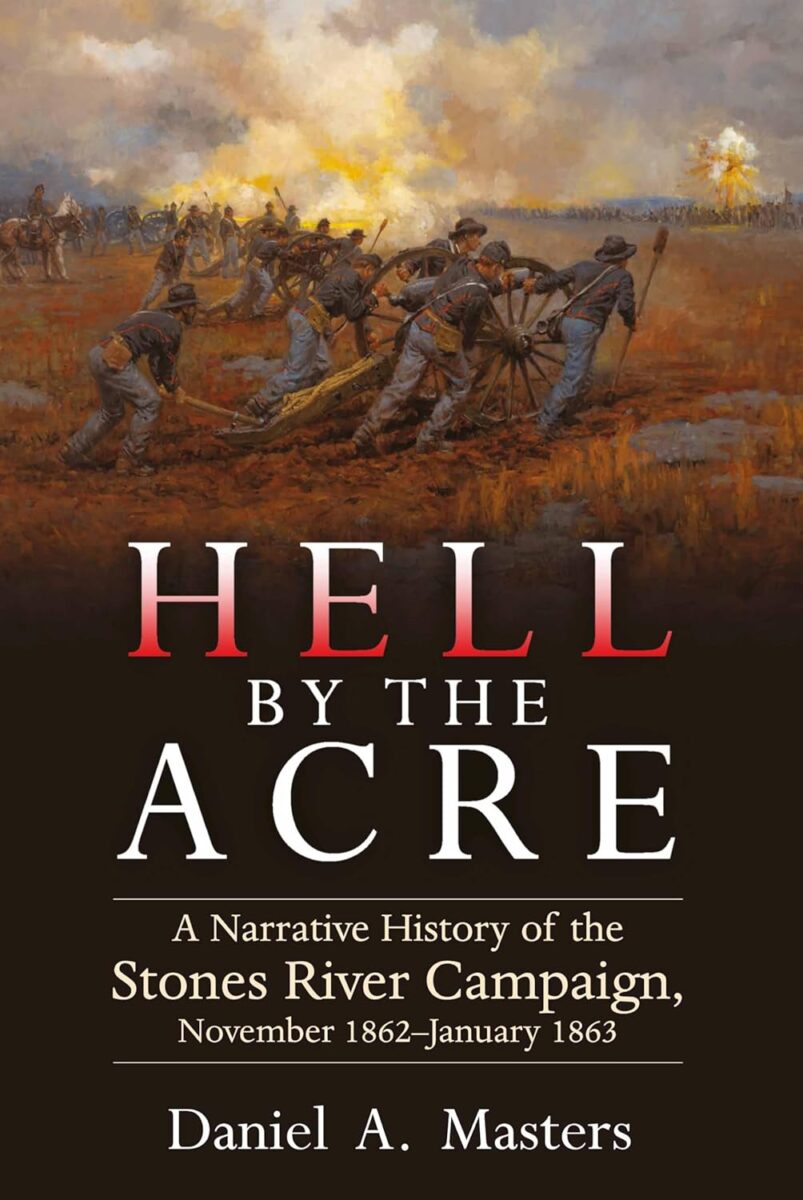

“Stones River,” observes David A. Powell in the foreword to this volume, “was a curious battle” (viii). It was a battle that saw the William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland on the operational offensive but Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee seizing the tactical initiative. Other battles surpassed Stones River in numbers of troops engaged and casualties suffered, yet it was one of the deadliest battles of the Civil War in the percentage of casualties inflicted—perhaps even deadlier than Gettysburg, depending on one’s figures (ix). The battle and its commanders are not the most intensely scrutinized among the Civil War pantheon, yet the harrowing Union victory amid the bleak winter of 1862-1863 came at a critical point for the U.S. war effort as the Emancipation Proclamation officially went into effect, earning the gratitude of the Great Emancipator himself. Historian Daniel Masters offers a new history of this curious and ferocious battle in Hell by the Acre, presenting a gritty, soldier’s-eye view of the struggle for Middle Tennessee.

