Historian Gordon Calhoun discusses the pioneering developments in naval warfare that occurred during the Civil War, from the rise of ironclads to the birth of the submarine.

Transcript

John Heckman: Gordon, thank you so much for coming on the podcast to talk about something that I need to be more informed on and maybe a lot of listeners do as well. And that is the navy during the Civil War. I greatly appreciate your time.

Gordon Calhoun: Well, thank you for having me.

John Heckman: I think this conversation is going to be interesting because when we think of the navy we may only think of a couple things that occurred during the American Civil War, or some people just like land battles better and we need to introduce them to something different. I think we should start right before the war, right at the beginning of the war. What’s the condition of the navy at the beginning of the Civil War?

Naval History and Heritage Command

Naval History and Heritage CommandA depiction of U.S Navy personnel in the 1850s

Gordon Calhoun: The condition of the navy is not bad. Some writers in the 1880s are going to look back and say, oh, we weren’t prepared. They were prepared for a different type of war. They were prepared for war with Great Britain. They have about 60 ships. They were building more. Isaac Toucey, Buchanan’s secretary of the navy, had a building program that was pretty impressive. He was the one that laid down and authorized several steam sloops and authorized the construction of several other designs of ships.

And so they were ready for a different type of war. They were ready for a blue ocean conflict with the European power or doing the typical peacetime duties that they had been doing for the last 40 years. Africa had been taken a bit more seriously. The slave trade patrols with the Africa Squadron were ramping up, mainly due to political pressure of the abolitionists having an effect in getting the U.S. Navy to do more to stop the international slave trade. Particularly because American merchant ships were the ones doing most of the trading by this point. We had an expedition out to bring the Japanese embassy from Japan to Washington, D.C. They arrived just at the right time to see our country falling apart. But they arrived to great pomp and circumstance to Washington, D.C. There’s a squadron out in the East Indies fighting pirates out there. And then we have a squadron down in Mexico, which that’s the “home squadron.”

And so when Fort Sumter happens, the U.S. Navy is nowhere in home waters and they weren’t going to be. A lot of historians have said, and even contemporary observers at the time, like, well, where’s the navy? Why didn’t they stop Fort Sumter? Because the navy is an external force. It is not meant for settling internal conflicts. And so its job is to be overseas and most of its active duty ships were overseas somewhere. Even the home squadron, the ships that were supposed to be based in the area, most of them were off of Vera Cruz, Mexico, looking after American citizens and property down there. They do get the message of, please get back here as fast as you can, something has happened at Fort Sumter, we need you to get back here. And Fort Sumter by that point had been settled and so most of them do return home, back to Norfolk, for what ends up being the burning of the Gosport shipyard. USS Cumberland, in particular, goes back to Norfolk to participate in the evacuation and the unfortunate scuttling of the yard itself and all the mistakes that were made there.

So what’s the navy doing? The navy is doing its job that it was assigned to do for the last 45 years. It then has to switch over to, oh, wait a minute, this is an internal conflict mode and start building ships meant for coastal purposes and river warfare purposes.

