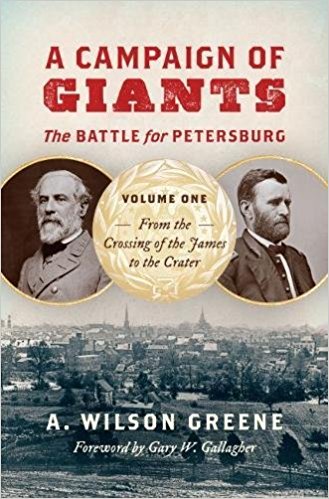

A Campaign of Giants: The Battle for Petersburg: Volume 1: From the Crossing of the James to the Crater by A. Wilson Greene. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1-4696-3857-7. $45.00.

The past few years have seen renewed interest in the operations around Petersburg, Virginia, from 1864-1865, with recent works by Gordon Rhea, Caroline Janney, and Hampton Newsome bringing much needed depth to an often-overlooked aspect of the Civil War. The Petersburg Campaign has always been part of the debate over the Civil War as a modern conflict, with the employment of extensive field fortifications being at the top of the list for those who argue that the campaign foreshadowed the Western Front of 1914-1918. This connection may explain the recent resurgence in Petersburg studies, with spillover from the centennial of the First World War contributing to a renewed curiosity in the largest example of trench warfare from the Civil War. Or, as in the case of A. Wilson Greene’s epic A Campaign of Giants, perhaps it was merely the recognition that, despite Petersburg’s length and complexity, it had never received the detailed examination directed towards other Civil War campaigns.

The past few years have seen renewed interest in the operations around Petersburg, Virginia, from 1864-1865, with recent works by Gordon Rhea, Caroline Janney, and Hampton Newsome bringing much needed depth to an often-overlooked aspect of the Civil War. The Petersburg Campaign has always been part of the debate over the Civil War as a modern conflict, with the employment of extensive field fortifications being at the top of the list for those who argue that the campaign foreshadowed the Western Front of 1914-1918. This connection may explain the recent resurgence in Petersburg studies, with spillover from the centennial of the First World War contributing to a renewed curiosity in the largest example of trench warfare from the Civil War. Or, as in the case of A. Wilson Greene’s epic A Campaign of Giants, perhaps it was merely the recognition that, despite Petersburg’s length and complexity, it had never received the detailed examination directed towards other Civil War campaigns.

The first part of a planned three volume analysis of the Petersburg campaign, A Campaign of Giants provides a welcome, comprehensive depiction of the longest continuous campaign of the war. Beginning with the Union movement across the James in mid-June 1864 and concluding somewhat abruptly with the immediate aftermath of the Crater at the end of July, Greene methodically walks the reader through the steps that led to the failure of Grant’s First and Second Offensives around Petersburg and the ongoing efforts to capture the city throughout the month of July.

His research displays fairness to both sides while incorporating materials from virtually every notable archival collection of relevance to the campaign. Greene weaves this together into a detailed narrative of the subject that explores the major components of military operations from a variety of viewpoints. For example, Greene’s portrayal of the Wilson-Kautz Raid of late June goes beyond a campaign narrative to bring in the larger impact that the failed cavalry strike had on the strategic visions of both sides—along with the response of the local populace, who found themselves amidst the chaos. Whether it is the ragtag collection of Confederate soldiers and civilians who held the defenses at Staunton River Bridge, the tired Union troopers who get roped into being captured a few days later, or the poor runaway slaves who found their hopes of freedom dashed by the operation’s outcome, their story is told convincingly and with a wealth of detail.

Greene attempts to present a full picture of all those concerned with the operations around Petersburg, stating early on that his work is intended to “strike a balance between providing enough tactical detail to satisfy demanding consumers of military history, while never losing sight of the campaign’s overall context,” and he is mostly successful in this regard (xiv). The citizens of Petersburg receive the attention they deserve, with the chapter devoted to their plight over the summer of 1864 being far more than a token check-in on those who found their home a battlefield. The soldiers of both armies also receive attention, but outside of their commentary on the First, Second and Third Offensives, the sections devoted to their everyday story seem less fleshed out. Hopefully the future contributions to this series will avoid the tendency to leap from offensive to offensive and provide a full exploration of the interregnum between major operations around Petersburg.

Inevitably, issues of command at all levels predominate in this study, with the “giants” of Lee and Grant often taking center stage in the discussion of major events throughout the campaign. The narrative focus tends to drift more towards the functioning of the Union command apparatus (perhaps understandably so, given the complicated structure that Grant inherited and perpetuated for at least the early weeks of the investment of Petersburg). Grant comes off poorly here; while Greene credits the Union commander with successfully deceiving Lee and the Confederate high command with his movement across the James, much of his analysis concerning the operations surrounding Petersburg finds fault with Grant’s command style. For example, Greene claims that Grant’s plan for the Second Offensive was one that “bordered on the geographically ludicrous” and displayed a “fanciful operational vision” (226, 234). Ultimately, it is Grant’s laissez-faire approach to the internal affairs of the forces surrounding Petersburg that gets repeatedly challenged in Greene’s analysis.

The difficulties created by the North’s command arrangements are vividly displayed in the concluding chapters on the Battle of the Crater. Greene demonstrates how the Union command floundered in the immediate aftermath of the mine explosion as brigade and division commanders vacillated over how best to proceed. A strong hand could have brought order to the chaos, but Ninth Corps commander Ambrose Burnside and Army of the Potomac commander George Meade remained absent from the immediate sector of engagement. Instead of seizing control of the situation, these commanders bickered with each other over real and imagined slights while General-in-Chief Grant remained nearby but reluctant to interfere with the inner workings of Meade’s army. Greene contrasts this with the Confederate command structure at the Crater, which, while still disappointing in some aspects at the brigade level, offered a clear lesson in the value of a strong army commander. As telegrams raced between Union commanders and some Northern generals sought comfort in the security of bombproofs behind the lines, Greene describes the steadying presence of Generals Lee and Beauregard on the field as “the two highest-ranking Confederate field commanders in the eastern theater picked their way south through ravines and broken ground” to take up position at the Gee House, only a few hundred yards from the Crater fighting (456-7).

To say that Greene’s research is exhaustive does not quite do it justice; as the former executive director of the Pamplin Historical Park, Greene brings a wealth of expertise to a subject that he has lived with for decades. While early on Greene dismisses use of the word “definitive” to describe his work, this first volume certainly establishes itself as essential reading for future scholars of the Petersburg Campaign.

Steven E. Sodergren is the author of The Army of the Potomac in the Overland & Petersburg Campaigns (2017).