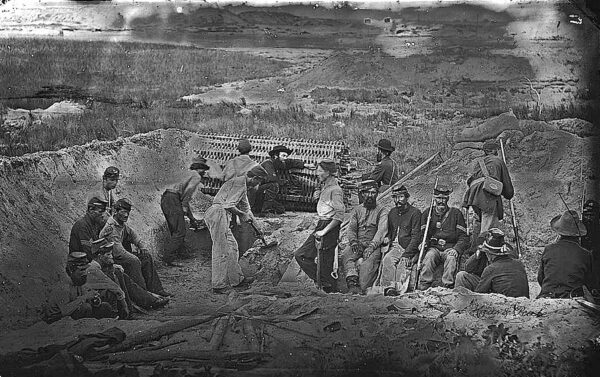

Union soldiers dig a trench on Morris Island, South Carolina, during the Civil War. Library of Congress

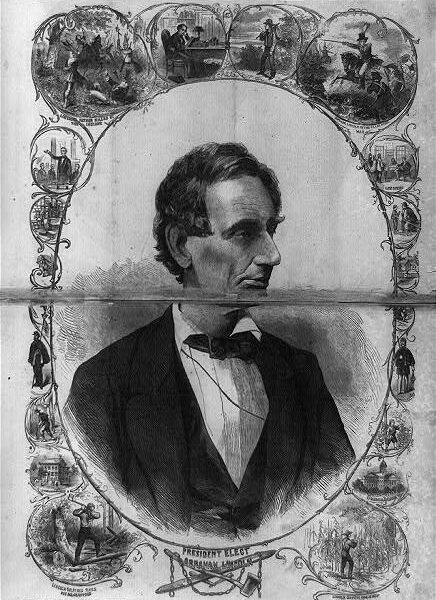

Library of Congress

In the Voices section of our Summer 2023 issue we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about life in the trenches. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that just missed the cut.

“I feel about as lame and stiff as a man can feel who is unused to such work.”

—Massachusetts soldier John H. Carter, on the work of digging trenches, in a letter home, September 5, 1861

“Still we lie here, in the trenches, doing nothing all day long; the burning rays of the sun, the dry, parched ground, ready to be blown away in clouds of dust by the slightest breath of air…. I guess I can stand two months of siege work; no more charging to be required of your humble sergeant-major….”

—Walter Carter, 22nd Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter home from the trenches of Petersburg, July 17, 1864

“The covered ways were six feet deep, twelve feet wide, the barricades of logs, were four feet high and four feet through. A wagon train could pass rapidly within one-quarter of a mile of the rebel earthworks. Our bombproofs consisted of an excavation about six feet square by six deep, covered with earth, under which were logs, and a little back cellar way was left on the side away from the enemy. Our shelter tents we pitched on top the bomb proof. Some lived in the upper story, but were always ready to drop down into the cellar whenever firing commenced. We had become so used and hardened to the danger that we sometimes became careless.”

—Massachusetts soldier Robert G. Carter, on the Union trenches at Petersburg, in a postwar account of the war

“We were shocked at the condition, the complexion, the expression of the men, and of the officers, too, even the field officers; indeed we could scarcely realize that the unwashed, uncombed, unfed and almost unclad creatures we saw were officers of rank and reputation in the army.”

—Confederate artillerist Robert Stiles, on arriving at the front lines at Petersburg during the siege of the city, in his memoir of the war

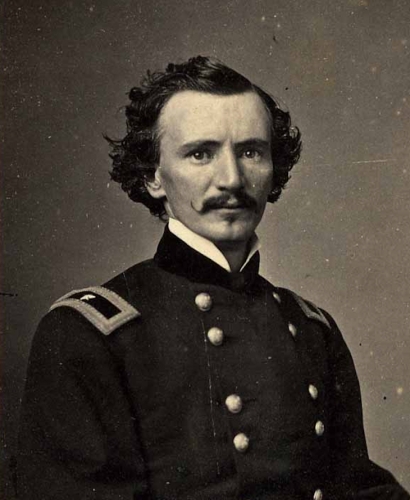

War Diary and Letters of Stephen Minot Weld, 1861-1865 (1912)