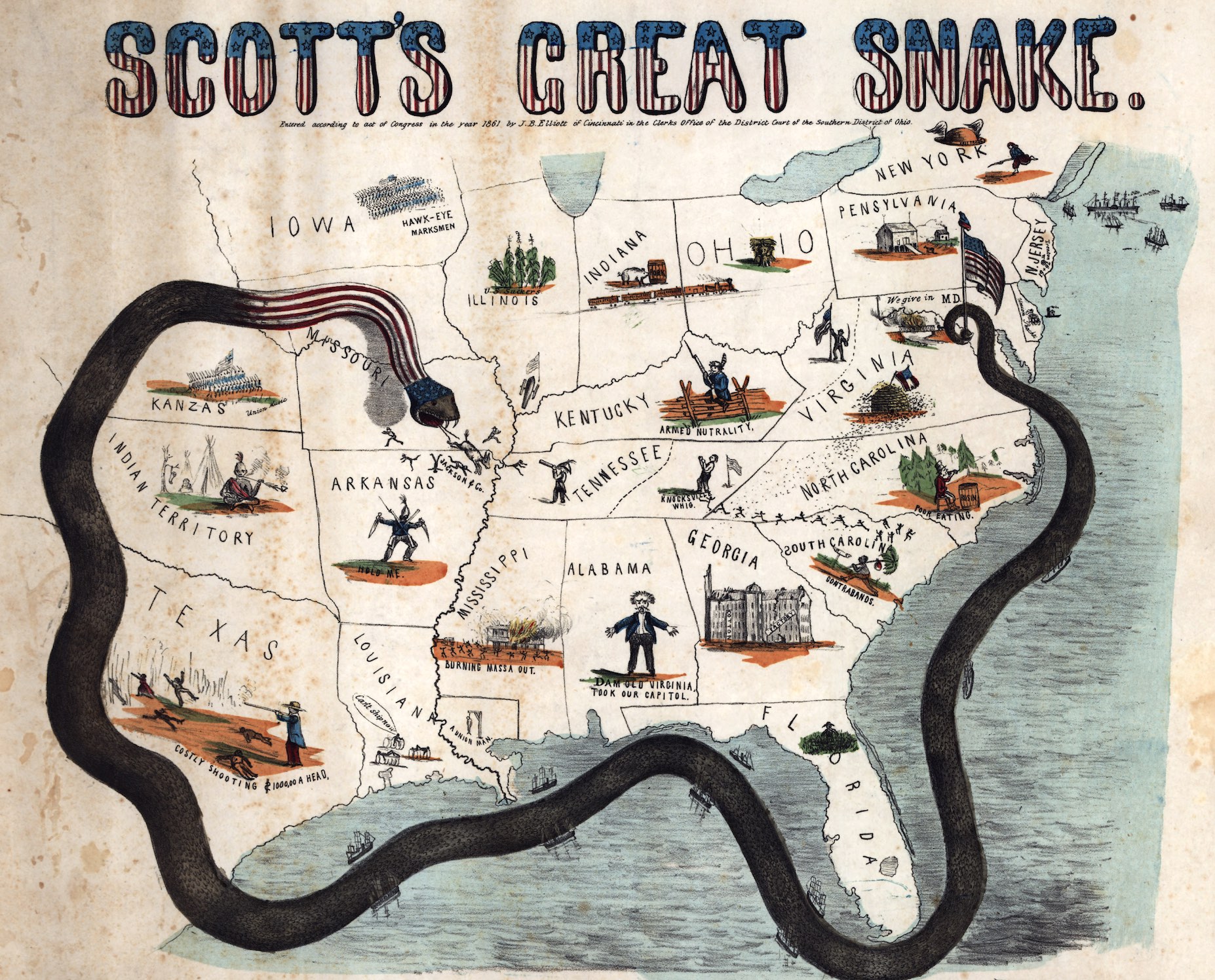

John Heckman: The Union military comes up with this plan, the Anaconda plan. And many of the listeners are going to know what that is as soon as we bring it up. How does that transition happen? Because you have this navy that’s thinking about the way we did things in the War of 1812. And now they’re transitioning into this idea of, you’ve got to be almost like a Coast Guard force with the Anaconda Plan, right? So what’s that blockade work like? How is that installed and how does that operate?

Gordon Calhoun: It doesn’t go well at first, because they need a lot of ships and they need a different type of ship. They had blue ocean ships meant for blue ocean operations. They did not have a good number of ships meant for coastal purposes to stop merchant ships. They were just not set up for that purpose. And so that’s why CSS Virginia has such big targets at the Battle of Hampton Roads in 1862 because there are not enough small warships to go around. So they are forced to blockade Hampton Roads with three sailing frigates—well Cumberland’s technically a sloop of war—and a steam frigate. They do not have small warships to operate inside this harbor. And Hampton Roads is one of the finest natural harbors in the world. Nonetheless, only half of it is navigable for big ships.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressThis illustration depicts the Anaconda Plan, the Union strategy devised by General-in-Chief Winfield Scott at the start of the Civil War to defeat the Confederacy by a naval blockade of its ports.

And so they do start this crash program—and a very successful program—of building small warships. They build what are labeled the 90-day gunboats, even though they take longer, but it sells well in the newspapers. They’re cheaply made. They’re lightly armed. And that’s all you need. You don’t need big warships to try to chase down what are first just merchant ships carrying Confederate goods in and out. But then eventually the merchants in England and the merchants in the Confederacy get smarter about this and start designing and procuring blockade runners, ships that are specifically built to run the blockade. And the U.S. Navy has to respond with an equal number of small ships.

Plus they recognized very early on in the blockade that, yes, they’re going to have to blockade ports like Norfolk, Wilmington, and Charleston. But they also are going to have to go after little places with little ports, like in Cape Hatteras, like in Florida, like little coastal areas in Georgia. And, ultimately, they’re going to have to learn to work with the army and the army’s going to have to learn to work with them, that the best way to establish a blockade is to park 5,000 Union soldiers in the port, just occupy the port.

