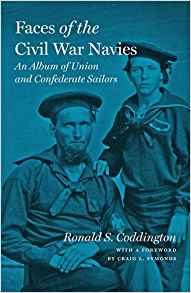

Faces of the Civil War Navies: An Album of Union and Confederate Sailors by Ronald S. Coddington. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1421421360. $32.95.

There is a certain level of satisfaction that arises from being able to match a physical face, rather than a mere description, to a name and story. Out of the seventy-two carte de viste and five tintype portraits reproduced within Faces of the Civil War Navies: An Album of Union and Confederate Sailors, no two images appear the same: whether from a change in posture, a change of backdrop, or from the addition of friends, family members, and, in one rare case, a dog. Similarly, of the biographies researched and conveyed by author Ronald S. Coddington, no two sailors present an identical version of the war. While naval ship design, tactics, officers, and weaponry improvements have been intensely researched and discussed in the Civil War narrative, too often forgotten are the personal stories of the sailors aboard those ships who, as Coddington explains, “laid down their lives amidst grim scenes of carnage on blood-soaked decks and from contagions of yellow fever and other dreaded diseases in cramped quarters far away from land and loved ones.”

There is a certain level of satisfaction that arises from being able to match a physical face, rather than a mere description, to a name and story. Out of the seventy-two carte de viste and five tintype portraits reproduced within Faces of the Civil War Navies: An Album of Union and Confederate Sailors, no two images appear the same: whether from a change in posture, a change of backdrop, or from the addition of friends, family members, and, in one rare case, a dog. Similarly, of the biographies researched and conveyed by author Ronald S. Coddington, no two sailors present an identical version of the war. While naval ship design, tactics, officers, and weaponry improvements have been intensely researched and discussed in the Civil War narrative, too often forgotten are the personal stories of the sailors aboard those ships who, as Coddington explains, “laid down their lives amidst grim scenes of carnage on blood-soaked decks and from contagions of yellow fever and other dreaded diseases in cramped quarters far away from land and loved ones.”

Working from the success of three previous volumes—Faces of the Civil War, Faces of the Confederacy, and African American Faces of the Civil War—Coddington brings to life these men aboard the battleships, be they closer to home, anchored along a river bank, or farther away in the seas, prowling for enemy ships. Despite allotting only a few pages to each sailor, Coddington still succeeds in providing long overdue recognition to both these sailors’ mental and physical battles.

Researching the individual histories of seventy-seven sailors (starting with just a photograph and, if lucky, possibly a name, rank, or ship) is difficult—especially because, as Coddington acknowledges, the official records for the navy are “surprisingly scant,” or in the case of the Confederacy “practically nonexistent.” Yet rather than admit defeat, Coddington, in addition to trips to the National Archives, local archives, and libraries, utilized modern technology to find naval pension files and service information. From these sources, Coddington produces what he calls “informed biographies,” arranged roughly chronologically and focused largely around one key date or naval battle in which that sailor was involved. The majority of these pictures, hidden away in private collections, have never before been published.

Despite the difficulty in obtaining these images, the selection of photographs assembled by Coddington still manages to convey a solid presentation of the scope of men affected by the war, be they like Union Landsman George F. Ormsbee, who managed to attended basic training despite being a minor (having no facial hair to hide his youthful appearance), or older men such as Confederate Captain Thomas Jefferson Page, whose picture shows him grimacing underneath a bushy, white beard. Compared to the 2.1 million soldiers in the Union army, the Union navy comprised of only 84,415 sailors. The Confederate navy contained only 5,213 sailors. Therefore, it should not surprise readers to discover that there are a disproportionate number of Union sailors represented, with only sixteen photos displaying Confederates. Officers are likewise overrepresented. Of the fifty-one Union sailors, only two are African-American.

The war displayed no favoritism; nor does Coddington, who highlights that the war deeply affected every participant. Many sailors found little to no recognition, but instead battled illnesses (such as yellow fever, seasickness, or complications from amputations) and isolation. Nor did Appomattox signal the end of war for all sailors, be they Confederate First Lieutenant John Grimball, whose ship, the Shenandoah, “continued to operate for months after the surrender,” or Union Surgeon Edward Sylvester Matthews, whose injuries sustained in battle annexed him until the end of his life.

Despite its many strengths, the book does have a few minor shortcomings. For example, while it can be overlooked, it is difficult for anyone poorly versed in the vernacular of naval command to properly understand the multiplicity of titles and their corresponding roles. Also confusing for a non-specialist audience is the array of ship designs. A glossary might have efficiently explained the difference between a schooner, frigate, gunboat, and an ironclad. Some readers may also find the lack of a table of contents page a peculiar formatting choice. Regardless, Coddington’s collection of portraits and “snapshot” biographies, as described by historian Craig L. Symonds in his forward, “remind us that the history of war is not merely a chronicle of campaigns won and lost; it is the collective personal odysseys of thousands of individual life stories.” We should hope that Coddington might bring additional faces to life in future works.

Briana Weaver is an M.A. candidate at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas.