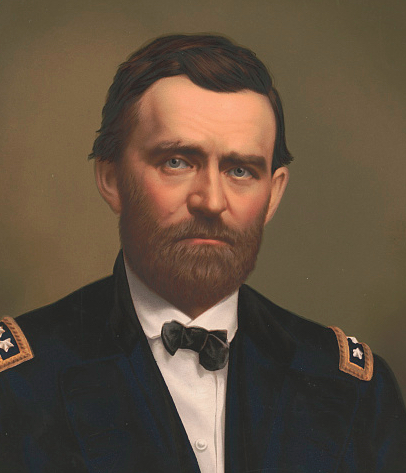

General Ulysses S. Grant

In 2014, we asked a panel of leading Civil War historians a series of questions about General Ulysses S. Grant—a way of assessing his record and legacy during the 150th anniversary of the Overland Campaign. And while the results were published in our summer 2014 issue (“Dossier: Ulysses S. Grant,” Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 16-17), space prevented us from providing all of our panelists’ answers in full detail. Below are some of their comments that were left on the cutting-room floor.

What do you most admire (a quality or skill, personal or professional) about Grant?

“I most admire his tenacity, which he demonstrated many times in many different circumstances.” —Michael Ballard

“Grant’s determination was not fueled by brute force, but by an amazing imagination hat allowed him to see possibilities when thought military matters looked hopelessly bleak.” —Peter Carmichael

“His unflappable steadiness in combat, almost a love of battle, and his aggressiveness, specifically his speed.” —Larry J. Daniel

“I most admire Grant’s ability to absorb disappointments, adjust plans accordingly, and press forward with remarkable tenacity and clear-eyed focus.” —Gary W. Gallagher

“Grant’s dogged and stubborn aggressiveness as a fighter and leader served the Union Army well in what became a ‘war of exhaustion.’” —Lesley Gordon

“His coup d’oeil—he could see and interpret terrain with uncanny skill, and almost feel the likelihood of enemy movement across it.” —Allen C. Guelzo

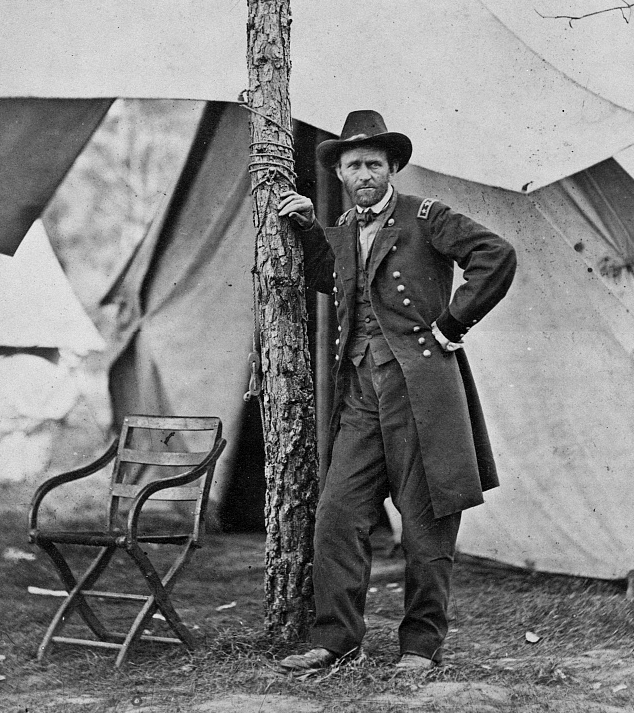

Grant at his headquarters in Cold Harbor, Virginia, June 1864

“Grant understood far better than McClellan (or anyone else for that matter) how to effectively work with his commander in chief. This quality, forming a working relationship with President Lincoln, even more than his fighting tenacity, was the key element for overall Union victory.” —M. Keith Harris

“His implacable resolve and willingness to stare down long odds, both on the battlefield and as president.” —Brian Matthew Jordan

“I am particularly impressed with the quality of Grant’s writing. He had the ability to make his thoughts, whether in combat or in writing to family and friends, succinct, clear, and insightful. His orders during the war were always obvious to his subordinates, and his desires and wishes were similarly clear in private communication. His memoirs are a model of good writing.” —John Marszalek

“His coolness in a crisis, his refusal to panic.” —James M. McPherson

“I have always admired Grant’s unpretentious ‘everyman’ nature, and more importantly so did the men under his command.” —Kenneth W. Noe

“I’m impressed by his awareness of his own qualities and those of others around him.” —Gerald Prokopowicz

“His pragmatic flexibility and adaptability.” —Ethan Rafuse

“Grant seldom complained about the hand Washington dealt him. With the tools (cards) he had he built success.” —Stephen W. Sears

