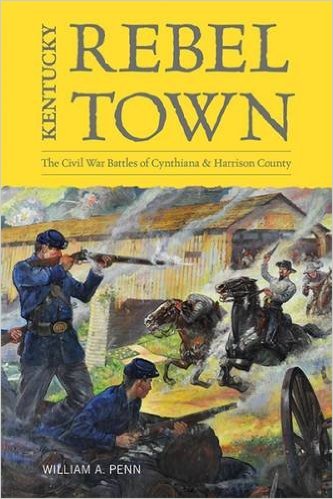

Kentucky Rebel Town: The Civil War Battles of Cynthiana & Harrison County by William A. Penn. University Press of Kentucky, 2016. Cloth, IBSN: 978-0813167718. $45.00.

William A. Penn’s examination of Civil War-era Cynthiana, or, as a local militia officer dubbed it, “that infernal hole of rebellion,” probes the divided loyalties and tense conflicts that wracked the picturesque Bluegrass town during four years of upheaval and turmoil (1). On trial is Cynthiana’s historical reputation as the Commonwealth’s “best rebel town,” a distinction that Penn challenges before ultimately reinforcing it, noting the county’s high-profile secessionists (such as State Representative Lucius Desha) and the large number of recruits that joined the Confederacy early in the war. Still, there is ample room for nuance, and Penn traces the local confrontations between Unionists and Rebels with aplomb, giving close attention to the shifting allegiances and fortunes of leading community figures. Thus, even as the town and county government came under pro-Union control by late-1861, sustained in office by an occupying federal force that avidly arrested disloyal citizens, Penn concludes that a majority of Cynthiana’s white citizens maintained their rebel sympathies throughout the war and far into its aftermath.

William A. Penn’s examination of Civil War-era Cynthiana, or, as a local militia officer dubbed it, “that infernal hole of rebellion,” probes the divided loyalties and tense conflicts that wracked the picturesque Bluegrass town during four years of upheaval and turmoil (1). On trial is Cynthiana’s historical reputation as the Commonwealth’s “best rebel town,” a distinction that Penn challenges before ultimately reinforcing it, noting the county’s high-profile secessionists (such as State Representative Lucius Desha) and the large number of recruits that joined the Confederacy early in the war. Still, there is ample room for nuance, and Penn traces the local confrontations between Unionists and Rebels with aplomb, giving close attention to the shifting allegiances and fortunes of leading community figures. Thus, even as the town and county government came under pro-Union control by late-1861, sustained in office by an occupying federal force that avidly arrested disloyal citizens, Penn concludes that a majority of Cynthiana’s white citizens maintained their rebel sympathies throughout the war and far into its aftermath.

The greatest strength of Penn’s work is the attention to military detail. Kentucky Rebel Town is, quite simply, the most complete and organized account of the Civil War in Harrison County. Without overstating the region’s importance in the larger conflict that was the Civil War—in the author’s words, Harrison County “played a minor military role” (278)—Penn examines topics ranging from enlistment and conscription to early confrontations over federal encampments around Cynthiana and the importance of John Hunt Morgan’s 1863 raid in revealing depth. There are few saccharine narratives in Kentucky Rebel Town, and petty jealousies and personal rivalries animate its central characters as much as grandiose claims to Southern honor or devotion to the Union. Within this framework, Penn maintains that events in Harrison County did lead to two important developments. First, Union control of crucial railroad bridges allowed troop and supply trains to operate efficiently. More significantly, Morgan’s Last Kentucky Raid ended calamitously in Cynthiana, and with it went the Confederacy’s best chance, as Morgan himself opined, “to hold Kentucky for months.” Although serious doubts remain as to the veracity of Morgan’s conclusion, Penn’s efforts to recreate the military struggle in Harrison County are a resounding success.

Harrison County’s civilian population also receives Penn’s attention, and he is at pains “to explore the effects of the war” on all local residents (4). The source material, in a place as divided as Cynthiana and the surrounding environs, is quite rich. Drawing from an impressive amount of letters, diaries, newspaper accounts, and federal records, Penn highlights the daily physical and psychological struggles that those on the home front endured and the shattering personal losses that were all too common during wartime. Importantly, Kentucky Rebel Town delves into the destruction of slavery in Harrison County, arguing that area whites, both pro-Union and rebel sympathizers, strongly opposed the emancipatory trajectory of the Civil War to the very end. Nonetheless, black enlistment steadily eroded the ability of slave owners to manipulate the enslaved, as nearly 400 ex-slaves from the county had joined the Union ranks by the end of the war. Despite these intriguing glances into life on the home front, however, Kentucky Rebel Town remains largely a military case study of events in Harrison County, and Penn rarely strays far from this stated objective for long.

The final chapter of Penn’s work offers a brief, insightful glimpse into the Civil War’s cultural significance and legacy in Harrison County. Strikingly, white Unionists and ex-Confederates appeared eager to put the conflagration in the past, even as old arguments and quarrels lingered in local newspapers and monuments were constructed to consecrate the dead and their sacrifices. Like many places in Kentucky, and across America, the Civil War entered the history books in Harrison County as a great struggle over “Constitutional Liberty,” the results of which entitled veterans on either side to the “respect and homage of all” (274-276). It was an interpretation of the conflict that was particularly appealing to many, even as it elided the county’s black population from the traditional narrative entirely. To the freedmen, after all, Cynthiana would never be Kentucky’s “best rebel town”—the 396 black Harrison Countians who joined the Union Army had already made sure of that.

Jacob A. Glover is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Kentucky. His dissertation examines everyday racial violence and the formation of black citizenship in the postbellum South.