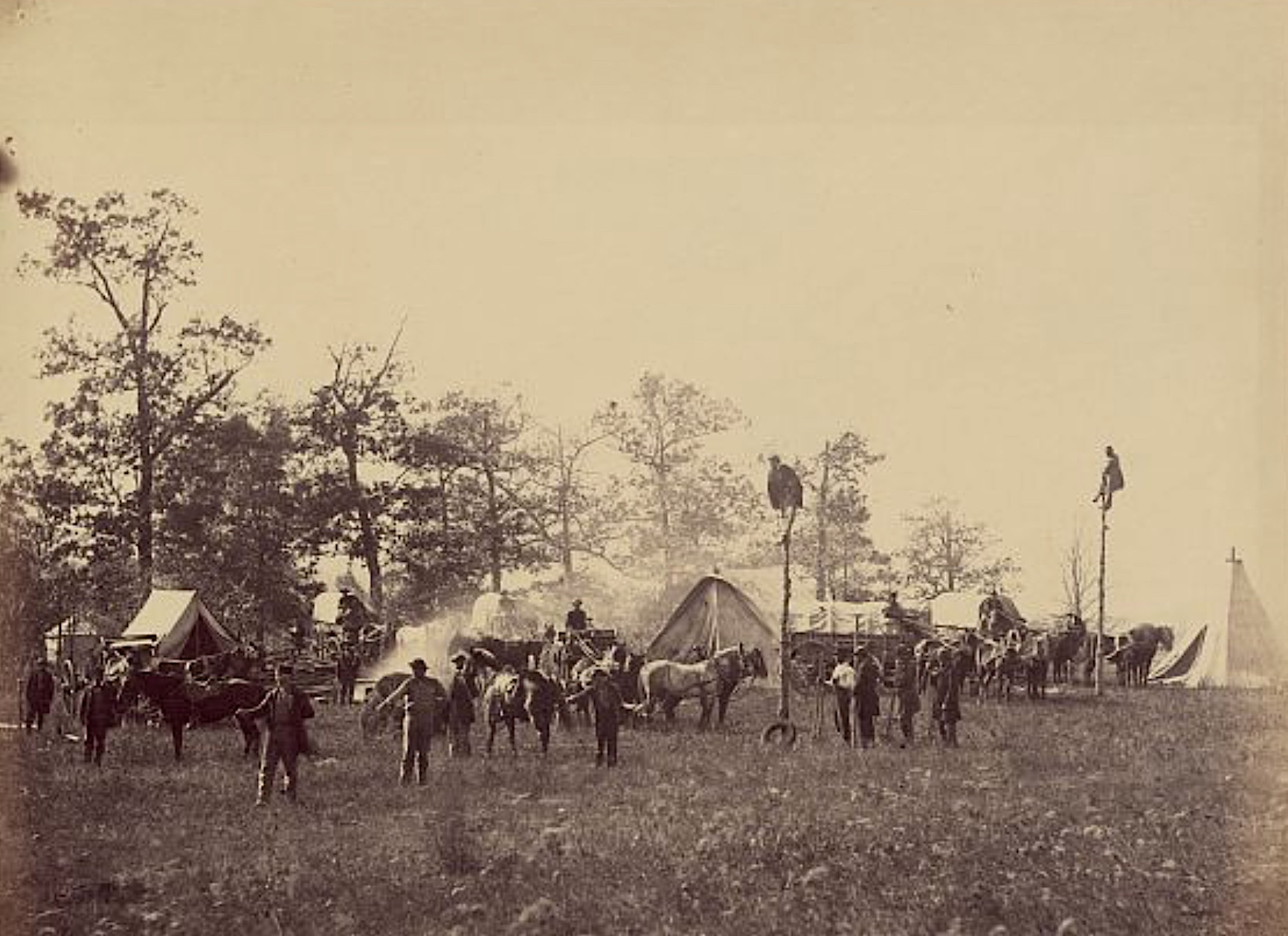

Library of Congress

Library of CongressU.S. Military Telegraph construction corps

John Heckman: How does this new information superhighway, if you will, of the mid-19th century influence news for people who are trying to get the latest information from the front back at home? How does this influence journalism if it does it all?

David Hochfelder: Yeah, it has a great influence on journalism. The New York Associated Press was set up in the late 1850s by a consortium of six or seven New York daily newspapers. And the idea behind the Associated Press was that overseas news—we didn’t have an Atlantic cable yet, that’s 1866—would come by steamship to New York Harbor or Boston Harbor. And the New York newspapers would control the flow of international news and then send out digests to newspapers around the country that subscribe to the associated press’ wire service. And that model is still kind of present today with the Associated Press and Reuters and Axios. So, the Associated Press was already set up to handle national and international news.

