National Museum of American History

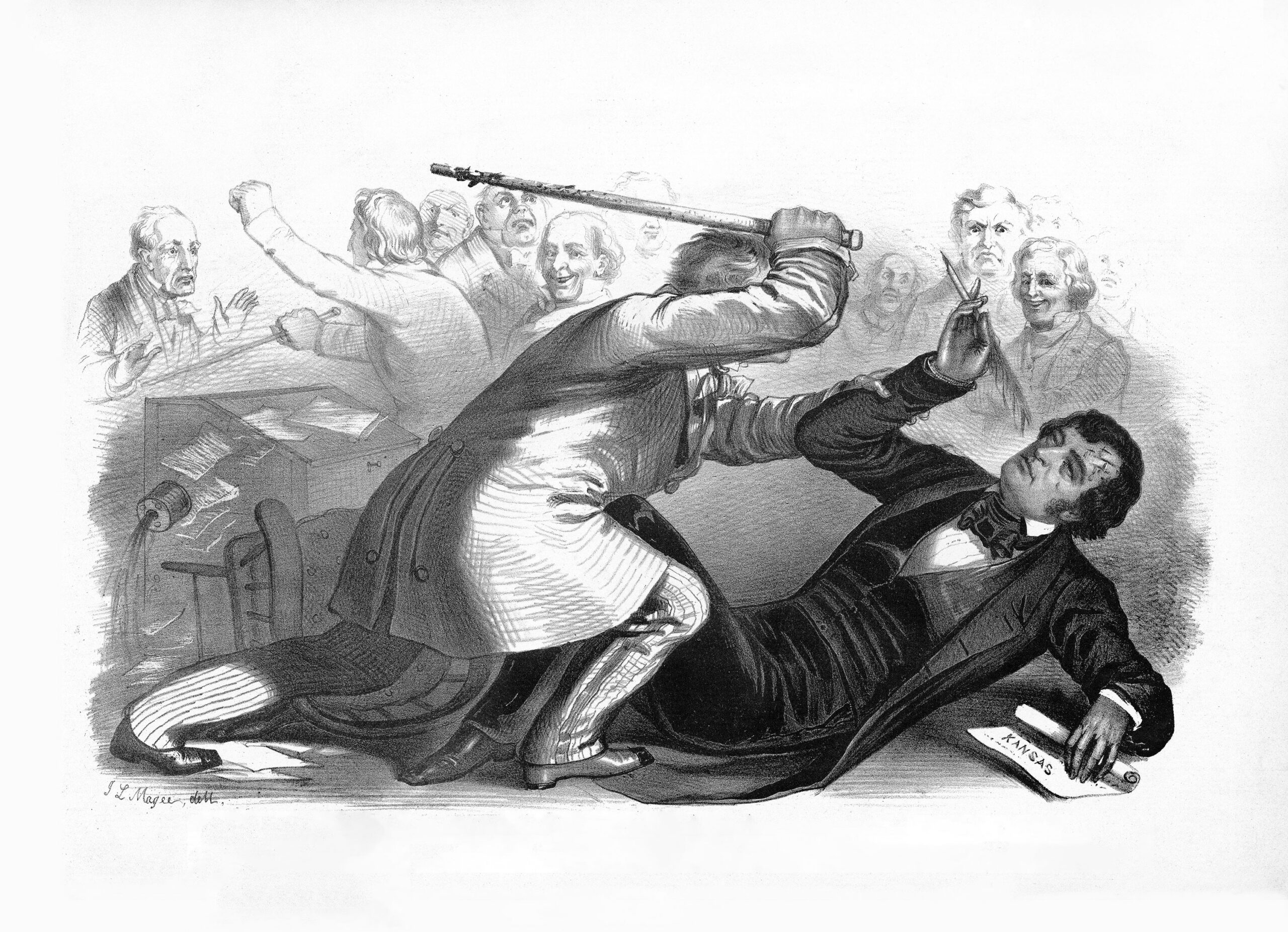

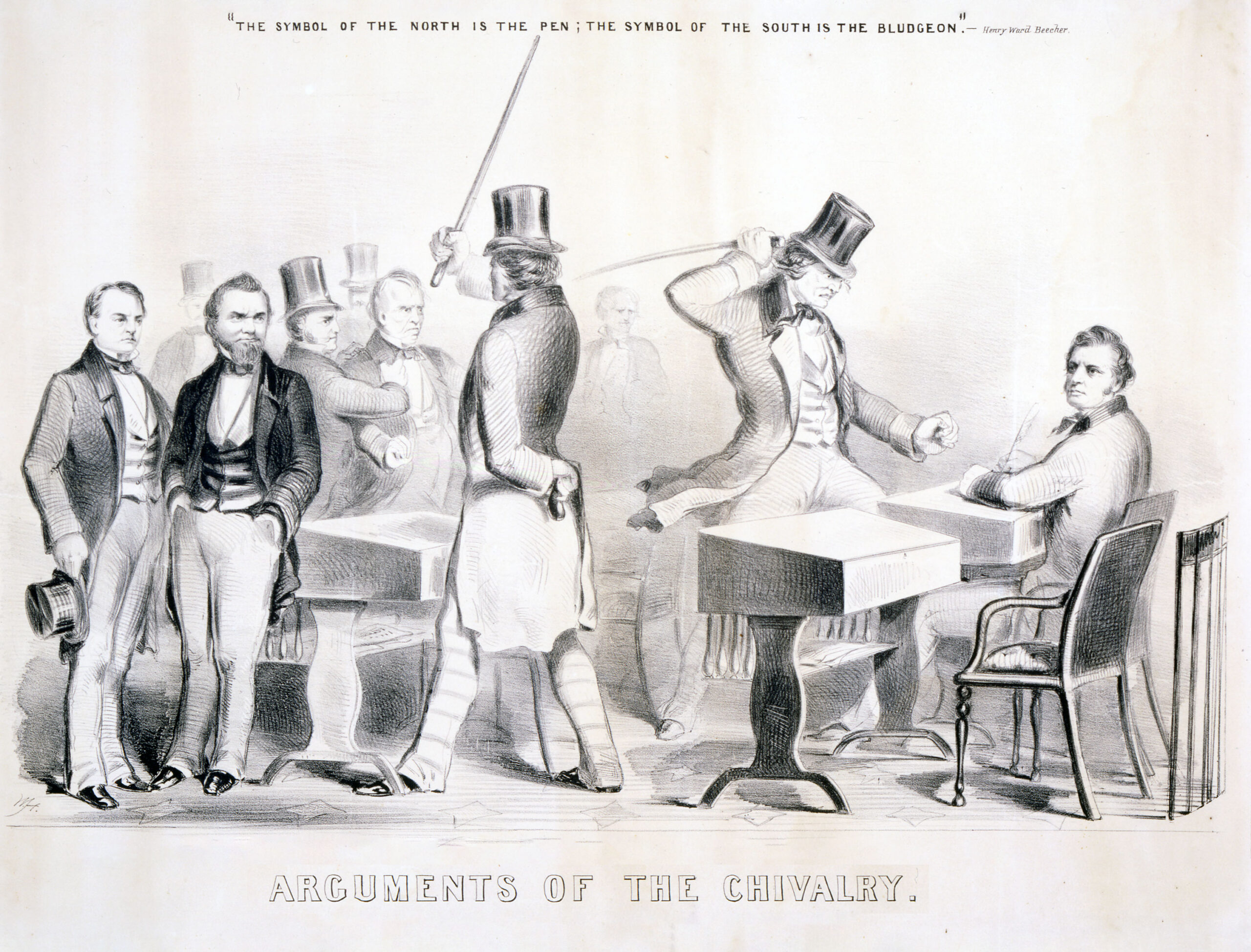

National Museum of American HistoryThis illustration by John L. Magee depicts the assault on U.S. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts by Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina on the Senate floor on May 22, 1856, days after Sumner had delivered his “Crime Against Kansas” speech, in which he condemned the tactics of pro-slavery supporters in the territory.

It was the sound that most people noticed first. “My attention was suddenly attracted by a noise,” recalled one bystander. Another remembered hearing “a noise, thumps, pounding, and rustling disturbance.” A third “heard a scuffle, and some disturbance.” Several witnesses reported the sound of a “blow” being struck, while others described what they heard as “a crash,” “a sudden and unusual noise,” “a sharp crack.”1 No one expected to hear a cane striking a man’s skull—not in the Senate chamber of the U.S. Capitol.

It was approximately 1:30 p.m. on May 22, 1856, and the Senate had adjourned, yet the chamber was not empty. Several senators lingered, writing at their desks. There were visitors and men stood conversing in small clusters. The murmur of voices drifted around the room. Everything sounded precisely as usual, for that time, for that place, until the first, sharp crack sliced through the air, demanding attention, signaling something extraordinary.