And the navy’s greatest achievement early on is the capture of New Orleans. It is a battle that is not fully appreciated. That is the second largest city in, actually, it might be the largest city in the South, New Orleans is. And they capture it without army help. Farragut is able to run past the forts with its fleet and then park his guns right off the coast, off the shorelines of New Orleans. And they surrender, through many mistakes. Which way was the offensive coming from? Was it coming from the north, coming from the south? But what the navy did to capture New Orleans is an underappreciated victory, an underappreciated achievement, for capturing a city that large early on in the war. And that basically shuts off the entire Mississippi River for any kind of access for blockade running. And most of the blockade running has to be done through Texas, which they do very successfully, through Galveston and Brownsville. And then later in Mobile as well.

John Heckman: You brought up this idea of the navy working alongside the army. Is this the early days of that evolution of the combined arms, where they’re trying to work together?

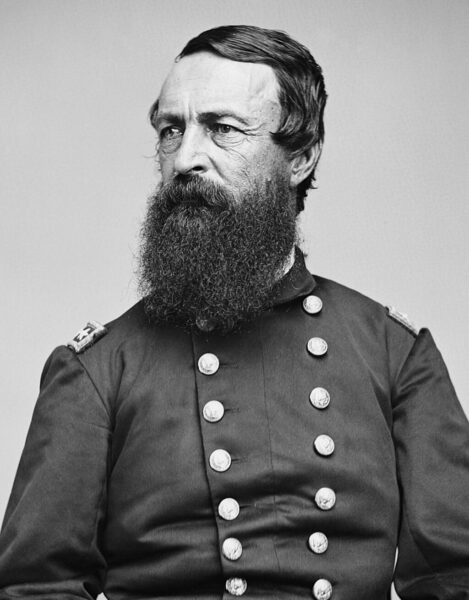

Library of Congress

Library of CongressDavid Dixon Porter

Gordon Calhoun: They’re trying, and they’re two different wars happening here. Out west they work wonderfully, because it’s Grant and Porter. Up in the northern offensive that starts in Cairo, Illinois, and proceeds ultimately to Vicksburg, the army and the navy get along very well. In particular, David Dixon Porter, and a young General Grant get along very well. They understand they need each other, and that’s one of the reasons they’re able to capture Vicksburg.

In the East, it’s much different. There’s a completely different war happening in, say, Virginia. Do you have a squadron of ships that are not necessarily meant to fight in the rivers? Eventually they do get them. They even procure Staten Island ferry boats to work the James River. And the army and the navy are not on very good terms. And of course, the biggest disaster of them all is Charleston. [John] Dahlgren, or [Samuel Francis] DuPont before him, never, ever get along with Quincy Gilmore, never get along with each other at all. And Charleston is probably one of the great embarrassments for the navy. And they knew it was an embarrassment. Here it is, the heart of the Confederacy, where the rebellion started, and we can’t capture this fort. We can’t capture this city. What is the problem here? Well, the problem was that they didn’t follow what the British did in 1780, which is don’t go by sea, go by land. But the fact that the army and the navy just kept blaming each other is one of the great mistakes and embarrassment for the fleet.

John Heckman: When you go around and speak with people about Civil War naval history, do you hear some similar things that I had heard, where people talk about the Battle of Hampton Roads and they talk about CSS Virginia and USS Monitor and they say, oh, these are the first ships in the world to be covered in steel, or iron. Do you have to break it to them sometimes that, hey, this isn’t actually the first. There were some in Europe that were developed that we need to think about too?