What I discovered in the course of my research is that a lot of historians of technology and communications say, Oh, the telegraph was this revolutionary innovation in communications. And that’s true. But just because you have a telegraph network doesn’t mean that everyone is using it. The president of a telegraph company testified to Congress in the 1870s that only one out of 200 residents of Pittsburgh had occasion to use the telegraph in any given year. So if a half percent of the population is actually using the telegraph, how did it transform something like journalism or finance?

And you have to keep in mind that the telegraph is a fairly expensive medium. A 10-word message could cost 25 cents, 50 cents, and a letter cost 3 cents. So for ordinary communication purposes, the vast majority of Americans were just fine with a 3-cent letter. So the telegraph was an expensive medium. It was mainly used by businessmen, financiers, and newspapers to handle time-sensitive information where someone would gladly pay a premium because the information being transmitted was more valuable than the high cost of sending it.

That said, what I concluded is that most Americans encountered the telegraph not through sending their own messages, but through the pages of their newspapers. And especially during the Civil War, you see this as a real pivotal moment in creating what we would now call the news cycle. During the First Battle of Bull Run, for example, people would flock to the telegraph office in a hotel in Washington, D.C., for example, and every 15 minutes or so there would be updates from the battlefield. So people would stand outside a hotel or a telegraph office waiting for the latest dispatches from the battlefield to be posted onto a public bulletin board essentially. The same thing happened when President Garfield was shot. People would stand outside the hotel or telegraph office waiting for updates about his health condition. Oliver Wendell Holmes famously remarked that a friend of his thought he was turning into an idiot because he would read the same dispatches in different newspapers as if they were fresh news. So people really developed a hunger for timeliness in news during the Civil War, waiting for news of battles and so forth.

John Heckman: So would you say that we need to tread lightly when we’re saying things like the telegraph revolutionized the mid-19th century? We really have to not make that kind of a generalization? We have to say, well, what did it revolutionize? Or how did it revolutionize this for these people in particular or the military?

David Hochfelder: Yeah. That’s exactly well put. In the field of the history of technology there’s been a decades-long debate that probably will never get settled and I think gives a lot of vitality to the field: Does technology drive history or does society shape technology? And the answer is yes. It’s a little bit of both. So if you’re going to claim that a technology was revolutionary in its social effects, I don’t have a problem with that. But then your job is exactly what you say: How exactly did something like the telegraph change society or change individual psychology? So making a sweeping claim is fine as long as you can support that claim. And that’s one of the things I tried to do in my book is say, Okay, how did the telegraph change particular aspects of society and individual psychology? And the development of the news cycle is a great example of how the technology influenced how people thought about the news, that it changed expectations and behaviors around the news.

John Heckman: If these armies want to get information back for the news or just to be able to communicate with Washington, D.C., for example, what kinds of issues could they face with deploying these systems? What could make it more difficult or more strenuous or take more time than maybe a lot of people would consider when they’re talking about the telegraph being used by Civil War armies?

David Hochfelder: That’s a great question. There’s obvious issues with building and repairing lines in hostile territory. There’s a lot of incidents where in occupied Tennessee or Arkansas, for example, linemen for the U.S. Military Telegraph would get sent out to repair lines that guerrillas had destroyed or cut and they would be attacked. So it’s not unlike the more recent examples of Iraq and Afghanistan, where insurgents would lay in wait for American troops. It’s the same kind of guerrilla warfare. So linemen especially could be subject to those hazards. Operators could also be caught in the thick of battle. There are about a thousand, I want to say, 1,200 operators in the U.S. Military Telegraph and the casualty rate for them was comparable to the casualty rate for soldiers generally. Obviously, they were not frontline infantry, but neither were the vast majority of U.S. Army personnel. So, they were exposed to the same sort of personal dangers that regular military troops were subject to.

