Courtesy of Rebecca Jo Plant

Courtesy of Rebecca Jo PlantRebecca Jo Plant (left) and Frances M. Clarke, winners of the 2024 Lincoln Prize.

Last year The American Civil War Museum (ACWM) presented its inaugural Lincoln Prize Lecture. The annual program takes place again this year on October 17, 2024, at their Tredegar site in Richmond.

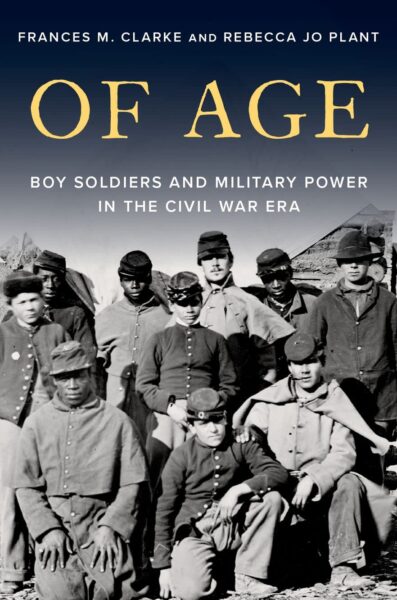

This year’s Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize was awarded to Frances M. Clarke, associate professor of history at The University of Sydney, and Rebecca Jo Plant, associate professor of history at the University of California, San Diego, for their book Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War Era—a topic they also wrote about for our Summer 2024 cover story, “Boy Soldiers.”

We asked them and ACWM’s President and CEO Rob Havers questions about the award process and the upcoming lecture and discussion. Their answers follow.

What’s it like to win the Lincoln Prize?

Frances M. Clarke & Rebecca Jo Plant: It’s been an amazing experience. Receiving the Lincoln Prize meant that our book automatically achieved a new level of attention—and not just from academics, but also from the large number of people who love to learn and read about the Civil War. It’s also led to wonderful opportunities, like delivering the annual Lincoln Prize Lecture at The American Civil War Museum in Richmond. Prior to publishing Of Age, we mainly shared our work at academic conferences and in professional journals and publications. It’s been rewarding to interact with a broader public audience that is interested in our findings and sharing their own family histories; one gentleman Rebecca spoke with whipped out his phone and pulled up an image of an ambrotype of his 16-year-old great-great-grandfather in his Confederate uniform. In short, we are just incredibly grateful for the boost that the Lincoln Prize has given the book and for the interactions we’ve had with people as a result.

What are the key lessons you hope readers will take away from Of Age?

FC/RP: First, we want people to recognize just how many underage boys served and how the military and society more broadly accepted and even celebrated their presence in the ranks. Second, by showing that underage enlistees constituted around 10 percent of the Union army, we hope to challenge the tendency to associate youth service only with the Confederacy. Third, we explain how Civil War–era Americans thought about young people’s capabilities, familial obligations, and their psychological and physical development in ways that differ dramatically from modern-day views. When it came to underage enlistment, people typically viewed the soldiers’ parents rather than the boys themselves as the injured parties, since they had been unjustly deprived of sons’ labor and services. Fourth, we uncover a traffic in young male bodies that emerged in the Union when bounties skyrocketed late in the war, rendering poor, immigrant, and African-American youths especially vulnerable to fraud and coerced enlistment.

Above all, we show how debates surrounding underage enlistment became conduits for larger questions concerning the centralization of federal and military power during the Civil War. This is especially clear in responses to the suspension of habeas corpus, which provoked outcry in part because it prevented parents and other relatives from seeking writs that would allow state and local judges to discharge soldiers if found to be underage or otherwise fraudulently enlisted. This ability to exercise local oversight of military enlistments reflected the history and logic of the United States’ decentralized, state-controlled militia system. Our book shows how this tradition was attenuated by two wartime transformations: first, the suspension and eventual federalization of habeas corpus, wherein local and state judges lost jurisdiction over federal detentions, including those relating to military service; and second, the rewriting of militia laws, which effectively transformed state militias into a subordinate arm of the U.S. military. As a result, the citizen-soldier tradition, which had been established to provide for local defense and to guard against the danger of centralized military power, was harnessed to forge a national army aimed at protecting the nation’s interest—preserving the Union.

