Yale University Libraries

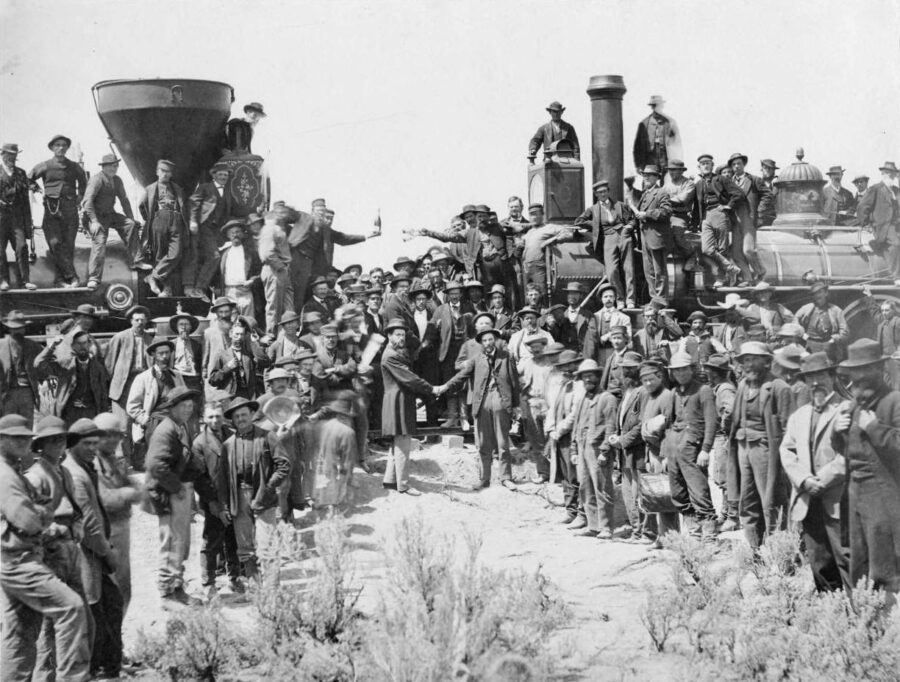

Yale University LibrariesA ceremony marks the completion of the transcontinental railway in 1869

In the midst of World War II, T.S. Eliot finished a series of poems that were collected in 1943 as Four Quartets. A prominent theme in the last poem, “Little Gidding,” is time and the place of humanity in history. In the penultimate stanza Eliot attests that “to make an end is to make a beginning. The end is where we start from.”1 In considering where to begin a series of essays on the Civil War and the American West, it seemed wise to follow Eliot’s sentiment—to begin at the end—and ponder how the monumental conflict that pitted North against South forever shaped the future of the prairies and plains, the mountains and valleys of the West. Civil War historians could begin at any number of endings, but here the date is April 14, 1865, and the place is the White House, where Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax has called on President Abraham Lincoln for a meeting.

