Historian Megan L. Bever discusses the prevalence of alcohol in Civil War armies and the many issues that resulted from its presence.

Historian Megan L. Bever discusses the prevalence of alcohol in Civil War armies and the many issues that resulted from its presence.

Terry Johnston: Megan, thanks very much for joining me today.

Megan Bever: Absolutely.

Terry Johnston: Today’s question is from an anonymous reader who asks, “How prevalent was alcohol use among Civil War soldiers? Was it considered a problem? And if so, how was it dealt with?” Why don’t we start with the first part of that. How common was alcohol use in Civil war armies?

Megan Bever: That’s a great question and it doesn’t have a straightforward answer. The answer is that it was incredibly common, but also there were shortages. So it depends on where soldiers were. Federal soldiers had more access to liquor than their Confederate counterparts. That being said, Confederate soldiers found plenty of opportunities to scrounge up liquor—whiskeys or brandies for purchase, generally from civilians. Federal soldiers, it really depends on where they’re at. If they are in the eastern theater closer to Washington, D.C., or in Virginia, they probably have a steadier supply than they do, say, if they’re in the western theater or even further out in the trans-Mississippi, where you’ve got guerrillas disrupting supply lines.

So it’s not easy to get at, but the supplies varies. I would say Union soldiers, much more than their Confederate counterparts, have access to rations that are coming from a military source.

Terry Johnston: Let’s talk about that. People might not know this, and you write about this in your book, but during the Civil War there was something called a spirit ration in the armies. What exactly was that?

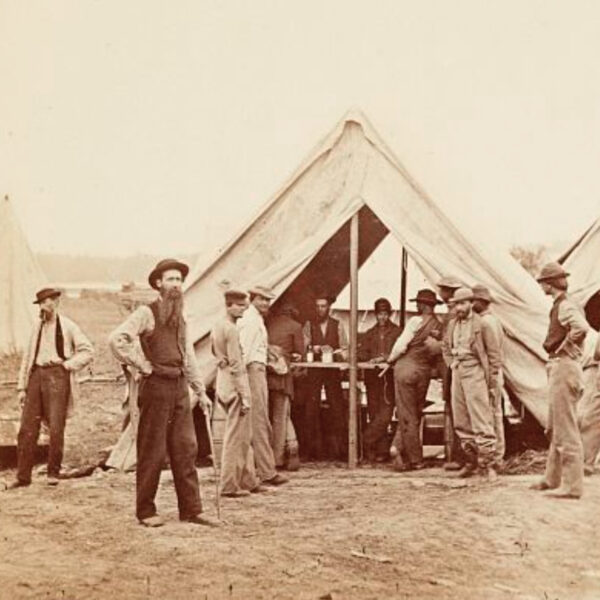

Library of Congress

Library of CongressA Union sergeant feigns drunkenness in a photo made during the Civil War.

Megan Bever: So, both the Union and the Confederate militaries, they use spirit rations, or a liquor ration, to promote health of soldiers. And this can be everything from using it to cut quinine to help guard against malaria, to treat wounds or illnesses, or something more nebulous, like using it to stave off exposure or to help soldiers be less fatigued if they’re doing something like digging trenches or building bridges or something like that. So, again, both Federal and Confederate forces use rations that way. Federal forces have a steadier access to the liquor they need, generally whiskey, to hand out those rations.

Terry Johnston: Another thing from your book that I found interesting is that even though these spirit rations were sanctioned by the military, whether troops received them could be dependent on who their officers were. So, if your officer was, say, a temperance man, he might not distribute the rations to his troops, right?

Megan Bever: Right. The military leaves it to the discretion of the commanding officer when troops should get liquor. So in some cases, you have commanding officers who are super pragmatic. You might even have somebody at the rank of general or colonels that are going to hand out rations to their troops when they think they need them, typically for health reasons or maybe to raise morale. But then you also have these other guys— Oliver Otis Howard is one of them. They don’t like liquor. They’re temperance proponents themselves. They abstain from drinking. And so they won’t give it to their soldiers. And it creates a haphazard access to liquor and some jealousy and some resentment among some of the soldiers.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. And another thing you wrote about is how there was a different standard when it came to alcohol use between officers and enlisted men. Officers were actually allowed to drink, right?