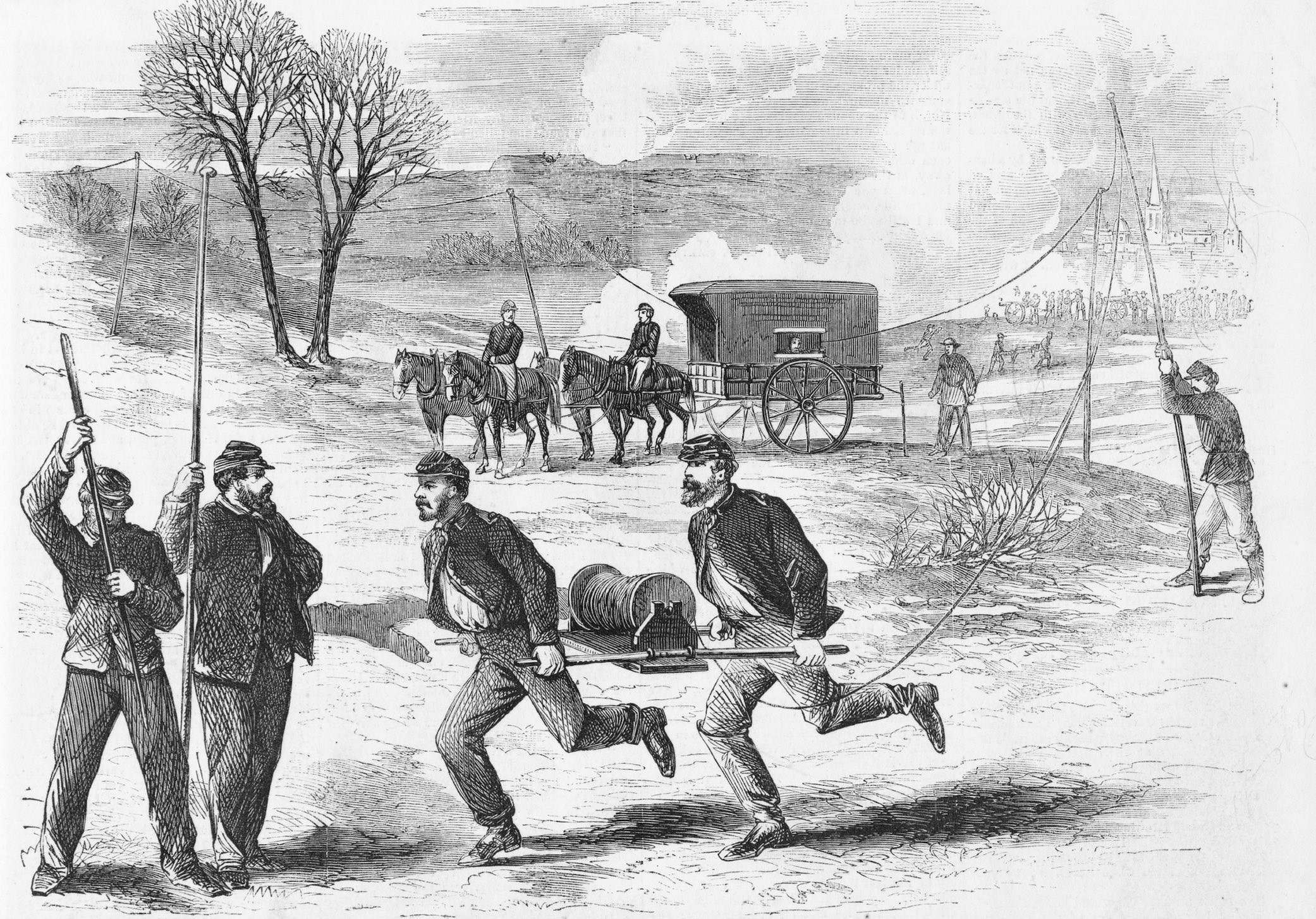

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyArmy telegraph workers setting up lines under fire.

John Heckman: When you’re discussing logistics and you’re talking about just the massive amount of things that need to be transported, communicated across various lines, how does this also impact what you think of when you think of intelligence gathering or getting this information to the proper person? We know that, for instance, President Lincoln loved to be in the telegraph office getting information from the front. Other people who are involved in intelligence gathering have to be involved in one way or another with the telegraph. How do you think this impacts that idea of gaining intelligence about movements and direction and what is needed by the army in the field?

David Hochfelder: Yeah, that’s a great question. The U.S. Army set up a rival system to the U.S. Military Telegraph, a field telegraph system that evolves into the signal service and then the Signal Corps after the war. And that was intended to be used for purposes like what you suggest, intelligence gathering, operations on the battlefield in real time. The U.S. Military Telegraph network was really used for—you mentioned Lincoln being in the telegraph office—was really used for coordinating strategy and large-scale operations from the War Department to the various commands.