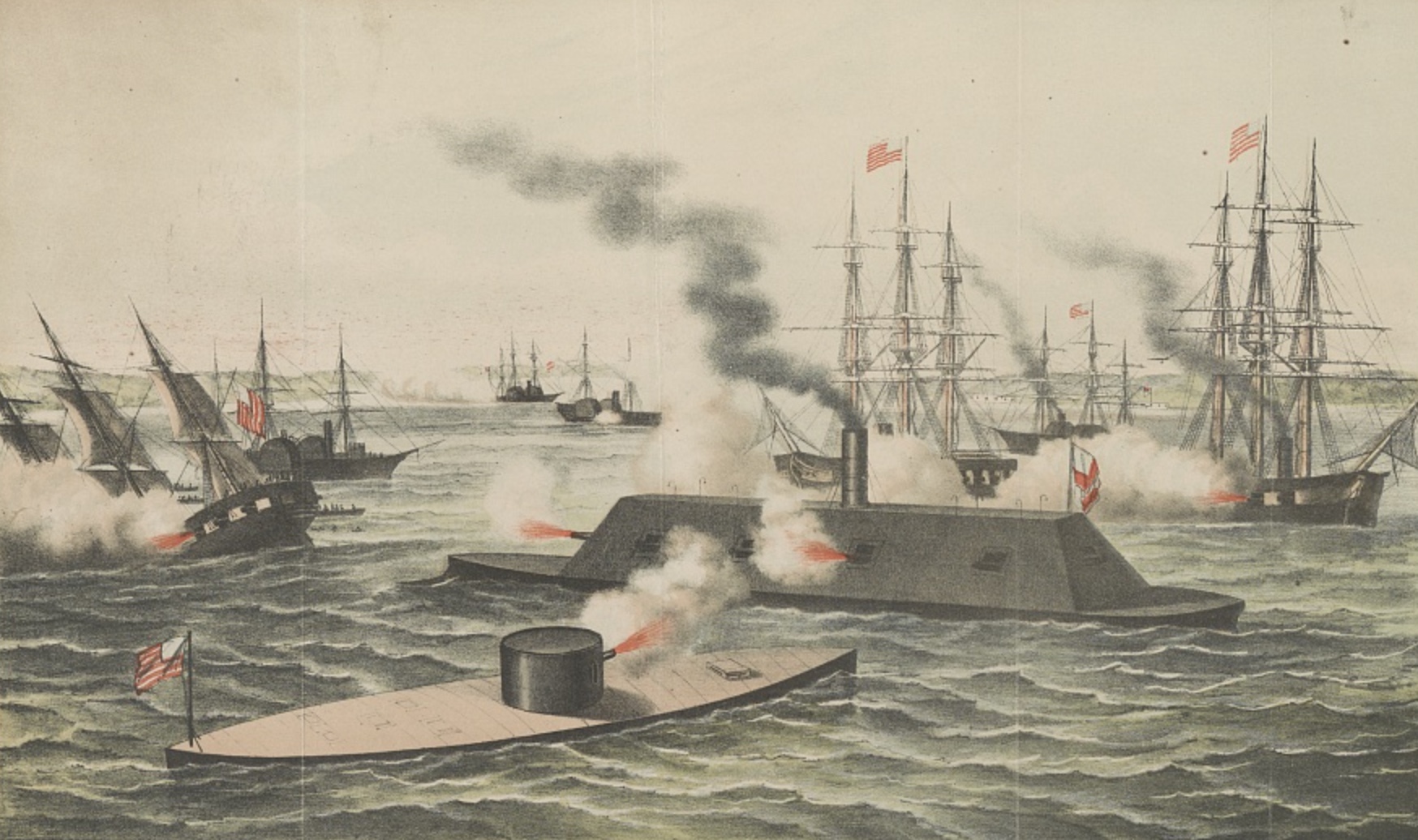

Gordon Calhoun: We do. We do have to go the “actually, uh,” that yes, the Gloire and Warrior were first in iron, that they were the first ones to do iron. And even the vaunted turret of the Monitor, [John] Ericsson did not invent. That was a British guy who invented the turret, which Ericsson had to pay royalties on. But Monitor is still an amazing invention. It’s an amazing work of art, what Ericsson did to get all these technologies to work together. And the fact that they built it so fast, and it is an incredible story of how they got it from New York City, down from Brooklyn, down to Hampton Roads just in time. I mean, it sets up for a Hollywood movie. The Cumberland and the Congress are destroyed. The U.S. Navy needs a savior, and oh, lo and behold, here comes our white knight. That night the Monitor arrives to save the USS Minnesota. I mean it works out perfectly.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressThe Battle of Hampton Roads

So I do have to break it to them, but I also recognize their appreciation of the warship itself. And the same with Virginia as well. That the Confederates had to be innovative. They were lacking proper infrastructure. And they came up with this warship, which becomes the model for all Confederate ironclads going forward. But, yeah, I do have to break it to them about that. But I also then go further and say the USS Monitor’s not the only one. They wanted to have something in the order of 50 more monitor-type warships after that. And they didn’t get them for various reasons. There’s a whole study about how the monitor program was a failure in systems engineering, but they did build several more of them.

John Heckman: How was the Battle of Hampton Roads seen by the people? Was that seen as this defining moment of the war where now we’re seeing something that is foreign to Americans. This is completely different. It’s like they’re on Mars right now?