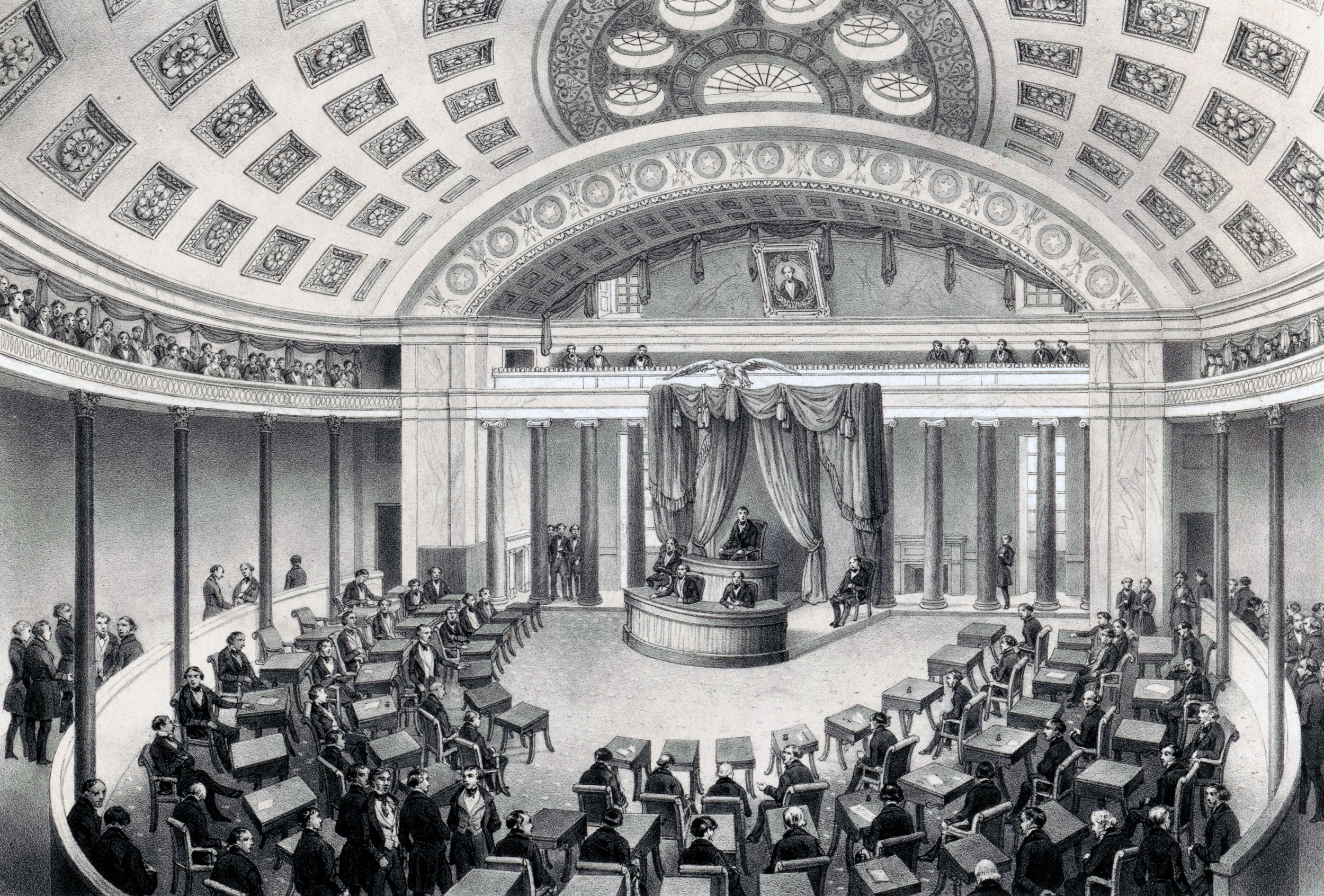

The Senate chamber reflected the majesty of the U.S. Congress. A semicircle 75 feet long and 50 feet wide, it was topped by an ornately carved half-dome ceiling and lit from above by skylights. The floor was carpeted in blood red, there were masses of gold-accented crimson drapes and rows of lustrous mahogany desks and chairs, with marble columns on one side and cast-iron pillars on the other. A golden carving of a mighty eagle perched on a shield and Rembrandt Peale’s portrait of George Washington looked over the resplendent space, proudly conveying the decorum and authority of the U.S. Senate.

