Histories of photography in the Civil War era so often emphasize commercial, private photographic ventures—whether those of leading wartime luminaries who documented the Civil War through self-funded projects, or the varied patchwork of itinerant and studio photographers who flooded urban centers and military camps to offer portrait photographs of civilians and departing soldiers.

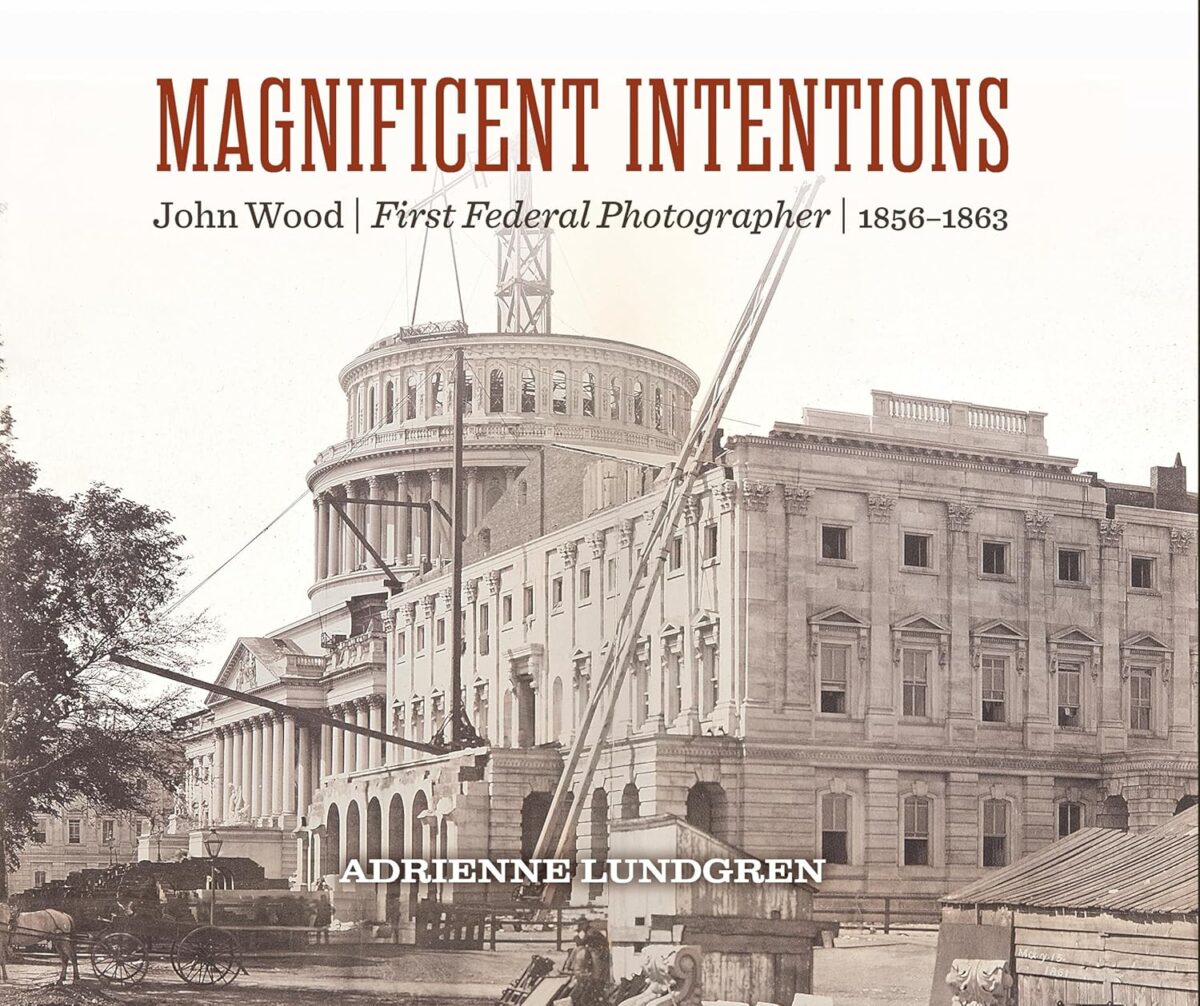

Adrienne Lundgren’s book-length treatment of John Wood, Magnificent Intentions: John Wood, First Federal Photographer (1856-1863), is the first of its kind and long overdue. Lundgren recovers John Wood’s prolific career as the first federal photographer for the United States. The book features more than 150 photographs chronicling the transformation of Washington, D.C., and which document the onset of the U.S. Civil War. Many of these photographs are unknown to either scholarly or public audiences, and their inclusion in Lundgren’s book will be well received by enthusiasts of the Civil War, American architecture, and the history of American photography. As Lundgren states, Wood was “in a unique position to capture the construction of the federal complex in Washington, D.C., during a period of radical transformation…As a professional photographer operating outside of the studio marketplace, his photographs and methods were unique among his peers.” Wood’s unique objectives, approach, and output, largely forgotten in histories of the era, receive their deserved treatment in Lundgren’s study.

As the Civil War and the wartime government drove and established many of the now-familiar pillars of the modern federal government, so too do we see the transformation of the built environment in a nascent Washington, D.C.—literally pillar by pillar—in the beautifully reproduced photographs that grace Lundgren’s book. The photographs by Wood cover the construction of long-familiar public buildings in Washington, like the U.S. Capitol and the Washington Aqueduct; some of the first panoramic photographs of the national capital; the first photograph of a presidential inauguration (James Buchanan’s in 1857); and documentary photographs of Civil War Washington and Wood’s photographic reproductions of military maps. Lundgren’s presentation of these photographs and her tracking of Wood’s trajectory as the first federal photographer establishes her subject’s pioneering work as foundational to the careers of later, better-remembered government photographers like Timothy O’Sullivan, whose photographs are an important element in our collective picturing of the Civil War and the American West.