War Diary and Letters of Stephen Minot Weld, 1861-1865 (1912) Stephen Minot Weld

“The rebels are getting a splendid range on us with their mortar-shells. They are beginning to throw them into the trenches, which makes it slightly uncomfortable, as you can well imagine. They send a piece through my shanty occasionally. At night it is really good fun to watch them. You can see them gracefully ascending until they almost seem to stand still, and then down they come faster and faster, and finally explode. As a general rule, they do but little damage, for it is very difficult to get an accurate range with them. Just as I had written this, along came two mortar-shells, and burst within 40 feet of my shanty. Pleasant life we lead here, I can assure you. Yesterday we had our first rain for six weeks, and uncomfortable enough it made us, I can assure you. The trenches were half full of mud and water, as well as all the officers’ quarters. I slept last night in a perfect mud-hole, half drenched myself. To-day we have a regular dog-day. Hot and sultry, a day that makes one feel dirty and sticky all over.”

—Stephen Minot Weld, 56th Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter home during the Siege of Petersburg, July 20, 1864

“The scenes along the trenches at night were grand beyond description. For miles the bright little flashes of the musketry in two parallel lines were the brilliants surrounding the brighter gems of the cannon flashes. Darting across with the rapidity of a meteor from side to side, in opposite directions, flew the lighted shells in almost horizontal lines, while high above all in the heavens in graceful, arching flight flew in flocks of six or eight at a time, the mortar shells, looking as if they were chasing and passing and re-passing one another in their eagerness to perform their deadly mission. The flocks of mortar shells from opposite sides sometimes crossed each other’s paths and seemed for an instant tangled together, but then they would glide away and separate with the utmost grace. The flights of these missiles appeared astonishingly slow, indeed they did not seem to move faster than the flight of a bird; this was because there was nothing to compare their movement with except the ‘direct fire’ shells below, which of course moved with great velocity. Smoke spread a lurid tint over the scene, sometimes obstructing the view of the flashes of the guns, but lighting up beautifully from them. This scene had its effect intensely heightened by the mingled sounds wafted through the night air. The crackle of the musketry in all degrees of intensity, from the clear, sharp reports near at hand to the distant, scarcely audible shots, made almost a continuous sound, so rapidly did they reach the ear; while the booming of the cannon closely followed by the screaming and bursting of the shells came in irregular bursts, sometimes drowning all other sounds and then dropping off for a moment almost entirely. In between these bursts of sound and mingled with the rattle of the musketry the shouting of the men could be heard like the voices of demons in the infernal regions.”

—Confederate cavalry officer William W. Blackford, on life in the trenches during the Siege of Petersburg, in his memoirs

“As soon as a man showed himself during the daylight a bullet would come. Not more than one shot in fifty hit its mark, but it was nerve-wracking…. Every day someone in the Regiment was hit.”

—Rice Bull, 123rd New York Infantry, on coming under fire while in the Union fortifications outside Atlanta in 1864, in his diary

Wikipedia

WikipediaJoseph J. Bartlett

“We have never before used the Spade as we have this summer. In any two days of the campaign we have constructed more works than were thrown up by us two years ago during the whole time we were in front of Richmond.”

—Union general Joseph J. Bartlett, in a letter to a friend during the Petersburg Campaign, June 25, 1864

“The skill and rapidity with which our men construct these is wonderful and is something new in the art of war.”

—Union general William T. Sherman, on his army’s creation of fortified trench lines during the Atlanta Campaign, July 1864

“But few days had passed that every man of the division was not under fire, both of artillery and musketry. No one could say any hour that he would be living the next. Men were killed in their camps, at their meals, and several cases happened of men struck by musket-balls in their sleep, and passing at once from sleep into eternity. So many men were daily struck in the camp and trenches that men became utterly reckless, passing about where balls were striking as though it was their normal life, and making a joke of a narrow escape, or a noisy whistling ball.”