Megan Bever: Officers are allowed to keep liquor in their private stores. And that understanding, that permission had predated the war. It’s a perk of rank. Enlisted men are not allowed to keep liquor in their private stores. That doesn’t mean they never have it, but it’s contraband. So enlisted men have to wait. They either have to wait for an officer to decide he’s doling out rations, or they have to get it illegally. They have to find a civilian who’s selling it. They have to sneak in care packages from their family. But yeah, different ranks come with different privileges and it leads to different drinking patterns.

Terry Johnston: You mentioned packages from home as a source of alcohol. I think anyone who’s read a fair number of Civil War soldiers’ letters will recall seeing the pretty frequent request for people back home to include some kind of bottle of something in their next care package. I’m guessing doing so though was not officially approved. Did military officials search packages from home?

Megan Bever: Plenty of searches. And I think soldiers will grumble anytime there’s searches of care packages or mail. I think soldiers are assuming with some evidence that the men who are searching their packages are confiscating their liquor and then they’re drinking it. That’s the perk of the job. I think that Confederate soldiers maybe have an advantage here because they tend to get more visits from family members directly just because they’re stationed closer to their families and their homes. I saw more cases of Confederate soldiers managing to get a bottle or two of something from like a dad or an uncle when he came to visit.

There are also at least a few instances where Confederate soldiers are actually sending, or their families request them to send, the liquor or beer that they can access in the ranks, to send it home because there are shortages in the Deep South. So, there are actually some care packages going back and forth, or at least in the requests there.

But yeah, it’s not allowed in an official sense for people to send care packages with liquor in them.

Terry Johnston: Another source of liquor that was technically not allowed were the sutlers who followed the armies and frequently set up shop and camp, right? Were sutlers, by and large, the easiest source?

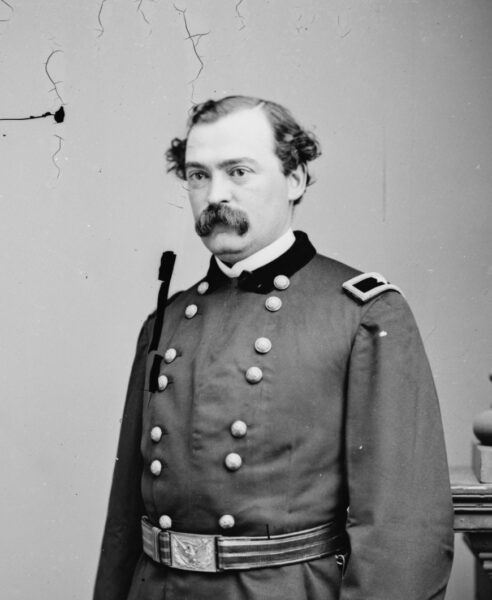

Library of Congress

Library of CongressA sutler’s tent in a Union army camp

Megan Bever: Again, I think it depends. I would probably say, this is so hard to enumerate, but I would say that it’s just civilians in general. Soldiers have more luck with farmers who are distilling whiskey or brandy on their farms. They can get liquor that way. Any time soldiers are in town, obviously that opens up a whole world of liquor and a whole world of problems because you have civilians selling in all different places.

Sutlers tend to be more common in Federal lines. And the sutlers, they’re merchants and they’re civilians but they’ve got licenses to sell. So they’ve got a contract basically to supply troops with luxury goods. So, extra clothes, snacks, candies, pies, liquor. Usually their contracts stipulate that they’re not allowed to sell liquor either at all or to enlisted men. But that doesn’t keep sutlers from doing it. You have a huge population of mostly young adult men. Sutlers find ways to sell on the sly. They will sneak liquors in and find funny ways, like they’ll bury it in the ground, but they have like a hose or a pipe that soldiers can get it out of. So some of the stories are funny. But you also have enlisted men that get violent if sutlers maybe are selling to officers but not to them.

Terry Johnston: This might be a question with an obvious answer, but what did you find about these soldiers who were really motivated to obtain alcohol? What were the most common reasons they were turning to it?

Megan Bever: Yeah, when soldiers think and write about their own drinking, they don’t describe it like the medical department, like soldiers are not really writing, oh, I’ve got to drink this whiskey from the sutler, I’m really worried about my malaria. Soldiers don’t write that. They’re much more likely to talk about homesickness, missing their families and drinking. They will talk about a fear of death. Some of them are really straightforward of just talking about their fear. But most of them talk about recreation.

There are some funny stories of guys just getting drunk, having parties, falling in the bushes. Telling other soldiers that they love them. Just the typical stories of young adults, teenagers drinking. If the medical department is describing the clinical reasons for needing to drink, soldiers very much are looking at the emotional reasons.