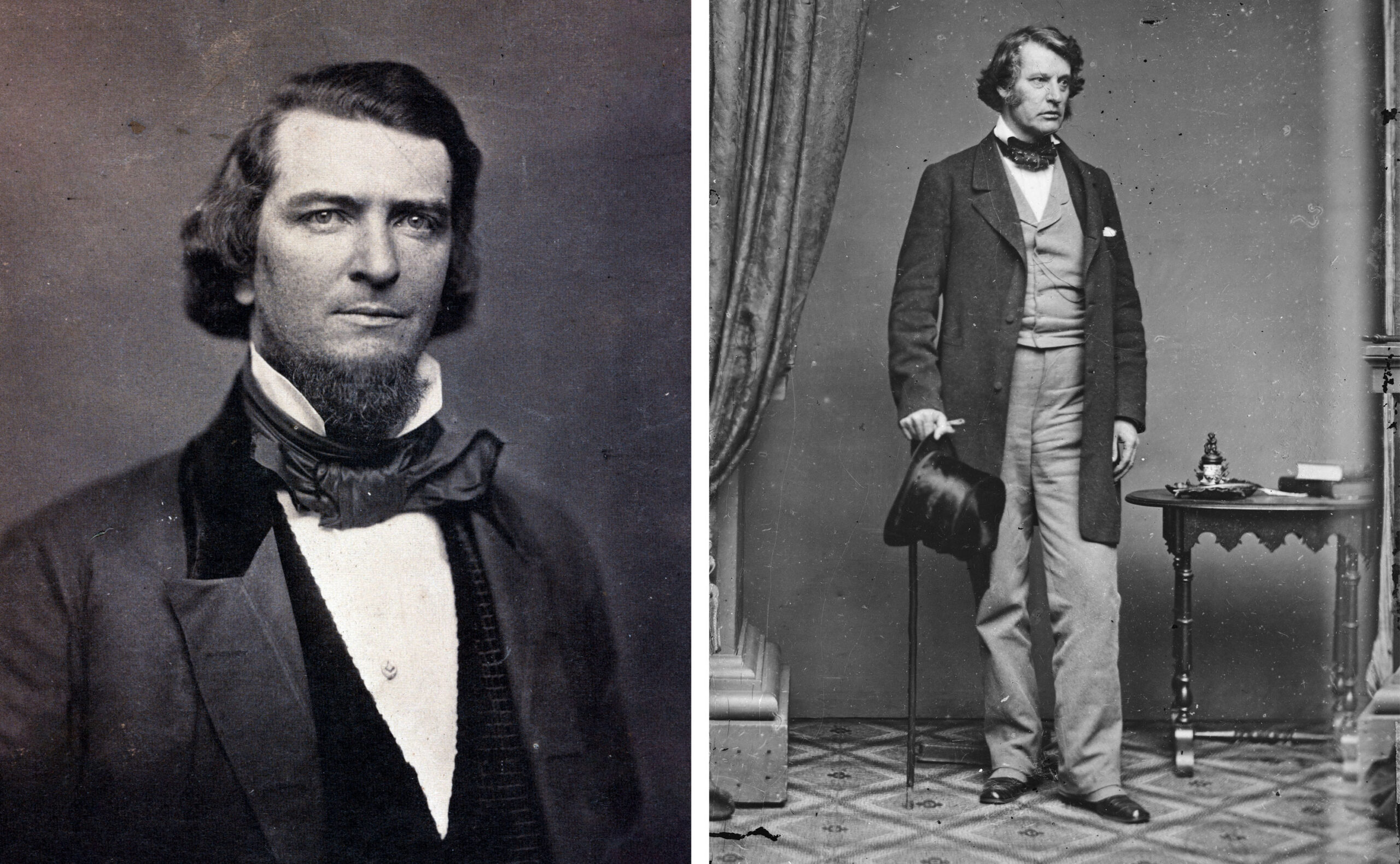

Library of Congress

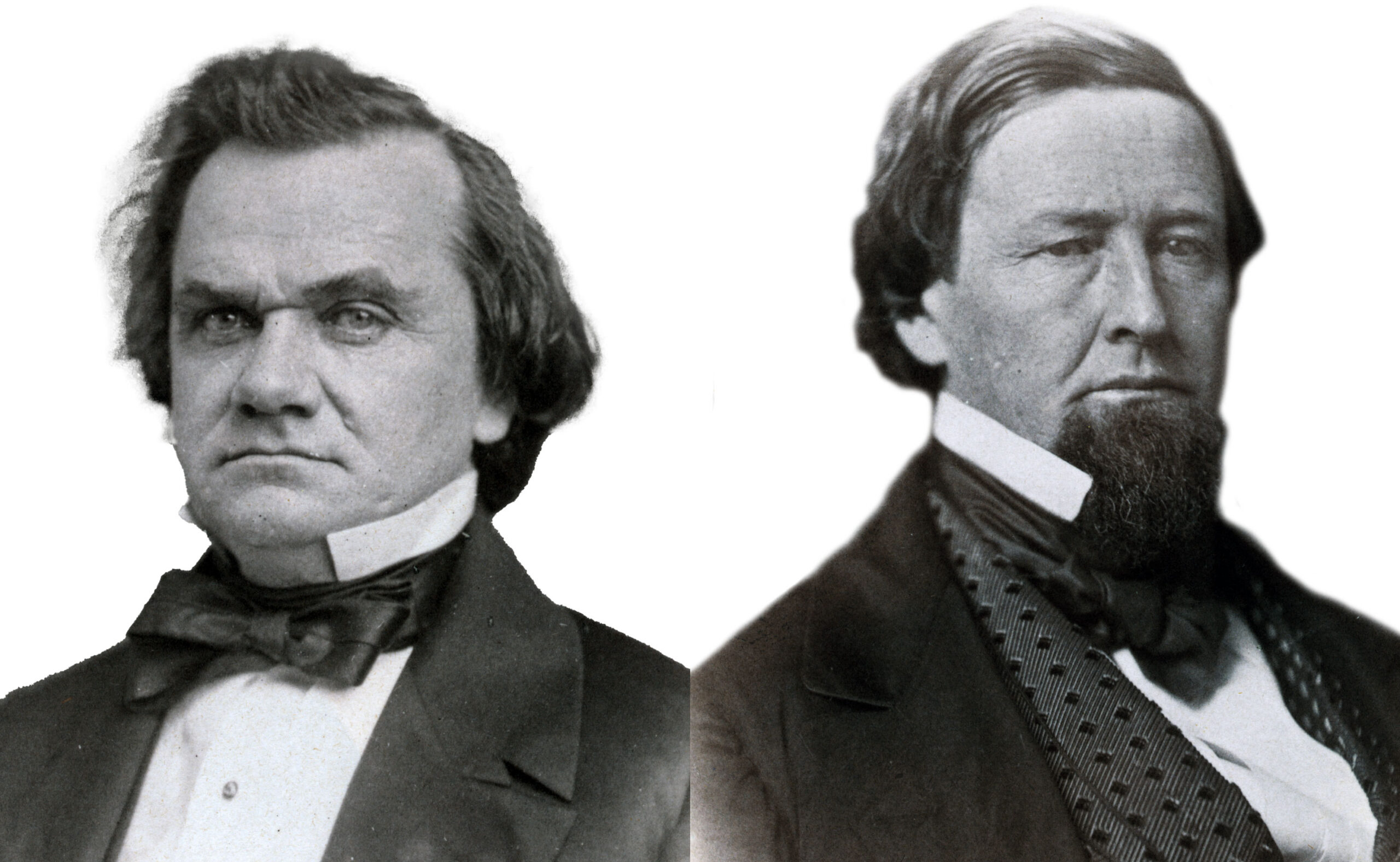

Library of CongressStephen Douglas (left) and Henry Alonzo Edmundson

At the same time, it was a busy workplace. Whether the Senate was in or out of session, the place was in constant motion: senators moving back and forth from their desks to the lobby area, separated from the rest of the room by a glass screen; visitors thronging the galleries overhead or seeking out senators on the floor below. Dozens of the desks were crammed together. And then there was the carpet. While visiting Washington in 1842, Charles Dickens attended the Senate regularly, describing it as a “dignified and decorous body,” but one whose carpets were greatly stained “by the universal disregard of the spittoon.” “I will merely observe,” he wrote, “that I strongly recommend all strangers not to look at the floor; and if they happen to drop anything … not to pick it up with an ungloved hand on any account.”2

So this was a room both grand and grubby; a bustling legislative marketplace and a place of awesome solemnity; a place where the work of governing was done, whether noble or otherwise; a place of venomous invective as well as soaring debate. But on that May afternoon, none of the business of the Senate made the loud wooden crack any less jarring.

The violence that took place that day stemmed, as violence often does, from words, words spoken that week, in that room, by Senator Charles Sumner. A consummate Bostonian, Sumner, 45, was intellectually rigorous, well traveled, deeply knowledgeable in the classics and the law, invested in schemes to better the human condition that