Gordon Calhoun: They’re perceiving the moment that they stopped the Confederates, that Monitor saved the U.S. Navy. Because there were some hysterics about what happened on March 8 about Cumberland and the Congress being sunk. They were going nuts that Virginia was going to come up the Potomac River and attack Washington. And so when Monitor does stop Virginia from sinking the USS Minnesota—and I am of the side that Monitor won the battle, in case people want to know, because her mission was to save the Minnesota, which was one the magnificently built steam frigates and the flagship of the North Atlantic Squadron—the newspapers hailed that, that they were able to stop this Confederate monster. And then the Monitor people ride that publicity wave, because it wasn’t the only ironclad design proposed. There were two others, the Galena and the New Ironsides. And the New Ironsides probably was the better design. It was a more simple design, more practical, had more firepower. But they only built one of it, partially because of the positive publicity coming out of the March 9 battle, that everyone’s like, oh, we got to have more of these things.

And each ship had flaws. Monitor only has two guns, and they take five to seven minutes to load. New Ironsides is coming in with 16 guns. New Ironsides has a four-inch solid plate, which got hit 50 times by Confederate forts and remained on station. New Ironsides got hit by a torpedo by the CSS David underwater and was able to remain on station. New Ironsides looks like a big bathtub. It’s an ugly creature. And people in Philadelphia are very proud of the New Ironsides compared to the Monitor, which is a New York construction. And it is also partially politics. The New York politicians were able to convince the navy of no, no, go with this monitor concept, you don’t need that.

John Heckman: Does that two-gun system on the Monitor redefine the idea of firepower, or placing your firepower on a position?

Library of Congress

Library of CongressJohn Dahlgren standing next to a Dahlgren rifle in 1865.

Gordon Calhoun: The Dahlgren gun allows the navy to have fewer guns per ship. The Cumberland, when it was designed, was originally designed in the same lines of the war of 1812 frigate. It was going to have 50 guns. But with the Dahlgren system, they were able to cut the number of guns down to 22. And 22 guns means less men, costs less, and also produces more firepower. An 11-inch Dahlgren is shooting out a 150-pound shell. The biggest of the War of 1812 cannons is the 32-pound carronade. well, there’s also a 42-pound gun, the Long Tom, that one privateer uses, but it’s an impractical size. With Dahlgren’s gun, you’re able to have more firepower with less people, and so they’re already trending in the direction of fewer guns. Fewer, more powerful guns. And then with the 11-inch Dahlgren, that is actually one of the newer technologies that Monitor deploys. The Cumberland and other wooden ships had 9- and 10-inch guns, and Dahlgren builds this 11. And that’s actually one of the controversies of the battle is that they didn’t use a full charge, a full 30-pound gunpowder charge on the 11-inch Dahlgrens, they only used a 15. And that was by instruction, because they hadn’t fully proofed the gun yet.

So not only did they go into combat, the Monitor, go in the combat with this revolutionary turret, they also went into combat with a brand-new gun as well. And Dahlgren was a very vain man. Dahlgren was convinced, well, if you did a full charge, you know, you could have defeated the Virginia. And Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox is asked by Congress, well, how are you going to beat these Confederate ironclads? And his short answer was, we’re going to build a bigger gun. And he tells Dahlgren, build a bigger gun. Dahlgren, being the proud man he was, says, I don’t need to if they just used it correctly. And Fox insists, you know, build a bigger gun. And so they built a 15-inch Dahlgren and just as a vanity project, Dahlgren built a 20-inch Dahlgren, which is the biggest gun of the war, which is never actually used. He just built that as a vanity project. And there are only like four of them built, and each one of them had a name, like named after some demon. But the 15-inch Dahlgren does successfully put a shot through Confederate ironclads. It is a successful gun. And Fox in the end was correct. If they just built a bigger gun, we could put a shot through these Confederate ironclads.

John Heckman: Well, since we’re on the subject of size, we need to talk about the size of the navy at this time. You said something to me earlier when we were offline that I had not known, that this navy is the biggest one the U.S. has until the Second World War. That’s massive.

Gordon Calhoun: Yes. It is massive, and the number of men required is in the tens of thousands, which is paltry compared to what the army’s producing. But it does require a different skill set to be a sailor, especially among the junior officers. It’s not like the militia, where you can give someone a gun, give them training, and throw them out on the battlefield. It does require an immense amount of teamwork. And this is a theme we produce even for the modern navy. You can build the ships, but you still need to have the sailors to go with it.