So the U.S. Military Telegraph network was less involved in intelligence gathering. The field telegraph system was more involved with operations in the field, as the name suggests, including intelligence gathering. I want to also stress for your listeners, a great book is David Homer Bates’ Lincoln in the Telegraph Office. And the scenes in the movie Lincoln with Daniel Day Lewis about Lincoln being in the War Department telegraph office, a lot of that is based on Bates’ memoir. So it’s a great book. If your listeners are not familiar with it, I would strongly suggest that for a good firsthand view of what the War Department telegraph office was like and how Lincoln spent a lot of time there.

John Heckman: If you could go back and see the telegraph office in action, what do you think that would mean to you as far as the impact it would have on you as a researcher? As a person who looks back in the history of this type of media form?

David Hochfelder: In accounts the telegraph operators left after the war, there was a group, sort of like the Grand Army of the Republic but for telegraph operators, who would have annual reunions. And the proceedings of their annual reunions are at the New York Public Library. And I drew upon them to get a sense of operator culture. There are a lot of stories about hard drinking, for example, among telegraph operators. And that’s born out also by some of the archival research. William Gross, when he ran a division in southern Illinois and Missouri, instructed his staff to allow drinking on the job, but only in moderate quantities. And there’s an account from one of these U.S. Military Telegraph reunions that the operators at a particular corps headquarters convinced the commanding general that if battery acid was unobtainable that whiskey could substitute for battery acid, but only if it was of the highest quality. So, I would like to go back and observe, if that were possible, to go back and observe actual living and working conditions that operators experienced.

John Heckman: What was that veterans’ organization like? Because I don’t think a lot of people have ever heard of it. I know I’ve never heard of it. What was that like and what are some of the other stories about their wartime experience that you uncovered?

Library of Congress

Library of CongressU.S. Military Telegraph Corps operators at Bealeton, Virginia, in 1863

David Hochfelder: There’s a process of nostalgia that follows every war and kind of in a similar way, including, say, World War II. The way that it operated is, after the war, veterans didn’t really want to talk about their experiences. When they hit middle age, around 35 or 40, enough time has elapsed where the trauma has maybe eased and they’re willing to reminisce more. So, like the Grand Army of the Republic struggles for membership until sometime in the 1870s, same thing with the telegraph operators. Reunions are sparsely attended for the first few years, and then as these men hit middle age, they become more and more active. And a lot of it is reminiscences about, again, camp life, drinking, pranks they played on each other. Telegraph operators really enjoyed pranking each other. So a lot of it is really rose-colored nostalgia. And that was something I wanted to understand, is this process of not wanting to deal with the war for the first few years after returning home and then becoming nostalgic for it as these men age. And again, I think it’s a similar phenomenon with World War II, with the VFW or the American Legion, where in 1946, 1947, the men just want to get on with their lives, get married, return to their jobs, start families. And then maybe around age 40, they’ll gravitate toward the local VFW post. So I think it’s a similar process of nostalgia.

I also want to emphasize that the reason for this veterans’ organization of telegraphers, the main purpose of its existence was to lobby the federal government to declare them eligible for military pensions. They were not eligible for military pensions. Only people who held army ranks were eligible. U.S. Military Telegraph operators and linemen typically did not hold military ranks except at the upper echelons, because this was technically part of the Quartermaster Corps. So, to get supplies you needed an officer—lieutenant colonel, colonel, captain—who could requisition supplies for the telegraph lines. But by and large, the rank and file of the USMT were not members of the U.S. Army. So they were not eligible for pensions and in fact never received military pensions despite, again, enduring the same privations that U.S. Army troops endured and suffering a similar casualty rate.

They wound up getting pensions around the turn of the century from Andrew Carnegie as a personal donation. But I just want to stress that the main reason for this veterans’ telegraph organization was to lobby to be treated on the same level as military personnel.

John Heckman: How do you think that wartime experience of the men who are part of this telegraphy movement contributed to the expansion of telecommunications in the U.S. afterward?

David Hochfelder: As far as how it influenced the industry, one of the reasons why the operators, especially those who remained in the telegraph industry, were nostalgic for their Civil War experiences was that in the last third of the 19th century, telegraphy goes from being a skilled occupation—it’s almost like being a translator, translating a foreign language. You know, copying a telegraph signal is similar to speaking a different language, learning a different language. But by and large, thanks to Western Union being a monopoly, the work is less well paid and is more onerous in the 1870s, 1880s, 1890s. And it’s become akin to secretarial work. And I think a lot of the reason for this nostalgia is the Civil War was this one moment where operators were in high demand and they were respected for their skills and they had a lot of on-the-job independence. So I think one reason for this nostalgia, outside of the normal nostalgia that happens when veterans return home, is that this was the one moment in their careers when they felt valued for their skills. Whereas they were being de-skilled and paid less and less well as time went on because Western Union was a monopoly.