ranged from penal reform to the peace movement to abolitionism. Elected from Massachusetts in 1851 to succeed Daniel Webster, he was smarter and better read than almost everyone around him—and he knew it. At 6 feet, 2 inches tall, he was an imposing presence; he’d had to have his desk in the chamber raised some inches to accommodate his long legs. A photograph taken around this time shows a somewhat haughty countenance, his features firm but beginning to melt into the softness of middle age, his head topped with an impressive mane of thick, untamed hair and his bushy sideburns beginning to gray. He had the sunken eyes of a man who worked too much, read too much—and the resolute eyes of a man certain it was all for noble purposes.

Sumner was known for delivering long, erudite speeches, sprinkled with classical and literary references, and sometimes including clever personal insults. That week, he had outdone himself. For three hours on the afternoon of Monday, May 19, and continuing the following day, Sumner delivered “The Crime Against Kansas,” a major intervention in the debate over the looming admission of the new state. Sumner was appalled by what he saw as a far-reaching conspiracy to ensure that Kansas welcomed slavery and slaveholders, a campaign orchestrated by the “Slave Power”—a term northerners were increasingly using to describe slaveholders’ schemes to bolster the “peculiar institution.” Sumner decried “the rape of a virgin territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of slavery.” In violently imposing slavery upon Kansas, slaveholders and their allies were attacking the foundation of their government, and even civilization itself.