So when they do get up to somewhere in the several hundreds of ships, the navy realizes that they’re going to need more officers. And the Naval Academy has only been around for just about 15 years. And so they go to the merchant marine and ask for volunteers. And they get several hundred of merchant marine officers who have 20 to 30 years of experience at sea. Some in the Arctic Ocean, in the South Pacific because they’re whale ship captains. And the navy is able to tap into this resource of gentlemen who already know how to handle a ship. All they need to know how to do is take orders, which was always a sore subject between career men and the volunteer officers. But eventually they got along and it’s a remarkable story in itself.

One of the high school ways of approaching the Civil War is the advantages and disadvantages that North and South had. One of the big advantages the United States had in the war was its experience of merchant marine. It’s particularly out of New England and New York. The South did not have that kind of tradition. They had some, but New England, especially the new Bedford whaling community, provided at least a hundred junior officers to captain these small warships off the coast of the blockade. And every one of them were volunteers. And many of them do very well in combat. And the navy could not have functioned without them.

John Heckman: When our listeners are reading information about the navies during the Civil War, and they come across that term torpedo, what should they be thinking about? Because some people have come up to me and they’re like, I didn’t realize that we were firing torpedoes in the Civil War. And I’m like, okay, we need to have a discussion about what a torpedo is. But you can describe it better than I.