What drew you to researching and writing about the service of boy soldiers?

FC/RP: It was actually not a topic that we set out to research! Frances had embarked on an entirely different project focused on how the Civil War changed Americans’ ideas about citizenship and their relationship to the federal government. She was researching a huge collection at the National Archives consisting of letters that relatives of Union soldiers sent to Washington, D.C., most of which consist of petitions for some kind of favor or assistance. Among these petitions is a sizeable subset of appeals from parents hoping to recover underage sons who had run off and enlisted without their consent. At first, Frances set all these letters from parents aside, reasoning that they concerned a very discrete issue and did not seem particularly promising: after all, everyone knew that boys sometimes snuck into the ranks during the Civil War. But the petitions from parents continued to nag at her, so she copied some and shared them with Rebecca, who had previously published works on the history of family relationships in the 20th-century United States. Long story short, Rebecca found the letters completely fascinating, and we ultimately agreed to pursue the topic together.

Are there lessons that we can glean from underaged Civil War soldiers’ service? Ones that might be applied today, as children are still serving in militaries around the world?

Are there lessons that we can glean from underaged Civil War soldiers’ service? Ones that might be applied today, as children are still serving in militaries around the world?

FC/RP: The issue is conceptualized very differently today. International discussions concerning child soldiers are now framed as a question of “children’s rights,” a notion that did not exist in 19th century. The United Nations’ Convention for the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), adopted in 1989 (and still not ratified by the United States), declared that states should “refrain from recruiting any person who has not attained the age of fifteen years into their armed forces.” Children’s rights advocates continued to push for a “straight-18” standard that would bar the use of youth below age 18 for any military purpose. In 2002, an Optional Protocol to the UNCRC moved closer to that goal, declaring that states should “ensure that members of their armed forces who have not attained the age of 18 years do not take a direct part in hostilities” and banning compulsory recruitment below that age.

It is entirely reasonable for rights advocates who want to shield the young from conflict to adopt this definition of a “child.” But the simple reality is that many youths of 15, 16, or 17, and some even younger, are incredibly capable. At the most fundamental level, this is why the problem persists. During the U.S. Civil War, some commentators even claimed that the youngest soldiers were the most daring of all, because they did not fear death or injury. And even boys who were too weak to carry weapons performed many necessary duties in camp. While the same is no doubt true today, this reality is somewhat obscured by a discourse that portrays “child soldiers” only as victim of exploitation. Such a framing may be politically necessary, but those who have studied child soldiers in different contexts around the globe suggest that it is much more complex phenomena on the ground.

One final thought: Although young combatants of course face the risk of physical harm, people today often emphasize the psychological trauma inflicted upon child soldiers. During the Civil War, Americans were far more preoccupied with what they saw as the unique physical vulnerabilities of young soldiers. Longitudinal studies based on veterans’ pensions records validate their concerns: as it turned out, the youngest Civil War enlistees (below age 18) were far more likely to suffer from long-term disabilities than the oldest (above age 30). It seems almost commonsensical that the young would suffer most from military service, but even so, cultural differences and historical context dramatically affect how people have conceptualized those dangers.

What’s next for you? Any Civil War-related projects in the works?