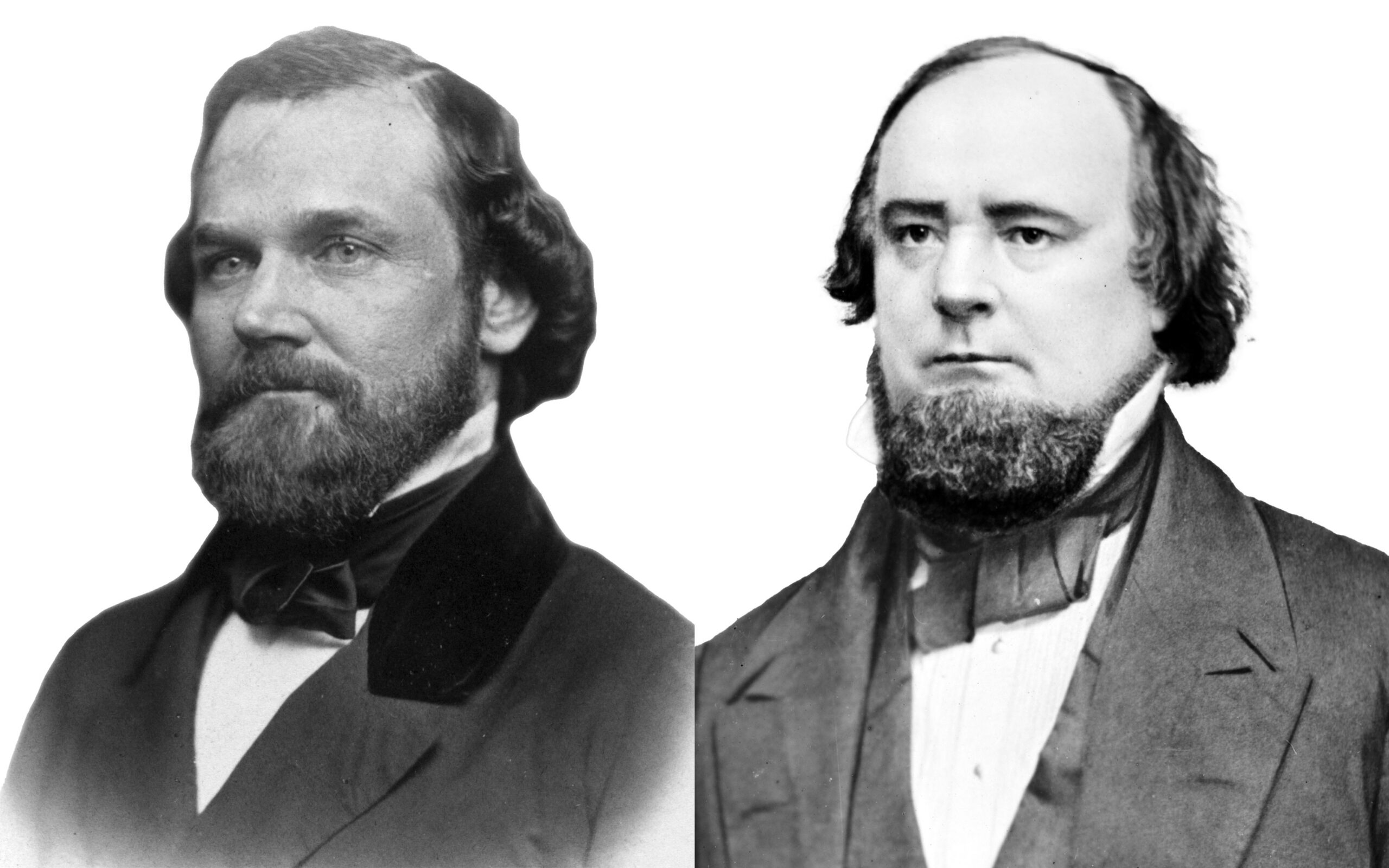

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAt the time of Brooks’ assault on Sumner, the Senate chamber (depicted above in an antebellum lithograph) was a room both grand and grubby, a resplendent space with carpets stained “by the universal disregard of the spittoon,” in the words of one contemporary observer.

For most of the speech, Sumner castigated the Slave Power in general terms. But he targeted specifically two fellow senators: Stephen Douglas of Illinois and Andrew Butler of South Carolina. He mockingly compared the two men to the principal characters in Cervantes’ 17th-century classic, Don Quixote; Butler was the aging, delusional, wannabe-knight Don Quixote while Douglas played his bumbling sidekick, Sancho Panza. Sumner’s harshest invective was reserved for Butler, who “has read many books of chivalry and believes himself a chivalrous knight, with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean the harlot, Slavery.” Mocking a South Carolinian’s sense of honor and chivalry; likening the acquisition of land to rape; depicting slavery as a repulsive prostitute—Sumner certainly knew which insults to hurl.3

These were indisputably fighting words. Perhaps it was lucky for Sumner that Butler was absent from the Senate that day. On the other hand, perhaps an immediate response from Butler would have been preferable to what did take place.

The immediate reaction from several senators—including northern Democrats—was hardly friendly. The day it concluded, Lewis Cass of Michigan called the speech “the most un-American and unpatriotic that ever grated on the ears of the members of this high body.” Douglas wondered about Sumner’s goal, “Is it his object to provoke some of us to kick him as we would a dog in the street, that he may get sympathy upon the just chastisement.” More quietly, he muttered, “That damn fool will get himself killed by some other damn fool.”4

Then there was Preston Brooks. Within days he would become a household name, but as he listened to Sumner’s tirade in the Senate chamber, he was little known. Brooks, 36, was the eldest son of a moderately successful upcountry South Carolina planter. Having served a term in the state Legislature, he volunteered to lead a company during the Mexican War, established himself as a sometime-lawyer, sometime-planter, and in 1853 won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Described by a fellow South Carolinian as “tall and commanding, standing six feet in his stockings … [and] remarkably handsome,” Brooks had thus far made few waves in Washington. He was a moderate in politics, at least by South Carolina standards. He was charming—a nice man, by all accounts, the kind you might enjoy meeting but would promptly forget about.5 He had bright, piercing eyes, and flowing brown hair swept back from his forehead, his earlobes barely protruding. He cultivated a flourishing goatee that started toward the bottom of his chin, stretched wide across his jaw, and was just a little too long to be neat. In an 1850s photograph, Brooks projected pride, determination, ambition. He bristled at Sumner’s attacks, like all southern congressmen did. But for Brooks, the attacks were personal; Senator Butler was his father’s cousin.

Brooks believed he had no choice but to act, that Sumner’s incendiary language demanded a physical response.