Terry Johnston: I know the holidays too were a great reason. I was reading recently about, I believe it was in 1863, when the Irish Brigade hosted St. Patrick’s Day, and the stories that these soldiers were telling about the strength of the liquor that was available to them, I mean, talk about funny stories.

Megan Bever: Right.

Terry Johnston: But that would’ve been something that was probably more, if not sanctioned, acceptable, right? Where it seemed like everyone was in on it, for this one day.

Megan Bever: Right. And I think, again, it kind of depends where you’re at and who your commanding officer is. Like these things might be officially against the rules, but if your commanding officer doesn’t care, no one else does either. Or maybe the one guy who wants to sleep cares, but no one else does. And I think when you have Irish-American or German-American regiments, there’s going to be a higher prevalence of drinking, even just like common, everyday drinking, not necessarily drunken revelry. There’s more tolerance because of the ethnic heritage and the cultural heritage those soldiers bring with them.

Terry Johnston: What about drinking as a way to cope with the fears associated with combat? On the one hand that was, I’m guessing, a rather acceptable reason to drink so far as your comrades were concerned. But then you had the many stories of leaders—officers—who were drunk in battle, and obviously that’s not good. Everyone who’s read Civil War history knows about certain charges against certain generals for being drunk, but was that really a big issue?

Library of Congress

Library of CongressBrigadier General James H. Ledlie

Megan Bever: I think so, and I think it depends on how you’re looking at it. Like in a macro sense, with a couple exceptions—maybe [Brigadier General James H.] Ledlie at Petersburg—you can’t really look and say, oh man, this guy’s drunkenness changed the course of the war, or something like that.

But soldiers draw a line, and it’s a different line than civilians draw, typically. Soldiers will make room for men who need to drink for their emotional or physical health. That’s understandable to them. Where soldiers get angry is when someone becomes abusive or violent. So if an enlisted man becomes ridiculously violent—guys who are prone to fighting, things like that—that’s seen as destructive and needless in a war that’s already bloody. But enlisted men really unleash on officers of all ranks that they think are mistreating them and misusing them because they’re drinking too much. So if officers are doing stupid drills or if they’re wasting supply—anything they could be doing that would deplete the energy that men have, which is limited, or put men in danger—there’s not really any tolerance for that, at least among the rank and file.

And so that’s where I see it. These little micro incidents just corrode morale and make men really, really frustrated. I can think of one instance of a Confederate soldier who writes that he’s going to desert. His commanding officer is so drunk that he’s like, “I’m going to desert and go join another regiment because I want to be of use to the Confederacy and I’m not being used properly here.” So, it’s an interesting way of thinking about military service.

Terry Johnston: Well, now that we’ve established that alcohol was indeed a common presence in Civil War armies, what—beyond the examples you’ve just talked about—were the other general issues that arose from this widespread presence of liquor?

Megan Bever: Yeah, I think it is that potential for violence and disorder. So, again, you’ve got a war that’s incredibly bloody and incredibly violent and troops that are not that disciplined because most of them are volunteers anyway. So if you have liquor running through the ranks, that complicates any kind of practice of discipline that you’re trying to institute. But what I found was that the biggest problems tended to pop up whenever soldiers are interacting with civilians. So it’s one thing if men are disorderly in camp, but they’re in camp amongst themselves, that’s a problem but it’s sort of contained.

But if soldiers are in towns, whether they’re passing through or they’re occupying different cities, it causes a bigger problem. If you’re Confederate soldiers, you get drunken soldiers in town and they harass civilians and it undercuts morale on your home front. And there are plenty of conversations in the Official Records about Confederate soldiers in rural Virginia, in the Shenandoah Valley, in Arkansas, where the soldiers are drunk and disorderly, like bordering on partisan activities. And it’s just corrosive for the Confederate war effort.

And if you look at Federal forces, if they’re in a town, it’s most likely Confederate or disputed. And if you’re trying to subdue and occupy a rebel population, you really don’t need soldiers running around drunk, right? That’s going to be antithetical to everything you’re trying to do.

I’m actually at the moment looking at how this plays out in Missouri, where I work. And it’s really interesting how drunken soldiers can exacerbate violence, that guerrillas really hurt the Federal effort to keep Missouri somewhat peaceful—at least not just have absolute chaos.

