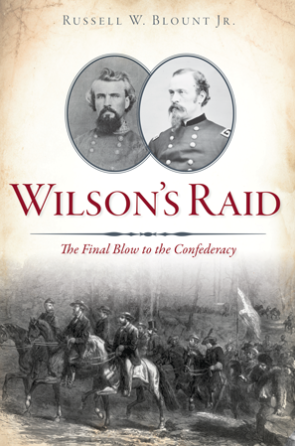

Wilson’s Raid: The Final Blow to the Confederacy by Russell W. Blount, Jr. The History Press, 2018. Paper, ISBN: 9781467139038. $21.99

By the final months of the Civil War, Union cavalry had reached a level of horsemanship that put them on par with their gray-clad counterparts. This enabled them to conduct independent offensive operations far exceeding their traditional functions of scouting, intelligence gathering, and screening. Russell W. Blount, an independent historian, has chosen to chronicle one such operation that he aptly calls “the greatest cavalry adventure of the Civil War.” It has come to be remembered in history as “Wilson’s Raid.”

By the final months of the Civil War, Union cavalry had reached a level of horsemanship that put them on par with their gray-clad counterparts. This enabled them to conduct independent offensive operations far exceeding their traditional functions of scouting, intelligence gathering, and screening. Russell W. Blount, an independent historian, has chosen to chronicle one such operation that he aptly calls “the greatest cavalry adventure of the Civil War.” It has come to be remembered in history as “Wilson’s Raid.”

At sunrise on March 22, 1865, the bugler at Gravelly Springs, Alabama, sounded “Boots and Saddles”; 13,480 blue coated troopers swung into the saddle to begin the largest, and most audacious, cavalry raid ever mounted on the North American continent. They were supported by three veteran artillery batteries of four guns each; 1,500 dismounted men; support personnel including surgeons, cooks, clerical staff, and regimental bandsmen; 250 supply wagons; and a train of pontoon boats hauled by fifty-six teams of mules. This impressive show of strength was one cog in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s grand plan to finish off the South once and for all. They would move in conjunction with Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s campaign through the Carolinas and Brig. Gen. Edward R.S. Canby’s drive to capture the city of Mobile, Alabama, from the south.

Before it was over, the blue troopers, divided into three columns, all superbly mounted and heavily armed, would cleave their way 653 miles deep into the cradle of the Confederacy, destroying the South’s last remaining industrial production centers and bringing the ferocity of war to civilians previously insulated from its destruction. Led by Brigadier General James Harrison Wilson, the brash, young “boy general” known to be a favorite of commanding general Ulysses S. Grant, the raiders would smash their way through northern Alabama and parts of Georgia, confront and defeat the remnants of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s once vaunted gray horsemen, and capture the fleeing Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, outside of Irwinville, Georgia, on May 10, 1865.

Blount’s dynamic prose moves with the celerity of Wilson’s mounted columns. He has chosen a narrative strategy not often employed by historians. By writing in the present tense, Blount gives the reader a sense of being in the midst of the action. He makes excellent use of anecdotal evidence gleaned from his extensive research into letters, diaries, memoirs, and contemporary newspaper accounts. Also helpful are the thumbnail biographies Blount provides for the diverse cast of characters involved in this unprecedented operation.

Entering North Alabama, the Union columns find a landscape “sterile and destitute in every direction.” Five days into the invasion, the weather takes an ugly turn and Wilson learns that Bedford Forrest’s widely scattered units are on the move. The objective for both sides is Selma, “The Queen City of the Black Belt.” Selma is both a manufacturing center and “the center of a transportation network that binds together practically all the remains of the Confederacy east of the Mississippi River.” The city is protected by a significant fortifications network and about 4,000 defenders composed of exhausted Confederate cavalrymen and a collection of poorly armed, untrained civilians. Blount notes that “the fortified line is so long that to cover it the men are standing at intervals of six to ten feet, a distance too far apart to effectively hold off a Federal force as strong as Wilson’s.”

Blount’s account of the Selma attack on April 2 is a model set piece of battle narration. He deftly includes the observations of civilians like Mattie Harrell who, “stands alone with her invalid mother and two younger children…Now as she stares up the road leading to the first line of the city’s defenses she sees ‘the dark cloud of blue coats which shortly formed on the horizon, growing more ominous.” No match for the bluecoats, Forrest orders the defenders to escape as best they can, leaving the city and its citizens to the vengeful invaders. For the next week, Selma endures a nightmarish occupation. On Palm Sunday, April 9, Wilson’s columns trot out of the ruined city, unaware that 700 miles to the northeast, Ulysses S. Grant has extinguished the brightest light of Confederate arms at Appomattox.

Next in Wilson’s sights is Montgomery, the birthplace of the Confederacy. Yet on April 11, Brigadier General Dan Abrams is informed by General Richard Taylor “‘to attempt no defense of Montgomery’ but rather move his infantry to Columbus, Georgia…for the defense of that city.” The next morning, blue troopers under General Edward McCook trot up Market Street to accept the surrender of the city from Mayor Walter Coleman. The raiders then continued on to Tuskegee and Opelika before striking at Columbus, Georgia. On the evening of April 17, “as Wilson and his raiders ride out of Columbus, the city lays smoldering in rubble and ashes.” On April 20, Wilson and his men finally halt in Macon, Georgia, their destructive drive at an end.

The History Press has augmented Blount’s excellent narrative with numerous photographs and simple, yet informative maps. Taken together, Wilson’s Raid can serve as a model for presenting an analytic campaign study without becoming bogged down in academic jargon. Historians like Russell Blount are a welcome addition to the ranks of Civil War chroniclers.

Gordon Berg’s articles and reviews have appeared in numerous Civil War publications. He writes from Gaithersburg, Maryland.