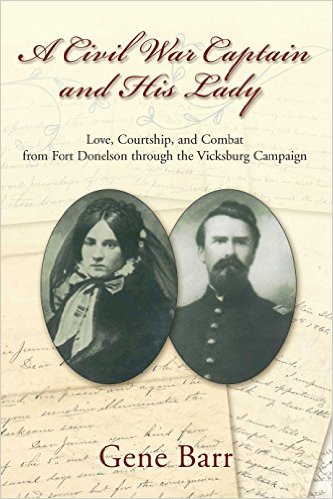

A Civil War Captain and His Lady: Love, Courtship, and Combat From Fort Donelson through the Vicksburg Campaign by Gene Barr. Savas Beatie, 2016. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1611212907. $32.95.

With A Civil War Captain and His Lady, Gene Barr presents a collection of letters between Josiah Moore, a Union officer in the 17th Illinois, and his fiancé, Jennie Lindsay. His narrative identifies elements of courtship and the importance of spiritual faith as central themes of the wartime romance. At the same time, he seeks to place the correspondence in the context of the major military and political moments of the Civil War’s western theater.

With A Civil War Captain and His Lady, Gene Barr presents a collection of letters between Josiah Moore, a Union officer in the 17th Illinois, and his fiancé, Jennie Lindsay. His narrative identifies elements of courtship and the importance of spiritual faith as central themes of the wartime romance. At the same time, he seeks to place the correspondence in the context of the major military and political moments of the Civil War’s western theater.

Barr’s work is primarily a narrative of the Union war effort in the west, following Josiah’s regiment from the Union capture of Fort Donelson in 1862 through their occupation of Vicksburg in 1863. The narrative is straightforward and based almost entirely on secondary sources; the footnotes reveal extensive reading of the major works on the subject. Barr’s unique contribution is his exploration of the courtship of Josiah and Jennie. Following the firing on Fort Sumter, Josiah left Monmouth College and enlisted in a local company, where the men elected him captain. The company joined the 17th Illinois and reported to Peoria for training. It was here that Moore met Jennie, the daughter of prominent attorney and local politician John Lindsay.

Over the course of his three-year service in the Western Theater, Josiah courted Jennie, and the two became engaged during one of his furloughs to Peoria. In this span, the two exchanged more than seventy-five letters. This unique collection includes letters from both Josiah and Jennie, or at least until 1864, when Jennie’s letters are missing. A Civil War Captain includes the couple’s complete transcribed and annotated wartime correspondence, offering readers an interesting glimpse into the wartime courtship between a soldier at war and a woman on the home front. A young couple in love, the letters are full of expressions of regret at the distance that separates them. Jennie shows great concern for Josiah’s physical and spiritual well-being and frequently implores him to seek furloughs. Though Josiah remains committed to the war effort, like so many other young men in his situation, he grows impatient with army life and musters out when his enlistment ends on June 4, 1864. Together, they maintain a deep spirituality, each placing their faith in God to see them to the end of the war, and their separation.

Indeed, the correspondence only rarely goes beyond these sentiments. Josiah acknowledges participation in engagements such as Fort Donelson and Shiloh, but for details he defers to the battle reports he is sure Jennie has already read. Josiah is reluctant to share details about the war with his fiancé, with the exception of the Vicksburg campaign, where he describes the hard fighting of Grant’s failed assaults on the town and the dangers of sharp shooters during the siege. The two are silent on the war’s larger issues, such as emancipation. While Josiah expresses his support for the Union’s decision to enlist African American troops, his views on Union contraband policy, emancipation, and the Union cause remain less clear. Citing an essay Josiah wrote while at Monmouth praising John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, Barr suspects that Josiah was sympathetic to the Republicans and emancipation (198). He attributes Josiah’s silence to the Peace Democrat majority at home, a group that included Jennie’s father, who left the Republican Party and became an outspoken Copperhead. Likewise, beyond the daily activities of family members, Jennie does not reveal much about life or public opinion on the home front. While this leaves Jennie’s views unclear, Barr attributes her silence to a desire not to disrespect her father while avoiding upsetting Josiah.

The couple’s reticence about the war turns out to be a considerable obstacle for Barr, who wants to tell a story of love and combat. To offer a complete narrative of the Western Theater, he includes sections on military action, Union policy on runaway slaves, emancipation, and the increasingly popularity of Peace Democrats in Illinois. Barr intersperses letters between Josiah and Jennie in this timeline, even though the couple’s missives are silent on these issues. To compensate, Barr relies on letters from other soldiers and civilians. By using manuscript collections from other men of the 17th Illinois, Barr does create a detailed history of Josiah’s regiment. But in trying to tell two stories at once—placing the budding romance of Josiah and Jennie in the context of the violence and politics of war—the collection will likely frustrate readers, who will finish a passage on the various opinions of Union soldiers on slavery, for instance, and then read a series of letters between Josiah and Jennie which instead discuss day-to-day life and how much they miss one another.

Perhaps Barr’s exploration of these letters could have been more effective if placed in a different context. In comparison with other soldiers’ letters, was it unusual for Josiah and Jennie to be so silent on major issues during the war? James McPherson found that it was not uncommon for soldiers to avoid describing battlefield horrors in their letters home (For Cause and Comrades, 12-13). He also notes that in his extensive examination of soldiers’ letters, their usefulness varied greatly (McPherson, 183). So while the silence of Josiah and Jennie on military and political issues is frustrating, perhaps it was not uncommon. Instead of thinking about these letters from a military standpoint, Barr could have focused more heavily on themes of courtship and gender. There may have been more we could have learned from a greater engagement with the letter collection as a means of wartime courtship and spiritual guidance, as they were by far the most significant themes of the letters.

In this collection, Barr intended to place the courtship and correspondence between these two young people into its Civil War context. In this, he offers a clear narrative of the Civil War and the lives of Jennie and Josiah. But in so doing, he leaves open an opportunity for greater engagement with historians such as Karen Lystra who have studied the romantic nature and emotional depth of nineteenth century correspondence. There is still more we can learn from the actual content of the letters, the emotions expressed in them, and the nature of the young couple’s wartime courtship.

Michael Johnson is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at George Washington University. From 2014 to 2015, he served as an Editorial Assistant for The Journal of the Civil War Era.