Terry Johnston: Right. And that’s interesting. I never really thought about it like that. Where, as an occupying force, you want to cause the least amount of disruption, especially with the folks you’re occupying, and drunkenness doesn’t help. So how did military authorities deal with instances like this? I’m sure there were a variety of punishments, but what did these look like?

Megan Bever: It depends. They have these really ineffective attempts to punish soldiers after the fact for getting drunk, sort of public humiliation. Some men have more serious offenses where they do actually get confinement or something like that.

In a more widespread attempt to control, you see both Union and Confederate governments curtail civilian abilities to sell to soldiers. So, in Washington, D.C., and Missouri, which I’m studying right now, and other occupied parts of the Confederacy, Union forces will let sellers continue with their liquor licenses and continue to sell, but it’s contingent on them not selling to soldiers. And if they sell to soldiers, they lose their license. So you’re actually putting the onus on civilians not to sell to soldiers because the military just doesn’t seem to have an effective way of keeping soldiers themselves out of establishments. It’s a multi-pronged approach.

Confederates are more likely to implement martial law that includes a prohibition on sales. There are seven Confederate states that actually pass prohibition on distilling, and that’s for more complicated reasons than soldiers drinking. But, basically you see civilians being brought in and having their rights to do business really curtailed in order to control the behavior of troops.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. And I’m guessing that this was a constant issue where, I mean, it’s just never-ending, right?

Megan Bever: Right.

Terry Johnston: It’s like Civil War whack-a-mole, it just keeps going on and on.

Megan Bever: Yes.

Terry Johnston: Well, because liquor was such a big presence, it’s probably not going to surprise any of our listeners that temperance reformers focused their efforts on saving soldiers from what they believed were the evils of alcohol. How did temperance folks go about doing this? What was their message to the troops?

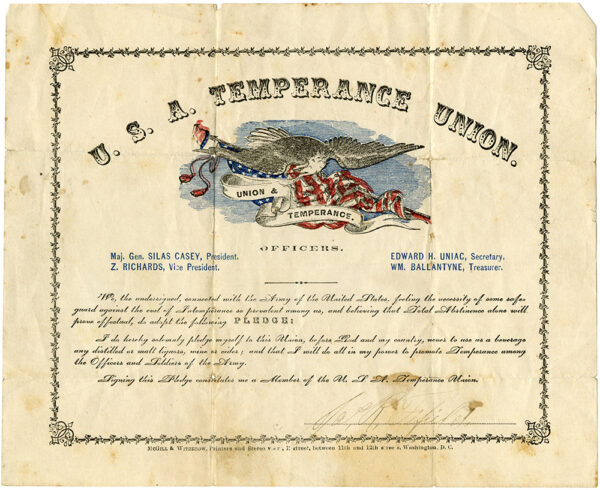

Courtesy of VCU Libraries Thompson Collection of Lincolniana

Courtesy of VCU Libraries Thompson Collection of LincolnianaA temperance pledge for Union army soldiers

Megan Bever: Well, northern temperance reformers, you have the American Temperance Union, which is the big organization in the United States, and they lose a lot of members with secession. But their efforts during the war are multi-pronged. They send a lot of tracts and reading material. And the subject of those really run the gamut from, you know, you should worry about your soul, you don’t want to die a sinner, the very practical drinking will kill you, so don’t do it. Right? Any kind of approach they could get that they think might appeal to young men, they try to use it. They try to get guys to sign the pledge before they ever leave. They’re really worried that once they get away from their families they’re going to drink unless they’ve made that commitment to stay sober before they ever leave. They’re also working at the top, trying to get Congress to get liquor rations out of the military. And they don’t have much success.

So they have a multi-pronged approach. This let’s convert the soldiers individually, appeal to their morality or their pragmatism, but also working to prohibit liquor rations. About 10 percent of Union soldiers join a temperance organization. So that’s not a lot, but it’s about the same as what the temperance movement was getting in mainstream America. It’s about 10 percent of Americans who are part of the movement. So there’s some success. There are definitely soldiers who take pledges, who attend temperance meetings in camp, who try to get other men to stop drinking, who write home to their families when they’re really concerned that men are drinking too much, who are alcoholics essentially, is what we would say. They don’t describe it that way, but they get really concerned when their brothers and friends are drinking too much. So, there are efforts in and outside of the camps to try to reign that in.

Confederates don’t have anything as centralized as the American Temperance Union, but they’ve got tract societies and local organizations that are doing the same thing—trying to get men to sign pledges, sending reading materials, those sorts of efforts.