The question was, what kind of response? Dueling was a well-worn means of vengeance in Brooks’ world. Indeed, he had already been involved in a duel and other “affairs of honor.” But he did not challenge Sumner to a duel, knowing full well that Sumner would refuse the challenge; dueling remained popular among wealthy white southerners but not so much in Massachusetts, and especially not in Sumner’s circle of pacifists and social reform activists. More importantly, duels were meant to be fought between social equals. Brooks most certainly did not regard Sumner as a social equal, and so he did not seek a duel. Instead, he resolved to inflict dramatic corporal punishment.

On Wednesday, May 21, the day after the speech concluded, Brooks lurked on the Capitol grounds, waiting to intercept Sumner, who did not appear. That night, Brooks accompanied two of his closest friends in the House, South Carolina’s Laurence Keitt and Virginia’s Henry Alonzo Edmundson, to Gautier’s, a well-known Washington restaurant, in the hopes of encountering Sumner—and perhaps administering the punishment there. But Sumner was not to be seen. Brooks hardly slept that night. It’s easy to imagine his friends urging him on, offering their support, ratcheting up the pressure to do something. By some accounts Brooks was drinking too much—presumably trying to relieve his tension but surely compounding it instead.

The following morning, Thursday, May 22, Brooks waited again, taking up a position in the porter’s lodge at the western edge of the Capitol grounds, looking down Pennsylvania Avenue, hoping to see Sumner arriving and intercept him before he reached the Senate chamber. Again, Sumner did not appear. Eventually Brooks gave up and went into the Capitol.

The House met only briefly that day, from noon until 12:30, adjourning early out of respect for a Missouri representative who had recently died. It must have been a relief for the restless Brooks to learn that the Senate would also adjourn early, for the same reason. He went to the Senate chamber and stood at the back of the room, just a few seats away from Sumner. More waiting. Finally, at around 1 p.m., the Senate adjourned.

But Brooks had to wait a little longer. He watched as Sumner sat at his desk, preparing copies of his speech—that speech, “The Crime Against Kansas”—to mail out to supporters. He waited between 15 and 30 minutes, though it probably seemed longer. Brooks felt he couldn’t confront Sumner because there were ladies present and what he meant to do was appropriate for a male audience only.

As was true for most of the bystanders, the first inkling of the attack came not through Sumner’s eyes but through his ears. “I was not aware of his presence until I heard my name pronounced,” he later recalled.

As I looked up, with pen in hand, I saw a tall man, whose countenance was not familiar, standing directly over me, and at the same moment, caught these words: “I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine—.” While those words were still passing from his lips, he commenced a succession of blows with a heavy cane.6

National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GalleryPreston Brooks (left) struck Charles Sumner (right) about 30 times in his assault, inflicting significant head wounds and rendering him briefly unconscious. After the assault on Sumner, many friends of Brooks believed further violence was inevitable. “If the northern men had stood up,” one wrote, “the city would now float with blood. The fact is the feeling is wild and fierce.”

According to Brooks, “at the concluding words I struck him with my cane and gave him about 30 first rate stripes with a gutta percha cane.” Brooks was confident that “every lick went where I intended. For about the first five or six licks he offered to make fight but I plied him so rapidly that he did not touch me. Towards the last he bellowed like a calf.”7

Some observers described Sumner as trying to resist, “clutching at the cane or at Mr. Brooks,” “defending himself from his blows,” or “striving to grasp Mr. Brooks.” But it was exceedingly difficult for Sumner to rise, trapped as he was beneath his desk. Senate desks were screwed to the floor to keep them in place, and the chairs were on rollers that required the user to slide back before standing up. Eventually Sumner wrenched the desk free from its fastenings, it toppled over, and he was able to lurch forward. With the desk overturned, however, Brooks had more room to maneuver and the ability to land more forceful blows. It was then that the cane began to break into pieces. In the confusion, a second desk next to the chamber’s central aisle was toppled, in front of and to the left of Sumner’s. Following a few more strikes, Sumner fell to the ground in the aisle, briefly unconscious and with several significant head wounds, two of them down to the bone.8

When Brooks’ friend Keitt wrote to his fiancee about the caning, he revealed the likelihood of further violence. “If the northern men had stood up,” he wrote, “the city would now float with blood. The fact is the feeling is wild and fierce.” Such a charged atmosphere would make it difficult to avoid additional fights. “Everybody here feels as if we are upon a volcano,” Keitt continued, hinting at the catharsis he suggested only violence could provide. “I am glad of it, for I am tired of stagnation.”9

Library of Congress

Library of CongressLaurence Keitt (left) and James L. Orr

The “sharp crack” that sliced through the normal soundscape of the Senate that day not only signaled an appalling assault on Senator Charles Sumner. It also heralded a new phase of the nation’s political conflict over slavery. As so often happens, violence spawned further violence. More immediately, though, the caning unleashed volley after volley of rhetoric—words justifying the violent act, words decrying it, words trying to make sense of what it really meant that one man had beaten another man unconscious in the Senate chamber. After May 22, 1856, aggressive language and aggressive behavior would spiral together with new intensity, driving the political polarization that ultimately led to civil war.