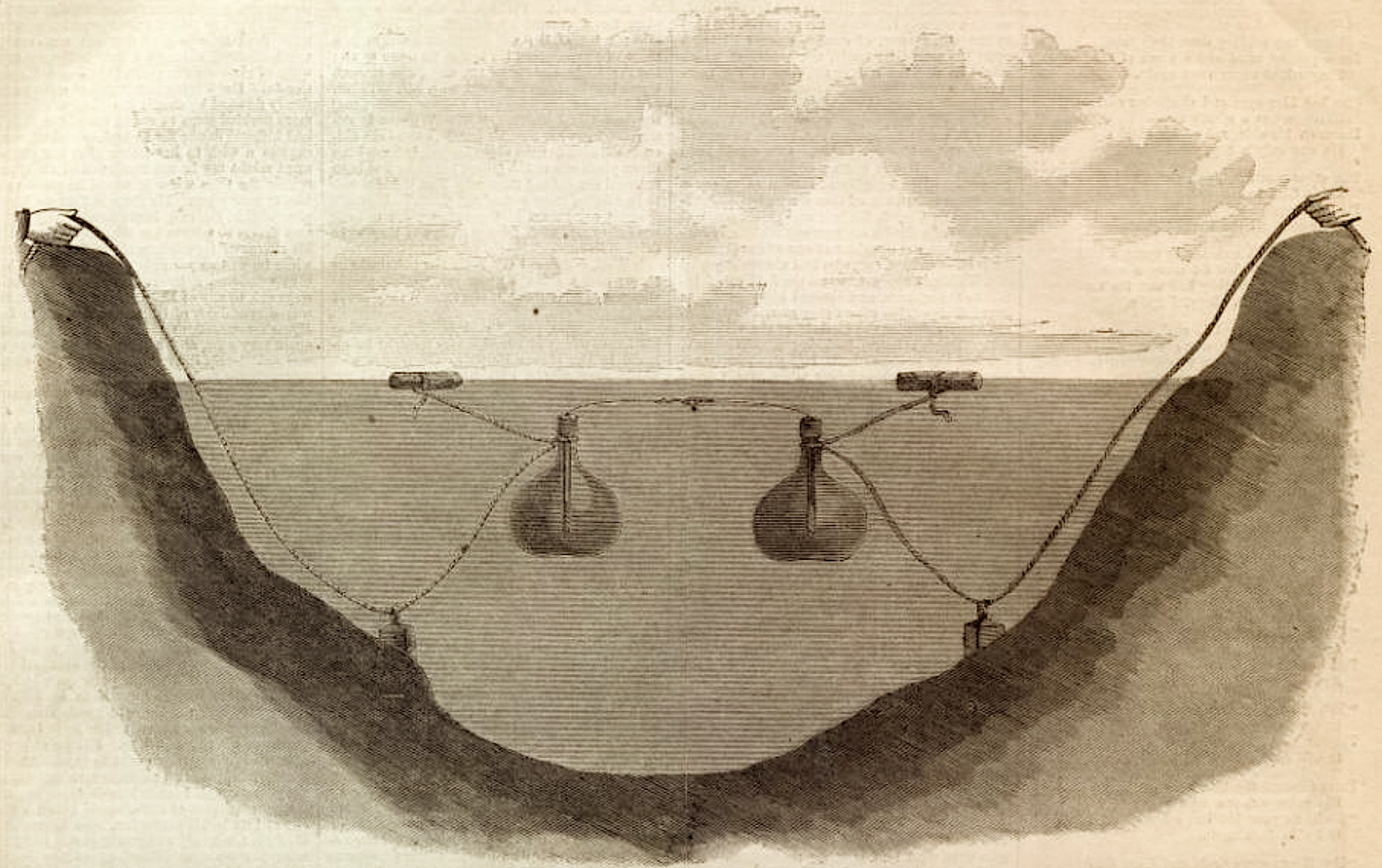

Gordon Calhoun: Well, the fun fact that I learned about torpedoes just within the last year is where the term comes from. The term comes from a stingray. The scientific name of certain stingrays is torpedo. And the inventor, Robert Fulton, the man who invented some steam warships and invented several other things in the early 19th century, he came up with this term of, well, we’re going to have an underwater explosive. What kind of creature zaps people underwater? A stingray does. And so he took the scientific name off of that and called it a torpedo. So that’s why the term for underwater mines is torpedoes. Now, what submarines shoot today are called technically a locomotive torpedo. the practical designs come out in the 1890s with a Whitehead torpedo. And then United States invents the Howell torpedo, but everyone copies the British. The Whitehead torpedo becomes the standard design for locomotive torpedoes. They’re all modeled after that, even to this day.

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyA depiction of Civil War torpedoes from Harper’s Weekly.

When Farragut says “Damn the torpedoes,” he’s talking about undersea mines that the Confederates very efficiently deployed. That was their number one weapon against the U.S. Navy. It was not ironclads, it was not forts. It was these, what some people called infernal machines, whether they were just a barrel of black powder, where there was an operative on shore ready to detonate it with an electric charge. They placed them everywhere. They placed them on the James River, they placed them in Charleston. They placed them in the Mississippi River. And that is the number one opponent of U.S. Navy ironclads. The Cairo on the Mississippi River, which the National Park Service has a very good display of, was sunk by a torpedo. The USS Tecumseh, the monitor that was sunk by a torpedo in the Battle of Mobile Bay.

What’s interesting about Farragut’s expression, “Damn the torpedoes,” you know, damn them all you want, they’re still there. And the Tecumsah hit it and goes down. And there are accounts from sailors who were down below, working the lower decks during the Battle of Mobile Bay, that they did hear torpedoes hit the side of the hull and didn’t go off. Captain [Percival] Drayton, Farragut’s chief of staff, would later write an appreciation for those sailors that worked down below, recognizing that if a torpedo did go off, they would be the first to take it. That he, working up top, would probably survive. But his men down below would be the first to take it.

And they did come up with some methods to try to sweep it. But the best way to sweep it was what they started doing in the Mississippi River, which is the number one role of any sailor to this day, and that’s to have someone on watch with a good pair of eyes going, Hey, that’s an explosive there. There it is. There’s a torpedo in the river. There’s a torpedo off our bow there. And that’s the number one job of any sailor, whether it’s 18th century or 21st century is the standing watch with a good pair of binoculars.

John Heckman: The other thing that people think about when they think about torpedoes, incorrectly as far as the one that swims through the water, is submarine warfare. And obviously we got to bring up the Hunley because we’re starting to consider new ways of warfare at this time. And it’s not the first sub, but it’s the first one to sink a ship in war. What were some of the lessons learned from that, as far as, how can we take this, move it forward? Or was the idea kind of scoffed at after the war for a little while? Were they like, well, it worked, but yet it didn’t.

American Civil War Museum

American Civil War MuseumConrad Wise Chapman’s depiction of the Confederate submarine Hunley.

Gordon Calhoun: It worked. And then there’s some people that tinker around with it. It’s like the Monitor in that there’s still some technologies that have yet to be discovered to make it really practical. The locomotive torpedo makes submarines really practical later on. That gives submarines a proper weapon they actually could shoot from underwater. The case of the Hunley, it’s got a big, what they call a spar torpedo. Basically a big explosive on the end of a stick. And then you either ram it, or in the case of what the Cushing did to CSS Albemarle, you run up to the ironclad and then pull a string and then the bomb goes off. And it’s a very, very dangerous way to do it. And so the locomotive torpedo does make the submarine practical. Until that happens, it’s still a weapon that people are tinkering around with.