“U. S. Grant’s ability to grasp—and more importantly, act upon—the truism that politics and war are one and the same separated him from many of his general-officer contemporaries; this helped him forge a mutually supporting relationship with his civilian authority during the years 1861-65 and aided him immeasurably as he executed the nation’s policy to subdue the military power of the Confederacy.” —Christopher S. Stowe

“Tenacity. Grant was an elemental man who simply plowed ahead, whether in war or politics, until he achieved his ends.” —Daniel Sutherland

“Grant’s fixity of purpose kept him from being easily derailed as he pursued strategic objectives while his unflappability in a crisis had a calming effect on his subordinates and ensured they would continue to do his will.” —Gregory Urwin

“Grant’s innate optimism and sense of fairness are admirable. But I especially admire his ability to adapt his strategy and politics to new evidence and changed circumstances. This is especially evident in his wartime embrace of emancipation and black enlistment as the “heaviest blow yet given the Confederacy.” —Elizabeth Varon

“A quality his contemporaries valued, and noted time and time again: his resoluteness in the face of discouragement.” —Joan Waugh

What was Grant’s biggest (personal or professional) flaw?

“Sometimes he allowed personal feelings, and his West Point background, get in the way of judging certain Union generals.” —Michael Ballard

“At crucial times he underestimated his enemies, both militarily and politically.” —Peter Carmichael

“Postwar political naïveté.” —Larry J. Daniel

“He sometimes allowed aggressiveness or overconfidence to get him into trouble, as when Lee turned both his flanks on May 6 in the Wilderness and when he placed his army in a very vulnerable position at the North Anna.” —Gary Gallagher

“Can we go post war? If so I would say he was too trusting (or maybe naïve) when it came to other people and his personal finances.” —M. Keith Harris

Grant and his war horse, Cincinnati

“He was an incredibly poor judge of character when it came to junior officers and, most especially, his political underlings.” —Brian Matthew Jordan

“Like Lincoln, he over-estimated the good will and under-estimated the ill will of others; unlike Lincoln, he lacked the political acumen to compensate for that shortcoming while in the White House.” —Chandra M. Manning

“Grant’s flaw militarily was what Sherman praised him for: his unconcern for what the enemy might be doing out of his sight. In his political and personal life, he unwisely had unquestioning confidence in and support of those he considered his friends.” —John Marszalek

“Too little attention to potential enemy initiatives that might take him by surprise.” —James M. McPherson

“Grant had his favorites, and it was never good professionally to be on the outside of that inner circle.” —Kenneth W. Noe

“As a general, he learned to rely on talented subordinates to do their jobs well, but that characteristic didn’t serve him well as president.” —Gerald Prokopowicz

“His personal decency and confidence led him to underestimate folks with ill-intentions—this was evident in his military, political, and business career and translated into unnecessary casualties on the battlefield, problems in his presidency, and business failure.” —Ethan Rafuse

“Early in the war, his obeisance to Halleck; he soon got over that.” —Stephen W. Sears

“It should not come as too much of a surprise that his most significant vice was a willingness to trust those people who were unworthy of that trust; in turn, he also tended to be a good hater who never quite forgot a slight.” —Brooks D. Simpson

“Grant was often too trusting of the motives of his personal and political favorites; this led him at times to make personnel choices that embarrassed him and, more importantly, adversely affected the national interest.” —Christopher S. Stowe

“Stubbornness. This is the dark side of his tenacity, and seen mostly in his dealings with friends and subordinates (whether for good or ill) during his presidency.” —Daniel Sutherland

“The flipside of Grant’s optimism was a certain naivete, especially about the capacity of his own magnanimity to change Confederate hearts and minds in the immediate postwar period.” —Elizabeth Varon

“Grant’s inability to delegate wisely to subordinates damaged his presidency, and thus Reconstruction, particularly in his second term.” —Joan Waugh

“He had difficulty judging the character of men with whom he had not worked closely.” —Stephen Woodworth

Participants: Michael Ballard; Peter Carmichael; Larry J. Daniel; Gary W. Gallagher; Joseph Glatthaar; Lesley Gordon; Allen C. Guelzo; M. Keith Harris; Brian Matthew Jordan; Chandra M. Manning; John Marszalek; James M. McPherson; Kenneth W. Noe; Gerald Prokopowicz; Ethan Rafuse; Stephen W. Sears; Brooks D. Simpson; Christopher S. Stowe; Daniel Sutherland; Gregory Urwin; Elizabeth Varon; Joan Waugh; and Steven Woodworth.

Related topics: Ulysses S. Grant