Perhaps the most striking photographs to be included are those of the first inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln in March 1861. Importantly, Lundgren’s meticulous detective work identifies Wood as the photographer responsible for the surviving photographs of Lincoln’s inauguration, lending important context to the iconic moment on the brink of civil war as the president reminded audiences of the “mystic chords” that bound Americans together and expressed confidence that the “better angels of our nature” would once again guide the fortunes of the nation.

As Lundgren notes, much scholarship on the history of photography prioritizes artistic views (as well as the documentary lens lent by the camera), rather than the medium’s more industrialized applications. Here, her expertise as a photograph conservator shines, as does her focus on materiality and technique. The camera, hailed and celebrated as a tool for scientific recording and investigation that could provide visual transcriptions of reality since its earliest conception, was seized upon in a revolution in reprography and was used to achieve a level of accuracy in documentation unprecedented before the camera’s invention. The reproduction of maps during the conflict was important to enacting wartime strategy on both sides, although is often relegated to morass of Civil War minutiae. Meanwhile, Wood’s pioneering and painstaking methods are the focus in Lundgren’s illuminating section on photographic enlargement, with her prose allowing for an accessible and engaging exploration of little-known area of photographic innovation that allowed for the reproduction of photographs on an enlarged scale without noticeable loss of detail. (So too does a welcome appendix on wet and dry collodion processes and the ways in which they diverge provide a clear lesson in these often misunderstood and misrepresented processes). However, Lundgren’s book is not limited to exploring the practical or documentary realms of photography; nor does she not reduce these photographs to mere illustrations of historical events. Lundgren recognizes and emphasizes that photographs are as much statements about the world as they can be considered reflections or pieces of it, and these important pictures of democracy-in-the-making speak to American ambition, democracy, and culture in the Civil War era.

Ultimately, Adrienne Lundgren’s special expertise and perspective as senior photograph conservator at the Library of Congress and the focus of the book on John Wood’s unique and pioneering approach in the early decades of photography make this an exceptional work that tells a much-needed story about the Civil War era and the photographers who captured it visually. Lundgren’s celebration of Wood’s achievements and his technical skill in photography, as well as her chronicling of the rapid expansion of Washington, D.C., in the Civil War era, provides a remarkably fresh look at American visual culture during one of the most extraordinary and formative periods in United States history.

Dr. James Brookes is the Melanie Trent De Schutter Library Director at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture in Richmond.