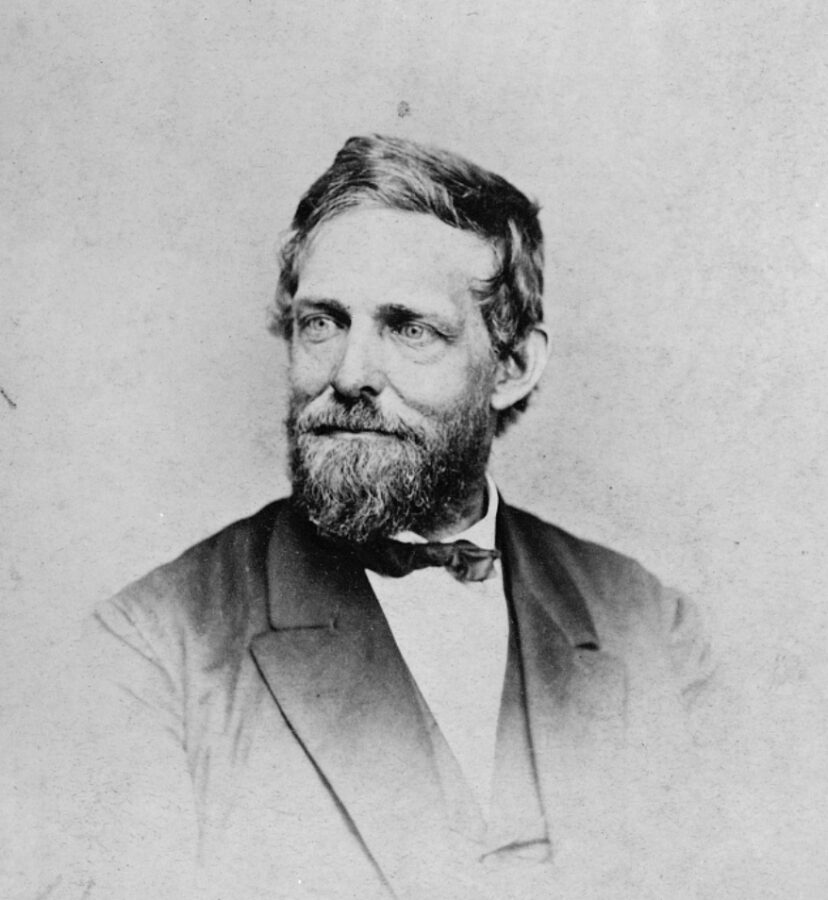

Colfax is perhaps best known to history for his involvement in the Crédit Mobilier scandal. That three-year-long fraud, from 1864-1867, involved prominent Republican politicians accepting bribes in exchange for promoting legislation favorable to the Union Pacific Railroad, and foreshadowed the rampant corruption of the Gilded Age. Beyond serving as a discouraging harbinger of growing political greed in the United States, Crédit Mobilier focused national attention on the most important American engineering project of the century: the transcontinental railroad. It should have come as no surprise that the first great political scandal after the Civil War originated in the West.

Lincoln gave serious consideration to the question of western settlement in his meeting with Colfax, which occurred in advance of Colfax’s planned trip across the country to California. The house speaker proposed a stop in the Rocky Mountains to inspect and report on the growth of the mining industry in Colorado Territory. Lincoln shared some remarks he hoped Colfax would pass on to miners and their families. It may have been the last speech Lincoln composed—by that evening, he was dying. Colfax, rather than depart the following day, remained in Washington, D.C., to participate in the public mourning that consumed the country in the weeks following Lincoln’s assassination.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressSchuyler Colfax

When he finally arrived in Colorado, Colfax did as Lincoln had asked: delivering the president’s remarks at a gathering of miners in Central City on May 29. “I want you to take a message from me to the miners whom you visit,” Lincoln had told Colfax. “I have very large ideas of the mineral wealth of our nation,” he went on. “I believe it practically inexhaustible. It abounds all over the western country, from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific, and its development has scarcely commenced.”

The American West offered solutions to several problems that confronted the victorious Union government in 1865. The two most pressing were the rising national debt and the question of military demobilization. Lincoln turned to the debt question first: “Now that the rebellion is overthrown, and we know pretty nearly the amount of our national debt, the more gold and silver we mine, we make the payment of that debt so much the easier.” Like many other Republicans of his time, Lincoln believed that the first order of business in the wake of the war was to reduce the vast bureaucracy developed during the conflict. The federal budget in 1860 had been $63 million. By the last year of the war that figure had increased to $1.3 billion. The debt from the Civil War exceeded $5 billion—and converting the West’s vast mineral wealth into currency represented a potential path to repayment.