Most white southerners and the supporters of slavery lauded Brooks for inflicting a just punishment on an enemy who had gone too far in criticizing the South. Across the South, in private letters as well as newspaper columns, expressions of approval rang out. Brooks also received “rewards”: commemorative silver goblets, pitchers, and a large number of replacement canes. A public meeting at Clinton, South Carolina, praised Brooks for “using arguments stronger than words,” and presented him with a cane marked “Use knock down arguments.” Supporters rallied around the catchphrase “hit him again.” Although some southerners quietly bemoaned the caning, particularly the fact that it had taken place in the revered space of the Senate, these voices were drowned out by enthusiastic cheerleading, often tinged with support for more violence in the future.10

On the other end of the spectrum, African Americans and many white northerners were appalled, seeing Brooks’ act as an unjustified—and dishonorable—surprise attack. “To take a man at a disadvantage is as dastardly, as to attack a child or a woman,” commented The New-York Observer. “There is no courage, no chivalry, no manliness in such a deed.” This was more than an attack on the body of Charles Sumner. It was an attack on free speech—an attack on the principle that senators and congressmen, in particular, ought to be able to express themselves freely in debate without fear of physical reprisal. The best-known lithographic depictions of the caning published in the wake of the incident make this point powerfully. In John Magee’s “Southern Chivalry,” Brooks brandishes a stout stick (thicker than the real-life cane) while Sumner holds a pen in one hand and rolled-up papers in another. In Winslow Homer’s “Arguments of the Chivalry,” Sumner holds a pen, an apparently feeble defense against Brooks’ cane, and the image’s caption includes “the symbol of the North is the pen; the symbol of the South is the bludgeon.” Words against violence, free speech against slaveholder tyranny—this is what the caning boiled down to in northern eyes.11

Brooks “was but the agent of the Slave Power: all the South will justify his deed,” declared one Boston minister. In recent years northerners had become increasingly resentful of slaveholders’ grip on political power. To them, violence in Kansas and Congress indicated a troubling escalation of attempted Slave Power domination. As The New York Times put it, “The logic of the plantation, brute violence and might, has at last risen where it was inevitable it should rise to—the Senate of the United States.”12

In the eyes of many northern commentators, a line had been crossed and it was now time to actively resist the tyranny of the Slave Power. “In short, violence is the order of the day,” concluded the New York Evening Post. “[T]he North is to be pushed in the wall by it, and this plot will succeed, if the people of the free States are as apathetic as the slaveholders are insolent.” In other words, northerners must fight back. An Ohio newspaper reached the same conclusion after reflecting on the pattern of slaveholder brutality from the Sumner caning to the proslavery “border ruffians” who assaulted their “Free-Soiler” opponents in Kansas. Either the free states must submit “or else violence must be met by violence; blow given back for blow, blood demanded for blood, and life for life.”13

Library of Congress

Library of Congress Reactions to Brooks’ assault on Sumner broke down largely along sectional lines, with southerners generally offering words of support and encouragement and northerners voicing outrage and disdain. Among the latter expressions was Winslow Homer’s lithographic depiction of the attack titled “Arguments of the Chivalry” (above).

There were more moderate voices in both regions, to be sure. Southerners in cities like Baltimore, Louisville, and St. Louis were less likely to support Brooks. Their most frequent complaint was not that the attack should not have occurred, but that it should not have taken place in the Senate. In the North, newspapers affiliated with the Democratic Party blamed Sumner’s intemperate language as much as Brooks’ thirst for revenge for what had happened. Yet for the most part the caning drove the wedge of North-South division deeper, separating a growing number of Americans into those who believed abolitionist words justified proslavery violence and those who did not.

Some commentators rued the political purposes to which extremists were putting the caning. In North Carolina, the Fayetteville Observer was alarmed by the escalating dynamic of polarization, lamenting how Brooks’ attack had galvanized northern indignation, which in turn motivated southerners to circle their wagons around Brooks. A Tennessee newspaper disapproved of both Sumner’s speech and Brooks’ response—and the way partisans of both men were now agitating around the event. Particularly maddening were northern newspaper editors “making most precious asses of themselves” as they gave “a sectional and political character and importance to an outrage committed under passion, kindled by language toward an absent kinsman, such as had never before been heard in the Senate chamber.”14

In the weeks afterward, several northern newspapers reprinted selections of commentary on the caning from a variety of other publications. Reflecting their readers’ seeming appetite for sensational news, editors reprinted excerpts that illustrated each section at its most extreme. Abolitionist publications such as The Liberator and The National Era were clearly pleased to reproduce from southern newspapers “displays of Southern billingsgate, cowardice and ruffianism.” When The National Era printed a selection of excerpts from both northern and southern newspapers, it chose articles that were particularly extreme: a northern paper that advocated more violence in response to the caning, and several southern papers that not only approved of Brooks’ act but also called for additional violence where necessary. The editors involved surely recognized what they were doing in reprinting stories about violence that stimulated violence. The continuum of pugnacious words and acts would go on and on.15

The most significant political effect of the caning was to turn moderate northerners away from longstanding party alliances with their southern counterparts. Before the mid-1850s, America’s party system cut across regional lines, dampening the potential for North-South conflict; now, it mirrored and aggravated the regional divide. It happened that 1856 was a crucial election year and Brooks’ May 22 assault was perfectly timed to exacerbate the forces already upending national politics. The old party system of Democrats versus Whigs was breaking down, but it was not yet clear what new configuration would replace it. Provocative depictions of the man behind the cane, vilified as the embodiment of Slave Power aggression, galvanized support for the new Republican Party. During 1856, Republicans transitioned from minor players to a major political force, in part because they capitalized so effectively on the Sumner caning and the growing violence in Kansas, portraying themselves as the party of free speech in opposition to the vicious Slave Power.

Politicians on both sides of the divide recognized the power of the caning to inspire northern support for the new party and its presidential candidate, John C. Frémont. During the run-up to the election, Brooks’ fellow South Carolina congressman James L. Orr protested northerners’ use of the caning “to operate on the public mind in regard to the coming presidential election.” Noting that 100,000 additional copies of Charles Sumner’s speech were being printed for circulation, Orr called it “an electioneering document for the Republican party.” Years later, Republican politician Alexander K. McClure reflected on the crucial political turning point of 1856: “By great odds the most effective deliverance made by any man to advance the Republican party was made by the bludgeon of Preston S. Brooks.”16

Frémont’s opponent, Democrat James Buchanan, won the White House. Yet the election, thanks to the caning among other factors, was a consequential fork on the road to the Civil War. By cementing the upward trajectory of the Republican Party, 1856 pointed toward the election of a Republican candidate in 1860. And the fact that the new party’s appeal was largely confined to the northern states pointed toward an increased likelihood of political division sparking a regional conflict.

By the time the Republican Party prevailed in 1860, Preston Brooks was dead. Following his historic attack in May 1856, he came to an ironically pitiful end the next January, asphyxiating from a throat disease in a Washington hotel room.

