The Bugle (1899)

The Bugle (1899)The Battle of the Crater

In the early morning hours of July 30, 1864, Union forces besieging the city of Petersburg, Virginia, attempted to gain a decisive advantage. For weeks, miners had dug an underground shaft toward the Confederate position. After reaching it, they packed the shaft with explosives; when fired, the mine exploded a massive crater in the Rebel line. Instead of exploiting the resulting confusion to their advantage, Union forces that attacked after the explosion were ultimately repulsed after suffering significant casualties, their advance quickly disorganized by the crater itself and strong Confederate counterattacks. Afterward, Ulysses S. Grant called the failed and bloody assault “the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war.”

One of the Union soldiers involved in the fight at the Crater wrote a detailed account of his experiences, which the U.S. Sanitary Commission published as part of a book—Soldiers’ Letters, from Camp, Battlefield and Prison—of Union soldier correspondence released in 1865. Identified only as a “Staff-officer,” his account follows in full.

Before Petersburg, Aug. [1864]

I am tired and sleepy with a hard day’s work: it is so hot, can’t go to sleep, and the flies have bothered me nearly to death—made me nervous and twitchy. My temper is getting horribly irascible under these afflictions, joined to chronic mental irritation, occasioned by the prevalence of knaves and fools. I probably shall not write long, but go and sit under the general’s tent-fly, and gnash my teeth.

I suppose you would like to hear my account of the affair of the 30th, and my part therein; but I have not dared to write about it, fearing I should say things I ought not to. Matters are mixed enough without my getting into a scrape.

But here is a sketch. But, by the way, don’t you admire my reticence in saying nothing of the Mine, though my mind has been full of it for so long? Tell Heinrich I have a pipe for him, made out of clay dug out of the face of the Mine, clear under the enemy’s works.

I was up the Mine the day before it was charged. Conceive, my child, entering the earth by a hole about four feet square, and continuing up that hole, bent nearly double, for nearly six hundred feet; lighting your uncertain steps through deep and sticky mud, by a candle held in one hand.

Arrived there you sit down, panting and perspiring, and listen to our friends the enemy pegging around over your head, hammering at gun platforms, rolling barrels, &c, which noises come to you very distinctly, though dull and muffled. It is a very odd sensation. Perhaps the rest can best be described by mingling it with my personal experience.