—Major General D.S. Staley, in his official report of the Atlanta Campaign, July 1864

“The mortars are thrown up a great height and fall down in the trenches like throwing a ball over a house—we have become very perfect in dodging them and unless they are thrown too thick I think I can always escape them at least at night.”

—Alabama soldier Crenshaw Hall, in a letter to his father during the siege of Petersburg, October 16, 1864

“The men in the trenches were cramped for room, and were unable to sleep except in the most uncomfortable positions. No one dared show a hand or head above the rifle-pits on either side. The hot sun beat down on them by day, and the dews or rain at night. The trenches became muddy and disgusting.”

—Edwin W. Payne, 34th Illinois Infantry, on the battle for Atlanta, in his postwar history of the regiment

“I don’t care about seigeing an other place as we did Vicksburg … for Id rather plow corn any day than to lay in a rifle pit in the hot sun there is but little fun in it.”

—Jasper Barritt, 76th Illinois Infantry, reflecting on the struggle for Vicksburg, in a letter to his brother, April 2, 1864

“I think there will be considerable shoveling for some time to come.”

—George Fowle, 39th Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter home as his regiment moved toward Petersburg, June 9, 1864

“Our entire Army very nearly is enclosed in one vast entrenchment.”

—Lieutenant Charles F. Stinson, 19th USCT, on observing the Union lines at Petersburg, September 11, 1864