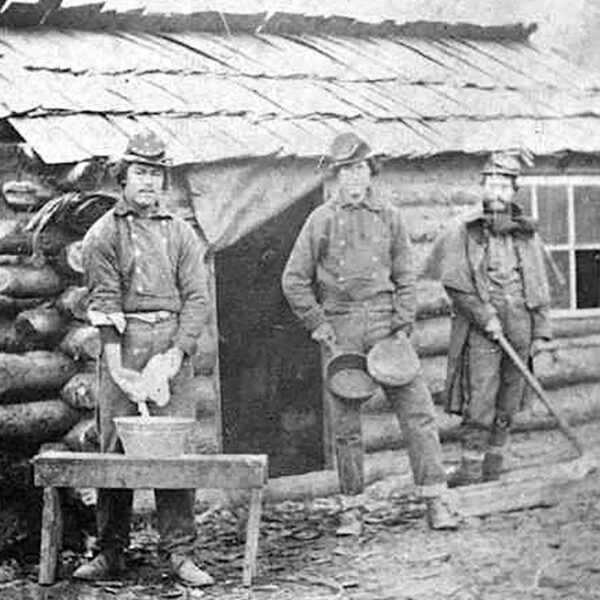

FC/RP: Big projects always leave a lot of unanswered questions. One of the questions that remained for us concerns some of the photographs reproduced in our book that picture African-American children serving as cooks or body servants to Union officers. The images are quite haunting, but our initial research turned up very little information about these boys. Their names almost never appear in primary sources, and scholars have yet to research their roles or experiences in depth. Together with Judy Giesberg, we’re currently looking at this cohort of young military laborers, hoping to provide more context and detail for making sense of these images. At the same time, the three of us have collected dozens of wartime court-martial records that focus on allegations of sexual encounters between underage enlistees and adult soldiers—a topic that we did not explore in Of Age. We simply ran out of time and space, so we’re hoping to fill in that gap with Judy’s help.

***

After last year’s inaugural Lincoln Prize Lecture, what changes, if any, did you make to this year’s program?

Rob Havers: Building on the success of last year, we will be keeping to the same format and are pleased to welcome Dr. Ed Ayers back again to lead the discussion with the authors and the question-and-answer session with the audience. We found that audience engagement was very well received and was a tremendous asset to the event.

John Dixon, American Civil War Museum

John Dixon, American Civil War MuseumACWM CEO Rob Havers addresses the attendees of the Lincoln Prize Lecture in 2023.

Will both authors be joining you at this year’s event, and can you give us a preview of what you will discuss?

RH: The 2024 ACWM Lincoln Prize Lecture is unique in that it will truly be an international event, as Frances Clarke will join us virtually from Sydney, Australia. Rebecca Plant will travel from California to join us in person at Tredegar, and both will present the lecture and participate in the discussion and audience interaction.

Discussing their 2024 Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize award winning book, Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War, Clarke and Plant will provide a fascinating overview of the 19th century perceptions of underage boys serving in the military. The authors will also explore the military, legal, political, and cultural perspectives on the service of underage boys in both the Confederate army and the Union army.

In line with our multi-year initiative “The Civil War and Remaking America,” the Lincoln Prize Lecture provides an opportunity for scholarly discussion on the significant ways in which the Civil War changed the nation we know today. In particular with this year’s ACWM Lincoln Prize Lecture one point of discussion will be challenges in the federal courts regarding underage boys serving in the military.

What other programs does The American Civil War Museum have planned in the coming months?

RH: As our audience and visitorship continue to grow, we are engaging creatively in presenting the history of the Civil War in a variety of ways to meet the interests of our visitors. We will continue our robust schedule of in-person and virtual Book Talks and also have a variety of additional programming planned. Events such as the annual Fall Festival at ACWM-Appomattox, the Tredegar Holiday Series, and of course our annual ACWM Symposium will be held in February with a very impressive slate of scholars discussing the course of the Civil War.

While I have you, can you discuss your recently opened exhibit, The Impending Crisis? How has the installation been received?

RH: The Impending Crisis exhibit continues to engage visitors from across the country, both online and in-person. Inspiring both conversation and questions, this exhibit explores the ways in which slavery caused the Civil War and provides a backdrop for a better understanding of the complex circumstances and opinions in pre-Civil War America. The Impending Crisis has enhanced the visitor experience at Tredegar by introducing a new element to the Civil War timeline.