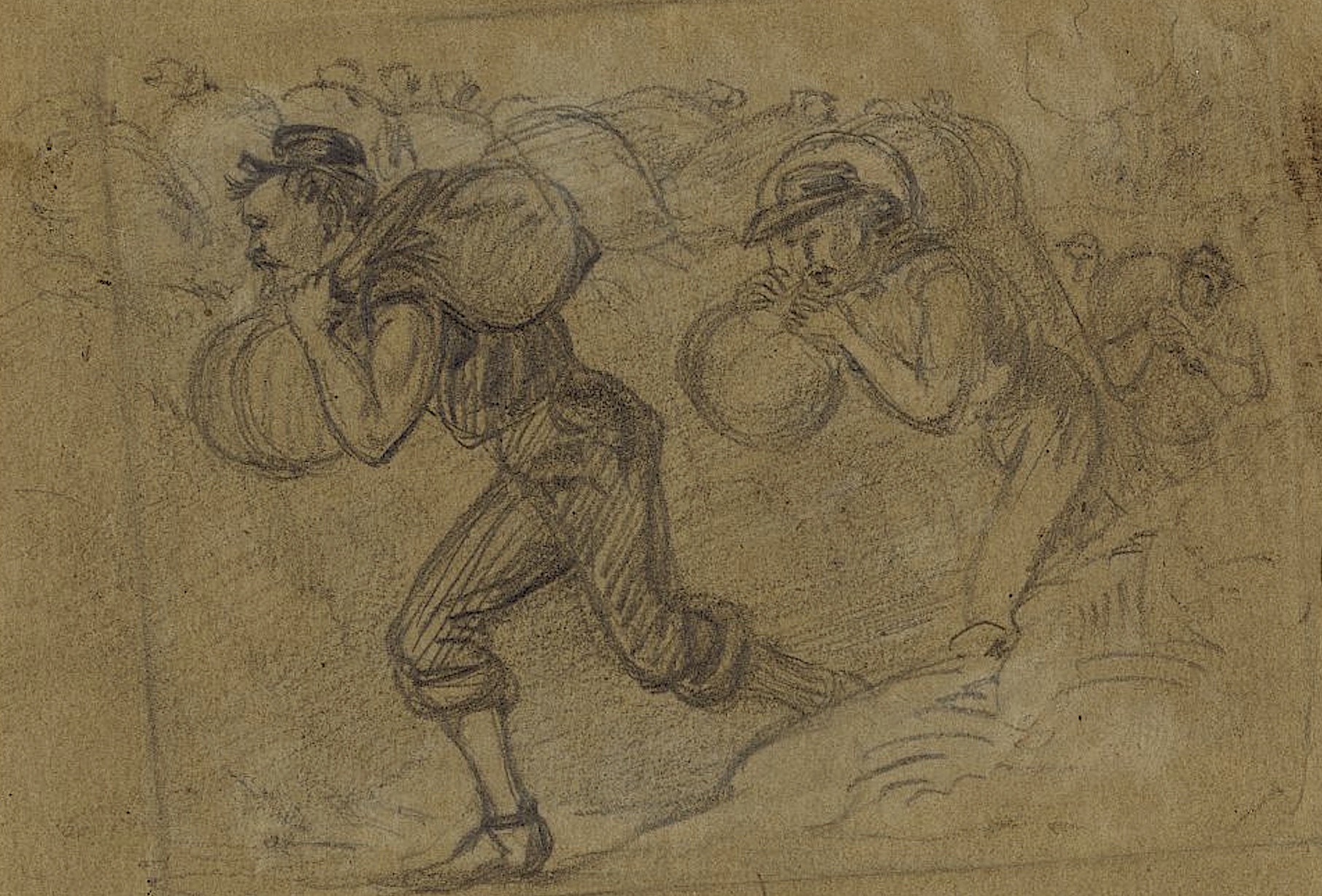

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAlfred Waud’s sketch of miners carrying powder in preparation for exploding the mine at Petersburg.

Three of the staff were detailed to go with the First, Second, and Third Divisions. I was to go with the Second Division, under General Potter. I awoke at 2 o’clock, a.m., received instructions from General —, and rode over about 3 o’clock. Went to the front with General —, where we were told that the fuse at the Mine had been fired, and the explosion would take place at 3:41. It was still quite dark, and we stood on a hill-side, opposite the enemy’s line—fifteen thousand men lying on their arms just below us, ready for a rush at the enemy’s position.

The appointed time came—no explosion. Ten minutes passed—twenty—we began to look blank at each other. I got on my horse and rushed over to see the general, who was further to the left; wondered with him what the row was, and rushed back. Officer came up, and reported failure in the fuse; had been relit, and would be off at 4:42.

By this time it was quite light, and not much chance of taking the fellows in their beds. Punctually, at 4:42, we felt a trembling of the earth, a dull heavy explosion; and I jumped out upon the parapet in time to see a huge fountain of rebel fort and smoke, rushing 150 feet into the air. One hundred and twenty guns opened with a terrific crash. Our columns charged—the enemy’s line was gained, and the ball opened. But now the bad effect of our six weeks’ crouching behind breastworks was apparent. The enemy opened a hot fire, and there was some difficulty in getting the men beyond the shelter of the enemy’s line, towards the crest we were to take. Started after fifteen minutes’ delay; but the head of the column was shivered by the hot fire, and came back. Other troops were put in, but the line of works they had to cross was so crowded with men, that confusion resulted. But Potter’s Division went in well, and nearly gained the crest, but were driven back by the concentrated artillery fire. The Third Division went in on the left, and captured another fort, part of their line, and some prisoners.