John Heckman: When you speak to audiences or students about this subject matter, what’s one thing that you try to stress the most, or something that we get wrong a lot, or maybe we have a mythological look at it instead of looking at it for what it really was?

David Hochfelder: The main thing I would emphasize is that, again, going back to the revolutionary nature of a technology like telegraphy, you know how it changed society and individual psychology, it doesn’t do this all at once. And it doesn’t do this at the same pace for different social effects. So just because you have a technology or a network doesn’t mean that its impacts are immediate or obvious. So a great example of that would be the Atlantic cable. That’s an interesting history in and of itself. Suffice it to say that there were four or five attempts to lay a working Atlantic cable in the 1850s and 1860s. And finally, in 1866, there are two cables that work and the continents are placed in permanent electrical communication. So you’d think, Oh, okay, well great, now we can send telegrams from the United States to Europe. Great. This is a network accessible to everyone. It turns out that the Atlantic cable is extremely expensive. It was something like $10 a word when it first opened for business with a 20-word minimum. This is in 1866 dollars, gold dollars, not paper folding currency.

So, how valuable would the information have to be for you to spend $200, the equivalent of several thousand dollars today? How valuable would the information need to be for you to bear that expense? Now over time, the price drops to about 25 cents a word thanks to competition and more Atlantic cables being laid. And 25 cents a word is still an expensive proposition. So just because you have the technological capability doesn’t mean that it’s universally accessible or that its social and economic changes are instantaneous. That there’s a process of diffusion or dispersion, if you will, market adoption maybe is a better way to put it. And paying attention to that process is much more important than just saying, okay, so we have a telegraph network, and boom, we’re done.

John Heckman: I’m struck by the fact that now that I’m thinking about telegraphy during the Civil War, I’m seeing it as more of a small component of a much larger messaging operation. Because I’m also thinking about how many archival boxes I’ve gone through and I never saw some kind of written-down piece of information directly from the telegraph office, or I saw very few of those. So it’s almost like I’m seeing it through what you’re saying as this newer technology. It’s been around for about 20 years or so, but it’s still this kind of minor aspect of a larger messaging apparatus.

David Hochfelder: That’s an important point. And one reason why you may not be seeing many telegrams in archival collections is people tended to regard them as ephemeral. You get a 10-, 15-word message, you read it, you understand the message, and you dispose of it. There’s no need to keep it. Or less need to keep it than say a letter. So that’s one reason why you may not be seeing a lot of telegrams in archival collections. You do see a lot in the War Department records and—I’m sure your listeners are familiar with the multi-volume Official Records that the War Department put together in the 1890s—those will contain telegrams that survived. And you’ll see the original copies in entries in the War Department record group at the National Archives. But say the records of a business, you’re probably not going to see a lot of telegrams that survived because the information, again, it’s an expensive medium, so the information has to be time-sensitive and somewhat valuable. And because it’s time sensitive, once you do whatever the information is encouraging you to do, you don’t need to keep that record.

John Heckman: It’s also almost seeming to me like the early days of the internet. It was a military thing first, and it was expensive to have it. We had to pay by the minute or by the hour sometimes back when AOL was doing things. And then it became more accessible. It’s almost like that media was similar in that way, where the military’s using it more and the information is coming back for journalists, but your next-door neighbor isn’t going to the telegraph office to send information. But they may be going to the hotel to get access to the media.

David Hochfelder: Or reading the newspaper, looking at the Associated Press telegraphic dispatches. The other thing, in a more general way, you mentioned the internet being a military network first. There are very few innovations in American technology that arose strictly out of the private sector. Virtually every important technology in the past 200 years has had government support in one form or another. The telegraph did. Morse obtained a subsidy from Congress to build his first line. The railroads had enormous, massive federal subsidies in the form of land grants. The steamboat industry was subject to disasters, boiler explosions periodically. And the federal government set up the first consumer safety regulations in adopting a steamboat boiler code.

So there were very few technologies that had zero public support. This is maybe a useful historical perspective to have when federal support for research is at risk right now. I can’t think of a single technology that did not benefit from some form of public support.

About the Guest

David Hochfelder is an associate professor of history at the University at Albany and author of The Telegraph in America: 1832-1920.

Additional Resources

-

- U.S. Military Telegraph Corps

- David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office (1909)