And, also, the submarine becomes a weapon for smaller navies, ones that do not have all the resources or the political will to build a big navy. And that’s the way submarines are seen. If you are a serious navy, up until about World War I, you built only big surface warships. World War I is when they really start to take the submarine truly seriously because of what the Germans were able to do to the British and American merchant marine. But it was a novelty. Now, the Confederates had to get innovative. They knew they were outnumbered greatly. They were outnumbered 20 to one in terms of ships. But then again, they were on the defensive and the burden of winning this war was on the U.S. Navy, not on the Confederates. So that’s why the U.S. Navy needed war ships.

John Heckman: What lessons were learned by the U.S. Navy about naval tactics or naval doctrine from this conflict?

Gordon Calhoun: Some people would say they didn’t learn anything, that it was just a one-off thing. That we don’t do blockades. That’s not the way you prosecute a war. I think they should have learned, and they will come back to this every so often, about the need for small warships. That you’re going to need a navy for littoral purposes. And every once in a while, the navy does create a riverine squadron. They created it for Vietnam. They even created one for the operations in Iraq. The term “monitor” actually gets used to describe some warships serving on the Mekong River in Vietnam. They are called monitors, and that is now a worldwide term for any ship with a turret meant for coastal littoral purposes.

I think some of the lessons also learned was that technology is important. That putting resources into research and development is important. The 1870s, they go back, they don’t learn any lessons. They decommissioned about 90% of the fleet. Because they don’t think they’re going to have any problems with anybody else and they just go back to the way they were operating in the 1850s. It isn’t until the 1880s we start changing politically that, oh, maybe we should be a global power. Then they start putting money into research and development, into steel warships as opposed to iron warships. The age of iron lasts all of about 10 years. Steel-hulled ships are starting to come online as early as 1864. The British start inventing a blockade runner called the Banshee, which has a steel hull as opposed to an iron hull or a wooden hull. The Confederate owners, when they first took it across the North Atlantic, thought it was so flimsy, it was going to break in half before they even got to where they were supposed to be going. But it is quite the invention. And then it gets captured. And so USS Banshee, here’s a little trivia, the first steel warship of the U.S. Navy was the USS Banshee. Most people will say no, it’s a A, B, C, D ship. But oh no. If you want to get really, really technical, the USS Banshee, with its steel hull, is the first steel-hulled warship in the U.S. Navy. And we’re not capable of reproducing it. We do not have the infrastructure to build steel worships until the late 1880s.

John Heckman: So, final question for you, Gordon, is one that I’ve fielded a couple times and I can’t answer because I’m a land guy and, sorry, that’s just the way it is. My people were ground pounders as they would say. But I’ve had people ask me, you know, I would love to read something about a person or a ship from the American Civil War because I don’t know enough about navy things. How would you field that question? What would you say to them about a personality maybe they could read about or a ship that really is a good introduction to what Civil War naval combat is like?

Naval History and Heritage Command

Naval History and Heritage CommandWilliam Cushing

Gordon Calhoun: The fun one to read is Lincoln’s Commando about William Cushing. William Cushing is an amazing personality. He is a rock star of the navy at the time. Some people say he is the patron saint of the Seals because that’s what he did. He was wounded several times. Not only did he sink the CSS Albermarle, but he also participated in the Battle of Fort Fisher, where he was wounded. He participated in campaigns around Virginia, the James River, and the Battle of Suffolk. The book is written in the 1960s. It’s famous for a different reason. The author was the one who was part of the quiz show scandal. If you watch the movie Quiz Show, the author, played by Ralph Fiennes, wrote Lincoln’s Commando. The book itself is very good. It’s a very readable book.

My colleague Anna Holloway, who used to be the curator at The Mariners’ Museum for Monitor, has a very good book called Our Little Monitor I would highly recommend. It’s both a technical history and an operational history of the warship. They go into some very technical details, which I personally love. I love the nerdy details. And then [James] McPherson, Professor McPherson, has turned out a one-volume history of the U.S. Navy in the Civil War, as have a couple other authors. And they do emphasize the United States Navy. They do not talk about the Confederate navy. Mainly because the U.S. Navy is the one doing most of the work. The Confederate navy is sitting around, waiting to get attacked. And the U.S. Navy has the burden of victory on it, so it’s doing the most operations.

About the Guest

Gordon Calhoun is a historian at the Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington, D.C.

Gordon Calhoun is a historian at the Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington, D.C.

Additional Resources

-

- The Anaconda Plan

- Battle of Hampton Roads

- Dahlgren guns

- Charles Van Doren, Lincoln’s Commando: The Biography of Commander William B. Crushing, U.S. Navy

- Anna Gibson Holloway and Jonathan W. White, Our Little Monitor: The Greatest Invention of the Civil War

- James M. McPherson, War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865