Masters is perhaps best known for his blog, Dan Masters’ Civil War Chronicles, a platform that shares numerous fascinating and gripping firsthand Civil War accounts and reflects a most welcome appreciation for the war’s Western Theater. The Stones River Campaign, Masters observes, has generated only a handful of sizable and comprehensive book-length studies. Masters pays tribute to influential works such as James Lee McDonough’s Stones River—Bloody Winter in Tennessee and Peter Cozzens’s No Better Place to Die, framing his own contribution as an effort to capture “the ground-level view experienced by the men in the ranks” (xii). Such a goal plays perfectly to Masters’s command of primary sources, and it is one upon which Hell by the Acre delivers abundantly.

Even with his emphasis on the fighting man’s perspective, Masters nonetheless fully situates the campaign in its political and military context. Stone Rivers occurred during an ebb in Union morale following repulses at Fredericksburg and Chickasaw Bayou in December 1862, all on the eve of the Emancipation Proclamation. Prior to the Federal advance on Murfreesboro, both Rosecrans and Bragg worked diligently, reorganizing and drilling their forces for the coming fight. Masters considers the composition and character of the rival armies, even surveying their respective armaments, a factor often overlooked in other campaign narratives. Masters points to a greater proportion of rifle-muskets among the Cumberlanders in contrast to more of Bragg’s veterans still carrying smoothbores, suggesting the Rebels would be “forced to get dangerously close to their opponents for effective firing” (23). He further describes the difficult approach by Union troops, hampered by winter rains and mud, as well as delaying tactics by Wheeler’s cavalry. On December 30, the two armies sparred with one another on the west side of Stones River as they jockeyed for position. Masters relates this skirmishing in such vivid detail that one might reasonably wonder why this doesn’t officially rank as the first day of the battle.

For December 31, Rosecrans and Bragg planned essentially identical attacks, each intending to hit his opponent’s right. Bragg managed to strike first, sending his left wing crashing into Alexander McCook’s corps. Bitter fighting ensued, giving rise to such grim battlefield landmarks as the Slaughter Pen and Hell’s Half Acre. One of Bragg’s staffers accurately noted the effect of the Confederate attacks of the Federals as “bending back their line as one half shuts a knife-blade” (387), leaving the Cumberlanders battered yet still holding the field in a denser, more compact position. Readers familiar with Masters’s blog and its sourcing of evocative soldiers’ accounts will not be disappointed with Hell by the Acre. “It is terrible to hear the singing of a bullet and follow its course as it flies on its way,” we learn from an Indiana officer, “and then hear that keen whistle of the little piece of lead suddenly terminate in a dull crash as the ball leaps through the brain of some friend beside you” (403). By the first day’s end, a rebel surgeon tells us, “The two armies lie opposite each other like two wild beasts exhausted with the rage of battle, eyeing each other ferociously and ready to spring upon each other’s throat” (507).

Though the first of the new year saw little direct combat, Masters does not give this phase short shrift. He details the command deliberations, the shuffling of units, and the collection of the wounded, observing, “Both armies spent January 1 mostly watching, waiting, and building breastworks” (527). January 2 saw Rosecrans shift additional troops east over Stones River to threaten the Rebel right. Bragg responded by ordering a reluctant John C. Breckinridge to attack. Confederates successfully drove Union forces back to the river, only to be pounded by massed artillery and driven in turn by a US counterattack. Emphasizing the soldiers’ perspective, Masters devotes less time to analyzing command decisions than other tomes, yet he still offers commentary at opportune points. Regarding January 2, Masters judges that, given the threat Rosecrans’s move presented, “Bragg’s proposed attack was not a tactical absurdity, but a tactical imperative” (544).

Hell by the Acre presents a compelling narrative of one of the Civil War’s deadliest but most understudied clashes, drawing from both familiar and untapped sources to paint a hard-hitting portrait of desperate fighting as viewed from the ranks. Author Daniel Masters brings passion and skill to bear on bettering our understanding of a critical western theater campaign—and the rival armies that battled so bitterly for Middle Tennessee and beyond.

Jonathan M. Steplyk is the author of Fighting Means Killing: Civil War Soldiers and the Nature of Combat.