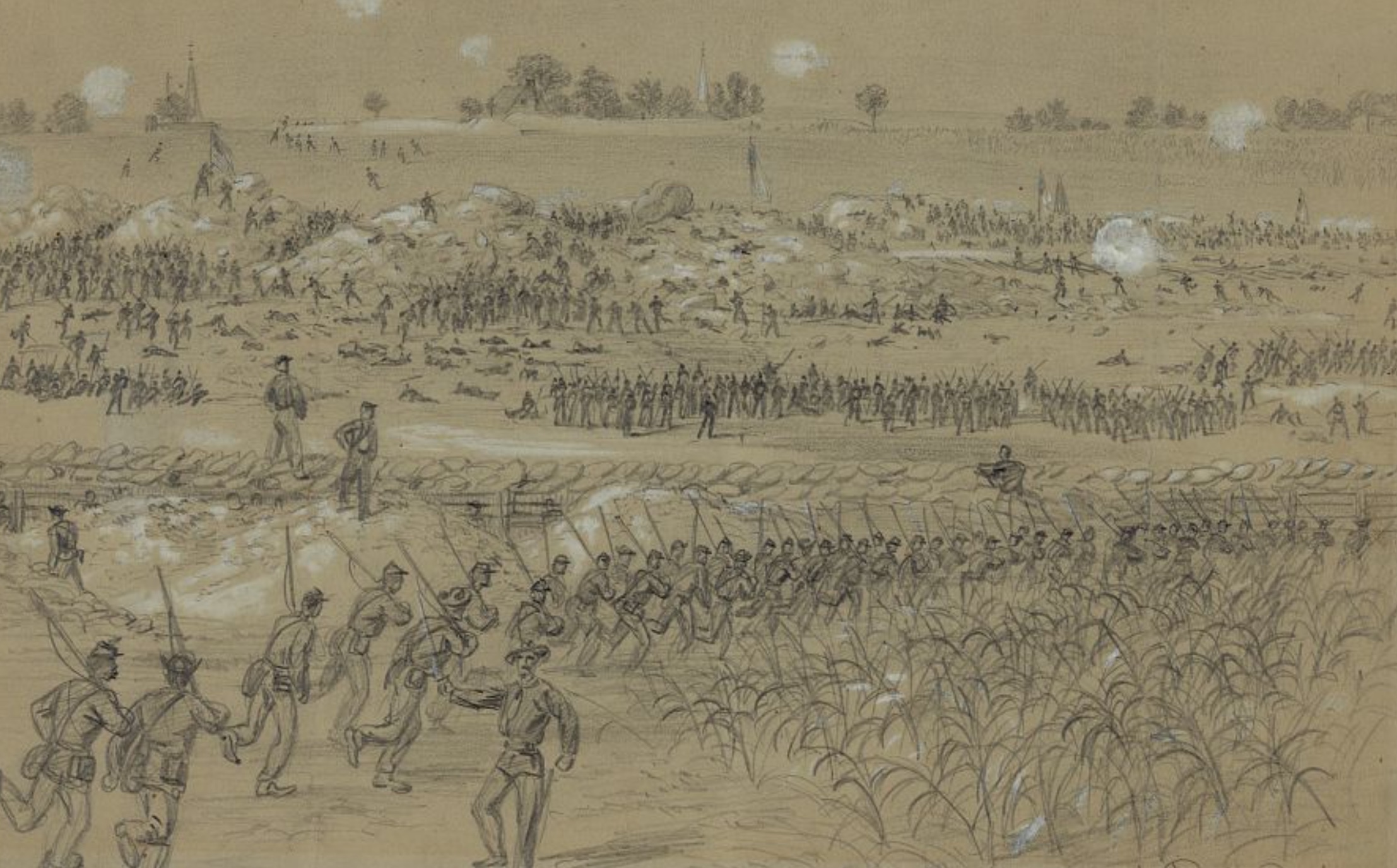

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUnion soldiers advance toward the crater shortly after the mine explosion in a sketch by Alfred Waud.

I began to get anxious, and went down myself. The process of getting from our front line to the crater of the Mine was not pleasant, the rebs keeping up a cross-fire on the space between. I climbed over our works, and ran like a trooper to the other line, some one hundred and fifty yards, and stopped behind a large chunk of earth on the outer slope of the crater to rest, surrounded by a mass of dead rebels, and some of our own wounded, one of whom kindly suggested to me that I was on the wrong side of the chunk; and a bullet nearly taking the top of my head off, proved he was right. So I proceeded inside the crater, where I found some of the brigade commanders. I brought orders to advance; and just as I got there, written orders from General — came to his division; so Colonel — and I went down the rebel pits to the right, dead and wounded rebels so thick you couldn’t avoid stepping on them. Two or three hundred yards down the line we came to the end of our troops, and the beginning of the rebels, who were firing at each other round an angle in the works, and twenty feet apart, quite sociable and pleasant.