After Brooks’ death, with national political tensions ever deepening, congressmen became more likely than ever to resort to violence. Historian Joanne Freeman has noted an increasing willingness among northern congressmen to fight back against southern oppression in the years after the caning. As one New Jersey newspaper noted, the caning reinforced an unfortunate tendency “to introduce violence as a means of political action and to intimidate into submission those who think fit to oppose certain public measures.” According to South Carolina Senator James Henry Hammond, in the late-1850s Congress “the only persons who do not have a revolver and a knife are those who have two revolvers.” During a House debate over the Lecompton Constitution—a proposed proslavery constitution for Kansas—in February 1858, Brooks’ South Carolina comrade Keitt came to blows with Pennsylvania Republican Galusha Grow. After Grow knocked Keitt down, Democrats and Republicans rushed in, instigating a general melee that involved some 30 combatants. Comedy helped defuse the fray when an opponent grabbed Mississippian William Barksdale by the hair—only for Barksdale’s toupee to fall off.17

The decade’s most spectacular act of violence took place in October 1859 in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The abolitionist John Brown and his comrades entered the town with the intention of stealing firearms from the federal armory there, weapons that could then be used to arm an uprising of enslaved people. The raid failed miserably, leaving 10 of Brown’s men and six civilians dead. Brown would be hanged for committing treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia—though not before cultivating a public image of himself as a noble martyr, using righteous violence to fight a holy war against slavery. Brown’s message resounded across the country, that violence was the only means capable of bringing an end to the sinful institution. His message was framed in large part as a necessary and proportionate response to the endemic violence of slavery: the everyday abuse of enslaved people, the brutality of proslavery settlers in Kansas, and the public violence of slaveholders embodied by Brooks. It was a message that echoed loudly among northerners in the coming years, perhaps most memorably in Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address in 1865—words that helped spur John Wilkes Booth to his own act of political violence.

It would be going too far to claim that Preston Brooks’ caning of Charles Sumner caused the Civil War. However, 170 years after that fateful afternoon, Brooks’ act looms large among incidents on the road to open sectional conflict. Brooks’ anger became one of the most powerful symbols of the Slave Power, which generated so much northern hostility against the South. In facilitating the rapid rise of the Republican Party in 1856, the caning helped set the stage for Republican success in the presidential election of 1860, which, of course, triggered secession and then war.

The caning also transformed the way Americans thought about the role of violence in the ongoing political fight over slavery. It was not the first offensive in the struggle. Violence was already underway in Kansas, in Washington, D.C., on plantations across the South, and in those parts of the country where abolitionists fought to free victims of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. Yet the caning stood out then, as it stands out now, as a watershed moment. An unprecedented incursion into the sacred space of the U.S. Senate, it sparked wide-ranging debate over the right to free speech versus the right to use force against it, and it evoked dangerous desires for further bloodshed on both sides of the conflict. In assaulting Sumner, Brooks shifted prevailing beliefs about what kinds of speech, and what kinds of actions, were conceivable in the fight over slavery. Violence begat violence. The ultimate results would unfold over four long years of war that ended with hundreds of thousands of Americans dead, 4 million African Americans freed—and a nation preserved through bloodshed.

Paul Quigley is James I. Robertson Jr. Associate Professor of Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech, where he also serves as director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies and director of the Center for Humanities. His latest book is The Man Behind the Cane: Preston Brooks, Political Violence, and the Road to the Civil War (Oxford University Press), on which this article is based.

Notes

1. U.S. Congress, House, Alleged Assault Upon Senator Sumner, 34th Cong., 1st Sess., 1856, H. Rep. 182, 36, 71, 39, 49, 47, 64.

2. Charles Dickens, American Notes, For General Circulation (1842; reprint, London, 1913), 87.

3. Charles Sumner, The Crime Against Kansas (New York, 1856), 2, 29, 3, 29.

4. 34th Cong., 1st sess., Appendix to the Congressional Globe, May 20, 1856, 544-547.

5. Charleston Courier, February 7, 1857, quoted in Robert Neil Mathis, “Preston Smith Brooks: The Man and His Image,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 79, no. 4 (October 1, 1978): 298.

6. Alleged Assault Upon Senator Sumner, 23.

7. Preston Brooks to John Hampden Brooks, May 23, 1856, Preston Brooks Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina.

8. Alleged Assault Upon Senator Sumner, 30, 32, 71.

9. Lawrence M. Keitt to Susanna Sparks, May 29, 1856, Lawrence M. Keitt Papers, Duke University Special Collections.

10. “Meeting in Anderson and Laurens District,” Edgefield Advertiser, June 4, 1856.

11. “Outrage and Cowardice,” New-York Observer and Chronicle, June 12, 1856.

12. Theodore Parker, A New Lesson for the Day: A Sermon Preached at the Music Hall, in Boston, on Sunday, May 25, 1856 (Boston, 1856), 38

13. Evening Post quoted in the Boston Daily Atlas, May 27, 1856; “The Signs of the Times,” Western Reserve Chronicle, May 28, 1856.

14. “The Brooks Assault on Sumner,” Fayetteville Observer, June 9, 1856; “Sumner and Brooks,” Athens Post, June 6, 1856.

15. “But One Issue—The Dissolution of the Union,” The Liberator, June 27, 1856; The National Era, June 5, 1856.

16. Rocky Mountain Song Book, Prepared for the Use of the Fremont Flying Artillery of Providence (Providence, 1856); Speech of James L. Orr, July 9, 1856, Appendix to the Congressional Globe: Containing Speeches and Important State Papers, etc., of the First Session, Thirty-Fourth Congress (Washington, D.C, 1856), 805-806; McClure quoted in William E. Gienapp, “The Crime Against Sumner: The Caning of Charles Sumner and the Rise of the Republican Party,” Civil War History 25, no. 3 (1979): 245.

17. Hammon quoted in Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York, 2005), 776; Joanne B. Freeman, The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War (New York, 2018), 230-243; “Sumner Meeting in Jersey City,” New York Herald, June 6, 1856.