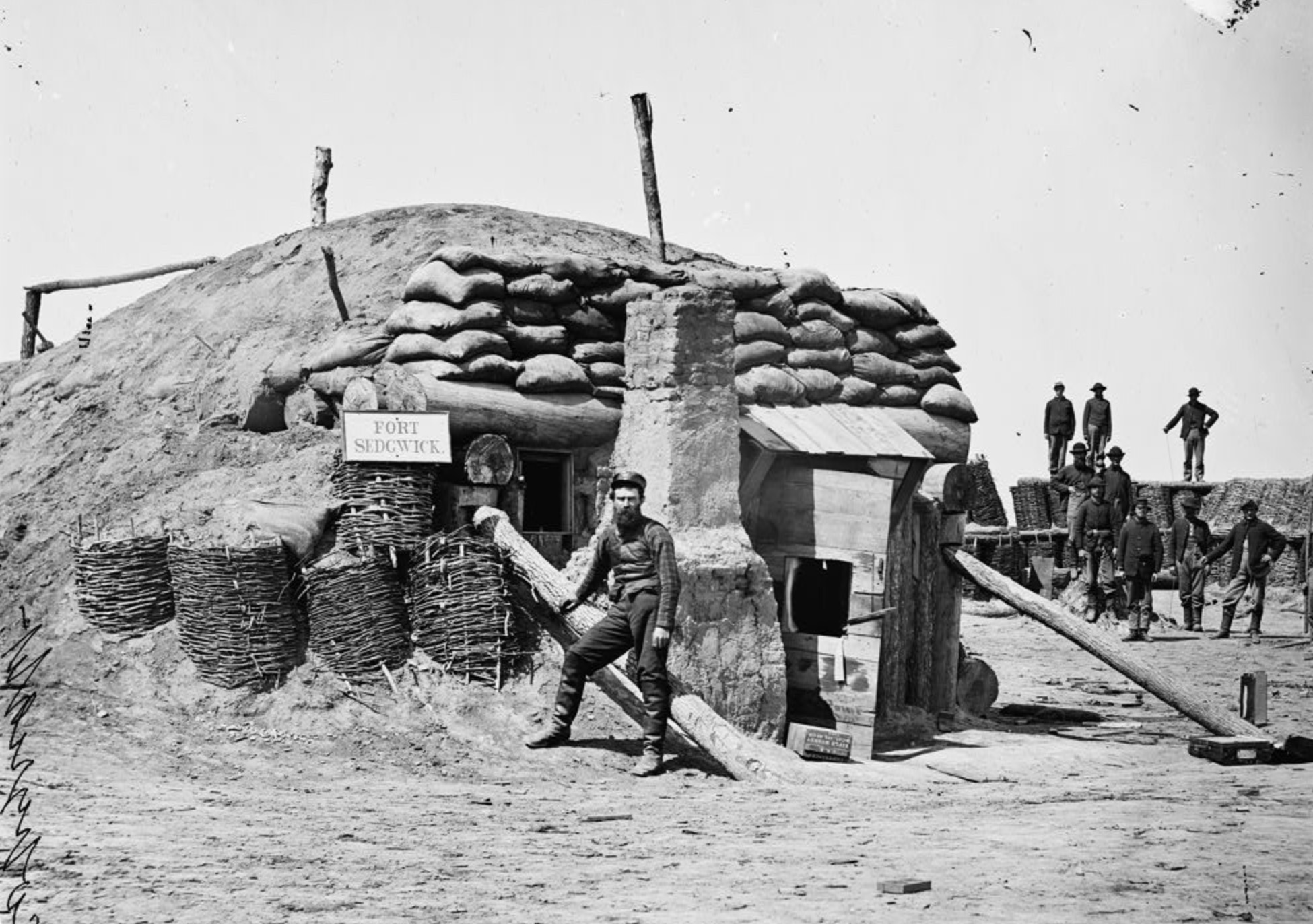

“My Battery is in Fort Hell, & it well deserves its name. I expend about 100 rounds of Ammunition every day, and the pickets and Sharpshooters pour in such a continuous stream of bullets that the said fort is anything but an agreeable place.”

—Union artillerist John Brinckle, on life in the defenses at Petersburg, in a letter to his brother, September 15, 1864

Library of Congress

Library of Congress A man stands in front of a bombproof shelter in Fort Sedgwick, also known as “Fort Hell,” one of many fortifications in the Union lines during the siege of Petersburg

“You would be astonished to see what formidable work men will erect during a night. If in a woods we cut down trees place three or four on top of each other after trimming of all branches then dig a ditch outside & through the Earth against the logs making the Earth work about six feet at bottom four on top and five feet high. [T]his will stop a cannon Ball, at the same time allow the men to fire on any attacking party.”

—Lieutenant Colonel George Hopper, 10th New York Infantry, in a letter to his siblings toward the opening of the Petersburg Campaign, July 2, 1864

“Work upon our breastworks which are about twelve feet thick. In front of them we cut down trees and make an abattis by ranging them in rows in front of the works, and sharpening all the stout limbs with a hatchet, so that it would be almost impossible to get through them. In front of this we felled large trees over the ground for two or three rods, so as to offer every possible impediment to the enemy if they attempt to advance.”

—Julius Ramsdell, 39th Massachusetts Infantry, on his regiment’s position in the lines at Petersburg, in his diary, June 30, 1864

“[W]hile we was eating a shell came over (a very common thing) and took a mans arm off. I got back to quarters safely.”

—Samuel Clear, 116th Pennsylvania Infantry, on life in the Petersburg trenches, in his diary, September 3, 1864

“They throw a great many shells at us but we don’t mind them much as we have bomb-proofs to get into. The men on guard sing out ‘shot,’ or ‘shell,’ and if it is shell we all dodge into our holes like so many rats.”

—Captain Thomas Bennett, 29th Connecticut Infantry, in a letter during the Siege of Petersburg, September 3, 1864

Sources

Four Brothers in Blue (1913); Four Years Under Marse Robert (1903); War Diary and Letters of Stephen Minot Weld, 1861–1865 (1912); War Years with Jeb Stuart (1945); Soldiering: The Civil War Diary of Rice C. Bull (1995); Bell I. Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank (1952); OR, Series 1, Vol. 36, pt. 1; OR, Series 1, Vol. 36, pt. 1; Bell I. Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb (1943); History of the Thirty-fourth regiment of Illinois Volunteer Infantry (1903); Paul A. Cimbala, ed., Soldiers North and South (2010); Steven E. Sodergren, The Army of the Potomac in the Overland & Petersburg Campaigns (2017).

Related topics: tactics