Terry Johnston: Well, yeah, and you mentioned in your book, a really nice scene about Union soldiers right before they’re getting ready to be mustered out and going home. They’re pledging their allegiance to temperance. And there seemed to be rather high hopes, at least among the temperance folks, that this was going to really carry over into the postwar years and really change American society at large. And that fizzles out.

Megan Bever: Yeah. It’s the way temperance reformers think about reacclimating veterans to American society, right? They’re going to bring them home, reincorporate them back into their families and create good, sober American men. And it doesn’t work. And temperance reformers, they’re hoping also to capitalize legislatively. The federal government grew during the war, so it looks like that this is going to be the time that they’re going to get legislative support for temperance and for prohibition. And that’s where they end up putting their efforts. And it takes 50 years, but they get national prohibition.

But for Civil War veterans, it doesn’t work. And I think that’s the really sad part of this story. These are men whose physical and emotional health is really broken by the war. And the state of 19th century medicine being what it is, they’re using liquor to self-medicate. Or even with the permission of their physician. And northern society really casts them aside. These veterans, they don’t live up to civilians’ hopes. They don’t reintegrate into their families for many reasons. Drinking is just one of those. But yeah, temperance reformers want a moral, sober society and Civil War veterans who’ve, in the case of the North, literally saved the country, they get pushed aside.

Terry Johnston: Yeah. Before we wrap up—and this is going back to another thing that used to regularly come up reading soldiers’ letters—the whole idea of a mixture of whiskey and gunpowder as some sort of supercharged way to get men ready for battle. You came across this as well, I’m guessing. Any idea how this got started?

Megan Bever: This is one of those things that shows up and it’s indirect. So, where I see it coming up is that soldiers from one side will accuse their counterparts on the other of not having any patriotism, so they have to mix gunpowder and whiskey together to fight. It’s this idea that their cause is so shoddy that they’ve got to make this like super drug to get them ready. I didn’t come across anyone actually making this kind of concoction for themselves, maybe for obvious reasons, like I don’t know how sick it would make someone, but it feels like it could be pretty devastating.

There’s some really interesting scholarly work being done on this larger relationship between using drugs to make soldiers fighting fit. And this is what the military is trying to do in the war with liquor rations and medicinal rations. They’re trying to make sure the soldiers are healthy in their own way. But the gunpowder-whiskey thing, I don’t know where it originates, but it seems to be like an insult almost that gets hurled at soldiers from the other side. But it’s really fascinating.

Terry Johnston: It is, and I think you’re right. I think that’s the reason it’s happening, that they’re trying to find a way to reason out why the enemy fought so ferociously. I could be wrong about this, but I believe you see this as early as First Bull Run, where right out of the gate soldiers are already using that as a way to explain the enemy’s ferocity.

Megan Bever: And I would be curious—I don’t study earlier wars—but I would be curious to know if it comes up in the Mexican-American War or earlier wars as a way to explain some sort of enemy that’s supposedly inferior. My guess would be it has even a longer history possibly than the Civil War. Just any time where you’re using powder. My research doesn’t go back that far, so I’m only asking questions.

Terry Johnston: Well, if any of our listeners have an answer for us…

Megan Bever: That would be awesome.

Terry Johnston: …let us know. I think you’re probably right. It would be surprising if this were something that just popped up during the American Civil War and then went away. You would think that there’s some roots to it.

Well, Megan, before we wrap up, is there anything important you think we’ve left undiscussed on this subject?

Megan Bever: Um, that’s a really good question. It feels like it’s been a really thorough conversation. I find myself thinking about this book a lot, even though it’s done, just thinking about the ways that in American culture, we still think about drinking and its problems. Or just any kind of food or substances that we put in our body and the way that they shape our identity and our morality.

And I think it’s something that people can watch for in their everyday life. It’s not just something that happened in the Civil War and now it’s gone and it’s done. And sure, there are funny stories and those sorts of things. I don’t want to say it’s like the core of being American, but I think it’s one of those topics that’s really closely tied to our identity as Americans in the way that we think about our bodies in relation to the nation and to our service to the nation.

Megan L. Bever is associate professor of history at Missouri Southern State University and the author of At War with King Alcohol: Debating Drinking and Masculinity in the Civil War (2022).

Megan L. Bever is associate professor of history at Missouri Southern State University and the author of At War with King Alcohol: Debating Drinking and Masculinity in the Civil War (2022).