In Lincoln’s view the West also represented a space for healing and opportunity, especially for the 1.2 million citizen-soldiers poised to shed their blue federal uniforms and return to their prewar pursuits. In territories such as Colorado, Lincoln believed, veterans could find useful and lucrative work. Lincoln feared that the rapid demobilization of the war’s volunteers might paralyze eastern industry, with not enough jobs available for every veteran who wanted work. But in the West, he believed, there was “room enough for all.”

Generations of historians and artists have depicted scenes like the one Lincoln imagined for his former soldiers—and the trope of the veteran heading west has been irresistible to filmmakers. In a twist that Lincoln would probably not have foreseen, nearly all the films in this genre focus on Confederate veterans, among them The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), The Searchers (1956), and The Long Riders (1980), which features a particularly memorable rendition of “I’m a Good Old Rebel,” arranged and performed by Ry Cooder. Dances With Wolves (1990) and Seraphim Falls (2006) feature Union veterans, though the latter emphasizes reconciliation between a Confederate colonel (played by Liam Neeson) and a Union soldier (Pierce Brosnan) after an extended cat-and-mouse chase across western Nevada.

In his Second Inaugural Address on March 4, 1865, Lincoln had urged Americans to work together to bind up the nation’s wounds. In the speech he handed to Colfax one month later, he suggested that the West might be a place where that healing could happen. And the prosperity that resulted in those remote territories, Lincoln concluded, would be “the prosperity of the nation.”2 Colorado’s miners and territorial officials gave Colfax an “enthusiastic and flattering” welcome, one member of the traveling party noted, and they listened to Lincoln’s words with “mournful interest and deep pleasure.”3

On July 3, 1991, President George H.W. Bush spoke at a ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of the completion of Mount Rushmore—the nation’s “Shrine of Democracy” in the Black Hills of South Dakota.4 There, Lincoln’s stony visage looms over a vast western tableau, alongside George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Theodore Roosevelt. Bush’s remarks offered a routine reading of American history, especially with reference to Lincoln. “Without Lincoln,” Bush explained, “I don’t believe we would be a whole nation today.”5 As he stood at the heart of the continent and addressed an audience of westerners, Bush mentioned his historic predecessor’s role in securing the passage of the Pacific Railroad Act—but insisted that the defining event of Lincoln’s presidency had little to do with developing the West, and all to do with saving the Union. Lincoln’s message to Colorado’s miners certainly suggests he held great affection and hope for the region beyond the 98th meridian, where the West begins.6

Cecily Zander is an assistant professor of History at Texas Woman’s University and a senior fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. She is the author of The Army under Fire: Antimilitarism in the Civil War Era (LSU Press, 2024).

Notes

1. T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets [coldbacon.com/poems/fq.html].

2. See the text of Lincoln’s remarks here: laphamsquarterly.org/climate/hidden-wealth; his remarks were later called forth by both sides in the late-19th-century debates over whether to allow the unlimited coinage of silver currency, or “free silver.” Americans have always wanted Lincoln on their side.

3. Samuel Bowles, Across the Continent: A Summer’s Journey to the Rocky Mountains, the Mormons, and the Pacific States, with Speaker Colfax(New York, 1865), 29.

4. The history of the land surrounding Mount Rushmore is complicated and contested. In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians that the land used for the memorial had been stolen from the Sioux, in violation of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The federal government awarded the Sioux $102 million as “just compensation” for the land, which the Sioux refused to accept as the nation continues to demand the outright return of the land.

5. George H.W. Bush, “Remarks at the Dedication Ceremony of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota,” The American Presidency Project [presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-the-dedication-ceremony-the-mount-rushmore-national-memorial-south-dakota].

6. Where the West begins if we are to accept historian Walter Prescott Webb’s definition, which suggests that environmental factors, in particular annual rainfall, begin to change drastically west of the line of longitude that runs just west of Austin, Texas, and east of Bismarck, North Dakota—forming the eastern terminus of the Great Plains. See Walter Prescott Webb, The Great Plains, Second Edition (Lincoln, 2022), 11–12.

Related topics: Abraham Lincoln