It’s one of the great quotes, from one of the great documentaries, that sums up the legacy of the American Civil War:

Before the war, it was said ‘the United States are’—grammatically it was spoken that way and thought of as a collection of independent states. And after the war it was always ‘the United States is,’ as we say today without being self-conscious at all. And that sums up what the war accomplished. It made us an ‘is.’

Shelby Foote’s observation, so famously offered in Ken Burns’ documentary The Civil War, remains one of the quotable moments of that epic work because it speaks to what, I’m sure, Foote saw as a larger truth, that the war cemented the United States as a singular, permanent entity that transcended sectionalism and the disputes of the past. It’s a comfortable, reconciliatory view of the war and its aftermath, one that’s widely popular right down to the present. Indeed, it’s probably the dominant popular view of the war and its legacy.

But Foote’s anecdote is often taken literally, that the war caused a small-but-critical shift in the way people spoke and wrote about the United States as a nation, that Americans stopped referring to the United States as a plural noun, and started using it as a singular noun. It that actually true?

Not really.

On my own blog, I’ve demonstrated how Google Books can be insightful in tracking the use of specific phrases over time. It showed, for example, that the phrase “War of Northern Aggression,” often used today by those of a Southron frame of mind, actually sprang into common use in the 1950s and 1960s, concurrent with both opposition to the Civil Rights Movement and the Civil War Centennial. Although folks who use it today probably think of it as a term dating from the war itself, in fact it’s one that was coined new in their parents’ or grandparents’ day.

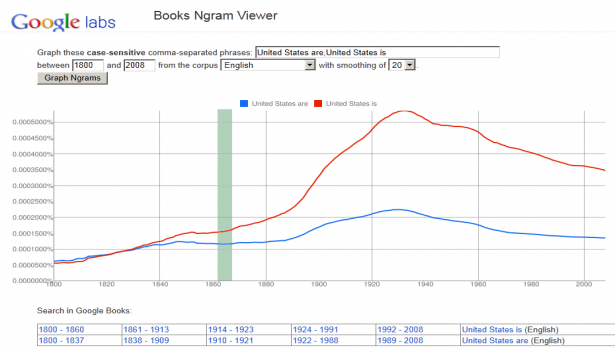

A similar search comparing the frequency of the phrases “United States are” and “United States is” reveals that, contrary to Foote’s assertion that the former was the preferred usage in the decades before the war, the two phrases were actually used about equally through the first few decades of the Republic. That began to change in the 1840s, when “United States is” (shown in red) began gradually to pull away from “United States are” (in blue) in printed usage. By the beginning of the war (shown here as a green bar), “United States is” was solidly more common in usage—though not greatly so—than “United States are”:

You can run these numbers yourself, here. Through the 1860s, 1870s and 1880s the usage of “United States is” increased steadily, and then faster from the 1890s into the 20th century. But “United States are,” while not the most common usage, has never dropped off into oblivion.

But as I say, Foote was speaking to a larger truth, as he saw it, about reconciliation in the wake of national tragedy. And in that sense, at least, the lesson embedded in his famous anecdote remains as valid today as when he told it 20-some some years ago. And that’s an indisputable truth.

Andy Hall is a Texan and Southerner by birth, residence and lineage, with a family tree full of butternuts. With a background in history, museum studies and marine archaeology, Hall also writes at his own blog, Dead Confederates.