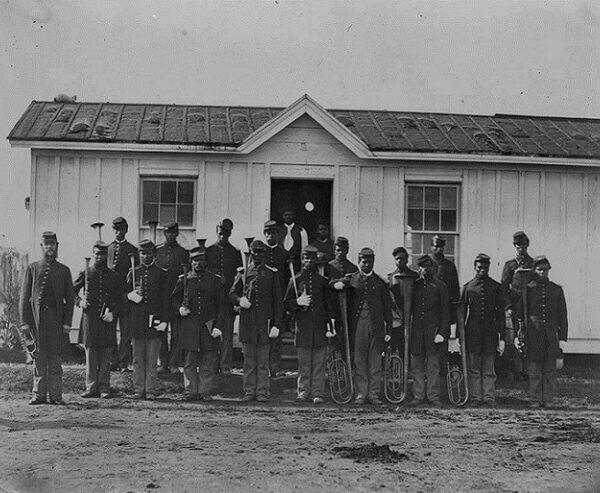

I helped —— form his brigade, and we jumped upon the bomb-proof and tried a charge, but ran into so hot a fire that the men broke. Were just reforming them, also the brigade behind ours, when the colored troops came bulging down the pits, knocking our line all to pieces. The colonel who was leading them wanted instructions where to go, and I gave them, showing how we could take a crook in the enemy’s line, and probably bag most of the rebs there. So we got the fellows out of the pits, and made a rush for this part of the line, and took it, with a battle-flag and a lot of prisoners. It was exceedingly hot for a few minutes; but I have wonderful fortune, and came out unhurt, though with my clothing spattered with the blood of fellows hit around me. The darkies, certainly, went in well. I then went back, and met the other brigade of negroes coming in tip-top style. I stood in the centre, cheering, waving sword, &c, as did the other officers there, and urging the darkies to go in well. The ridge of the crater where they had to cross was pretty well swept with bullets, and not a pleasant place to go over; and there they betrayed rather a tendency to crawl. So I stood near there, and distributed cheers, blessings, expletives, and whacks of my sabre with great liberality.

At last the most of them were through, and were being formed towards the enemy for a charge, and I sat down to rest, nearer dead than I care to be again. The sun was frightfully hot, no water to be had. I was without breakfast, and it is a mercy I didn’t have another sunstroke. The crater was filled with the debris of regiments broken up going through, the sides black with men; the enemy were getting the range of it with shell and schrapnel, rendering it unpleasant. Spang! a shell would strike right in a swarm of men: two or three would turn over dead, and others limp away wounded. Slap! a lot of case-shot would strike the other side, while overhead the canister was almost like a horizontal hailstorm—musket-bullets were, of course, also prevalent.

I forgot to say that during this last charge through the crater I was powerfully reminded of the picture of the taking of the Malakoff, of which you have a print. There was the same rugged blown-up appearance, fragments of gabions, sand-bags, gun-carriages, dead men; great chunks of earth, with perhaps a man sticking out from beneath; and ghastly dead all around—color-bearers, waving their flags—officers their swords and hats, &c. Of course, there was not the hand to hand skirmishing there is in the picture I speak of, still the general features on a somewhat smaller scale were like it.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsAdolphe Yvon’s painting of the Battle of Malakoff, fought in 1855.

I then went down the line again to see the commanders of the negro brigade that was to charge, gave him final instructions, and then started back to communicate with the general. By this time the enemy had got perfect range of the space between the crater and our advanced line, and it was more unpleasant going back than it was coming out: the whole crest of the crater was swept with a storm of bullets. I don’t think I ever disliked a trip quite so much; so I rested for a few moments behind the edge, talking with the colonel of one of our black regiments, then started over the top and ran like a good one for our lines, about one hundred and fifty yards, but it seemed about a mile and a quarter. Took a flying leap over our breastwork—safe and surprised—worked my way up to the general and reported.

Just then the darkies charged—were repulsed, and came back confusedly; adding to the crowded crater and pits of the enemy a mass of panic-stricken negroes.

It was a great mistake putting in the colored division at that time, but the general had imperative orders from General Meade to do so.

Directly after this repulse of the darkies, the rebs came down on our position, but were very handsomely repulsed. Then came an order for us to withdraw from the enemy’s line, and close the fight. And so we quietly backed out with much loss from a half-fought field, with three corps behind us who had not been engaged; only one brigade of any other corps than this was engaged the 9th Corps.

Staff-officer.